This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

“I think your ideas come from outer space,” Nabatiyeh Governor told the group of women who came from the village of Arabsalim to visit his office in 1995. His words were punctuated by a smile all too familiar to many a woman, in many a situation; one that might seem friendly or consoling, while it is, in fact, a patronizing and cynical expression, as if saying: “Ladies, there is no need for tiring yourselves with suggestions. The men have enough “serious” work on their plates, and they know better what’s good for the community…” Although, these women’s “idea from outer space” was nothing more than a simple suggestion to put in place a mechanism for sorting waste from the source, recycling, and cleaning their village’s streets which have been littered due to the lack of an official body that held that responsibility at the time.

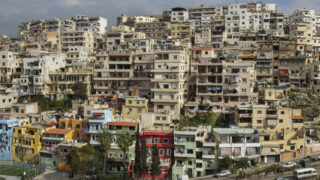

But, let us leave that scene for a while and travel forward in time. It is the year 2015, and a traveler in the Lebanese towns and cities, including the capital Beirut, might get the impression that the country has not yet left the trenches of the civil war, as its streets and alleyways look as though they belong to that era, with garbage piling up for no one to collect.

The “garbage crisis” of 2015 was caused mainly by the Nehme landfill overstepping its maximum capacity simultaneously with the only garbage collecting contractor company, Sukleen, halting all waste collecting activities. Meanwhile, at the height of that crisis, the village of Arabsalim was living on a different plane: waste-free, “clean as a whistle”, with its own active cycle of sorting, transporting, recycling and processing, which did not wait for government decisions, deals, or major companies and contractors (which, in a country like Lebanon, do nothing but pile up waste in unsanitary conditions, making garbage mountains, or otherwise burn waste in an environmentally hazardous and unhealthy manner; options which are catastrophic to both nature and man).

At the peak of that crisis, Lebanese media started to pay attention to the experience of that quiet little village in the south which was cleaned up by its own women who succeeded it shielding it from the mess that was every other street in the country. So, how did they do it?

The beginning

In the year 1995, the municipal council of Arabsalim, a village in the district of Iqlim al-Tuffah in South Lebanon, was dissolved. At the time, the Israeli army still occupied the southern border strip. Due to the prevalent instability and the absence of an official body that holds the responsibility of waste-collecting and keeping the streets clean, garbage started to pile up in the streets of the town, tarnishing the breathtaking scenery of the area which is surrounded by the majestic Rafei Mountain and crossed by small water creeks and a fresh water spring called “Kharkhar” (the gurgler) because of the flowing sounds of its heavy waters.

That was when one of the village’s women began to think that the state in which her hometown was living was unbearable, regardless of the overriding reasons and conditions. Zainab Mokalled, known by the townspeople as Umm Naser, was an Arabic language teacher who had always taken an interest in public service. She believed that the women of Arabsalim held the power to be game-changers through a simple, practical, inexpensive, and instantly workable solution. The magic words were “sorting from the source.” According to Umm Naser, it didn’t matter if the responsibility lies with the government or other state bodies, “government or not, it was unacceptable that the place we live in remain dirty. If no one will hold that responsibility, then we certainly should.”

And so, not a moment was wasted. Umm Naser shared her idea with her friends and the women of the village, and soon enough, a core team of 13 women was formed. They agreed to sort plastics, metals, and glass in their own homes and backyards, in different bags, separate from all organic waste. The purpose was to minimize as much as possible the volume of unprocessed waste. In parallel to their own work in sorting, they started a campaign to teach other families, especially the women, about the importance of waste sorting.

Khadija Farhat, one of the earliest members of the group, said in an interview with Assafir Al-Arabi: “At the time, we didn’t know what the phrase ‘organic waste’ meant. In fact, we weren’t familiar with many of the terms used in sorting and recycling. We only knew that it made sense to separate bottles, containers, and hard materials from everything that was foodstuffs or liquids that might cause odors. We sought to minimize the problem. At a later time, we learned the technical terms, methods, and other information related to our work.”

Suspicion and enthusiasm

“Do you think we live in Paris?” the women were told when they first started the project under the name “Arabsalim Women’s Association”. They were also told that their ideas were from “outer space”, unfitting for our society and country.

Today, 27 years after those modest and spontaneous beginnings, the group has grown to comprise 50 women instead of the 13 that started out, with more than 90 percent of the villagers contributing to the sorting from the source activity voluntarily and enthusiastically. The outcome says that such a project can indeed be “fit for a society like ours.”

With time, the “Association of Arabsalim’s Women” became a registered organization, under that name “Nidaa al-Ard” (“Call of the Land”); making the town of Arabsalim a unique example for serious, effective, and ongoing waste sorting in Lebanon, since 1995.

On a sunny spring day, Khadija Farhat, vice president of “Nidaa al-Ard”, recalls those early stages of their fieldwork. “Some people would call us “mannish”.

They’d say we were trying to take the place of the men, while many men thought we were trying to overshadow them based on the fact that we were taking lead of addressing a social responsibility without waiting for their permission. Some thought it was inappropriate that Umm Naser (Zainab Mokalled, president of the association), who had a distinguished social status as a school teacher, carry the broom and clean up the street. Mokalled has always been told that “this job was not for her,” while Khadija Farhat laughingly recalls how her mother sometimes reprimanded her for going out of her house onto the street to work in cleanup campaigns. Many associated collecting waste with menial jobs that do not receive appreciation, but Farhat stresses that the job of waste collecting is one of the noblest jobs; one that is indispensable to maintain healthy, agreeable living.

Lebanon: A Special Type of Rent

13-12-2020

However, the women learned to overcome these stereotypes, skepticisms, and discouragements, firstly by believing in the importance of what they do, and, secondly through the overwhelming support they received in the face of doubt. Farhat assures that the support of the townspeople far exceeded the criticism, which encouraged the women to go on. As their work began to take more organized forms, some women even started to express frustration from being “excluded” from the work cycle, and more people desired to be part of the project which gradually grew to cover the area of the entire village and beyond. “Had the people of our village not been cooperative, eager, and involved, we would not have been able to sustain the project’s continuity since 1995,” Farhat asserts, adding that Umm Naser has always said that her idea would not have come to anything had it not been for the women who had carried it on their own shoulders and put in the necessary efforts, and had it not been for the fact that the townspeople also embraced the project enthusiastically.

Awareness

However, how could a small community reach almost complete waste segregation within a few years, and how did the families of that community engage in a pioneering project that had no other local reference to imitate and that was neither known nor available to them before? The experience of “Nidaa al-Ard” is, hence, a really interesting one, because it's a model case that one can study to understand how a social intervention at this level can be sustained.

First, there had to be awareness efforts about waste sorting, recycling, and management. Farhat recounts how the ladies of Arabsalim devised a foolproof system to promote and advocate. They took every social event as an opportunity to meet with the townspeople, especially the women, to present the idea. “After each wedding, engagement, wake, or other familial or social event, we would kindly ask the attendees to give us 15 minutes or so to talk about waste management and ask them to join the efforts,” Farhat explains.

Continuity

During the first three years (1995 to 1998), “Arabsalim Women’s Association” relied solely on auto financing and modest private resources and efforts. As the group grew bigger, the media was invited to cover some of the activities, especially during the extensive cleanup campaigns that the association led in the village and its neighboring hills.

Soon after, Umm Naser realized it was essential that the association becomes a registered body so that it gets the much needed funding to maintain and develop its activities, especially after the financial issue became an obstacle that inhibited the purchase of a minimum amount of materials related to sorting and packing the village’s waste production. Thus, the association obtained an official license under the name "Nidaa al-Ard Association" in 1998, and its journey as an organized institution began.

After its registration, “Nidaa al-Ard” was able to obtain its first funding from the United Nations, amounting to 28 thousand dollars. At the same time, the new Nabatiyeh governor - this time impressed by the efforts of the women - granted the association a small plot from the communal lands in Arabsalim to be used as a center for sorting, packing and transporting waste, while before that, the women used to keep segregated materials on their private lots and backyards until they disposed of them or sold them to recycling factories. This was a pivotal moment for the association in the process of developing and consolidating its work.

Khadija Farhat points to the spot where the sorting plant lies, then to a piece of rugged land adjacent to it. “You see; this space was just as rough as that one. We have prepared it ourselves to be more hospitable and suitable for work.” She confidently asks me as soon as I enter the sorting plant: “Do you detect any foul smells?” She knows for a fact that no unpleasant odors exist in the plant because of how successful they have been in sorting from the source. The village’s women have been sincere in this process; they know that plastic, metal and glassware should be discarded only after they have been cleaned from the remnants of organic food and drink, and they work efficiently in such a way that makes the waste piles no more than a collection of clean and harmless materials, ready for pressing and transport. There is one machine that presses plastic, and another that presses paper; both were donated to the association, and they are operated by a worker at the plant who has overseen these processes for years.

The small waste sorting plant is located close to Arabsalim’s Public School, in a quiet spot a few minutes from the town square. It is now a warehouse in which all segregated waste is compressed then packaged to be sent to recycling plants. A fence was erected around the lot before the ground was evened out, and the area remained an open-air space until the association could provide enough money to build the warehouse. Farhat says: "A friend of mine and I used to drive our cars house to house around the village to take the segregated bags to the lot. We did all the manual labor ourselves, until we hired a man on a daily wage to transport the bags, but one of us women had to go with him at first because the villagers didn’t know him well enough to allow him into their homes.”

Even though the association has secured several funds, about 70 percent of its work is still only supported by the voluntary efforts of the women who work in it.

The women don’t see this as a setback; on the contrary, they speak proudly of working within their own resources. "We are fully aware that there are municipalities and NGOs that simply cannot do what we’re doing without large budgets, yet we’ve been doing it for 27 years nonstop nevertheless. Taking our own reality as an example, we see that our government was unable to solve the waste problem, not even in the most urgent instances, neither in times of calm nor distress,” says Khadija Farhat.

Under Israeli occupation

It is important to note that the waste sorting initiative in Arabsalim came at a time when the Israeli occupation still took hold over large areas of South Lebanon. “Al-Hara al-Tahta" (the lower neighborhood) in Arabsalim was still under occupation in 1995, so the villagers migrated upwards towards the neighboring village of Jarjoua, to the point that about half of Arabsalim's people became residents of Jarjoua. Due to this overlap, Jarjoua’s residents also became interested in sorting solid waste from the source. Women, once again, took the lead, as Jarjoua segregated its waste until the year 2000 - the date of the liberation of southern Lebanon from the Israeli occupation. As municipal councils were reassembled after the liberation, Jarjoua’s municipality demanded that it become responsible for waste segregation within its municipal scope instead of the association, but despite this, about half of Jarjoua's residents chose to keep on relying on "Nidaa al-Ard" for managing their segregated waste.

The volunteers tell a story about one of the clean-up campaigns in the nineties, when the Israelis started bombing Arabsalim as the women were going about their work on the streets. A journalist from the Lebanese newspaper, Annahar, happened to be passing by, and the sight of the women busy with their brooms and waste bags caught his eye. He later wrote an article entitled “The women of Arabsalim clean up their village under the bombs,” and they became well-known for what they did. They also remember another incident that happened around the time they were preparing the lot as their sorting plant in 1998, while the Israeli observation post of Al-Addousieh stood overlooking them on a hill nearby. “We ignored them as we worked, but we could hear the soldiers constantly threatening, aiming their weapons at us, so that we would panic and leave.”

Influence and outcomes

Several villages around Arabsalim were intrigued by the experience. Groups came from Houmeen and Kfar Roummane to learn about waste segregation methods, and many made individual initiatives to bring their sorted waste bags from their villages to the association. Meanwhile, schools in the adjacent towns of Ein Qana, Kfar Joz and Nabatiyeh also collaborated with “Nidaa al-Ard”, teaching their students about the importance of waste segregation and bringing in their sorted bags to the plant, which now includes an appended lecture hall that hosts delegations and classes from other villages and schools. “We believe they choose to come to us because the absence of any official mechanisms for waste management has placed us at the forefront as the only entity in the region involved in such work,” says Farhat.

By the year 2000, and right after the liberation of South Lebanon and the reassembling of municipalities in the region, more than 90 percent of the townspeople had joined the initiative, sorting their waste from the source.

Today, Arabsalim lacks a municipal council again. It has been dissolved since 2016 due to disputes between its members who belonged to Amal Movement and Hezbollah. The village relies on the governor and the local bodies who are concerned with public affairs, be they individuals or associations. According to previous municipal statistics, the population of the town, which covers an area of about 8 square kilometers, is about 12,000 people, about 7,000 of whom are permanent residents. The town produces 6 tons of waste annually, about 80 percent of which is organic, and the rest (about 1.2 tons) is solid waste, 70 to 80 percent of which is completely sorted by “Nidaa al-Ard.”

The factories or organizations which buy or accept to take in these solid wastes are extremely limited in Lebanon, with recycling plants almost nonexistent. More than one plastic factory, for example, insist that the cost of purchasing raw materials is less than the cost of processing and recycling plastic. For this reason, most sorting is sold to factories or organizations outside Lebanon. Meanwhile, “Nidaa al-Ard” has found simpler partial solutions, such as encouraging reuse and making the segregated materials available to scrap dealers. Such solutions reflect these women’s mode of action, summarized by Khadija Farhat in two basic principles: applying the most efficient solutions with minimal financial resources, and sorting directly from the source instead of collecting waste to be segregated later – an experiment that proved unsuccessful in other towns, as it required additional, complicated steps which waste time and effort.

Self-reliance

“If we don’t help ourselves, no one will,” says one of the association’s Facebook posts. The women speak lovingly and respectfully of Umm Naser, today an 80-year-old lady who still actively pursues public service and remains passionate about the environmental project she had started. The women now know for a fact that they are capable not only of thinking up ideas and plans, but also of implementing their projects and making a real difference. They are each other’s support system, driven largely by their sincere love for their hometown, its nature and people.

Today, in these times of adversity, and in conjunction with the most violent economic crisis that Lebanon has ever witnessed, these women’s initiative emerges as one of the few bright spots in the dark, calling for contemplation of its processes on several levels: First, in terms of its relevance to local work within the framework of a peripheral and marginalized region. Second, because it is a genuine grassroots initiative that stems solely from the desire of the population to find solutions to a problem that directly affects them. Third, and just as important, being an all-women’s initiative reflects the influence and role of the town’s women residents in the field of social and environmental work and their ability to manage public affairs, and to do so successfully.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 26/04/2022