Nahla Chahal

Professor and researcher in political sociology

Editor in Chief, Assafir Al Arabi

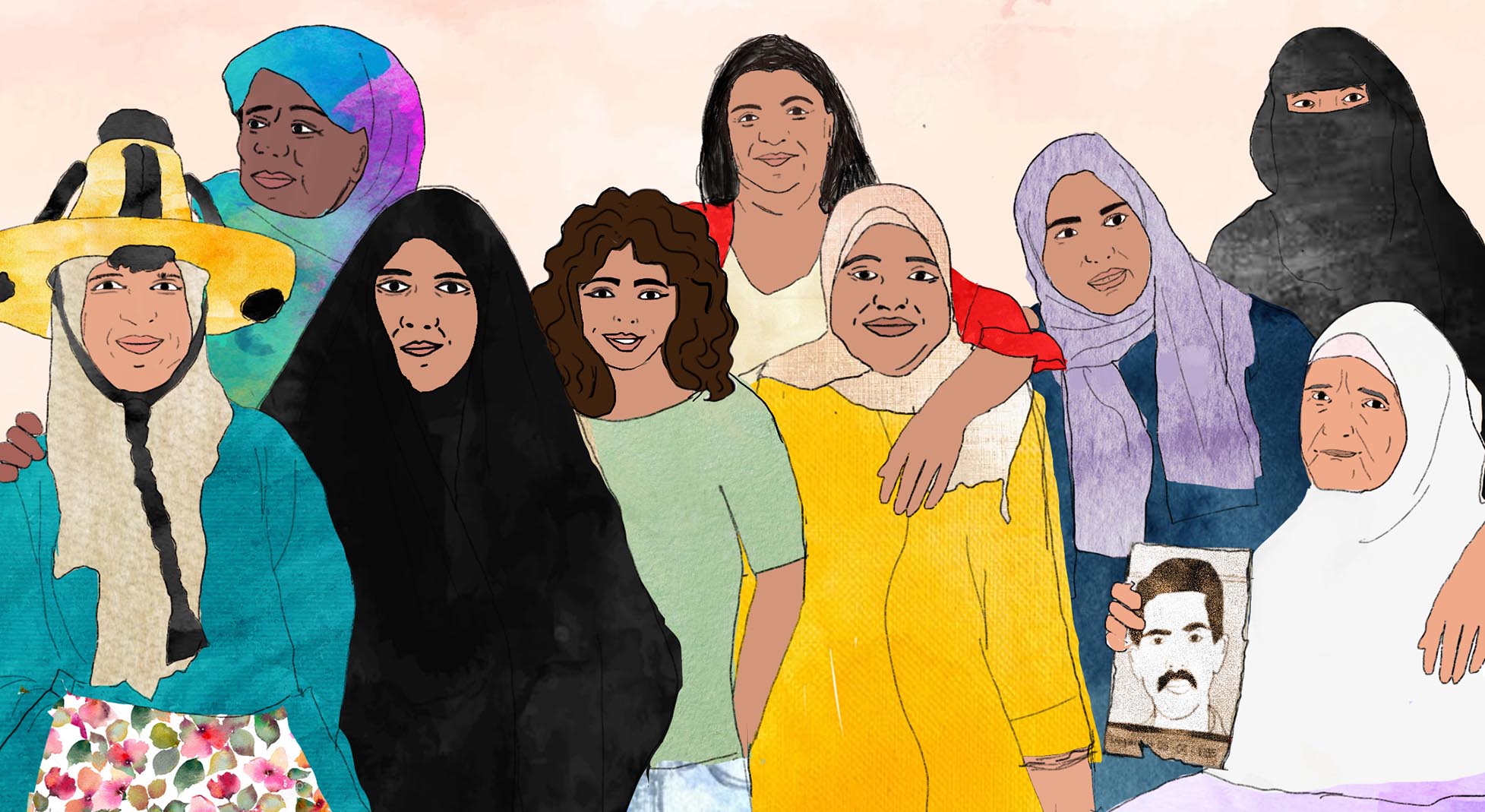

These texts trace the experiences of different women, in collectives big and small, in their attempt to take up social responsibility and perform social tasks – essential for daily life and long-neglected by the authorities, and even by society itself.

These texts do not claim to document every single experience nor can they, but they are presented as samples from eight countries that speak to the power of taking initiative, persistence, and diligence, as well as pride and joy. Proactivity is extremely important; it is the opposite of surrendering to the terrible state of affairs, and embodies a sense of public responsibility. The two traits, proactivity and a sense of public responsibility, are fought by the incumbent authorities with all their might. They choose to fight action out of laziness, foolishness, and the conviction that allowing things to go stagnant is what continues to enable them, that is, the authorities, to run the country and its people while avoiding “headaches”, fearing that such examples might awaken the people and could set a precedent for others seeking to develop similar projects. With these stories, we have aimed to introduce the projects that managed to make a difference for their initiators and their milieus, despite the frustrations, both personal and shared, lived on the ground.

This folder, with texts from Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, Egypt, Morocco, and Sudan, might help clarify the general state of affairs – with several realities suffocated by war, conflict, misery, neglect, and authorities which look down on their own people. Perhaps they might also help reach conclusions that would hopefully inspire other similar initiatives. We have listed here not only the successful and enduring projects, but also those that were obstructed and couldn’t go far beyond the serious attempts that they were, while discussing why they have failed or stumbled. Perhaps looking into all these, comprehensively and in their diversity, helps link them all, retaining them in a in collective “space”, alive and real. Furthermore, it allows for an exchange of ideas, experiences, and impact. Some of these initiatives are related to production, some to education, healthcare, and others to public services. Some were driven by intellectual and social common convictions, while others may have been related to specific individual conditions. Either way, each of these experiences is extremely meaningful.

Otherwise, the experiences told here were not carried out by women from elite classes; none of these initiatives were decreed from above but rather motivated by meeting needs on the ground.

Why observe women’s movements in specific? Because women have been kept in the margins and assumed to have no interest but in their own space, namely the family. And while of course, they do assume great responsibility over this space said to be their “realm”, such a division of labour is neither accurate nor truthful. It never has been so. Believing in this assumed division has now become, however, a disgrace, in the literal sense of the word. Women have been active in the public sphere throughout history, and have always been productive members of society, even if only within the confines of their families and the rules set by those families. As for today, and even though all this has been denied, whether conceptually, legally, or socially, these lines/ limits have already been crossed! What we mean here is the material reality related to pursuing education, joining the production fronts, and the ability to play crucial social roles that might have been neglected – whether because they were considered to be a “luxury” or due to thinking that handling them or transforming the current state of affairs would be a difficult undertaking.

These texts then try to document exactly that: how young women from Yemen decided to mediate between warring parties in order to facilitate prisoner exchanges, mobility, and even water sharing; how women, now aged, have insisted on figuring out their children’s, brothers’, and husbands’ fate, forcedly disappeared in Algeria; how children with physical and mental health issues in a destroyed Iraq are being rehabilitated; how revenues were made from whatever little was available rather than giving in to destitution in Morocco; how a minimum level of security was guaranteed despite penury following rough times in Egypt, Sudan, and elsewhere; how women refused to adapt to the tremendous build-up of garbage in one of Lebanon’s villages, rather deciding to safeguard and enjoy their beautiful and clean environment; how a woman has managed to become Mayor in Upper Egypt, and how Egyptian Christian women are fighting for their right to divorce. Premised on these examples and others, this “new” reality is traced: if oppressed and outcast women have proven themselves to be capable and proactive, why doesn’t everyone else do so as well, be they man or woman?

The research and investigative team that wrote these texts is in itself made up of women writers, journalists, and researchers. They’ve determined the general framework through which the situation of women in our countries would be discussed. In one of Assafir Al-Arabi’s folders, titled “Disparity: The Status of Women between 2 Prevalent Beliefs and Reality”, they try to highlight the discrepancies between what is commonly believed to be women’s status, ranking them as “secondary citizens” and incapable, and the realities of their work on the ground, which prove that women are in fact capable, responsible, and aware. This current folder, which addresses women’s initiatives who stand up for society’s needs and their own, will be followed by a third that addresses the process of the big battles that they’ve been fighting for a while to change some entrenched practices. These include female genital mutilation, child marriages, every type of violence that women face, violating their integrity with harassment and contempt, and depriving them of their rights, whether to inheritance, the lands they farm, agency, or to the custody of their children… How far have these battles gone? What have they achieved? What have they managed to consolidate? Which course has each taken? And what further issues need to be addressed?

Yemen

Sudan

Algeria

In Algeria: No News and No Tombs

09-07-2022

Iraq

The Lifemakers of Iraq

21-10-2022

Egypt

Lebanon

Morocco

In Morocco: Women Draw Light out of Darkness

06-07-2022