This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

He called me by my name, preceded by the title “Miss”. I looked over my shoulder to find Salah, a boy I had taught eight years ago at a summer camp in one of the public schools in Bab el-Ramel, an extremely impoverished area in Lebanon’s Tripoli. However, I instantly recognized him - the smile that exposed a messy row of teeth and the unmistakable, slender form and posture which made it easier for his teacher at the public school to pull him out of his chair by the ear as a form of punishment. While I've forgotten the details of the punishment, I haven't forgotten that teacher’s “creative” violent ways. The Shisha Salah was carrying caught my eye. He told me that he had dropped out of school and was now working in Shisha delivery.

My mind was inundated with the memory of that first day of school. The kids always came into the playground overdressed. The boys looked like little men with their collared shirts and leather shoes, and the girls donned their prettiest dresses, probably the same ones they wore last Eid. I turned my back on the memory of that “Eid”, and my eyes welled up with tears.

During my teaching experience, I also met Amal, a nine-year-old girl who studied at an educational center in Bab al-Tabbaneh, the poorest area in Lebanon. When I asked the students to read an Arabic text, Amal said, “We have to memorize the text so we can read it.”

Amal and her peers had been part of the “automatic promotion” of the students of the first, second, and third grades, which was introduced in 1998, when the “new curriculum” was installed. These students suffer from “educational poverty,” which means that most of them reach the age of ten while still unable to read simple texts. Although the Minister of Education revoked this measure in 2010, following a 13-year-long experiment, the outcome was a generation that struggled with the basics of literacy.

This is just one example of the decline in the quality of education, and just one example of school dropouts, as precursors to the years leading up to the autumn of 2019, which marks the commencement of the “Lebanese crisis”. In public discourse, the crisis is set on a backdrop of a crumbling educational system, particularly in public education, where the slogan “4 years to compensate” was adopted due to the prevalence of “learning loss[1]”.

The gradual but expected educational decline is the result of the accumulation of relevant quantitative and qualitative shifts spanning nearly 25 years. The causes, indicators, and consequences of this decline were further accelerated by the onset of the Lebanese crisis, culminating in what can be aptly described as a collision. The crisis became the default justification; a scapegoat to blame for the educational crumble. The official Lebanese rhetoric has contented itself with using the crisis to downplay the problem, avoid analyzing its root causes, and consequently, shirk its responsibilities in implementing measures to save the educational sector.

Salaries and teacher structures

The debate around teachers’ salaries in public education has raged to the point of burning out. The core problem which concerns the teachers, the backbone of education, has become increasingly impenetrable.

The latest measure in this regard was announced by the Ministry of Education in the academic year 2023-2024, amending salaries to seven-fold their value. This increase, however, is in vain, due to the sharp devaluation of the Lebanese lira by 90%. A teacher’s monthly salary is now equal to no more than $140, which teachers rarely receive on time. As such, the public school year formally commenced October 9, 2023, with teachers who have lost hope in receiving their salaries, following extensive strikes at public schools for a total of three months during the previous year 2022-2023. The strikes had many reasons, the most important of which were delayed and meager salaries and broken promises about financial incentives. Due to divisions between educational leagues, resuming regular education became dependent on the independent decisions of teachers.

“Automatic promotion” was introduced in 1998, when the “new curriculum” was installed. Promoted students suffer from a case of “educational poverty,” which means that most of them reach the age of ten while still facing difficulties reading and writing simple texts.

In its 2022 report, UNICEF stated that “3 out of every 10 young men and women in Lebanon have stopped their education,” and that school enrollment declined to 43% in the same year. Despite hosting about half of Lebanon's population, Beirut notably has the lowest percentage of public schools at just 5.82%.

Public teachers’ complaints and their questioning of the integrity of the Ministry of Education erupted after it became clear that in the year 2022 alone, UNICEF and the World Bank had provided $64 million in emergency aid aimed at teachers, of which the latter received only a small portion. The teachers have been demanding an answer – to no avail – as to why they had been receiving their salaries in Lebanese liras when the Ministry receives the money from donors in US dollars.

However, the financial problem was triggered by a structural dysfunction within the educational staff, due to a surplus of contract-based teachers, many of whom had been hired by virtue of political clientelism. This door was opened wide after the new curricula were introduced in 1998, under the pretext of the need for new teachers for civic education, technology, and arts. The Ministry of Education went on to hire 9,300 contractual teachers. These employments are based on a fad of “special contracting” that originated in the 1960s, a period that some consider the beginning of the decline of public education. Contracts continued despite the issuance of Law No. 442/2002, which specifies the procedures for employment in the educational body and for competitive examinations for contractual teachers to promote qualified candidates to the permanent public staff. These examinations, however, were never held.

Contract teachers are not subject to administrative oversight and do not enjoy the minimum level of job stability. This has been reflected in the steady decline in the level of public education.

Distance learning

Public students endured a significant setback, losing a year and a half (during the Covid-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2021) due to home quarantine and the adoption of “distance learning”, an approach that has proven to be largely ineffective among students in the context of public schools.

Since 2010, Lebanon has received a cumulative total of about $2.5 billion. According to World Bank estimates, the construction of a school costs approximately $2 million, school expansions around $235,000, and restorations range between $300,000 and $700,000. These figures mean that the funds received by Lebanon could have easily built over 100 schools, expanded 200 others, and restored the entirety of Lebanon's school facilities.

According to an educational expert[2], parents tended to direct their attention toward older students and those who were applying for official exams (the Lebanese Brevet and Baccalaureate). Consequently, these students were given preference in accessing educational resources such as cell phones or laptops, assuming the latter was available, and if and when electricity was available, as recurrent power cuts have become commonplace unless residents resort to costly private generators. Even when these means were available, there remained the risk of internet disconnection, leaving a substantial majority of public students without access to a proper, regular, and serious education.

At the level of virtual education skills, the expert highlights a concerning lack of commitment among public teachers to the training courses organized by the Teachers' College. A mere 25% of teachers engaged in “Teams” virtual platform, with the majority opting for a more lenient approach by delivering lessons via WhatsApp. This deficiency in embracing modern education techniques persisted even during in-person educational sessions, particularly among older professors. Reason for this continued deficiency include the absence of proper oversight and the shortage of coordinators responsible for supervising curricula and evaluating teacher performance.

Mapping education

As a result of the economic crisis, about 55,000 students moved from private schools to public schools in Lebanon in the academic year 2020-2021 alone, which has increased pressure on public schools, according to a World Bank report (2021).

There are no accurate statistics on school dropout rates in Lebanon. The 50% rate announced by Save the Children in one of its video reports, published in September 2022, includes Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian students. What is clear from this percentage is that there is an evident increase in dropouts during the crisis-riddled years. In its 2022 report, UNICEF stated that “3 out of every 10 young men and women in Lebanon have stopped their education,” and that school enrollment declined to 43% in 2022, while no statistics were published regarding the school year 2022-2023. The general impression notably reflects wide adaptation to the economic crisis, and consequently implies an increase in school enrollment in 2023-2024, simultaneously with a maintained status quo of comprehensive dollarization of the Lebanese economy, with the relative stability of the lira exchange rate.

However, despite severe poverty, only 31.34% of Lebanon’s students are enrolled in public education, while 52.93% study at private institutions[3], which indicates that the Lebanese have remained reluctant to trust public school systems and have preferred private education despite their added financial burdens.

These 336,301 students are distributed among the educational levels as follows:

Kindergarten: 51,907 students

Primary basic education: 148,717 students

Intermediate basic education: 69,741 students

Secondary education: 65,936 students

With 1,232 primary and secondary schools, public education is considered the most widespread in Lebanon, constituting 44.28% of the all schools.

The disintegration of Lebanese University salaries further compounds the crisis, exacerbating the exodus of educational staff, with around 600 full-time professors leaving their positions in the academic years 2022-2023 and 2022-2021. Most of those professors teach scientific subjects such as engineering, mathematics, and informatics. Numerous faculties, including medicine, health, and media, have announced several vacancies in bachelor's and master's programs.

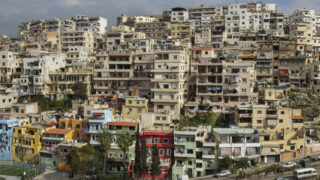

The distribution of public schools in Lebanon is notably concentrated in marginalized and peripheral governorates. The southern suburbs of Beirut take the lead, accounting for 16.89%, closely followed by North Lebanon at 15.06%, then rural Mount Lebanon at 13.26%, Akkar at 11.18%, South Lebanon at 10.78%, and the Bekaa region at 9.35%, while Nabatieh’s and Baalbek-Hermel’s shares are at 8.95% and 8.7% respectively. Strikingly, Beirut, despite hosting about half of Lebanon's population, has the lowest percentage of public schools at just 5.82%.

These figures exclude vocational and technical education, which operates within its own, predominantly public, institutions, and is influenced by cultural considerations which perceive this form of education as the “least favorable”, reserved for academically challenges or failed students. The outlook for vocational and technical education in Lebanon has not evolved much, and the sector shares some challenges with public education, especially concerning contractual teachers. Furthermore, this sector's growth has matched neither the demands of the market for technical skills nor the preferences of industrialized countries like Germany and Canada that actively seek economic immigrants with vocational degrees. In Lebanon, the combined enrollment in the BP, BT, and TS stages (the respective equivalents to intermediate, secondary, and university academic education) amounts to no more than 40 thousand students.

Syrian refugees

The Syrian refugee crisis has frequently been subjected to vague and populist diagnoses. Education has been at the forefront of these issues, with Syrian refugees unfairly shouldering the blame and responsibility for depriving underprivileged Lebanese students of educational opportunities.

However, according to educational researcher Neamah Neamah, since the onset of the war in Syria in 2011, successive Lebanese governments have perpetuated a misconception that international aid is exclusively directed toward educating Syrian refugees. In truth, during the peak of the refugee crisis, the number of refugee students did not surpass 210,000, and today, fewer than 100,000 are enrolled in evening school hours, while 342,304 Lebanese students are registered for the academic year 2022-2023, as reported by Information International.

Neamah says that the Ministry of Education has been implementing multiple projects funded by various donors since 2011, including initiatives such as Race 1 and Race 2[4]. These projects are not solely geared towards educating Syrian refugees; instead, they benefit the entire public education sector in Lebanon.

Neamah makes a financial comparison, arguing that since 2010[5], Lebanon has received a cumulative total of about $2.5 billion from international organizations to support public education, of which the funds allocated specifically to the education of Syrian refugees amount to an estimated $600 million. The remaining funds have been directed towards developing curricula and bolstering the infrastructure of public schools.

Collapsing to death

In 2022, Lebanon's educational body was shaken by the tragic death of 16-year-old student Maggie Hammoud at the American Street Public School in Tripoli's Al-Qubba, when the ceiling of her classroom collapsed onto her. The calamity triggered a series of inquiries into the Ministry of Education's commitment to school inspections prior to opening them for students, sparking discussions about the allocation and utilization of funds for public school infrastructure projects.

After the incident, the Ministry of Education adopted a closed-door policy, refusing to entertain questions from journalists and researchers. This stance only deepened suspicions regarding the ministry's awareness of its negligence (at least). Upon scrutiny of international reports, it was revealed that the Ministry of Education had received loans and donations totaling $200 million[6], which were supposed to be disbursed between 2014 and 2022.

According to World Bank estimates, the construction of a school costs approximately $2 million, school expansions around $235,000, and restorations range between $300,000 and $700,000. These figures mean that the funds received by Lebanon could have easily built over 100 schools, expanded 200 others, and restored the entirety of Lebanon's school facilities. Yet, distressingly, school ceilings continue to collapse on students.

While the collapse of a school ceiling results in immediate indignation at the human tragedy, the news tend to fade from public discussion within a few days. However, there are ongoing infrastructural deficiencies that create daily suffering, particularly in schools located in villages and suburbs. These institutions grapple with challenges such as the absence of heating in winter, inadequate ventilation and cooling systems, lack of sanitation networks, and frequent power outages. A particular photograph depicting a darkened classroom in a northern public school during the winter of 2020 went viral on social media. The image showed candles as the only source of light in a classroom filled with attentive students. The Ministry of Education did not comment on the situation, as it was busy with the curriculum development process, despite only making marginal changes in the curricula since 1998.

Public university and schools: similarities and disparities

The initial attempts to instate public education in Lebanon date back to 1838. The original aim was to cultivate a proficient administrative apparatus, capable of facilitating administrative reform within the Ottoman Sultanate[7]. Approximately 150 years from the establishment of public schools, Lebanese government continues to grapple with administrative bankruptcy and lack of vision, coupled with lack of transparency, rampant corruption, and suspicions of corrupt conduct in public education management. What applies to public schools is almost exactly mirrored in the Lebanese University, a national institution founded in 1951. However, the outcomes of this performance in both institutions reveal some distinct differences.

The collapse of public education is profound and all-encompassing, sparing only a few schools that make independent efforts to uphold high standards. Evidence of their perseverance appears in the top ranks that their students score in the official examinations. Students, particularly in the southern villages and outskirts, stand out, and part of the matter may be attributed to their viewing education as a means to rise above challenging circumstances. These regions are often influenced by political parties that use education as a means for advancement on the social ladder and to counter a sectarian-based narrative that views these areas solely as centers of deprivation and oppression. It can be said that these partisan groups exert effective and robust control over these schools.

On the other hand, the Lebanese University maintains decent standards in degrees that remain highly desirable by prestigious universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. It is noteworthy that, according to the QS 2024[8], a key index of world academic reputation and performance, the Lebanese University globally ranked 364th in 2023, moving 74 points up from the previous year.

A full-time professor at the Faculty of Information and Mass Communication in the Lebanese University commented: “There are professors who consider the Lebanese University's survival as their own cause. They seek to prevent its complete collapse, while recognizing that the entire country is in a state of collapse and is thus unable to provide more”.

Public education is the bedrock for the entire educational sector in Lebanon. The deterioration of public schools has had a cascading effect on private schools. Between 2000 and 2010, the decline in the quality of public education led to the mushrooming of private schools which took advantage of the good reputation of established private institutions to establish contingent, “commercial” institutions of lower standards, which mainly attracted middle-class families.

Lebanon has approximately 48 private universities and institutes, a staggering number considering the country's size. However, only a handful adhere to international standards. The majority have capitalized on the Lebanese University’s many crises, where employment has become linked to sectarian quotas, as in much of the state’s institutions.

Here, a question can be posed regarding the sustainability of quality education at the Lebanese University, taking into consideration an array of challenges that directly impact professors, whose monthly salaries have devalued[9], plummeting to an alarming average of $150 only, with new full-time professors receiving a meager $100. In the heyday before 1983, most PhD holders pursued full-time teaching positions at the Lebanese University, which promised them an excellent monthly salary of around $3,000. That reality came to a dramatic end with the economic chaos following the withdrawal of the PLO from Lebanon, as the sizable budgets once deposited in local banks, daily nourishing the country’s economy, were abruptly terminated.

Lebanon: A Special Type of Rent

13-12-2020

The disintegration of Lebanese University pensions further compounds the crisis, exacerbating the exodus of educational staff, with around 600 full-time professors leaving their positions in the academic years 2022-2023 and 2022-2021. Most of those professors teach scientific subjects such as engineering, mathematics, and informatics. Moreover, numerous faculties, including medicine, health, and media, have announced several vacancies in bachelor's and master's programs.

Private education is a stakeholder

Present-day education in Lebanon is going through an era of rapid unravelling, leaving the future of academic institutions uncertain and raising concerns about their ability to uphold decent standards. This situation is exacerbated by the persistent absence of clear government policies, vision, and solutions. Instead, there is a reliance on external donors, together with a perpetual self-exemption from the necessary task of updating outdated curricula. These courses remain unchanged in avoidance to stirring political tensions, specifically in civic studies and history books, which remain trapped in the pre-independence era up to the 1943 independence.

Public education is without a doubt the bedrock for the entire educational sector in Lebanon. Therefore, the deterioration of public schools has had a cascading effect on private schools. Between 2000 and 2010, the decline in the quality of public education led to the mushrooming of private schools which took advantage of the good reputation of established private institutions to establish contingent, “commercial” institutions of lower standards, which mainly attracted middle-class families.

The sectarian dynamic in Lebanon, which was initially concerned with competing to create the best educational institutions, has become more concerned in narrow sectarian quotas which corrode education. This transformation is the result of an implicit agreement fostering joint corruption and gradually undermining the entire educational sector.

Lebanon has approximately 48 private universities and institutes, a staggering number considering the country's size. However, only a handful adhere to international standards, while the majority have capitalized on the Lebanese University’s many crises, where employment has become linked to sectarian quotas and nepotism, as in much of the state’s institutions. Meanwhile, the Lebanese University has regrettably become increasingly commercialized, catering to the interests of influential business and political forces.

The role of religious sects

The repercussions of the educational system’s decay extend beyond the realm of education itself and its quantifiable objectives. It has left damaging marks on a legacy of remarkable educational progressiveness. This status of educational privilege did not come easy to Lebanon, with the journey starting with the priests who had received an education in the Maronite School of Rome and returned to establish the first Maronite school[10] in Jubbet Bsharri in 1624. This marked the beginning of a steady trajectory of educational development, making education perhaps the only foundational institution in the country.

Understanding the current decaying state of education necessitates studying the trend of reactionary decline of religious pluralism in Lebanon. Religious sects had, initially, catalyzed the establishment of the first schools in Lebanon and the Arab region. They were spurred by global and local rivalries, especially among Lebanese sects and their leaders, who secured help from their foreign allies, such as France, Italy, the US, Britain, and Russia. Missionary expeditions successively entered the scene, including Catholic, Protestant, Capuchin, Jesuit, Azarite, and late Orthodox missions. This movement largely defined the 19th century in Lebanon, wherein these missions extended their influence to Syria and Palestine, inspiring the Lebanese to establish national missions of their own. In the wake of this educational leap, the modern Arab renaissance took shape. Some if its prominent pioneers sprung from Lebanon and contributed to a literary boom and thriving journalism and publishing sectors.

One cannot deny the significant role played by these institutions, rooted in missionary traditions, in honing French and English language skills, which have been part of the populace’s invaluable cultural capital. These establishments, alongside their secular counterparts, have produced top-grade graduates.

However, the sectarian dynamic in Lebanon, which was initially concerned with competing to create the best educational institutions, has become more concerned in narrow sectarian quotas which corrode education. This transformation is the result of an implicit agreement fostering joint corruption and gradually undermining the entire educational sector.

The question is, can we repair what is being dismantled by this collapse? There will be little light at the end of this tunnel as long as the educational sector remains under the patronage of a deeply entrenched, corrupt political system. In the forthcoming years, the true magnitude of the harm wrought by the breakdown in education is anticipated to surface across social, economic, cultural, and moral dimensions—not to mention its impact on scientific and economic levels. One is reminded by the vital lessons offered by Durkheim[11], pointing to the fact that a school is not merely a physical space or “location”; it is a “moral milieu” par excellence.

______________

*This is the first article of the folder “The Collapse of Public Education Compromises the Future”, with the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

______________________

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 25/11/2023

1- The term “learning loss” refers to the students’ loss of knowledge and skills they had been expected to attain during a given period in their academic progress. ↑

2- Judy Ateeq and Asmaa Hamwi, “Crises are disintegrating public education in Lebanon: Children without education,” Nidaa al-Watan newspaper, September 12, 2023. ↑

3- “Statistics Bulletin of 2021-2022”, Center for Educational Research and Development (CRDP), 2023. ↑

4- Iman Abed, “The phenomenon of learning loss is on the rise in Lebanon: Who bears responsibility for plunging students into the unknown?” Raseef22 website, May 12, 2023. ↑

5- Jana al-Dhaibi, “The reality of education in Lebanon is reeling under the impact of strikes, together with the collapse of the currency”, Al-Jazeera website, February 4, 2023. ↑

6- Faten al-Hajj, “School Restoration: How was the $200 million spent?” Al-Akhbar newspaper, December 29, 2022. ↑

7- Christine Awad, “Lebanon and what it offers in educational system development (Part Seven)”, Ahram Canada website, June 14, 2019. ↑

8- Shadi Khawandi, “University Rankings: AUB advances... and Lebanese University excels despite neglect,” Al-Modon newspaper, July 3, 2023. ↑

9- Batoul Bazzi, “The “catastrophic” salaries of Lebanese University professors... emigrations, resignations, or working for only $150”, Annahar newspaper, March 29, 2023. ↑

10- “Education in Lebanon and the Levant”, Episode of “Bells of the Levant” program, “Al-Mayadeen” TV Channel, December 14, 2019. ↑

11- Marcel Fournier, “Emile Durkheim (1858-1917),” translated by Fatima Zahraa Arzawil, Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 2021, p. 998. ↑