This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Talking about climate change in Lebanon seems almost idealistic when the country’s reality lacks the implementation of any measure whatsoever. To take a recent example, when Lebanon declared on the 10th of November 2022, during the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh, that it has adopted the initiative for “fighting climate change,” the Ministry of Public Health in Lebanon was recording 3160 cholera cases and 18 deaths. UNICEF stated that it has repeatedly warned (1) that “the water infrastructure in Lebanon is on the brink of collapse,” and that “the crisis has not been resolved, and millions of people are affected by the limited availability of clean and safe water.”

Cholera is but one of the manifestations of the faltering water supply and sewage networks in Lebanon. It reflects the unpreparedness of the country to confront one of the consequences of climate change, represented by the increase in the intensity of precipitation. The scarce rain, which falls heavily in short time intervals, overburdens the sewage networks that are already worn out, flooding the streets and carrying to groundwater the sediments of gas stations and synthetic lubricants, in addition to the organic remains and untreated medical and industrial waste.

Meanwhile, the Water Sector Recovery Plan, which has been fervently discussed since the middle of this year, 2022, has now disappeared. This plan cost the state $9 billion, 2 billion of which were allocated for conducting studies. “Had we wanted to discover water on Mars, it would not have cost as much,” one expert sarcastically commented.

Climate Change: It’s About Time!

29-12-2022

Lebanon: Temperature Rises and Risks Multiply

24-11-2022

Waste, shortsightedness, and the lack of preventive policies are not limited to climate change; those are the main characteristics inherent to all Lebanese public policies, even when plans are devised and laws are enacted. This situation has branded Lebanon a “failed state” that has fallen into “the traps of governance.” Policies are subject to the consensus of the sectarian leaders who come up with solutions that solve nothing except how to divide the profits among themselves. This is how Lebanon deals with the climate crisis through abandonment, escaping forward, and a process of exclusion that disrupts the mechanisms of accountability and hinders any effort to evade crises or even contain them when they occur. In this context, reforms, if any (and they are always a formality), are incented by external forces, as they threaten Lebanon by depriving it of international loans and grants.

There is overwhelming proof of Lebanon’s shortcomings in dealing with climate change, which also affects issues of waste, electricity, and forest wealth. It is known that CO2 is one of the most important greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming and consequently climate change. It is a gas that is emitted abundantly from solid waste, forest fires, and the burning of fossil fuels, which Lebanon has not replaced with clean energy to generate electricity. These challenges are exacerbated by the absence of an efficient and effective management of the pressing issues, noted everywhere from the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environment to the Beirut Port explosion that unveiled the reality of a decaying state. The government did nothing to address the air toxicity that resulted from the explosion but, to begin with, it had demonstrated unimaginable neglect when it allowed the storage of enormous quantities of Ammonium Nitrate without any precautions, and without making any real effort to contain the consequences in the aftermath of the tragedy.

A powerless executive power

There is a structural defect in the management of climate change represented by the limited jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environment, with the loss of powers within several institutional and productive sectors, an unproductive bureaucracy, loose legislation, and a meager budget (not exceeding 400 thousand US dollars). As a result, the Ministry of Environment has become more of an advisory committee than an executive power, rendered incapable of managing the crises of climate change.

In 2002, Lebanon took the overdue step of enacting the “Environmental Protection Act” No. 444 as a comprehensive legislation concerned with various sectors such as industry, transport, energy, and other sectors related to human activities like water, soil, and biological diversity. The law set general principles to protect the environment, all of which are associated with climate change. However, the act would not be effective unless its implementation decrees are set forth. This is taking place at an excruciatingly slow pace. Twelve years later, the government has issued only 4 out of 20 implementation decrees, which makes this legislation a “symbolic law" that the authorities have enacted to keep up with the international environmental policies without taking any serious steps to make it effective.

Hassan Dhaini, an environmental expert, argues (2) that the law commissioned the Ministry of Environment to set general policies regarding climate change, yet it did not allow the ministry to practice its role in oversight, just like "a surgeon working without a scalpel". In reality, the roles were divided as follows: the municipalities and the Council for Development and Reconstruction are responsible for sweeping and collecting the garbage while sorting and composting plants are mostly run by the Ministry of Administrative Development, and the landfill projects are managed by the Council for Development and Reconstruction. This brings us to the garbage crisis.

• Toxic waste mountains

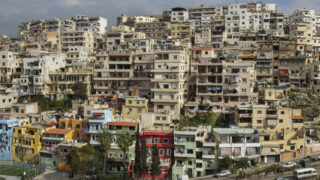

Garbage piles spread all over Lebanon forming huge “garbage mountains” which are arbitrary landfills that were established during the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990) on the coasts of Beirut, the capital city; Tripoli, the capital of the North and the second largest city; Saida, one of the big cities of the South, and in other locations all over the country.

Waste fermentation emits CO2 and methane, and the mountains of garbage adjacent to the coast produce toxic leachates that pollute the soil and groundwater and destroy the biological diversity in the Mediterranean. The effects of these emissions and leachates can be traced to climate change. There are 941 landfills in Lebanon and although Human Rights Watch has sounded the alarm about them in 2017, Lebanon has not taken a single step toward any kind of solution.

On the other hand, the disastrous state of those landfills has led to the ratification of law 80/2018 for Integrated Solid Waste Management, which consists of some nonbinding recommendations in 29 articles. Terms like “reducing”, “as much as possible”, “it is necessary”, and “facilitating” are frequently repeated. They neither prohibit nor impose anything, yet they are the “best available option”, according to a Parliament member who was bothered by the criticisms to the law since Lebanon would be deprived of the CEDRE (3) grant if it appeared to be unconcerned with the garbage problem. Political officials in Lebanon weaponize the garbage issue for their own clientilist ends; they see it as a huge financial resource through consensual contracts and a business network of interests, in which they are linked with the contracting companies through relations of kinship and/or public and discreet partnerships.

• Garbage fires

Since last September (2022), the Tripoli landfill has witnessed several fires, leading the Minister of Environment to announce a tender to shut down the dump. These fires are no surprise; they are the result of administrative measures the government took three decades ago. The Tripoli landfill burned for the first time in 1998, but no alternative solution for it was proposed until 2018, when it was decided to build a “temporary sanitary landfill” that paved the way for an imminent environmental tragedy. The “tools” of this tragedy were applied on all measures and procedures that deal with waste (Saida followed suit in 2016): the landfill was built without studying its environmental impact or building a proper plant for sorting and composting waste into organic fertilizers. These piles of garbage in Tripoli are located near residential neighborhoods, workshops, the port, the commercial center, the new vegetable market, and the old slaughterhouse that was shut down by the Ministry of Health for lacking the minimum technical and health requirements (today a new slaughterhouse is being built in its stead).

Tripoli’s landfill was barely cooling down when Saida’s landfill fire began on the 17th of October 2022. Meanwhile, narratives of containment ignore sustainable solutions, and the rehabilitation of dumpsites is done through wither expanding their areas or building support walls around them! These measures are always taken years after the landfills have reached the stage of complete saturation, leading to their collapse or catching on fire.

• Extending destruction: Coastal landfills

There is no immediate solution for the garbage mountains whose effects on climate change is devastating. These arbitrary dumps store large amounts of combustible biogas, which could only be extracted by digging wells and must be burnt in a safe manner. In the Tripoli landfill, work was halted in all wells and incinerators in 2013 after the surplus garbage piles buried and broke them. Following the Beirut port explosion on August 4, 2020, the people of Tripoli became unsettled by the presence of the landfill. When scientific reports confirmed that the imminent combustion of the garbage, the Council for Development and Reconstruction announced two tenders to close the dump, to which no one applied due to the financial crisis.

The overdue “solution” of closing the landfill that was supposed to take place in 2018 is but a result of irresponsible solutions. The contractor was granted extensions in 2003, 2008 and 2013 because the municipality of Tripoli could not decide on an alternative landfill. In 2018, the "sanitary and temporary landfill” was approved, alongside an adjacent sorting and composting plant (which was also awarded to a contractor). The factory, now closed, was emitting suffocating and polluting fumes. It had also been closed three times before due to its poor performance. And while the process of legal accountability for the unauthorized "transport" of equipment from the factory is moving incredibly slowly, all the garbage of Tripoli and the neighboring towns of El-Mina, Baddawi, and Qalamoun continue to be dumped in the landfill. Experts say that the economic crisis has reduced the production of garbage by 100 thousand tons annually, thus slowing down the saturation of landfill. Nevertheless, the authorities did not benefit from the time gained, as they see no other solution than extending for the landfills and causing additional pollution.

"You stink": Dirt, centrality, and waste

What is happening today is a scenario reminiscent of that experienced in the garbage crisis of 2015, which triggered widespread popular protests under the slogan "You stink." The protests in the capital and other central cities faced violent crackdowns by security forces, but the authorities continued to widen the scope of the destruction: expanding the Bourj Hammoud landfill in the northern suburb of Beirut vertically and reopening the Naameh landfill in the southern suburb of Beirut for two months, in addition to developing three coastal landfills in Beirut. In April 2020, the Bourj Hammoud landfill reached its maximum capacity again and was re-expanded vertically.

The garbage crisis is correlated with financial waste in a direct causal relationship. According to the UN Development Program, the cost of environmental decline in the solid waste sector was around $200 million in 2018. At the same time, the contracting private company that has been handling, since 1996, collecting and treating the garbage in Beirut and Mount Lebanon, makes an annual revenue that exceeds $170 million, which is the highest waste management revenue in the world. Lebanon spends $154.4 to manage a ton of solid waste while Algeria, Jordan, and Syria spend $7.22, $22.8, and $21.55, respectively. The situation worsens, as the state, with its collapsed institutions, struggles to survive, not to mention the financial crisis that undermined the profits of the contractors, thus increasing the cost of transporting garbage and leaving piles of trash to accumulate everywhere.

Electric power: A carbon network

In 2015, World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim lectured (4) in several renowned universities, sharing his commandments for the survival of our planet: “the economy should continue to grow. This is unquestionable… But what we should do is separate economic growth from carbon emissions”. In this respect, Kim made five recommendations, including “lifting fossil fuel subsidies, the efficient use of energy and using renewable energy substitutes, and fighting climate change in every way we can.” Practically, however, Lebanon contributes to climate change in every way. Fuel subsidies were lifted in 2022, but only as a result of the financial collapse and the loaning conditions of the World Bank, not for climate-related considerations. Lebanon consumes polluting energy to generate electricity, and there are no indications that it will be replaced by green energy anytime soon.

- Lebanon has depended, since the 1970s, on thermal power plants to generate electricity. These plants use fuel oil, and diesel or gas oil instead of natural gas, which causes more pollution and costs more money.

- There are seven old thermal plants in Lebanon whose performance is inefficient and which are in need of maintenance. These plants are: Jiyeh (1970), Zouk (1984), Sour (1996), Baalbek (1996), Hreisheh (1996), Zahrani (1998), and Deir Ammar (1998) .

- According to the 2020 figures, Lebanon produces around 2000 Megawatts annually, while its need exceeds 3600 Megawatts, and the deficit is rising.

- A parallel illegal network of privately owned generators to produce electricity has been expanding for the past thirty years. The owners of these generators are “the lords of the crisis,” according to citizens, as these generators monopolize the electric supply, benefiting from the almost total lack of regular (state-supplied) power. The number of private generators exceeds 7000, leading to a spike in carbon emissions. This “business" is not subject to taxation, and its annual profits are estimated at more than 2 billion US dollars.

- The first electricity plan was drawn up in 2010. It was based on building thermal plants to bridge the deficit, but without taking climate change into consideration, as the plants were set to utilize fossil fuels. This plan was also “temporary” since it relied on renting fuel/gas carriers. The Parliament approved another plan in April 2019, which is not much different than the first one in its details.

The electricity issue takes center stage in the Lebanese debate, yet it is trapped in the whirlpool of political biddings and exchanged accusations regarding accountabilities, without the slightest consideration of climate change or ideas that bring forward issues like “the green economy.”

Forests turn to ashes, but…

Scientific research confirms that deforestation, as well as other behaviors of land exploitation, is responsible for about 25% of greenhouse gas emissions. This is quite evident in Lebanon, where there is no responsible governmental agency that manages forests and stops their decay by wildfires, or protects mountains from the stone crushers that erode vast areas to produce white cement.

On forest fires: Forest fires and climate change in Lebanon interact in a vicious circle. The rise in temperature, one of the main manifestations of climate change, ignites fires in the green landscapes, in addition to certain deliberate human actions, such as firewood gathering for heating purposes, which has increased with the ongoing economic crisis since 2019.

In 2019, the number of fires multiplied and their scope widened. The Civil Defense recorded 100 fires all over the country. George Mitri, Director of the Land and Natural Resources Program at the University of Balamand, pointed that in 2019 and 2020, 3000 and 7000 hectares of Lebanon's forests were burnt respectively, which is 3 and 7 times the average annual rate of burned forest areas.

Meanwhile, the authorities ignore these climate change alarm sirens. Lebanon supposedly embraces a green ecological reservoir that occupies 24% of its overall area, divided between 13 % of forests and 11% of woodlands, but instead of acting as a nature-given lung that combats climate change, the forests have turned into a curse that contributes to climate change.

On the other hand, there is one exception; a success story that must not go unmentioned, as it counters the authorities' shortcomings and environmental crimes. It is the experiment of the Minister of Environment who succeeded in 2022 to reduce forest fires by 91.7% in comparison with the three previous years. To achieve this outcome, the Ministry did not invoke additional budgets or regulatory acts. Rather, it mobilized already existing human and scientific resources (especially in the Ministry of Interior through Civil Defense and the Ministry of Agriculture through the Forest Rangers), the Army, disaster management units in municipalities, volunteers, reserve committees, and research centers… This successful endeavor sets an example to be adopted for the efficient management of forests, as it succeeded at a minimal cost in activating the monitoring, prevention, accountability, fast intervention, and raising the level of environmental awareness.

On stone crushers and quarries: Instead of encouraging forestation, stone crushers and quarries are left to gnaw at Lebanon’s green landscapes, exploiting the “mummified” laws (decree No. 8803/2002 regulating stone quarries) and reaching 1356 quarries and crushers countrywide. Although it is in the jurisdiction of the National Council for Stone Quarries and Crushers – chaired by the Minister of Environment - to grant approval to new quarries, it is the Governor who holds the authority of issuing licenses. Sometimes the law itself acts as a cover for the violation, such as the license to “reclaim land,” which is in the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Agriculture, and provides a pretext for quarries.

The Minister of Environment has unveiled that the estimated due revenues that the quarries and crushers should pay to the government, after studying only 20% of the files, turned out to be 1.2 billion US dollars, while the total amount of unpaid revenues is estimated to be over 7 billion US dollars. This is how the whirlpool of hierarchies and the mazes of law work, providing a generous source of wealth for those with influence.

The Beirut Port blast: Undeniable damage

On the first anniversary of the Beirut Port blast, the United Nations has asked the following question: “After the explosion of the Beirut port in 2020, what lessons can be learned regarding the storage and transporting of hazardous materials?” Since the disaster, European companies, especially French and German ones, have been racing to undertake and improve disaster management at the port, well aware of the profits they would be making.

Lebanese authorities have gone out of their way to obstruct the criminal investigation and cover up for the involvement of high-ranking Lebanese officials in the explosion. Since July 2022, Lebanon has witnessed, over four stages, the collapse of the grain silos whose enormity and reinforced concrete structure blocked the wave of the blast, which would have otherwise destroyed the entire city. However, it seems the Lebanese were aware, from the very first day that followed the explosion, of who was responsible for their tragedy; the graffiti on the wall of the port read: “My government did this.”

In February 2021, the German company Combi Lift finished processing 52 containers of highly hazardous chemicals discovered at the port; the project cost Lebanon $3.6 million. Except for removing some iron and using it to make profits, the Lebanese authorities failed to lift the rubble, and the commissioned local teams could not handle the gigantic task.

An international report provided evidence (5) of criminal behavior in the mismanagement that caused the port blast by allowing the unsafe storage of 2,750 tons of Aluminum Nitrate for six years. Furthermore, the Lebanese authorities are not disquieted at all by the harm caused by the August 4 blast, which includes massive amounts of pollutants that deteriorate the environment:

- The video of the blast clearly shows an orange mushroom cloud. According to specialists, this indicates the presence of toxic Nitrogen Oxides (NOx), which are highly reactive substances that transform within a matter of hours into Nitric Acid compounds and to rain on the following day. Luckily, the winds that accompanied the blast diluted the concentration of the gases. The cloud was also accompanied by the emission of other toxic gases such as cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and particles of soot. This dust was mixed, according to Lil Ilm (6) Magazine (Scientific American Magazine), with fine particles of glass splinters in the air… And Beirut had to breathe all that yet again.

- The threat of car batteries and electronic wastes, such as the destroyed computers whose remnants most commonly include Cadmium, Lead, Lead Oxide, Antimony, Nickel and Mercury, which are poisonous elements and compounds that release climate-damaging gases. Moreover, these kinds of waste require a special kind of management that is not available in Lebanon.

As the planet becomes increasingly attentive to the top priority and urgency of fighting climate change, Lebanon continues to fall into deep slumber... If it happens to make any kind of move in this respect, it would certainly be in the context of a heated race between the parties in power to deplete, relentlessly and shamelessly, the natural resources of the country.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Ghassan Rimlawi

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 05/12/2022

1- A report by UNICEF: The water infrastructure in Lebanon is on the brink of collapse and the prospects for a solution are dim. United Nations Website, July 2022. https://news.un.org/ar/story/2022/07/1107462

2- The Ministry of Environment: Challenges, jurisdictions, and priorities. December 2021.

https://www.imlebanon.org/2021/12/08/ministry-of-environment-crisis/

3- On the CEDRE grant see: https://bit.ly/3EXYpEA

4- Five ways to reduce climate change. World Bank Website. March 2015.

https://bit.ly/3gVZ15B

5- Human Rights Watch website: They Killed Us Inside: An Investigation into the August 4 Beirut Port explosion. September 2021.

https://www.hrw.org/ar/report/2021/11/12/379416

6- The Beirut blast: The Journey of toxic gases and their harmful effects on the environment, Scientific American Magazine website. August 2020. https://bit.ly/3gYUgbm