This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

To reflect on public perceptions, as opposed to the lived reality, of women, I revisit the letters written by the late Etel Adnan [1]. Gathered in a book titled Of Cities and Women [2], and in her conscientious and sensitive wanderings throughout the different cities she visited around the world, from London, to Barcelona, Frankfurt, Beirut, and others, her writings explore not only the cities’ conditions, but also those of its women. For instance, Adnan shares her enthusiasm about Barcelonan women’s liberty in managing their bodies in public spaces in any way they like. She finds some form of unity in their personalities, between what goes on in their minds and their daily practices. She says that they remind her that “it is interesting to be alive, to be human, and to be part of a specific moment in time and space…”. In her reveries and notes, she places “experience” many levels above mere “theory”[3]. Cities are made up of all the events they have experienced, and women’s lives are shaped by the experiences they go through, both internally and externally.

When it comes to women’s conditions in Lebanon and other Arab countries, a thousand other questions come up, perhaps all stemming from the question of “what it means to be alive and human”. It is perhaps also embarrassing that we continuously need (many) liberated and resistant models capable of living out such obvious humanity, be it in our own communities or beyond, for us to find meaning in seeking a world that fulfils this “unity” - as described by the multidisciplinary artist- between the space of internal desires and the achievement of such desires.

Of the one thousand and one questions, this article studies the situation of women all across Lebanon and the reality of their relationship with the law, religious legislation, and society. Were we to google two key words, “women” and “Lebanon”, we’d be disappointed as images and confusing links start coming up, reflecting strange definitions of women in Lebanon and their issues: “Lebanon’s women are the beauties of the Arab world”; “Who are the ten top most beautiful women in Lebanon?”; “He married me without dowry: spinsterhood infuriates Lebanon’s women!”. Such are the first few links that come up, with a collection of “sexy” women’s pictures everywhere, from performance platforms to popular protests. After a few such headlines, a different link comes up, with a title of “Period poverty” in Lebanon, followed by another on violence against women and their need for protection. Both of these indicate yet another reality, both old and new, which is unveiled as soon as we delve deeper in to our search. How do Google’s “algorithms” match mainstream media’s presentations of Lebanese women? What is certain, though, is that barring a few alternative media websites and activist-run social media pages, “Lebanon’s women” are still a clichéd fantasy, tempting voyeurism and entertainment and, thus, inspiring a superficial representation of their issues.

No paradise for women

That negative reductive image is paralleled by a positive reductive one, which occupies many an imagination in Lebanon itself as well as in neighbouring countries. The saying goes that Lebanese women are, in the end, in a “good place”, especially in comparison with other women in the region. Presumably, Lebanese women are liberated and somewhat free to choose what they wear, mingle with men, and leave home for studies and work. Such impressions are once again reinforced by the images that the media generates, with an abundance of clichés: “Here, hijabs and bikinis coexist”, “Women in Lebanon can enjoy their nights out safely”, “In that sense, it’s like we’re in Europe”, and so on. Many women from Egypt, for instance, suffer widespread harassment, and are monitored and oppressed, by all kinds of big and small patriarchal entities, who are dangerous nevertheless. Patriarchy is the state itself (that locks up girls for no other reason but making fashion or dance videos on TikTok), the building guard (who, in most cases, is authorised to prohibit a woman resident from hosting male friends, sometimes to the point of assault and murder, as in the case of the Salaam City doctor) [4]. It is thus assumed that Lebanon provides much more comfort for women when it comes to public and private spheres.

Were we to google two key words, “women” and “Lebanon”, we’d be disappointed as confusing images and links start coming up, reflecting strange definitions of women and their issues in Lebanon: “Lebanon’s women are the beauties of the Arab world”; “Who are the ten top most beautiful women in Lebanon?” After a few such headlines, a different link comes up, with a title of “Period poverty in Lebanon”, followed by another on violence against women and their need for protection.

To an extent, and generally speaking, that could be true. However, relative and seeming comfort quickly make way to expose the many layers cumulated and entrenched right underneath. Violence and misogyny trivialise women and deride their human value, which is supposed to be one of life’s clearest givens. In any case, none of this is meant to compare “Which of us is more oppressed?” – such questions are counterproductive, and even harmful to women’s causes.

“Nakad”: that sly trick to silence women

01-01-2022

If this is the apparent state of things and what is commonly perceived of women in Lebanon, questioning it would require looking into several aspects of real life. Those would include Lebanon’s conditions and the implications that result therefrom, along with their complexities, be they related to social customs or sectarian politics. Below are three categories that aim to study the actual, rather than the illusory, picture of women in Lebanon.

First: Law, Sharia … and society

The Human Rights Watch report, Unequal and Unprotected: Women’s Rights in Lebanon under Lebanese Personal Status Law concludes that treating women justly before the law falls short in Lebanon. Based on a review of personal status laws in Lebanon, of 447 court decisions issued by several confessional courts (until 2015), and more than 70 interviews with women, lawyers, judges, social experts, and women’s rights activists, the report reveals a clear pattern of ill-treatment of women in a much graver manner than men when it comes to the option of filing for divorce and children’s custody. And here, I refer to all “the different sects”, whereby individuals’ personal status in Lebanon falls under the jurisdiction of 15 codes for 18 religious sects. These run each sect’s members affairs, as no civil personal status law exists in Lebanon [5].

For example, the Sunni and Shiite laws in Lebanon guarantee men an absolute right to divorce, whereas women could only obtain that right conditionally. A woman must have been granted the right to get a divorce (issma) by the marriage contract first – which itself remains very rare, rejected by society anyway to a large extent. On the one hand, in some religious courts, “those menstrual hormonal shifts” are used for an excuse, as women “fail to make the right choice in that condition”. “How then shall they be given the right to divorce?” [6] On the other hand, the problem, just as important, is also present through social conventions. Human Rights Watch itself reviewed 150 divorce orders issued by Sunni and Shiite courts, and found that only three were fulfilled based on the wife’s right to issma. One of the women included in the interviews, Nour (31 years old), said: “Our customs do not allow it. How do I ask for such a thing and imply that my husband wasn’t man enough?”. Likewise, other women expressed their own personal rejection of issma, who saw in it an act of doubting a husband’s kindness and reasonableness. In several cases, things reached a point of breaking off an engagement as soon as the fiancée or her parents mentioned divorce conditions.

Additionally, the mainstream Lebanese media, especially TV channels, reproduces the same tacky and superficial images of women in Lebanon, resorting to a vocabulary that combines “seductiveness, culture, and liberation” and other self-praising descriptions. In so doing, they disregard the reality of thousands of women who live cruel and violent conditions on every level.

Many women joke about a deferred dowry by saying: “If I wanted a divorce and my life became hell, not only would I give up all my rights, I’d also pay the dowry myself so that my husband would leave me alone.” As such, these social premises sometimes create more pressure than religious Sharia does. They also hinder the largescale adoption of women’s rights, even if it served their own good. 23 out of 27 women interviewed for the report confirmed that the main obstacle they faced in trying to get a divorce was the economic vulnerability they suffered throughout and after the divorce procedures, due to sustained economic dependence on the husband.

Were we to reflect on the Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Evangelist courts, similar discrepancies would come up. Despite the firm restrictions that stand in the way of dissolving a marriage contract, equally imposed on both men and women in Christian denominations, unlike women, men have recourse to get around the law and manoeuvre it. For instance, to the Greek Orthodox, a man has a right to divorce if he found out, following the marriage, that his wife wasn’t a virgin. Moreover, domestic violence isn’t considered enough reason to end a marriage, unless it reached homicidal levels!

The organisation Fe-Male has also recorded 27 misogynist crimes against women and girls in Lebanon in 2020, as opposed to 13 crimes in 2019 and domestic violence crimes, at a rate of two crimes per month.

As opposed to the abovementioned, civil marriage and proposed acts to unify personal status codes are met with extreme resistance, on many a different level – not only from religious men and religious courts, but from a high percentage of the Lebanese population. According to the latest statistics conducted by the International Information Network in 2016 [7], a high rate of 42 percent of respondents in Lebanon endorsed the idea that religious marriages should remain under the authority of Muslim and Christian courts, while 41 percent advocated for a freedom of choice between civil and religious marriages, whereas only 4 percent agreed that civil marriage should be standard in the country (as opposed to 7 percent who showed no interest in answering the question). Such examples and other relevant rates help paint a picture of the way sectarianism and its laws work. Likewise, examples abound that show how social conventions steer perceptions of personal status laws, which discriminate against women.

Second: Equality in education and work?

Lebanon occupies an important rank in terms of elementary school enrolment rates. The net rate reaches around 90 percent for both sexes, while the gender parity index determined in the statistical report on gender in Lebanon [8] affirms that no gap exists in that domain. As regards higher educational levels, the report notes that the net enrolment rate for females is higher than that of males. According to the same report, a huge gap is noted in the job market; while women made up 52.6 percent of the working-age population, less than 30 percent actually participated in the job market. Likewise, stereotypes still affect women’s career choice, whereby 9 out of 10 women work in the service sector, while their participation in the industrial and agricultural sectors remains very limited. Additionally, the wage gap between men and women is maintained, whereby statistics show that the average wage of Lebanese women is less than that of Lebanese men by 6.5 percent.

Civil marriage and proposed acts to unify personal status codes are met with extreme manifold resistance – not only from religious men and courts, but from a high percentage of Lebanese men and women.

It is true that “women work”, and in daily conversations, opinions such as “Women’s presence has increased in all markets to the point that they’re now snatching men’s jobs” are often heard, just like the question “You’re demanding equality and liberation? What do you want more than this?”. Sceptics might express confusion in understanding women’s problem with their reality; notably, their confusion is not devoid of aggression or sarcastic accusations, and may be expressed equally by women as well as men. Customs and prevailing social patterns still control not only the domains in which the majority of women end up, but also the positions women hold within these domains.

Despite the elevated rate of women holding senior and mid-level management positions in the public sector, which rose from 30 percent in 2004 to 42.3 percent in 2018-2019, their presence in the private sector still does not exceed 26.5 percent in many different institutions, including those in the service sector.

On the other hand, concerning the domestic conditions women live and the economic vulnerability they suffer, we note that women often find themselves governed in their own money as well, with no religious or legal justification. There are countless examples of educated and working women, in all lines of work, from impoverished and middle-income families, who still get robbed of their labour, and find themselves stuck in a cycle of economic dependence. As such, they’re forced to ask for money, that they made, whenever they needed anything. Furthermore, stay-at-home women are considered neither by law nor by social convention to be fulltime labourers who deserve to be paid for their labour; and are thus rendered completely dependent on their partners.

Third: “Consuming” women in media

A WhatsApp message shows the image of two women with saggy skin and dark circles under their eyes. The caption says: “Lebanon’s women, post economic collapse and discontinued Botox operations”. The person who sent the image was a woman and the group to which it was sent was a women’s group. This picture, and others with similar implications, often do not beckon women’s disapproval, sometimes rather inspiring laughter.

While women made up 52.6 percent of the working-age population, less than 30 percent actually participated in the job market. Likewise, stereotypes still affect women’s career choice, whereby 9 out of 10 women work in the service sector.

Such images that easily judge women’s bodies are replicated, as a form of “wittiness”, with no parallel circulation or reinforcement of positive perceptions of women. There is little mention of the fact that it was women, for instance, who collectively rose up to find alternative work, even if it be through merely offering to cook from home to potential clients, to support their families, as many male breadwinners lost their work value with the collapse of the national currency. One also finds the same negative focus circulated through a song like “Jumhouriyet Albi” (“Republic of My Heart”) by singer Mohammad Iskandar, which reaped widespread popularity when it was released in 2010. Its lyrics go as such: “Degrees and jobs are not for our girls; our girls must be spoiled, money brought their way”. The song ends with the singer saying that suffice it for the girl to be the “President of the Republic of his Heart” – as that should be the highest position to which a girl should aspire. What is certain here is that such pop music isn’t limited to uneducated classes or early marriages that resulted in the inability to find work at all; rather, such songs resonate loudly in the wedding parties of all social classes, be those in villages or cities. In the vast majority of cases, such songs neither urge reflection nor profound critique of the meanings and messages they connote. In the best of scenarios, when such songs aren’t met with approval, critique considers them harmless jokes or just simply entertaining talk.

Additionally, the mainstream Lebanese media, especially TV channels, reproduces the same tacky and superficial images of women in Lebanon, resorting to a vocabulary that combines “seductiveness, culture, and liberation” and such other self-praising descriptions. In so doing, they disregard the reality of thousands of women who live cruel and violent conditions on every level. On the other hand, when the media reports cases of discrimination and problems that women face, it only focuses on simplistic aspects and rarely manages to advocate for such causes. The TV host, Rabia Al-Zayyat, for instance, wonders in the trailer for her TV show “18+” on Aljadeed Channel: [9] “Do you agree with the expression that says that the beatings of a lover are sweet?” She thus presents the question of beating women as a viewpoint that begs dissenting or concurring opinions, to be expressed by both men and women she hosts on her show. As such, she replicates the picture presented in previous interviews where Lebanese artists expressed shocking opinions in that regard. Singer Najwa Karam, for instance, said that it was “good for women to feel a man’s strength” if he hits her for raising her voice at him. Likewise, actor and former Miss Lebanon Nadine Njeim’s mirrored the latter, saying that she indeed would never raise her daughter as she raised her son.

Women often find themselves governed in their own money as well, with no religious or legal justification. There are countless examples of educated and working women, in all kinds of work domains, from impoverished and middle-income families, who still get robbed of their labour, and find themselves stuck in a cycle of economic dependence. They’re thus forced to ask for money, that they made, whenever they needed anything.

It may be easily seen then how the rug is pulled from underneath a serious treatment of such questions, making room, once more, for what’s presumed to be entertainment, but what in fact turns a blind eye to a bad and humiliating situation that most women live, reproducing severe notions and values, helping to perpetuate them.

Multiplied fragility in times of crisis

Notably, beating women, for instance, is presented in such a way at a time when the economic crisis and violence against women has been shown to be closely tied – as noted in a recent study conducted by ABAAD Organisation [10]. The organisation Fe-Male has also recorded 27 misogynist crimes against women and girls in Lebanon in 2020 [11], as opposed to 13 crimes in 2019 and domestic violence crimes, at a rate of two crimes per month. In 2021, 3 women were killed in one week by one of their family members. The crime-rate increase in Lebanon in 2020 reached a shocking 107 percent when compared with 2019. The number of complaints received by the internal security forces through the hotline (1745) has also grown, from 747 states of domestic violence pre-Covid-19 to 1468 complaints during the lockdown. The rate of reporting domestic violence has increased by 96.52 percent post-Covid-19.

Likewise, a rise in unemployment rates was noted this year; it reached 75 percent among women, who were discharged from their jobs in large numbers. This too, is one of the knock downs of the economic collapse, just like “period poverty” – embodied in a 500 percent price increase for sanitary pads and menstrual supplies; whereby 76 percent of women in Lebanon find it difficult to purchase them.

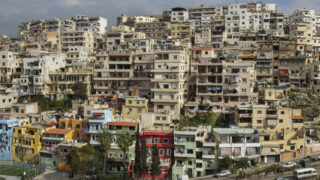

In the face of deteriorated living conditions and women’s vulnerability, especially in marginalised groups, a few important paradoxes are laid out as a response to all the reductionist answers about women’s situation in Lebanon. They lift that thin veil to expose dangerous conditions, where impoverishment partners with sectarianism and legislation impasses entwine with the usual patriarchal conventions – to create an environment that perpetuates discrimination and violence.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 14/12/2021

[1] She passed away at 96, on November 14, 2021.

[2] Of Cities and Women: Letters to Fawwaz is a book composed of a collection of letters written between 1990 and 1992. Beirut: Dar Annahar Publications, 1998.

[3] Mouna Taqieddine Amuni, in Al-Raida Journal. Amyuni, M. T. (1). Etel Adnan on The Secret of Being a Woman. Al-Raida Journal, 24-25.

[4] A 34-year-old doctor was assaulted and pushed from the sixth floor in March 2021. She fell and died at the hands of the building owner and his wife, because they suspected she had hosted a male friend in her apartment in Assalaam city in Cairo.

[5] Fatima Al-Moussawi and Sarah Al-Banna’s report, titled “Breaking the Mold” – Issam Fares’ Institute for Public policy and International Affairs. More info through : https://bit.ly/3tsfFOa

[6] From a testimony from a Human Rights Watch report, which can be read fully here: https://bit.ly/3trPRkU

[7] For more, see: https://bit.ly/3KcYcio

[8] Issued by the Central Administration of Statistics in partnership with the UNDP in October 2021. https://bit.ly/3tznwsW

[9] The episode was broadcast on November 30th, 2021.

[1] A study commissioned by ABAAD Resource Center for Gender Equality to Statistics Lebanon Ltd. And titled “Women’s and girl’s priorities in Lebanon and the extent of protection they need”.

[1] As per a report of the National Media Agency, written by Oumayma Chamseddine.