This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Contrary to all predictions of a catastrophe, the Algerian healthcare system did not collapse with the Covid-19 pandemic, that is, in spite of weakened political and financial conditions that spur “the people” against what is called “the system” in Algeria, charged with corruption and despotism. It did, however, reveal its profound fragility.

It must be noted that the healthcare system has also benefited from a primarily mild and merciful development of the pandemic. According to the latest official report by the Ministry of Health, Population, and Hospital Reform, the only authorised source on the matter, the overall number of confirmed cases since the beginning of the pandemic and until April 15th, 2021 reached 119,142 cases and 3,144 deaths, in a country with a population of more than 40 thousand.

Algeria, which believes in no “miracles”, keeps its guard up and watches with apprehension the development of two new variants: the “British variant” and the “Nigerian variant” – between its northern borders, Europe, and its sub-Saharan African borders, between its immigrants and expats, neither of whom is currently welcome into its territory.

After a temporary lull in infections, the curve has been rising ever since March 15th. The number of cases has risen from a hundred cases a day to 167 newly confirmed cases in 24 hours, with an average of four deaths a day.

In the meantime, and up until today, the evolution of the pandemic that has baffled experts all over the world has disproved the catastrophe that even the Director-General of the World Health Organisation, Mr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, had predicted on March 20th, 2020, by calling on Africa to awaken and prepare itself for the worst. As if Africa could dose off, indifferent to a changing world.

According to the latest official report by the Ministry of Health, Population, and Hospital Reform, (the only authorised source on the matter), the overall number of confirmed cases since the beginning of the pandemic and until April 15th, 2021 reached 119,142 cases and 3,144 deaths, in a country whose population has more than 40 people.

However, far from such entrenched prejudices of a somnolent Africa, this pandemic will, as Algeria would show, reveal the profound upheavals that shake and move this continent. Faced with cumulative transitions that add up to an inflammable future: between epidemic shifts, demographic shifts, and an economic transition from a centralised economy to a market-based economy.

Since the 2000s, Algeria has moved from fighting communicable diseases, contained through massive vaccination campaigns, and raising the standard of living, to the management of new chronic diseases, like cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. The age pyramid evolved: 10% of the population was now over the age of 65, inducing an increase in healthcare needs. As social security state resources dwindled, households were given an extra burden, while entire social sectors slipped into impoverishment. This sets up Algeria as one of the most impacted countries if considered in terms of Covid-19 deaths of the population older than 65. The same applies to South Africa, where, according to WHO, less than 5% of its population is older than 65.

The Hirak in Lockdown Algeria

02-02-2021

2019-2020: Algerian Power versus the Hirak

10-02-2021

The Covid-19 pandemic would reveal all the transformations at work in the heart of the Algerian health system. It would reveal a tendency to empower the private health system, a minority for the time being, by a particular division of labour, to the detriment of the prevailing public sector. Public/private is how the Algerian imagination has learned to comprehend its healthcare system. The public system: overloaded, critiqued, undervalued, overcrowded emergency rooms, counting the dead. The private sector: new clinics, laboratories, and diagnosis. Public services: free health care and public facilities. Private services: benefits and investment. A shift that would be further confirmed through the management of this pandemic. Those who govern Algeria lack transparency and give speeches that can no longer hide the truth about a resolute tendency to undo the freeness of healthcare instilled in 1974.

From defiance to violence

When, in March 2020, the first Covid-19 cluster was diagnosed in the Blida Province, which resulted in the first death, a woman announced the spread of a virus “the kills”; between March 19th and 27th. The Minister of Health reported 26 deaths and 409 confirmed cases. A real wave of panic took hold of social media when numerous young doctors posted pleas calling for vigilance, dreadfully begging Algerians to “stay home”, thus sharing their anxiety-inducing experience in public healthcare facilities – unfit to receive serious cases of respiratory distress.

The Covid-19 pandemic would reveal all the transformations at work in the heart of the Algerian health system. It would reveal a tendency to empower the private health system, a minority in the past, by a particular division of labour, to the detriment of the prevailing public sector. The public system is overloaded, critiqued, undervalued, with overcrowded emergency rooms, counting the dead. The private sector: new clinics, laboratories, and diagnosis.

When President A. Tebboune, aged 75, in turn caught the virus, seven months later in October 2020, he would evidently go for treatment… in Germany. As such he followed in the footsteps of his predecessor, A. Bouteflika, who had treated his heart between Switzerland and France.

To society, the message was loud and clear: neither medical personnel nor governments trusted the Algerian healthcare system. A message with disastrous effects that aggravated the disintegration of social relations between society and public facilities. It resulted in the denunciation of the state as fused with the government and its loathsome and appalling ruling class.

A situation that has become a real breeding ground for insecurity and violence in hospitals, setting distressed people in emergency rooms against women, a majority, and men healthcare workers.

“…The situation is exacerbating thanks to the epidemic situation,” Lies M’rabet, member of the General Practitioners Union, thus writes worriedly in the columns of the daily Liberté on July 16th, 2020 – barely four months after the beginning of the pandemic. Already out of breath, workers are mistreated. They work under pressure, lack resources, and prohibited from taking leave, […] and separated from their loved ones. Besides living with the fear of falling ill.” As such, the two vulnerable populations clashed: medics against the medicated.

When President A. Tebboune went for treatment in Germany following healthcare personnel calls for staying at home, the message was loud and clear: neither medical personnel nor governments trusted the Algerian healthcare system. A message with disastrous effects that aggravated the disintegration of social relations between society and public facilities. It resulted in the denunciation of the state as fused in with the government and its loathsome and appalling ruling class.

But this is not the case everywhere. Such violence is almost exclusively exercised in public health facilities that prevail in Algeria. The Minister of Health at the time, Mr. Miraoui, “wondered” in surprise in an APS communiqué on July 30th, 2020, about the difference between citizen behaviour in public and private sectors […] while patient companions assault […] public sector employees in spite of the free healthcare they’re given, this very same group of citizens behaves itself when in private sectors.”

Such a situation is more unjust than usual. It would be the public healthcare workers that mobilise and challenge it: “The fighters in white coats” of the public sector have clearly proven their humanity and professionalism ever since the beginning of the pandemic in Algeria. Private sector physicians have also contributed by taking in patients,” as remarks Zoulikha Snoussi, a CREAD researcher (1), before clarifying that “physicians of this very sector have nonetheless preferred to close their clinics, despite a governmental obligation to ‘maintain their activity to avoid prosecution and penalties, and the immediate and definitive revocation of their medical license,’ as per the two adopted executive orders. (2) These private practitioners feared, however, and not without reason, they would incur infections in the shadow of scarce market supplies of protective gear.

“The fighters in white coats” of the public sector have clearly proven their humanity and professionalism ever since the beginning of the pandemic in Algeria.

On November 23rd, 2020, the Director of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Dr Djamel Fourar, estimated that deaths among healthcare workers were 120 and infected cases were 9,146.

Faced with all these difficulties, what would a government’s response be? Repression!

By tightening the penal code with new provisions (prison sentences from 2 to 20 years in jail) in order to ensure “penal protection” to healthcare personnel, as per the presidential decree of July 30th, 2020 and with no useless parliamentary debates. Incidentally, the latter has since been dissolved and awaits the legislative elections planned for June 2021.

Rare are the voices as publicly outraged as prof. Chaoui’s, a critical and respected gastroenterologist: “How were we supposed to respond to this disaster? Repress or rebuild trust without which no sustainable solution is possible?” He reminded that “One must bring about structural reform at the right time. Failing to do so has resulted in deplorable working conditions for healthcare practitioners and scandalous conditions of patient reception, leading to a loss of trust among all system actors. General discontentment of healthcare workers, administrators, funders, and, of course, users figure in the aftermath. The latter -users- pay the highest price, however. They have become intruders in the public healthcare system and highly billed ‘clients’ in the private sector.”

“Intruder patients” within the public system, “overbilled patients” in the private system: this is what it’s like to seek treatment in today’s Algeria – tossed around between these new dynamics, which healthcare anthropologist Mohamed Mebtoul pithily terms as “a twisted healthcare market.” The latter is a grand organiser of a “rapid and violent” “important shift”, ongoing since the 1990s.

Between the public and the private

Defining national healthcare politics has been falling further and further under external pressures, which drive public powers to explicitly favour an official discourse centred on the “integration” of the private health sector into the official healthcare system. In other words, this is a question of reconciling a mode of regulation centred on bureaucracy -as hospitals are run- with a healthcare sector “allowed” to develop with the consent of public authorities. Being currently impossible, integration is more explicitly a question of achieving “social peace” between healthcare bureaucracy and the private sector, thus producing this “twisted healthcare market”.

The general practitioner described private medicine as marginal when compared with the public healthcare system, organised by a pyramid structure whose base is made up of primary healthcare centres, which still prevail over the country, all the way to university health centres (CHUs), which are much scarcer. However, the authorisation of specialist private clinics in 1988 would completely change this order. Though set off to a timid start, these clinics would increase in number at an accelerated rate with the introduction of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SPAs) in 1994 and the redefinition of the role of the state.

Defining national healthcare politics has been falling further and further under external pressures, which drive public powers to explicitly favour an official discourse centred on the “integration” of the private health sector into the official healthcare system. In other words, this is a question of reconciling a mode of regulation centred on bureaucracy -as hospitals are run- with a healthcare

“As such,” Zoulikha Snoussi recounts, “the establishment of clinics became more pronounced with an average of 14 clinics a year between 1988 and 2006. Ever since 2007, the average was nine newly established clinics a year. In 2015, 237 medico-surgical clinics were created, along with 33 medical clinics that operated side by side with 8,352 specialist clinics, 6,910 general practitioner clinics, and 6,144 dentistry clinics. […] In 2005, 184 haemodialysis centres were listed […] Following the agreement signed with the social security system for a full coverage of haemodialysis healthcare expenses.”

The private sector thus focused on specialisation in new chronic diseases, equipped with innovative technologies that the public sector lacked, like scanners, colonoscopes, endoscopes, MRIs, etc. that were deficient and often broken in those overburdened public facilities. “It is not resources that we lack, though they are insufficient”, said epidemiologist Mohamed Yousfi, Head of the Blida Hospital department and Secretary General of the National Union of Public Healthcare Practitioners. “It is political organisation and will that we lack.” This impacts available specialist positions, over which the private and public sectors are competing. For example, ever since 1999, the law authorises specialists to sell their services to these new clinics as “complementary activity”.

“This is catastrophic”, Dr. Youssefi reckons. “As union members, we were against it. We said: you will destroy whatever’s left of public healthcare. Complementary activity now became a complementary salary. But seeing that it happened during the IMF rule and when people were underpaid – we let it go. However, when back then only specialists were concerned, now everybody works privately – from paramedics to janitors. To avoid deviations, two conditions apply to this complementary activity: the involvement of a strong management and a strong Professional Order – both of which are nonexistent. Wherein lies the absolute deviation: all private personnel are public doctors who work on the side, undeclared, in violation of the law. They do not observe the conditions stipulated in the law in terms of length, departmental presence, and writing out prescriptions made in their name – for tax purposes, which also impacts public facilities.”

To such purview “lucrative activity” was added in 2010, which equally allows university-hospital practitioners, specialists, heads of departments, and heads of units within the public sector to practice, in private facilities, a lucrative activity during weekends and statutory holidays. In conclusion, Prof. Metboul says: “The overlapping social logic of public governments employees and medical specialists well demonstrates a prevalent twisted healthcare market, which is at the root of an empowered private sector that feeds on malfunctioning hospitals and a bureaucratic and centralised management and regulation of health. Such overlap was cruelly illustrated as the pandemic unfolded.”

PCRs and medical scanners

As the pandemic was just beginning, only the Pasteur Institute, based in Algiers, was in a position to conduct virologic exams (PCRs/X-rays), that is, before setting up about thirty annex labs equipped with the necessary resources, though unequally distributed all over the national territory in order to achieve an average of 2000 tests a day.

Such capacities were rendered insufficient in between viral peaks (up to 600 vases a day) and lulls. In spite of their efforts, hospitals were about to quickly find themselves dealing with recurrent shortages and stock-outs of diagnostic equipment, reagents and consumables. The Algerian press would only echo the distress that hospitals expressed. In the meantime, and by default, ribcage CT scans would be recommended to test for a possible infection, though no precision was guaranteed. Worried and suspected of being carriers, patients would be left with no other choice but private clinics. While at it, the Scientific Committee for Monitoring the Pandemic unanimously issued “recommendations and general guidelines to MOH healthcare facilities to develop a collaborative strategy with these laboratories on the means and feasibility of conducting such tests.”

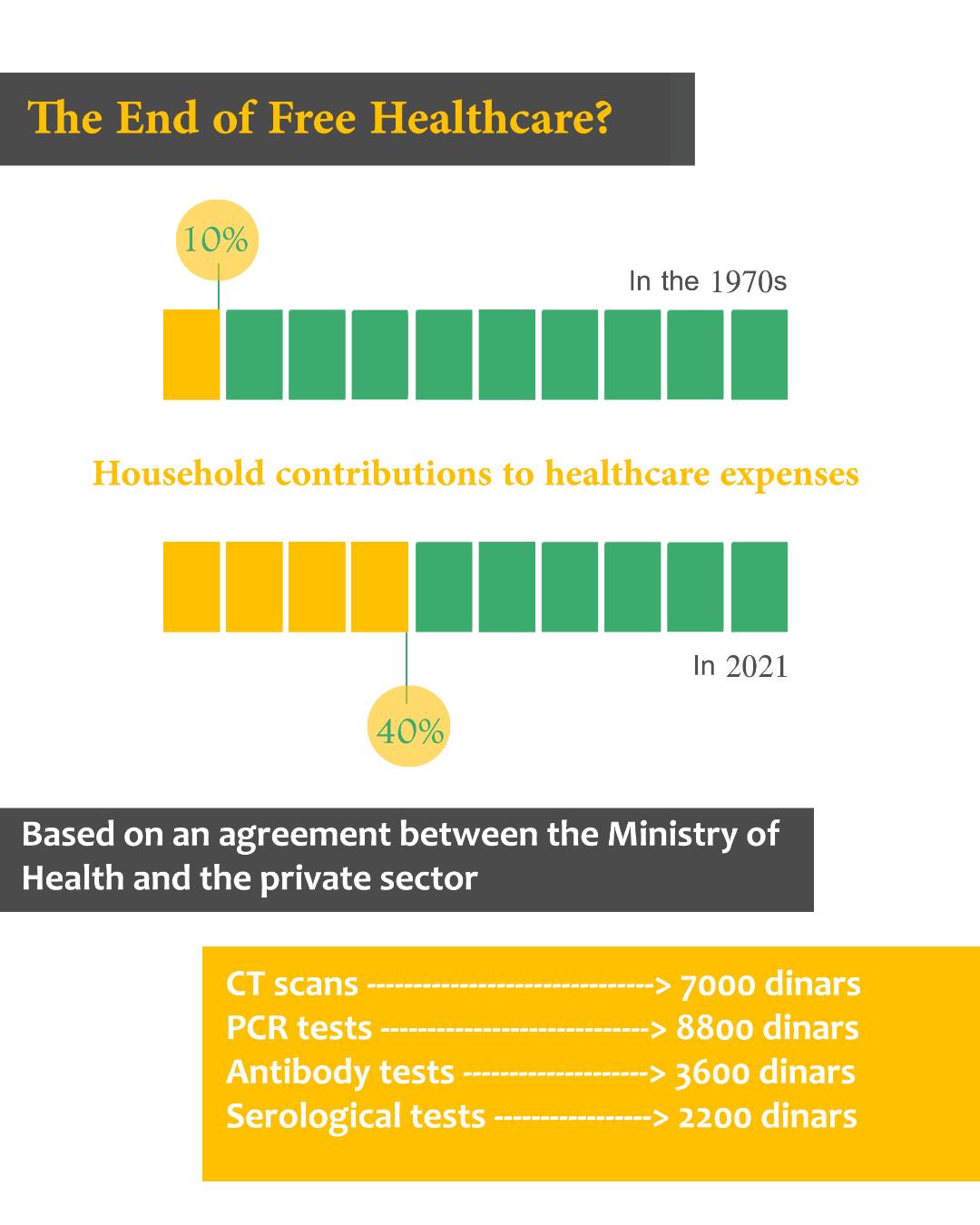

Tongue-in-cheek, but effective. On July 2nd, the Ministry of Health announced that “laboratories affiliated with the private sector could begin to carry out PCR testing in order to screen for Covid-19”. In record time, dozens would set themselves up, this once suffering neither shortages nor stockouts. The prices charged, however, were scandalous. To the point that Doctor Djerad’s government was forced to negotiate with the private sector, negotiations that would translate into a laconic communication by the official news agency, APS – “Coronavirus scans and medical test prices have been capped, by virtue of an agreement signed… between the Minister of Health, the Association of Private Radiologists, and the representatives of 11 medicals laboratories.” Scans were therefore capped at 7,000 Algerian dirhams, PCR testing at 8,000, serological tests at 3,600, and antigenic tests at 2,000.

Household shares of healthcare expenditure have continued to grow, rising from 10% in the 1970s to almost 40% today.

In the public sector, everything used to be free. Such tests, then, that the social security system would not reimburse and rather charge to households, became an increasingly heavy burden in a country with chronic unemployment, weighed down by 500,000 workers that the pandemic had recently unemployed. Today, it is estimated that in Algeria, household shares of healthcare expenditure continue to grow, rising from 10% in the 1970s to almost 40% today.

“This is the end of free healthcare”, Professor Farid Chaoui writes. He adds: “At the beginning, I thought that this was a mere deviation from the norm, a result of deficient healthcare policies. When one sees the different steps this healthcare system has taken, however, one realises that this is a deliberate policy. It consists of yoking households with an increasingly significant share of healthcare spending,” stuck between an authoritarian lockdown and tightly sealed borders.

“A deliberate policy” complemented by an authoritarian lockdown, unbearable to the majority of an impoverished population, an estimated 25 percent of whom suffers a housing crisis and unemployment, and who participate in an informal economy (making up 40 percent of its working age group, according to World Bank statistics). All this in the middle of a security lockdown that the sanitary crisis would only exacerbate. Ever since February 18th, 2021, all borders closed down on Algerians. They could no longer enter or leave without an “exit permit” – exclusively approved behind the closed doors of the Ministry of Interior. As such, a sick Algeria has been fulfilling one police force dream.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 11/05/2021

1-In “Le système de santé Algerien face à la crise sanitaire du Covid-19”, CREAD 36 :3 (2020).

2-(2020-70 of March 24th, 2020 and 2020-86 of April 2nd, 2020).