This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Imagine a narrow slope, behind hedges of bamboo, corn, fig trees, and pines, trapped between a mountain range and a putrid-smelling valley. The slopes tumble down the mountain for a few kilometres until they reach this steep field, revealing a view of the Mediterranean of striking beauty. It is there that men and women live in houses snatched from the midst of adversity by strength and courage, sharing this neighbourhood marked on no map.

Should you ask the inhabitants about the name of this place, the older ones would say it’s called “la Forêt” (“The Forest”), while the younger ones would say that it’s the “December 11 neighbourhood”.

To question these two names is to revisit the history of these houses, originally built on the margins of colonisation (1830-1962), before being added to the promises made for an independent Algeria (1962).

You’d learn that slums usually borrow their names from neighbours as one invents an address.

We’re now in the Aïn Benien commune, in the Algiers wilaya (governorate), 20 kilometres west of the capital. This commune was founded in 1872 and named after its founder, Count du Guyot: Guyot-ville. He instilled colonisation policies and, like Job, he was responsible for installing the poor settlers there.

While these settlers got richer off of the vineyards, the first Algerian inhabitants would come to settle by the edge of a beautiful forest that surrounded the place that became this shantytown, which they would call “La Forêt”, as the French called it.

Most of them were Kabyle, forced out by famine and unemployment, then by the war of national liberation between 1954 and 1962. They would earn their bread by working as “khammes” – that is, as agricultural workers.

Everything changed 57 years following Algeria’s independence… that is, except for social exclusion and its counterpart, spatial exclusion. The commune would then recover its original name, Aïn Benien, in a matter of a quarter of a century, while losing its agricultural character. Buildings would take over its heights, replacing the vineyards - since the mid-1980s - by affordable housing blocks, to solve the insoluble “housing crisis”.

With the construction of the “December 11 neighbourhood”, a low-cost housing complex, urbanisation would expand to reach the edges of the slum. The new generation of inhabitants then gave the neighbourhood a new name, because each generation invents a name for itself. Ironically, the December 11 neighbourhood was chosen as an homage to the 1960 popular mass protests, which have changed the course of the Algerian revolution from amidst the slums that surround the white city: Clos Salembier, The Ravine of the Wild Woman, and Nador… Those were names that had once made history in Algeria, but which have been completely eradicated, as Algerian rulers triumphantly state today, forgetting that those very conditions would result in the very same consequences.

Algiers: A zero-slum capital

“Eradicate the slums” is an old Algerian ambition that has been there since the 1962 Tripoli Charter. Until today, such ambitions haven’t been fulfilled.

Can one, however, eradicate slums without questioning poverty? As these slums endure, a social history unfolds: whenever a shantytown is eradicated, another springs, in its place or right next to it. This has been the case all throughout the periods of colonization, “specific socialism”, and finally the brutal passage to the “market economy” system. All this in a country where the housing policies of the more impoverished people have been truly puzzling, which resulted in unrest and violent action in urban civil spaces. It was like a “metronome” that denoted the distribution of “social” housing by an administration that resorts to the police to re-establish “public order”. In 2007, it was estimated that there were 569 shantytowns in Algiers, representing hundreds of thousands of people.

“Between 2014 and January 2016, the Algiers wilaya managed to eradicate more than 316 slums and rehouse more than 44,000 families” – says a document titled “Algiers, a zero-slum capital”.

Such eradication was intended to be total under the Bouteflika regime. The United Nations and media would be called in to witness the destruction of these houses and the rehousing of its “poor”, amidst praise. But to no avail.

To question shantytowns is to question social inequalities – that is, “the economy of poverty”, as termed by sociologist, urban planning expert, and author of Concrete vs. Tin Cities, Rachid Sidi Boumediene. These topics have become taboos. Sidi Boumediene writes: “The linkages between job creation, income, and raising living standards, which is the backdrop to the war on slums, where misery is amalgamated, have disappeared. They have made way for policies of physically dissolving slums, as part of a housing policy.” He concludes that “Algerian capitalism has managed, in an unspoken manner, to reform – on a different scale – both the formal city and the “popular city”, where slum dwellers live. As such, and once more, these neighbourhoods would be home to local (or indigenous) inhabitants. This has certainly happened at other levels as well but with generally similar results”.

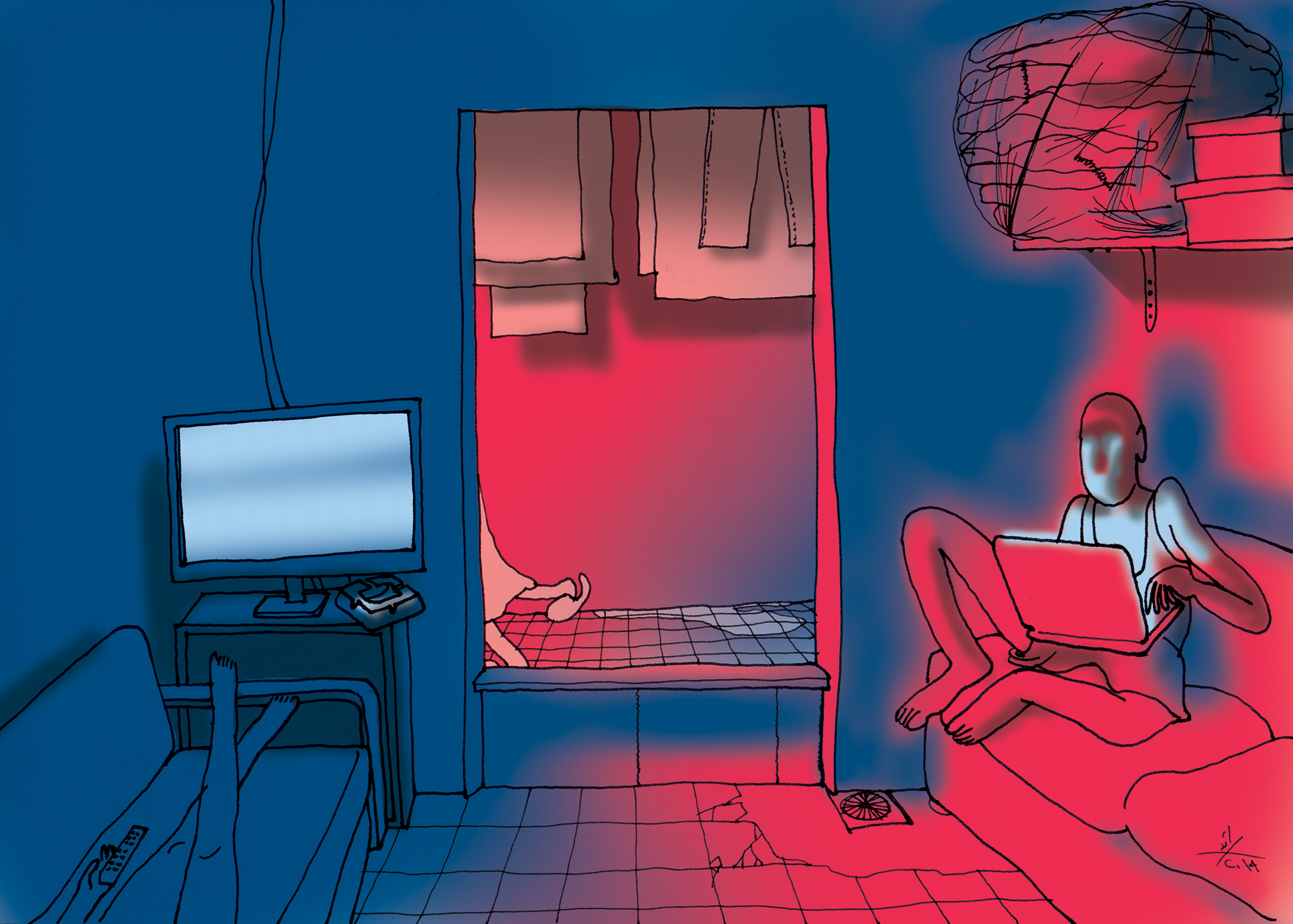

Today, going to Aïn Benien to ask the new inhabitants of this neo-slum area questions would entail discovering how invisibility is a political construct that creates a state of total absence of social security, in addition to poverty.

The December 11 neighbourhood was chosen as an homage to the 1960 popular mass protests, which have changed the course of the Algerian revolution. The names of these slums have once entered history, but have been completely eradicated today, as Algerian rulers have proudly stated.

Tossed into the margins of the world, these inhabitants would never find peace. Today, the decisionmakers of this country – which swings between drained agriculture, an abandoned industry, and diminishing petrol revenues – seek to transform this shantytown into a new “Eldorado”, thanks to the miracle of tourism: “its geographic location, which overlooks the sea […] clearly works to its advantage, and places it on the list of coastal cities with a touristic potential”. This is how a touristic booklet describes the region; all the while, slums are merely mentioned as follows: “Eradicating slums […] is considered a priority strategic objective.”

Listening to the Mountain Sheikh, one of the oldest inhabitants who have lived in this part of the slum following independence, means realising the incredible amount of energy needed to resist objectification and reclaim agency over one’s destiny – through exhausting and inexhaustible strategies. Being made invisible doesn’t stop one from hoping.

The mountain sheikh

The Mountain Sheikh story would have gone down in history as a success story had it not been built on sand.

Wearing his Friday gandoura, the Mountain Sheikh, chatty and full of jokes, welcomes us into his humble living room whose walls were built of sturdy concrete: “In the past, there was nothing here, neither roads, water, nor electricity.”

The Mountain Sheikh, an 80-year-old, takes us on a tour of his property. Originally, this used to be an old crumbling building that the French settlers had abandoned. In 40 years, the Mountain Sheikh transformed it into a real house, with its garden full of fig and pomegranate trees. Around those, his four sons were able to wring from the “beylic” (1) the right to build their own individual houses. These houses are built at the entrance of the slum zone at the hilltop, standing witness to an entire life story.

Gradually, concrete replaced tin, except for the rooftops. The rooms were added accordingly. Time after time, walls would be built, coated with cement, tiled and prepped with masonry. Afterwards, high iron gates would be installed to serve as a fence. Construction never ends, yet the results are incredible. Even the concrete road was paved by the family. “In the past, we used to live like animals, my oldest son can neither read nor write”, unlike his younger sons who received an education; one of whom became a biologist. The sheikh’s house stands out from the others with its white façade facing the sea. The math is quite simple: why buy a piece of land at an exorbitant price when it’s available here for free, and where the city has grown so close?

Algerian capitalism has managed, in an unspoken manner, to reform both the formal city and the “popular city”, where slum dwellers live. This has certainly happened at other scales as well but with generally similar results.

His family does not wish to move to any other place; here it has made a life and invested all its resources, without owning any legal documents to prove the ownership of the property, except for the heaps of receipts of the purchased construction materials, which the sheikh keeps as proof, along with tons of stories about the battles with the gendarmerie about the land boundaries throughout the recurrent censuses that lead to nothing. All it takes is an administrative decision for the bulldozers, accompanied by the gendarmerie, to arrive and erase these people’s past, present, and future. The sheikh talks about the administration with extreme contempt: “I wouldn’t even trust them with a lone sheep’s head”.

From self-management to openness

The sheikh was born in 1939 in the Kabyle mountains, 200 kilometres away from the capital. However, he couldn’t decide to part ways with his miserable life as a landless farmer until 1963. He was 24 then, after which he lived a homeless life between Algiers and the Kabyle region for 14 years. At night, he would sleep in public bathrooms or on a straw bed, while he would offer his services to do hard work during the day. The sheikh says: “I was a simple fellah (farmer), what else could I have done?” He then followed in his uncle’s steps, who managed to “secure an acceptable social situation” in Aïn Benien, and so settled in the area in 1977, accompanied by his wife and sons, whom he summoned from his hometown “driven in a 403 car” (2).

The sheikh’s career entwines with the history of postcolonial agriculture. In 1963, the Mountain Sheikh was part of the unique story of Algerian farmers who controlled the land that the French settlers had occupied, spontaneously creating a “self-management” experiment to guarantee harvest and provide food. While the sheikh survived hunger, he wouldn’t survive poverty.

In 1987, Algeria invented its own opening up economic policy. Lands would then be distributed in the form of “exploitation privileges” with a 40-years expiry limit, given to farmers who would then be left to figure things out on their own and become “investors”. The experiment was a failure. Following ten years of implementation, the lands were given up.

After a while, the self-managed lands disappeared, and, between 1973 and 1982, Colonel Boumediene would turn the self-management experience into an “agricultural revolution”. The sheikh lived that transformation. He would have the right to “cash advances” that equal minimum wages; notably, part of this remuneration would be made in the form of agriproducts. As such, his situation changed; for the first time in his life, he had the right to a pay stub and social security, which he calls “the insurance”.

In 1987, Algeria invented its own opening up economic policy. Following the “agricultural revolution”, a new system of exploiting the public lands that have remained in government hands was instilled. These lands would then be distributed in the form of “exploitation privileges” with a 40-years expiry limit, given to farmers who would then be left to figure things out on their own and become “investors”. The experiment was a failure. Following ten years of implementation, the lands were given up.

The sheikh adapted to this new situation. As agriculture no longer guaranteed their daily bread, the farmers welcomed construction work. The sheikh worked for 18 years as a construction worker, painter, and a salaried worker at a public company specialised in construction. Today, he’s retired and lives off of his retirement salary, which amounts to 19,000 Algerian dinars – the equivalent of around 80 euros a month! A “luxury” that his youngest son might not even enjoy. “Unemployed”, the latter lives off of gigs in the informal sector, servicing pizzas and cybercafés. He doesn’t declare his work or revenues, and receives neither social security nor pay stubs.

Such a situation is a real obstacle to the young man. It prevents him from enjoying the legal measures to obtain social housing, as he has no evidence to prove that he would be capable of paying the needed amounts. This is a double punishment. On the one hand, the son is being exploited by private sector bosses, while public authorities abandon him on the other. As has been the case for his father in the past, the son belongs to a mass of a standby workforce that can be easily and excessively exploited. They live a systematic precariousness that plays into the hands of private businesses; a mass of exploited and scorned workers.

As for the sheikh, an entire life of hard work and labour couldn’t save him – despite everything – from “precarious housing” and poverty, in a country that suffers a shortage of housing, rendering the latter extremely expensive.

From the pickaxe and rope to the counter

His whole life, the sheikh has self-organised to take care of this situation. He fought, like a true strategist, to provide a roof over his family’s head and a minimum of urban comfort: “Here, you must figure it out on your own. We’ve had to provide our own water and electricity”.

At the beginning, the sheikh would depend on spring water to secure potable water: “I’ve used a pickaxe, a rope, and a bucket and dug myself a well. Once, a municipal employee arrived and told me to “destroy” it. I stood up to him and told him that this would never happen. The well still exists today, and I never paid for water.”

It was not until 2001 that the neighbourhood was connected to a public water infrastructure, thanks to a visit from the Minister of Water Resources, accompanied by the mayor. The visit was a veritable event in a region where an extremely violent civil war had just ended (1992-2000), dividing the inhabitants between the “armed Islamic groups” and the “self-defence groups”, which the sheikh joined after the failed authorities armed him. A “war” would, in turn, bring in a new population that had fled the battle zones, which would result in an overpopulation that could no longer live off of spring water. The minister turned to the mayor and asked, as if paying his debts: “Are these humans or not? Then you must find a solution and supply them with water pipes”.

Obliged, the mayor followed orders. He economised, however: one pipe per hundreds of families. “It was chaos. The inhabitants fought night and day. Each wanted to fill up their twenty containers. One night, with the young men’s help -may God protect them- we dug up the earth. With a drill, we connected a pipe to each of our houses,” the sheikh explains. The municipality became aware of this, and attempted to reorganise things. It supplied individual pipes that conformed to standards, while installing meters to calculate water consumption. After years of negotiations, the sheikh agreed to a compromise: he would pay a fixed price for his subscription, but without paying for water, continuing to use “the unofficial pipe”.

The “deal” that regulates matters in Algeria between the social outcasts and the administration stipulates that the poorest Algerians would take what’s left of public property, like small pieces of land and water, as if they were claiming their own share of petrol revenues. In exchange, the state would look away, in order to maintain social peace.

In a state of impressive self-organisation, the sheikh’s family seized for itself, as well as for its neighbours, as one family, and in the same manner, their right to electricity – from an electric tower, set up following the construction of the low-cost housing projects. Faced by facts on the ground, the national power company had no solution left but to install individual electricity counters, to demand payment for the service it was forced to provide.

This meter business was a big deal because water and electricity bills finally enabled those families to get a legal address for the first time in their lives. They now had proof of residence.

To reduce the ambiguous relations between the state and these slum dwellers or to see only their “anarchy” would be to look away from the real “deal” that regulates matters between the social outcasts and the administration in Algeria. The deal stipulates that the poorest Algerians would take what’s left of public property, like small pieces of land and water, as if they were claiming their own share of petrol revenues. In exchange, the state would look away, to maintain social peace.

However, this was an unstable deal. What was given in a twisted way, unrightfully, could also be claimed back in that very same manner. These public lands, “abandoned” so long as they’re considered insignificant, could in reality constitute an extra resource of wealth, that the corrupt employees and the nouveaux riches with “structured projects” could develop. Today, the governor of Algiers who had actively participated in the eradication of slums is serving jail time for charges related to corruption. In the meantime, the Algerian street has been protesting since February 22nd, chanting: “You’ve swallowed up the country, you band of thieves!” However, the marginalisation machine would continue to “eradicate” slums, not because housing would finally become a recognized right, but for the purpose of emptying out lands that can be opened up to all sorts of economic bids.

Behind the dubious friendly appearances, relations between slum dwellers and the police could take an extremely violent turn, leaving both physical and mental scars. Here, the inhabitants recall how only a few months before, the gendarme came with trucks to evict a few dozen families. “A gendarme (policeman) was even hiding to cry”. Ambitions of tourism advance in silence, however. As for the sheikh, he continues to polish the walls of his house. “We never wanted an illegal life. This is God’s land. Had we found a way to a just and legal situation, we wouldn’t have lived like this. Even ministers steal. We’re prepared to buy this land, but they neither want to sell it to us nor give us a place to live. We’ll remain this way, then, suspended.”

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 17/10/2019

1- A Turkish word that comes from the word “bey”, meaning the lands under the prince’s authority.

2- The famous Peugeot 403, emblematic in Maghreb countries.