This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

On March 2nd, 2020, Covid-19 infiltrated Morocco, a country with a health infrastructure barely adequate for basic medical treatments. At the beginning, strict pre-emptive measures were urgently adopted in an aim to contain the Covid-19 virus. To no avail: the coronavirus is a stubborn one and has buckled down to hold out in the country (as it has in the majority of the globe’s countries). No other solution, then but to resort to flexibility that staggers between loose and tightened measures, not to completely eradicate the virus, but to alleviate its spread and intensity, and to tackle it through the logistic, technical, and economic capacities available.

The coronavirus beginnings: tightening, then a gradual loosening

Tightening headlined the first coronavirus days. The authorities assumed a rough pre-emptive and preventive policy, approving quarantines, locking down educational institutions, entertainment, and cafes, and other establishments as early as mid-March 2020.

The Ministry of Health set up hospital wings designated to receive Covid-19 patients in most governmental hospitals all over the country. During that period, the hospital infrastructure was propped with 1,200 ICU beds, 1,500 hospital beds, and 20 laboratories to screen for infections. Regional hospitals (1) were equipped with 23 CT scanners, while the funds allocated to respond to Covid-19 (designated to collect donations and institutional contributions) contributed to purchasing such equipment that cost two billion dirhams (around 200 million USD).

The sanitary lockdown had its upsides, as successively lower cases of infection and death would be recorded. Death rates were very low, limited to zero to ten daily deaths. In the beginning, the sanitary situation was under control; after the Moroccan authorities loosened (2) total lockdown measures starting June 11th, 2020, however, the curve of cases would gradually rise, little by little. The government had no alternative; its financial resources were being depleted in the aftermath of the lockdown. By then, contractors and companies were on the verge of collapse and bankruptcy.

In June 2020, the number of confirmed cases jumped to 563 cases. It peaked on July 31st, with a count of 1,063 coronavirus cases. Its recording coincided with what is termed in the press as the “Night of the Great Escape”. On July 26th, the government announced its decision to ban travel to eight major Moroccan cities in the few days leading up to Eid – and so they travelled in large numbers, that very same night!

The gradual lifting of lockdown (during Stage 3 in late July 2020) resulted in increased daily infections. Notably, the number was on the rise also because lab analyses detecting and recording them were on the rise (from 500 tests during the first lockdown to more than 18 thousand conducted since then). In June 2020, the number of confirmed cases jumped to 563 cases – the highest recorded number of daily cases. It peaked on July 31st, with a count of 1,063 coronavirus cases. Its recording coincided with what is termed in the press as the “Night of the Great Escape”. On July 26th, the government announced its decision to ban Moroccans from travel to eight major Moroccan cities prior to Eid – in an attempt to contain the outbreak during this occasion that boasts of extended family visits, and which would further spread the virus. The “improvised” and “undeliberate” decision the government made, however, had come too late and without sufficient notice to Moroccans. The result was many of them travelling just a few hours before the decision took effect and, thus, set in the dreaded effect: the outbreak of the virus.

“We shan’t sleep in public hospitals”

The rise in coronavirus cases during the summer of 2020 and the months that followed, could be (primarily) explained through the ramifications of the “Night of the Great Escape”. Numbers hit record high during November 2020, with public hospital units filled to the brim.

Before such a scenario, the Ministry of Health had been forced to increase the number of ICU beds, bringing it to three thousand, and equipping hospitals with 1,151 ventilators (426 of which are for emergency rooms). According to the Minister of Health, “hospital unit oxygen usage multiplied by more than 15 times”. To resolve this issue, “medical liquids networks were introduced in twenty hospital centres”, and “nine oxygen tanks were installed in hospitals in Tangier, Marrakech, Oujda, Meknès, Agadir, Beni Mellal, Ourzazate, and Casablanca. Efforts are ongoing to install seven oxygen tanks in seven other hospitals.”

Moroccans benefit from free Covid-19 treatment and hospitalisation in public hospitals. However, an important sector of them say: “we shan’t sleep in public hospitals,” – known for their bad experiences, where previous cases of ill treatment and poor services have been known to take place. In general, these hospitals are not all right; 70 percent (3) of them suffer miserable conditions. The country has 25,385 beds in public hospitals (4), insufficient to contain all patients, as a dip in hospital bed capacities was recorded with the beginning of the Covid-19 outbreak – 1.1 beds per one thousand capita – a much lower number than that recorded in countries with similar GDPs (World Bank).

However, during the first few days of the outbreak, medical treatment was different. Covid-19 cases would be received and accommodated in different places like hotel chains, accompanied by regular medical monitoring. A specialised catering company for the royal palace would provide them with quality food. This only happened, though, after Covid-19 patients exposed the reality of public hospitals on social media, from lack or poor basic services like food and hygiene to the disregard with which they were met by some medical personnel, isolating them in a manner that was described as “unhealthy”.

Later, hospitalisation conditions changed. They became quite worrying, especially for coronavirus patients in critical cases. In that respect, Ja’afar Heikel (5), epidemiologist and deputy chair of the National Health Federation, said that this category of people was setting up ICUs in their homes, with oxygen pumping machines, to avoid treatment in public hospitals. Heikel states: “This is dangerous. These cases should be monitored closely in case respiratory distress arose. Many of them pass away as soon as they arrive in ERs, after it’s too late.”

Moroccans benefit from free Covid-19 treatment and hospitalisation in public hospitals. However, a significant sector of them rejects them for known stories of bad experiences and previous cases of ill treatment and poor services. In general, these hospitals are not all right; 70 percent of them suffer miserable conditions.

Even if Covid-19 patients with serious symptoms were admitted to the hospital early enough, however, they would still face deficient or poor ICU and anaesthesia services, due to shortage of equipment and understaffing. The overall number of ICU specialists is around 200 in public hospitals, doubled in the private sector, with 540 specialists. Anaesthesiologists, on the other hand, are 1,902 doctors and specialists, but are barely present in public hospitals, with a ratio of one per 100 thousand capita. The health system presupposes two nurses for every five ICU patients (6). The World Health Organisation recommends 6 anaesthesiologists as a minimum per 100 thousand capita. However, reality on the ground is nowhere near these recommendations. Personnel are atrociously understaffed in regional hospitals, but also in provinces far away from central cities (Tangier – Rabat – Casablanca).

Such medical understaffing has driven a group of high-income and middle-income Moroccans who needed Covid-19 intensive care to resort to private centres for treatment. These private hospitals took advantage of the critical situation (especially in November 2020), when public establishments were incapable of receiving patients, charging exorbitant prices for treatment, ranging between 60 thousand dirhams (around 6 thousand dollars) and 140 thousand dirhams (around 14 thousand dollars).

Even though Covid-19 is covered by governmental insurance companies (like CNOPS), 90 percent of patients covered by health insurance prefer private sector hospitalisation. Health insurance and social insurance institutions do not reimburse Covid-19 hospitalisation in private hospitals as treatment is ongoing, but rather wait till after it is completed. Therefore, patients who cannot afford treatment are forced to comply with private hospitals conditions, which stipulate handing in cheques as a safety deposit and a prepayment measure, after which they are admitted into the hospital.

Owners of these hospitals, however, justify the rise in prices with the rise in treatment costs, as those can amount to 8 thousand dirhams a day (around 800 dollars), only 5 thousand dirhams (around 500 dollars) of which are allocated to oxygen supplies and the rest to medication, without taking into account the salaries of medical personnel and expenses incurred from buying the protective gear they wear prior to entering ICUs – where patients are hospitalised, and which could amount to 300 dirhams per person.

Solutions: Chloroquine, field hospitals, and home treatments

Morocco applied the “Chloroquine” sanitary protocol, considering it a temporary and practical solution to treat Covid-19 cases. This medical procedure has been adopted since mid-March 2020. This medicine has caused a medical controversy within the country and worldwide. The Minister of Health, epidemiologists, and pharmacists all commended it and perceived it as a temporary alternative to vaccination. Its objectors, however, caution against its sanitary side effects depending on the doses used, like negatively affecting the eyes and heart beats. Regardless of these discussions, preventing a complete loss of control over the sanitary situation was enough reason to adopt the protocol. This solution, despite some of its downsides, contributed to many patients’ recoveries and helped pull the country out from the sanitary crisis – with the least amount of loss. Recovery rates attest to it: 70 to 80 percent of cases.

25,385 beds are available in public hospitals. The overall number of ICU specialists is around 200 in public hospitals, doubled in the private sector, with 540 specialists. Anaesthesiologists, on the other hand, are 1,902 doctors and specialists, but are barely present in public hospitals, with a ratio of barely one per 100 thousand capita.

In parallel with Chloroquine, field (7) hospitals were set up as a concrete step to ease overcrowding in public hospitals. The first was constructed in Casablanca in April 2020, with a capacity of around 700 beds, and began admitting patients with July 2020.

However, because all hospital establishments reached capacity (including field hospitals), the Ministry of Health has been forced, since August 2020, to adopt the “home treatment” protocol, for cases with no visible symptoms or clinical manifestations. Such treatment presupposes lack of risk factors (8) and, most importantly, that the patient be isolated in room with good air circulation. In case living with other people, the latter must leave the house all throughout the isolation period of 14 days. If impossible, they must be put under strict regular medical observation. Applying this measure, however, in low-income groups is met with many obstacles, as many of them have no access to proper housing. Therefore, its application remains dependent on medical follow up efforts rather than authoritarian security monitoring.

“Where’s the doctor?”

“Where’s the doctor?” is perhaps the (customary) question every patient repeats in a public hospital. Patients normally have a hard time locating the doctor and receiving proper treatment from that doctor.

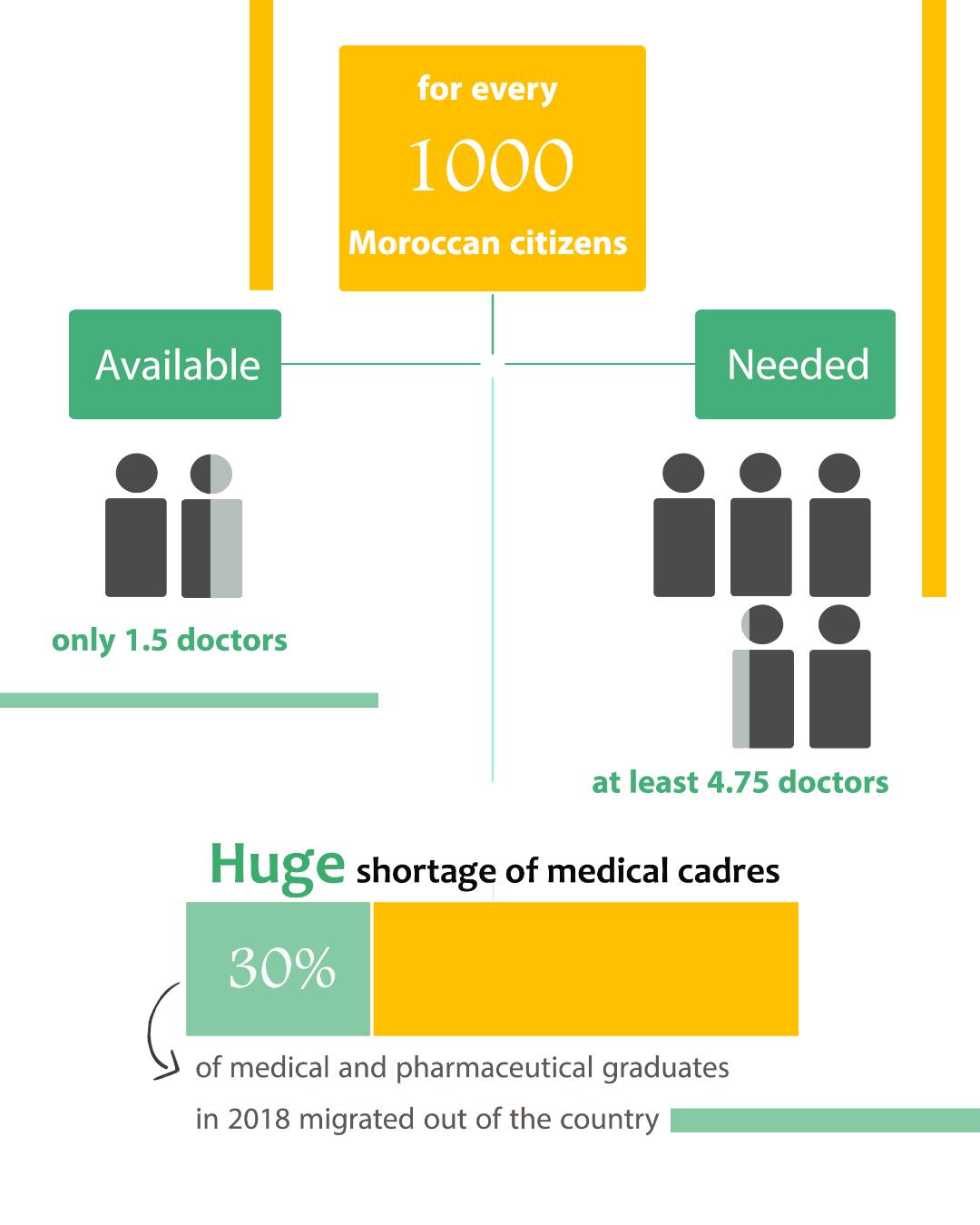

The problem is rooted in understaffing. Statistics stated by the Minister of Health report that the currently available medical personnel do not exceed 1.5 per one thousand capita, noting that the necessary minimum is 4.45. Medical understaffing is estimated at 96 thousand professionals: 32 thousand physicians and 64 thousand paramedics. The government tried to respond to the general demand for medical staff (2019 official statistics) (9) by assigning 5,500 positions in public health, allocated from the employment budget for 2021, increasing the position quota by 1,500, in comparison with 2020. Even though the country has witnessed a slight improvement in the number of medical personnel when compared (10) with 2017, those can hardly meet the conditions required to handle this sanitary crisis.

Public sector doctors in Morocco live off low wages; even with their doctorates, they are paid 7,000 dirhams (around 700 dollars) a month – which equals what employed MA graduates make, and is much less than the very rewarding and tempting salaries their peers in the private sector gain. This category of physicians demands that their remuneration matches the salary index, which means a monthly pay of 1,800 dollars.

Furthermore, public sector doctors face professional and technical issues, as observed in a report prepared in 2020 by the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council. Those include their legal status, to begin with, followed by rough working conditions in treatment centres and hospitals, thirdly, lack of rational human resourcing based on measured performance, and, finally, continuous full-time work. The authors of the report see that these factors contribute to the growing trend of medical brain drain. Perhaps the 603 physicians who had left their country in 2018 alone are the best evidence of such a trend – equalling 30 percent of medical and pharmaceutical graduates of that same year. France alone is home to 7,000 Moroccan physicians (6,510 of whom practice their profession there on a regular basis, and 430 intermittently).

Classist health coverage

Not all Moroccans can benefit equally from health coverage (health insurance). Services are given in a classist manner, in accordance with professional and social sectors. Low-income groups, who suffer from a fragile socioeconomic status, do not necessarily benefit from the obligatory health coverage (AMO) , (11) which guarantees insurance and reimbursement of most treatment and medicinal costs.

This group of people is categorised under the Medical Assistance Regime (RAMED), popularised in the country since 2011, with 16.5 million insured. This regime has its disadvantages, whereby its affiliates do not benefit from a fully covered free treatment; rather, a patient partially contributes to treatment costs in public hospitals. This drives many of them to resort to private sector services and bear the burden of its hospitalisation and treatment costs.

Public sector doctors in Morocco live off low wages; they are paid 7,000 dirhams (around 700 dollars) a month – much less than the very rewarding and tempting salaries their peers in the private sector gain. This category of physicians demands that their remuneration matches the salary index, which means a monthly pay of 1,800 dollars.

Medical brain drain has been growing. Perhaps the 603 physicians who left their country in 2018 alone are the best evidence of such a trend – equalling 30 percent of medical and pharmaceutical graduates of that same year. France alone is home to 7,000 Moroccan physicians.

RAMED is not the only regime with defects, to which many households have no access and which suffers low funding to its offered services. Even the obligatory health insurance coverage enforced by public and private insurance companies alike is prone to problems - like raising the amount of prepayments for treatment while awaiting reimbursement, poor or insufficient refunds offered for an important part of treatments and medication (reimbursement is sometimes less than 50 percent of the overall cost of medication and treatments). However, this health coverage remains celebrated for reimbursing Covid-19 treatment costs incurred in private hospitals, which is not the case for patients subscribed to RAMED, who remain insufficiently covered for diseases.

For many years, nearly 50 percent of Moroccans remained without medical insurance, having to pay for treatment and medication out of pocket. Governmental spending on healthcare is still low, where it has not yet reached the world average, estimated at 10 percent of state budgets. The Moroccan government has been working on increasing such spending, whereby a project of social security was launched, intended to reach a large sector of Moroccans between 2021 and 2023. This project guarantees an obligatory health coverage, for treatment and hospitalisation of an insured 22 million (nearly two thirds of the population) by the end of 2022, with a financial cost of around 1.3 million dollars.

In conclusion…

Morocco’s health system has handled its coronavirus crisis with a mixture of flexibility, strictness, and blunders, amidst a reality that has yet to rise above the level of regression, deterioration, and shortages that the medical establishments and staff have been suffering, along with poor working conditions. Despite adopting a free vaccination campaign (more than 9 million doses had been given by April 30th, 2021) and its significance as a preventive measure, the country’s Covidy conditions are still “worrying”, though not terribly “out of control”. The Moroccan government has lately (been coerced to) paid attention to the significance of this sector by allocating it an unprecedented sum of 20 billion dirhams (around 2 billion dollars) from this year’s budget. This is not enough, however. This sector cannot be medicated, or even supported, on an occasional basis – rather, this is a historical opportunity for Morocco to reassess health policies towards its citizens… and do so perpetually.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 06/05/2021

1)Located in major cities that run the 12 regions of the country, like Rabat, Casablanca, Oujda, Tangier, Marrakech, Fes, Agadir, etc.

2) Lifting lockdown measures was done in stages. Stage 1: Morocco was divided into two zones of loosened measures, based on pandemic severity. Zone 1 received further loosened measures than Zone 2. Later, Stage 2, the authorities adopted flexible sanitary and security measures that changed almost every two weeks, taking into consideration the epidemic status of each zone/region apart.

3)Based on a study conducted by the Moroccan Network for the Right to Health and Life, published in 2017.

4)According to the statistics collected by the High Commission for Planning of Morocco (a national statistics office) in 2019.

5)Ghalia Kadiri, « La hantise de l’hôpital public au Maroc retarde les diagnostics en cas d’infection au Covid-19 », Le Monde.

6)Statistics that anaesthesiologists and ICU specialists of the National Health Federation of ICU Doctors and Anaesthesiologists and the World Health Organisation collected.

7)The Casablanca field hospital cost nearly 45 million dirhams (around 4.5 million dollars), extended over an area of 20,000 m2; other field hospitals were accordingly set up in different cities and areas, like Benslimane and Agadir.

8)Old age, mental disorders, chronic disease, pregnancy, and breastfeeding.

9)11,416 of whom work in the public sector and 13,545 in the private sector, while paramedics (nurses and assistants) numbers reach 31,657 personnel (2019 statistics by the High Commission for Planning of Morocco).

10)Less than one doctor (0.72) per one thousand capita (World Bank statistics).

11)According to the Network for the Right to Health, in 2019, 9 million Moroccans (nearly a third of the population) have benefitted from obligatory health coverage (AMO).