This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

“March... March… March,” the Moroccan football crowds yelled out with gusto, their voices reverberating all over the stadium, in the hope that their national team would secure a winning streak of matches. Indeed, the Moroccan team made significant strides, culminating in its participation in the 2022 Doha World Cup, where the team brought pride not only to Moroccans but also to the peoples of our region and Africa, uniting them in a rare moment of emotional togetherness. Naturally, the Moroccan ultras did not miss the opportunity to attend the matches and support their national team, proudly displaying their banners, tifos, and slogans, and celebrating with heartfelt chants.

However, beyond the euphoria of the World Cup, much was unfolding behind the scenes of Moroccan football, and a lot had changed about its historic patterns. These transformations were influenced by a series of events, decisions, and policies in which the ruling class played a prominent role, taking advantage of the sport for political or other undisclosed goals.

A historical glance

There are conflicting accounts regarding how Moroccans have historically engaged in football’s organized frameworks. One narrative suggests that Moroccans were introduced to the game in the mid-19th century by English sailors, who used to play the game to pass the time while waiting for their ships to be repaired in Moroccan ports. Another account argues that football had, in fact, arrived in Morocco through French soldiers and colonizers.

Several sources indicate that the year 1916 marked the first match between local teams in an organized Moroccan league. However, local media sources suggest that the first official match on Moroccan soil took place in 1913 in the village of Ain Taoujtat between the cities of Fez and Meknes in central Morocco.

On the other hand, the establishment of the very first Moroccan clubs dates back to 1937, when General Charles Noguès, the French Resident-General, approved the creation of the Wydad Casablanca Club for water polo, a project suggested by Mohamed and Abdellatif Benjelloun. As the French Protectorate years lapsed, this national club garnered immense popularity and enjoyed the wide support of Moroccans. Subsequently, several of Morocco’s greatest teams were also established, including Maghreb de Fès (1946), Kawkab Marrakech (1946), and Raja Casablanca (1949).

Founding these clubs became a weapon employed by the national resistance to combat colonialism and mobilize Moroccans through the discourse that pushed the idea that football was far more than a game played for fun; it served as a framework for bolstering national spirit. Victories of Moroccan teams over Europeans teams thus held symbolic significance as wins over colonialism itself, as was the case when the Wydad Casablanca, the largest Moroccan club with local players, won the 1948 championship title.

In the post-colonial period, the late King Hassan II was influenced by the Spanish experience and General Franco's patronage of the Spanish sports teams to divert the population's attention from their pressing concerns. Sports, including football, were no longer solely the people’s domain of action, but also became of great interest to the ruling authority. Therefore, the government sought to foster, support, and finance football as a means of upholding its own influence.

Morocco: A Kingdom of Rent

18-04-2022

Morocco: Who Owns the Land?

01-11-2022

During 1986, the Moroccan national team reached its first historic milestone in football by becoming the first Arab and African national team to qualify for the World Cup playoffs in Mexico. The red and green team faced some of football's best teams in the world, piquing the attention of many, including that of the late King Hassan II of Morocco, who began to view football as a means to rebrand Morocco. Through successful sporting achievements, the king aimed to present an image of a prosperous Morocco, despite the tough circumstances the country was facing at the time. Internally, Morocco was grappling with political conflicts such as military coup attempts, opposition from leftist forces, popular protests, violent repression, and widespread arrests and imprisonment, and regionally, the country was in the middle of the "sand war" with Algeria, all while corruption, autocracy, and various social and economic dilemmas remained rampant.

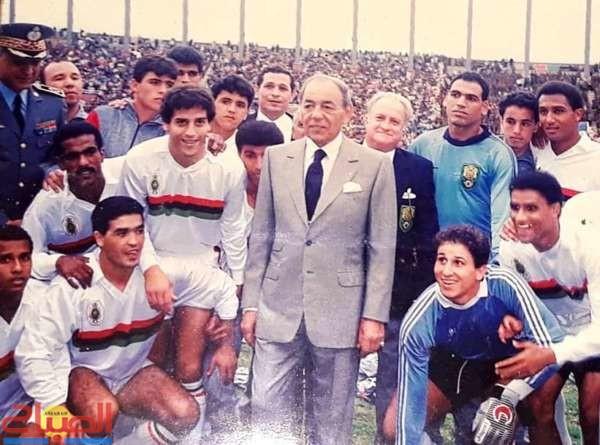

The ruling class became increasingly interested in football. A football victory was seen as a triumph for the king who missed no opportunity to host footballers and take pictures with them in traditional coronation ceremonies.

The national resistance utilized the establishment of the Wydad Casablanca Club and others as a means to confront colonialism and mobilize the Moroccan population. Speeches were given emphasizing that football served a greater purpose than mere entertainment; it was a way to strengthen national unity and achieve moral victories over clubs from European-majority countries at the time. In 1948, Wydad won the championship, further solidifying its reigning position.

National resistance employed the newly founded teams to combat colonialism and mobilize Moroccans through the discourse that football was far more than a game. It served as a framework for strengthening national spirit. Victories of Moroccan teams over Europeans teams held symbolic significance as triumphs over colonialism itself.

The king’s special attention to football became a “focal point in the management of the sports sector, from which sprung all the major administrative decisions of sporting federations (1).” The late King was keen on giving technical directives to Guy Cluseau, French coach of the Royal Armed Forces team, which was founded by the King himself. On August 26, 1962, and regarding a match between the Army Forces Club and Real Madrid within the Mohamed V Cup, King Hassan II wrote to Cluseau in French (2): “Perfect, that's good, we're not ridiculous. Mokhtatif is a big clumsy guy. Make sure to place Mustapha as the center attacking midfield… Apply the support play.”

Towards for-profit clubs

In recent years, the ruling authorities have refrained from interfering openly and directly in the management of some clubs, as had happened with the Royal Armed Forces Club during the 1960s. For many decades, football clubs have been run as sports associations, organized by internal regulations within an office that manages the club’s objectives, incomes, and expenses. This office also organizes the general assemblies, the highest administrative board in charge of electing and determining all cadres.

Football in Egypt: Where People Find Solace

08-06-2023

Football in Iraq: A Game of People and Politics

02-06-2023

However, football clubs are no longer necessarily classified as sports associations, as new efforts emerged to transform them into sports companies based on the provisions of Law No. 30.09, which states that “a sports association can carry out the process of shareholding its assets and credits, in part or in whole, in a sports company.” This law applies to 16 professional league teams and 8 second division teams. Most of the clubs thus developed their institutional and financial models with the aim of transferring their ownership from associations to companies within the deadline of June 30, 2023.

Nevertheless, this law did not bring associations to an end. Rather, the process resembles a delegation of responsibilities, meaning the association entrusts the newly founded company with the managerial tasks. The law specifies that the association must hold a minimum of 30% of the company's shares and possess at least 30% of the voting rights (3).

During 1986, the Moroccan national team reached a historic milestone in football by becoming the first Arab and African national team to qualify for the World Cup playoffs in Mexico. The team faced some of football's greatest teams in the world, piquing the attention of the late King Hassan II of Morocco, who began to view football as a means to rebrand Morocco.

This transitional move was justified as a means for local football clubs to cross from the realm of amateur sports to that of professional sports, and to transform the sport into an economic market for investors who possess the power to “revitalize” it and pump in new resources for its development. Contrastingly, in the past few decades, football has relied almost completely on government and local support. Approximately 1.7 billion dirhams in public funding were granted by the Moroccan Football Federation to clubs in the first division or the Premier League during the 2018-2019 season. Moreover, television broadcasting is considered one of the main sources of income for football clubs, and Law 30-09 stipulates that “50% of these revenues are distributed in a cooperative manner.”

Football experts believe that the process of transforming clubs into companies will effectively eliminate the reliance on a single individual, such as a club’s president, for the club’s financial management. Many of the financial crises faced by these clubs is caused by the inadequate management of specific individuals or by “tying a club’s financial situation to that of one person.”

However, it seems that this transition was rendered a formality after it failed to adhere to the required conditions. Three years after the law was issued, investors are still reluctant to spend their money on local football teams. Distributing the profits of television broadcasting also posed a problem, as the Royal Moroccan Football Federation is responsible to the allocation of funds to clubs according to merit, which the federation has failed to do. Broadcasting revenues are practically still completely distributed in a cooperative manner. Consequently, “it is a bad deal for investors to invest in a major club, because a club that attracts millions of views will benefit from the same broadcasting revenues as small clubs supported by only a few dozens or hundreds of people (4).”

Not “hooligans”…

Moroccan football clubs, with all their legal and financial structures, cannot survive in isolation from the non-institutionalized groups of ultras, who provide the teams with vital moral support during matches. However, these groups are often “exploited by the clubs’ managements as pawns in internal disputes (5).” This triggers violent clashes among fans in the stands, accompanied by vandalizing public and private property and physical violence that may lead to serious injuries or even death.

It is very important to note that not all ultras groups fit the negative stereotype perpetuated by the local media. Some football experts argue that these ultra-fans are not hooligans, and they are not entirely comprised of students, unemployed youth, or wage laborers. In fact, these fans are in many ways distinct from the “hooligan culture” associated with English football teams, whose actions do not reflect social or political objections. In fact, some ultras organizations engage in activities beyond football, such as charitable action in underprivileged and remote villages and participating in blood donation campaigns.

Currently, there are numerous ultras groups in Morocco. Their establishment dates back to 2005. Among the most notable groups are the ASFAR Ultras who support the Royal Armed Forces, the Ultras Green Boys who support Raja Casablanca, and the Ultras Winners who support Wydad Casablanca.

Moroccan football clubs, with their legal and financial structures, cannot survive in isolation from the non-institutionalized ultras groups. These fans are in many ways distinct from the “hooligan culture” associated with English football teams, whose actions do not reflect social or political stances.

Ultra groups do not comply with set laws and regulations. Although these entities may structurally resemble a disarrayed pile of stones, their members are closely knit and coherent. They dedicate their time, support, and unconditional loyalty to their clubs.

Ultras fans are estimated at one million persons. They are organized into small working groups called “Top Toys”. Each of them is assigned a specific task, such as designing and choreographing creative banners known as tifos, managing the cheers and chants in the stands, overseeing the group's funding sources, and organizing excursions to attend their teams’ matches in various regions.

Ultras groups often reject financial support from external entities. Their income comes from member contributions and merch sales. Ultra fans are given membership cards (although the procedure is not official and is neither recognized by the authorities nor regulated by legislation), which guarantee additional financial incomes through a subscription fee determined by each group.

Ultras adhere to four key principles to determine whether a group of football supporters qualifies as an ultras group.

1- Irrespective of the outcome, ultras must continue to chant and cheer for their team during matches. Their chants must be loud and powerful, often accompanied by symbols and gestures aimed at intimidating opponents and retorting insults. A designated leader, known as the “Capo”, is responsible for determining slogans, chants, songs, and their timings, and organizing visual displays such as coordinated hand movements and tifos. The Capo positions himself the higher stands where he can be seen and heard by the rest of the ultras.

2- Ultra fans must not sit during matches; they are in the stands to cheer and support with unmatched enthusiasm, not to sit back and watch like a regular spectator.

3- They must prove an unwavering commitment to attending all matches, both home and away, regardless of the expenses and distances involved. Ultras employ mobilization tactics to travel to matches outside their club's city in affordable transportation. They also organize processions, known as “cortèges,” where members march together before their team’s matches. This display is meant to show the media the club’s strength, popularity, and the passionate dedication of the fan base that is ready to stand by their team anywhere and at any cost.

4- Loyalty to their zones in the stands. The ultras choose their seats away from the regular football supporters. They usually pick the cheapest seats in the third zone, dubbed the “Curva”, an Italian word that means the curve. The zone becomes home for all their acts of support, where they raise their logo which displays their name and symbolizes their “honor”.

Ultra groups do not comply with set laws and regulations. These non-institutionalized entities may structurally resemble a disarrayed pile of stones, yet their members are closely knit and coherent. They dedicate their time, support, and unconditional loyalty to their clubs, providing their players with a dynamic and interactive environment where they can freely and unhesitantly take initiative and make progress. This system fuels the enthusiasm of young members, strengthening their capacity to seamlessly assimilate in the ultras community. Here, individualism is nonexistent, and the key principles are self-denial, community, and loyalty.

Ultra groups are organized in form and identity, but they refuse institutional structures, which makes them difficult to contain by the security and political authorities. These authorities have made numerous attempts to restrict ultras’ activities through legislation (Law 09-09 on combating stadium riots) and physical violence, sometimes with the help of law and other times through a policy of “carrot and stick”. However, all of these efforts proved futile. It was only in recent years, when the ultras were banned from entering the stadiums, that the authorities realized the irreplaceable influence and significance of the ultras presence in the now empty, lifeless stands.

Chants: more than cheers

Ultras movements continually seek ways to resist the undeclared war the authorities have waged against them. One of those ways is chants. The song “Fi Bladi Dalmouni” (They have wronged me in my own country), which was chanted by the Ultras Eagles in support of Raja Casablanca in 2017, shot Moroccan ultras to fame. The song became the hottest topic of discussion in the country because it touched on the authorities’ attempts to control and subjugate the activities of ultras under the pretext of fighting riots, or the activities which the ultras refer to as “zero fear”.

“Fi Bladi Dalmouni” (“They have wronged me in my own country”), a chant by the Ultras Eagles in support of Raja Casablanca

This chant describes the security and political authorities in the country as unjust, while portraying the ultras and football supporters as the oppressed. Speaking in the second person plural, the song addresses all those in positions of authority on behalf of all those people who live in miserable conditions in their country, highlighting their hardships through a lexicon of oppression, injustice, and deprivation (6).

“This is the country of Hokra (contempt)” by the supporters of Ittihad Tanger

The chants and songs of the ultras address an unnamed “other”, often the referring to political or security authorities who unleash symbolic and material violence against an oppressed population. This sentiment is conveyed in lyrics such as: “You didn't want us to receive an education, you didn't want us to work, and you didn't want us to be aware of what’s going on… You drugged us with Valium and abandoned us… We were orphaned in our own country.”

“Fi Bladi Dalmouni” is a song that describes the authorities as unjust, while portraying the ultras and football supporters as the oppressed. Speaking in second person plural, the song addresses all those in positions of authority on behalf of all those people who live in misery in their country.

The solidarity of the ultras extends to other nations that hold a special emotional significance in Moroccans’ collective consciousness, including the Palestinian cause. The Ultras Los Matadores have raised tifos and arranged solidarity vigils in one of the squares of Tetouan in support of Palestine, as did the Ultras Winners.

The songs and chants of the ultras (7) are rife with meanings of resilience (“We shall not give up”) and feelings of oppression (“Who will heed our grievances?”; “We are the oppressed ”) (8). Other lyrics demonstrate a challenging political stance that opposes the security and political authorities (“We are here to stand in the face of the government”; “I refuse to do compulsory military service ”)…(9)

The language of protest intensifies in the song “Voice of the People” performed by the Ultras Winners: “The freedom which we have always desired, my Lord... Freedom soothes my aching heart!” The word freedom becomes a recurring mantra in the song. It is the ultimate, unattainable demand, one which the authorities hinder with their laws and oppressive practices that view the ultras as “ignorant adolescents”, while pushing them to remain “slaves to the status quo,” according to the song.

Allies of the oppressed

Ultra groups produce political and social discourses that are in line with the public’s pressing demands and concerns. They have repeatedly supported the demands of the regional movements that erupted in the forgotten peripheral areas of Morocco and defended the cause of the contract teachers. In response to the violent oppression of the teachers’ protests in the street, Ultras Red Men, supporters of AS Meknassi, have carried a banner that read “A country that offends its teachers cannot progress.”

Ultras Red Men have also released a statement expressing their support for the teachers who were demanding secure jobs in public schools. “In this era of freedom, renaissance, and human rights, teachers are subjected to police brutality, despite their difficult circumstances, and in violation of their right to protest. They are met with violence, including physical assault and harassment of both men and women,” the statement said.

The solidarity of the Moroccan ultras extends beyond national boundaries, to other nations that hold a special emotional significance within the local collective consciousness, including the Palestinian cause. The Ultras Los Matadores, known for supporting Moghreb Tetouan (a team from Northern Morocco), have raised tifos and arranged solidarity vigils in one of the squares of Tetouan in support of Palestine.

Along the same lines, the Ultras Winners wasted no time in responding to the United States’ declaration recognizing Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. The Winners released a statement asserting that, irrespective of any international declarations and desires, “Jerusalem remains the capital of Palestine. Their statement proclaimed, “Palestine is the greatest of our causes and the ultimate victory we eagerly await.” Their banner in the stands sent a strong message to the political parties that agreed to the normalization of relations with Israel in late 2020, stating, “You have accepted normalization, but they have not accepted you.”

In conclusion

The ultras were born out of a desire to rebel against political and security authorities, their policies, discourses, and the material and symbolic capitals they possess. The ultras perceive the authorities as adversaries, in contrast to their relationship with the general population, who consider the ultras as allies in their fight for justice and demanding solutions for their complex and lingering issues. Consequently, these non-institutional groups have emerged as alternatives to intermediary institutions like political parties and unions. Through their chants, songs, and unwavering solidarity, the ultras do not shy away from making their voices heard, offering support whenever and wherever they can, be it on public buses, stadium stands, or protest squares everywhere across the nation.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 23/05/2023

1- From an interview with sports expert Moncef Al-Yazghi

2- His exact words in French were: “Parfait, it's bon, on n'est pas ridicules, Mokhtatif is 1 (un) gros balourd, touchez de mettre Mustapha l'avant-centre….appliquer le jeu de soutien.”

3- According to sports expert Moncef Al-Yazghi in his report to SNRT News website.

4- According to a statement by the expert in football refereeing, Abd al-Rahim Gharib, to Eqtisad.com

5- As stated by sports expert, Moncef Al-Yazghi

6- For more information, see Hassan Al-Taweel's study, “The Discourse of Protest in Ultras Chants... A Rhetorical Reading.”

7- For more information, see the study by Said Bennis, Professor of Social Sciences, “Representations of the Protest Discourse of the Ultras in Morocco and their Political Effects.”

8- Lyrics from a song performed by the Ultras Dos Kallas for the Difaa Hassani El-Jadidi team, a Moroccan football club in the city of El-Jadida in West Morocco.

9- Lyrics of the song “Fi Bladi Dalmouni”