This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The land is multi-dimensional. Besides its being the reservoir of natural resources like water and minerals, the stage of the environment, and the bearer of food, it constitutes, at the same time, a human identity, a sense of belonging, a refuge, and a cultural heritage. In addition to the common history, language, religious and ideological values, land is one of the main constituents of the being of the nation. Man cannot live without being connected to the land, owning the right to exploit it, earning a living from it, and realizing one’s identity above it.

Land is the cornerstone

From the earliest stages of man’s existence on earth up until today, land, as well as defending it, has constituted the fundamental preoccupation of nations to confirm their identities, establish their freedom, and preserve their means of living. It has also been the vehicle that the oppressors used throughout history to practice their tyranny and exploitation. This applies to all the resistance movements against occupations old and new, such as the Palestinian Resistance, as well as all the social rights movements the world has known, whose aim was to defend the right of using the land and distributing its goods. These movements include the Landless Workers' Movement in Brazil, Chile, and Argentina, the indigenous tribal movement in Northeast India that fought to retrieve the lands the population had been forcibly evicted from to build a dam, the Oulad Khalifa uprising in Morocco, and currently the Akal Movement in the Souss-Massa region, to list but a few. Moreover, the struggle for land will continue as long as occupation, exploitation, and tyranny exist. The land also constitutes a fundamental element of class struggle. In this respect, we can recall the Moroccan tribes in Atlas, Rif, and Souss that fought heroically against colonialism for freedom and land. The revolution of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi is a distinct testament to this struggle.

Morocco: A Kingdom of Rent

18-04-2022

As for our country, we have to continue to struggle for the recognition of the right to own land for those who work in it. We should also struggle to ensure that Moroccan law is consistent with international law, especially concerning the articles that deal with the exploitation of land and natural resources, as well as giving back the land that was retrieved from the colonial power to its original owners.

The land has always been a colonial vehicle to subjugate nations. It has also been a fundamental element employed by the dominating and exploiting classes (of all forms including feudalists, compradors, big bourgeoisie, and state officials) to impose their exploitation and possession of the fruit of the land at the expense of the hardworking farmers, agricultural workers, villagers, and tribes people. The dominating class can evict an entire tribe to build a dam or to establish a big agricultural project. One such example is the Adarouch Ranch, a private modern company for raising imported cows to produce meat, owned by a Moroccan tycoon. It lies in the region of Meknes and occupies thousands of hectares that have been evacuated from their rightful owners.

Obligatory registration of the communal lands

Right after Morocco’s colonization in 1912, the colonialist powers were able, in partnership and with the collusion of feudalism and major leaders, to seize the land collectively exploited by the Berber tribes (as communal land constituted the bulk of agricultural land) and impose the law of ownership and registration. This was the beginning of the descent of most of the Moroccan regions into marginalization and impoverishment, especially those of the Berbers who fiercely fought the advancement of the colonial forces on national soil and resisted occupation. Their marginalization is ongoing, since the land was never returned to its rightful owners after the settlers left. Moreover, the adopted agricultural policies were dedicated primarily to serving major real-estate holders, marginalizing small farmers, and establishing the authority of our country’s dependent capitalist regime by directing the agricultural products towards imports instead of being concerned with securing the Moroccan people's food sovereignty. This trend became clear after announcing the State’s new policy, embodied in the Green Morocco Plan. The plan places, in the State’s name and under its guardianship, the major elements of production (land, capital, and water) in the hands of the agricultural capitalists and a few major landlords. It also integrates the handful of farmers who have the resources and can comply with the requirements, while the rest of the industrious agricultural workers, who number more than one million, remain uncovered.

To approach the issue of land in Morocco, it is necessary to address, on the one hand, the lands that the state managed after being retrieved from colonialism through public companies, namely the Agricultural Development Company (Sodea) and the Management Society of Agricultural Areas (Sogeta). On the other hand, it examines the communal lands or the lands of the tribes that are still the subject of intense political debate in Morocco, as they are intended to be part of the ongoing process of privatization.

Lands retrieved from colonialism

To understand the origin of the lands of the Agricultural Development Company (Sodea) and the Management Society of Agricultural Areas (Sogeta), how they were established, and their initial area, it is necessary to find out the course that these lands, which were retrieved from the settlers, took to reach the state they are in today.

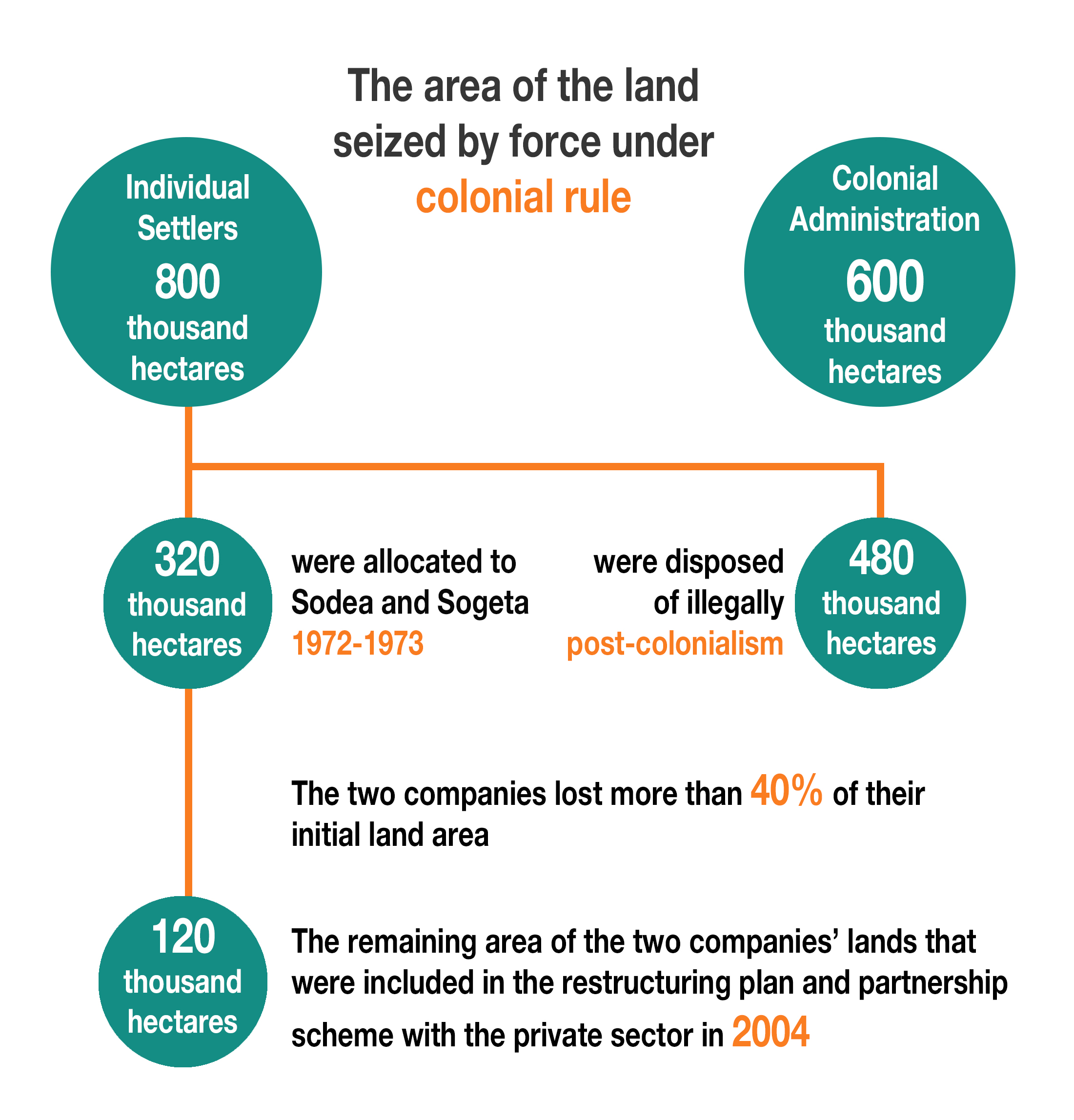

It is known that the lands that were run by the two companies Sodea and Sogeta were originally Moroccan farmers’ lands that were seized by force during the colonial period. The area of these lands, which are among the most productive arable lands in Morocco, exceeded one million hectares. These lands were dispossessed from their original owners, either by the official colonial administration or through usurpation by individual settlers.

At the beginning of the 1970s, 320 thousand hectares of the settlers’ lands were retrieved within the framework of the Morocconization law, and the management of this area was temporarily entrusted to the two public companies, Sodea and Sogeta, while the fate of hundreds of thousands of other hectares that “disappeared “in mysterious circumstances was not known.

The lands that were run by the two companies Sodea and Sogeta were originally Moroccan farmers’ lands that were seized by force during the colonial period. The areas of these lands, which are among the most productive arable lands in Morocco, exceeded one million hectares.

Those who benefited from land distribution are the notables, the rich and powerful companies such as Agricultural Properties or Zniber, and the foreign companies. As for the agricultural workers, farmers, technicians, agricultural engineers, and the unemployed, they were not even allocated a few hectares of the lands that were the property of the people in the first place, before the colonialists usurped them.

Numerically speaking, the settlers seized one million and 215 thousand hectares that were later retrieved between 1964 and 1966. Of these, 500 to 600 thousand hectares were distributed to official colonial administration, 700 to 800 thousand hectares were given to individual settlers, and 320 thousand hectares were entrusted to Sodea and Sogeta. As for the remaining part, which constitutes the largest area, it was disposed of in ambiguous and unlawful ways.

The two companies, Sodea and Sogeta, were launched in 1972/1973, with an area of 320 thousand hectares, from which the agrarian reform process benefited by about 90 thousand hectares. Over the following three decades, the two companies lost more than 40% of the area they initially had when they set out. The plundering that these lands were subjected to left only 120 thousand hectares, which is the area that was included by the restructuring plan or the so-called partnership with the private sector that began in 2004 through leasing property for a period ranging between 17 and 44 years subject to extension or privatization.

The "Gloomy" Economy of Morocco

15-07-2019

Those who benefited from the land distributions, whether in the first or second phase, are the notables, the powerful, and the rich - be they politicians, parliamentarians, princes, or powerful companies such as Agricultural Properties, Zniber, and foreign French, Spanish, Emirati, and Russian companies. As for the farmers, the agricultural workers, the technicians, the agricultural engineers, and the unemployed, they were not even allocated a few hectares of the lands that were the property of the people in the first place, before the colonialists usurped them.

One of the farms of the Rummani region was leased in the framework of the second phase of the concession process to a company whose shareholders included the sons of a settler who used to exploit that farm before it was allocated to the Management Society of Agricultural Areas, Sogeta. The farm used to be owned by Al-Bashiriyyin, a family that fought the French colonial forces, along with Hammou Zayani who won the battle of El-Herri in the Middle Atlas in 1914 and became a Moroccan legend. The same thing happened in a farm in the Berkane region, which was also leased to a son of a settler who used to exploit it during colonial times.

The Green Morocco Plan

The concession of agricultural land to the state is one of the main pillars on which the Moroccan agricultural strategy, dubbed The Green Morocco Plan, was founded. The government decided to abandon the land it used to exploit through Sodea and Sogeta and lease it instead for extended periods to major holders and Moroccan and foreign investors to create agro-industrial complexes that were accompanied by generous aid from the Agricultural Development Fund. This concession proved to have several flaws including:

- The lack of a clear vision of the partnership: The State did not define beforehand the tasks that a partnership entails in the context of its role in serving its agricultural development strategy, in addition to the multiplicity of those involved in the process and the laws. Furthermore, there was a decrease in the lease rate to about 800 to 1000 dirhams per hectare at a time when its market rate was 5000 to 6000 dirhams.

- The partnership was not anchored towards the fundamental crops that are associated with food sovereignty. Moreover, contrary to what was agreed on, seeds were not produced and the state abandoned 400 thousand hectares that were outside the scope of the partnership.

- The agricultural workers and farmers with limited capabilities were excluded from taking part in the partnership. The data of the second phase in which 500 thousand hectares were conceded shows that the big land estate holders who were not necessarily professionals benefited from 50% of the conceded areas while the agricultural companies benefited from 25%, compared to 15% by foreign companies and 10% by politicians and parliamentarians.

- The layoffs and underinvestment.

Communal or tribal land

The communal land system in Morocco was founded (1) and consolidated throughout the country’s long history. It encompasses about a third of the Moroccan population who live on a significant land reserve whose area is greater than a third of all agricultural, grazing, and forest land in Morocco.

The total area of the communal land is about 15 million hectares, 85% of which are grazing lands and the rest are forest and arable lands of about 1.5 million hectares. More than 13 million people, which is about a third of the country’s population live on the resources of these lands. They constitute 2.6 million families that are divided among 4563 tribal branches. These official statistics are more than ten years old and they are certainly subject to escalate as a result of demographic growth. The collectively cultivated lands are considerable, as they compose 16% of the total Moroccan arable lands. They are exploited by 902 thousand of people at a rate of 1.7 hectares per person.

The mode of exploiting these lands has led to the deterioration of the crucial real estate heritage of the tribes while the demographic growth led to complicating legislation. Furthermore, the area of these lands was reduced, as some of them became privately owned since they were subject, as of the era of the foreign protectorate, to plunder, monopoly, fraudulent sale to third parties, seizure by force, and the leasing of large areas for nominal prices.

After independence, the lands were retrieved and redistributed within the framework of the land reclamation program, which the two state companies Sodea and Sogeta were a part of. Most lands were distributed and the lands of the two companies were conceded to investors and major landlords who do not belong to the tribes.

A big part of the wealth-producing land is now communal or tribal, whether through agricultural exploitation or through real estate speculation, and a significant part of it is irrigated land that can generate tremendous profits if invested. Moreover, a number of these lands are located inside the urban areas, and as such, have turned into hot spots for real estate speculation, an easy source of wealth and profit.

The arable lands of the tribes who constitute a third of the Moroccan population are considered significant as they compose 16% of the total Moroccan arable lands. They are exploited by 902 thousand people at a rate of 1.7 hectares per person.

The communal lands are governed by laws that were enacted one century ago. The French colonizer founded the Guardianship Council by a decree (2) issued on April 19, 1919. The Council’s task was to monitor all operations relevant to the communal lands. This council was presided over by the Director of the Interior.

After independence, the same decree was observed after the Minister of the Interior replaced the Director of the Interior. This decree provides articles that organize and manage communal life, including appointing their parliamentary and litigation representatives and resolving inter-tribal conflicts. It also provides some articles that organize the exploitation process, whether direct exploitation or through leasing or concession to the state, local groups, public institutions, and others. It is clear that maintaining this colonial decree aims to control these lands, except for the issuing the Agricultural Investment Code in 1969 that addressed the ownership of communal lands of the irrigated sphere, which was limited to distributing 200 thousand hectares of irrigated lands to the rights holders, after dividing the land into parts.

As for the unirrigated communal lands which constitute 87% of the agricultural lands, as well as vast grazing and forest lands, there has not been any measure regarding them to date. The accomplishments so far are extremely modest, as only 300 thousand hectares of land have been registered, which is only 2%, although more than 6.1 million hectares had applied for registration.

The mode of communal land management is based on tradition, as well as practicing gender discrimination by excluding the women (the Sulaliyyates) from the right to exploit land or to transfer this right. Women are thrown out of their lands and denied the right of being right holders, which perpetuates their poverty and forces them to migrate. To confront this injustice against the tribes’ women and their deprivation of the rights of benefiting from the lands of their ancestors, a woman protest movement was launched and reached its peak in 2009, which impelled the Minister of the Interior to announce women’s right equal compensations.

With expansion of the protest movement, with both men and women raising their voices against injustice, the issue of the tribal and communal lands was transformed in the last few years into a legal rights issue that was adopted by several human rights organizations. Today, several rights committees are active in the regions that witness conflicts related to tribal “Sulaliyya” lands, to support the struggles of the rights holders.

The mode of communal land management is based on tradition, as well as practicing gender discrimination by excluding women from the right to land. This perpetuates women’s poverty and forces them to migrate. A woman protest movement was then launched, peaking in 2009, which impelled the authorities to recognize this right.

The state is still looking for a way out of the problem of the communal land between the escalation of the rights holders' protests and the objective of privatizing these lands under slogans of investment and raising productivity.

Finding solutions to this system’s issues begins with considering the following:

• Establishing an independent national authority for the management of communal lands in which all concerned parties democratically participate, and removing the matter from the hands of the Ministry of the Interior.

• Reviewing the laws that govern the communal lands, pertaining to organization, management, and exploitation, to secure the rights of the rights holders.

• Enacting just and clear laws to determine those of the tribe members who have the right to transfer the right of exploitation.

• Enacting a clear law to appoint the parliamentary representatives of the tribes and define their tasks, terms, and how to compensate or dismiss them if need be.

• Abandoning traditional laws and replacing them with modern and just laws that secure the right of women to benefit from the communal lands.

• Drawing practical plans to enable the rights holders to own these lands and limit the fraud of the major sponsors and real estate speculators.

In conclusion, the report entitled Fifty Years of Human Development and Prospects in Morocco for 2025 (3) asserts that there is a minority of farmers who own significant areas of agricultural land in Morocco. Less than 1000 landowners and investors exploit about 500 thousand hectares (120 hectares of which are irrigated in a modern manner), equivalent to 9% of the total arable land and 15% of the total irrigated land. According to the report, 100 holders of those own one-quarter of the imported cows and sheep, which enjoy the most modern ways of breeding. This sector is mainly export-oriented and relies on wage labor.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Ghassan Rimlawi

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 02/05/2019

1- These groups are defined as tribes, tribal clans, Dawawir (tribal circles), and Sulaliyya (dynastic tribes), and they enjoy legal status and moral character. They are subject to private law and they have their own legislative and organizational law. The tribes are under the guardianship of the Ministry of the Interior in Morocco.

2- All kinds of decrees, including royal ones.

3- http://www.ires.ma/ar/50-ans-de-developpement-humain-maroc-perspectives