This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

While Morocco has no petrol or natural gas, it has 3500 km of fish-rich coastlines. Furthermore, it has important natural resources of huge phosphate reserves, precious metals extraction and exploitation sites, deep-sea fishing, and innumerable sand quarries. The Moroccan kingdom is replete with natural resources, that come with economic, as well as political, stakes.

Ever since Morocco’s independence in 1956, the distribution, management, and exploitation of these resources has been the subject of repeated debates, questioning, and controversy – as they lack any legal framework that relies on rational and consensus-based texts. What’s the nature of these resources, though, and what economic weight does it have? How are they used? Who are the actual beneficiaries? And what legal framework determines the pathway of distributing and managing these resources?

A colonial heritage

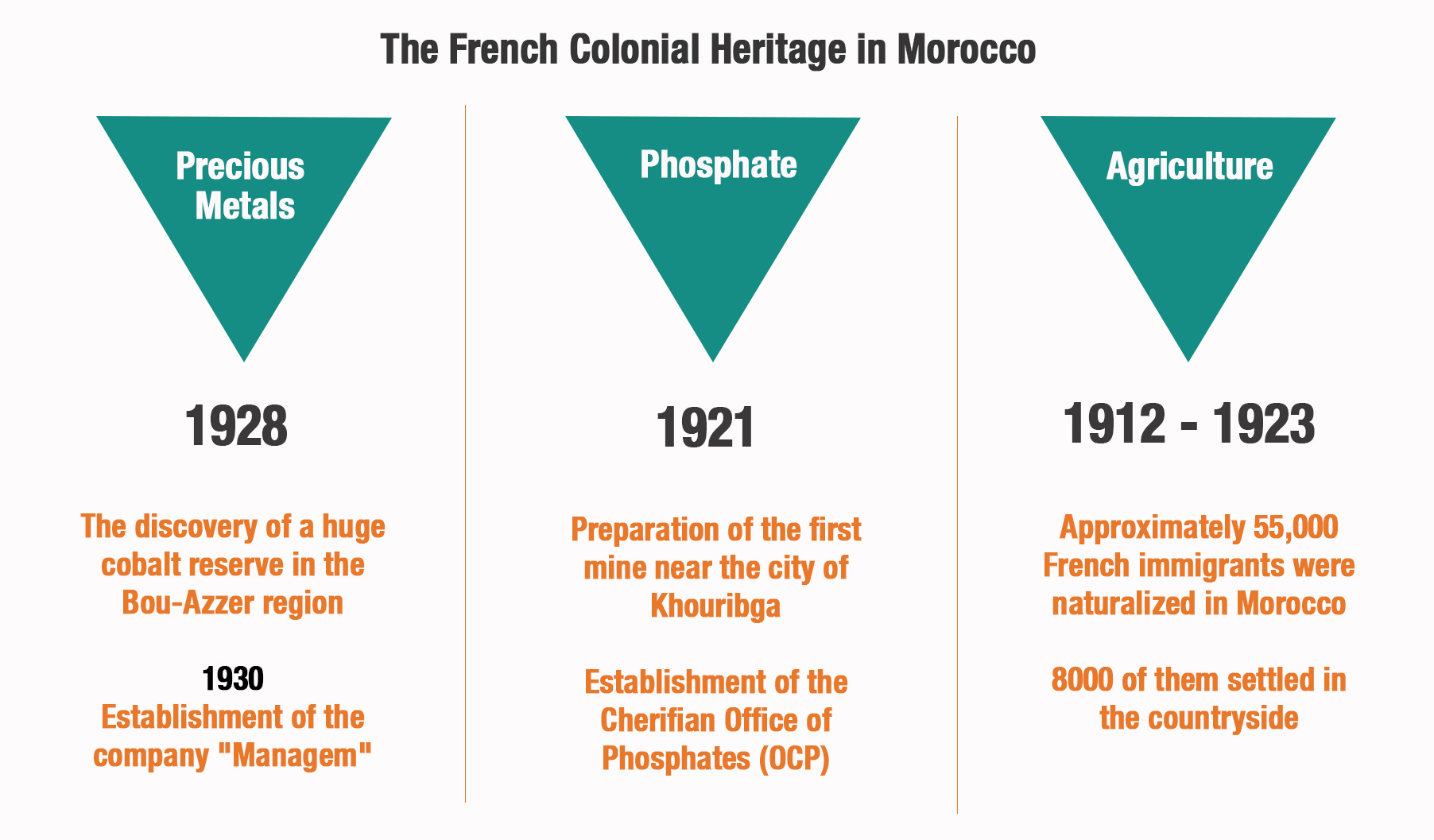

Unlike Algeria, which used to be a French governorate for more than 130 years, Morocco used to be considered a “protectorate” whose political and religious structures haven’t been significantly altered by the former colonial power. The sultanate system and main tribal structures remained untouched. On the other hand, France had no qualms about searching the entire country in pursuit of exploitable natural resources. Three domains were the potential objective of such a process, which required setting up the necessary infrastructure, to be able to practically and efficiently exploit such natural resources: roads, ports, railways, and so on. General Hubert Lyautey, the main engineer of French infiltration in Morocco, thought that a distinction should be made between a “useful” and “useless” Morocco, and act accordingly. As such, phosphate, agricultural production, and precious minerals formed the natural resources that had to be given exploitation priority.

It was only in 1921, that is, nine years following the establishment of the protectorate in Morocco, that the French authorities began extracting and treating phosphate – after setting up the first mine near Khouribga (in the centre of the country), where the biggest phosphate reserve in the world is located. In order to “manage” this sector, which would expand at a bewildering speed, the Group OCP (L’Office Chérifien des Phosphates) was created that same year.

General Hubert Lyautey, the main engineer of French infiltration in Morocco, thought that a distinction should be made between a “useful” and “useless” Morocco. As such, phosphate, agricultural production, and precious minerals formed the natural resources that had to be given exploitation priority.

The agricultural domain and fertile land exploitation had major economic stakes for the “French Protectorate” powers. As happened in Algeria, the best and most fertile terrains were given to French colonisers.

Precious metals are the other “natural resource” that Morocco has. Very early on, following their discovery of an important cobalt reserve in Bou-Azzer region (by Al-Atlas Al-Kabir) in 1928, the colonial authorities began to exploit those resources. Two years later, Managem company was founded, which also developed very rapidly. Currently controlled by the royal family, this company employs more than 5000 people and manages 12 mining sites in Morocco and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Finally, the agricultural domain and fertile land exploitation had major economic stakes for the “French Protectorate” powers, which aimed to enable French nationals to settle in Morocco. As happened in Algeria, the best and most fertile terrains were given to French colonisers. According to colonial statistics, between 1912 and 1923, nearly 55 thousand French immigrants settled in Morocco, 8000 of whom settled in the rural centre.

The exploitation of agricultural terrain by the French colonisers, with the material and political support of the French authorities in power, has contributed to the proliferation of modern farmhouses that became, by the end of the occupation, some of the biggest, most modern, and best equipped agricultural production units.

A major actor: the monarchy

As colonial powers departed in 1956, the three domains of agriculture, precious metals, and phosphate would become one of the most prominent structures of natural resource exploitation, as well as most coveted by the new political elite of the newly independent Morocco.

Soon enough, the Moroccan monarchy, along with its entourage, would impose themselves as the actors who determined the management and exploitation of such resources. They would do so either by granting themselves the power to appoint the public companies commissioned to manage these resources, or by directly controlling them, through privatization. The Managem company case is the most emblematic of such policies.

As of the 1990s, and through widespread privatizations of public companies led by Hassan II (1929-1999), the Moroccan monarchy was able to take hold of the Managem company. Later, the ONA Group followed (Omnium Nord-Africain), as did the National Investment Company, which today goes by Al Mada – the main financial group controlled by the royal family.

In a few years, Managem turned into a conglomerate, with its own international headquarters in the Swiss city of Zoug – the global capital for brokering primary resources, where fiscal policies that favour big corporations are applied. The group is now worth 500 million euros, according to figures published in 2018, and it runs ten mining complexes very rich in gold and silver, especially in Morocco and Sub-Saharan Africa. (See Managem company’s brochure and maps of mining sites in Morocco and abroad).

Managem thus turned from a public company into a private company controlled by Mohammed VI, a monarch by divine right with absolute political and administrative powers. Among these powers is the power to appoint senior officials, as stated in the constitution, which makes it easier for his company to obtain public contracts and attain precious metals exploitation and extraction permits in the mining sector. As such, Managem has an almost crushing monopoly over other companies, both Moroccan and foreign.

As of the 1990s, and through widespread privatizations of public companies led by Hassan II (1929-1999), the Moroccan monarchy was able to take hold of the Managem company. Later, the ONA Group followed (Omnium Nord-Africain), as did the National Investment Company, which today goes by Al-Mada – the main financial group controlled by the royal family.

While the royal group exploits these resources and enjoys all such facilitations, the sites of mining complexes themselves live as if they were in the stone age. In the Atlas Al-Kabir mountains, for instance, in the village of Imider, only two kilometres away from one of the biggest silver mines in the country (which produces 240 tonnes a year) exploited by Managem, no infrastructure exists: neither hospitals nor schools, while the only paved road that can be found dates back to the colonial era. Since 2011, Imider inhabitants have been leading one of the longest protests in Morocco’s history against the conditions they live and the destructive environmental consequences on their region, which are the result of exploiting and extracting minerals.

Phosphate: mismanagement and environmental disasters

Phosphate is yet another underground resource whose exploitation and management are the subject of recurrent debate. The OCP, which became a public company in 1975, has been overseeing the entire process of extracting and exploiting phosphate, considered to be “Morocco’s petrol”. According to official figures, Morocco (along with China) is the biggest phosphate producer in the world, as it is home to 75 percent of the global reserve. It has such a vast reserve that it would need seven centuries of exploitation for it to completely run out, as OCP officials affirm.

The "Gloomy" Economy of Morocco

15-07-2019

Morocco’s exports of phosphate and its derivates, the primary source of hard currency income, were estimated at nearly 5.1 billion euros in 2018. The way the OCP is run and the way its managers are appointed, though, is often criticised. Even if the head of government is the one chairing the board of directors, it is the general director appointed by the king who runs the group, who reports only to the head of state. There is no legal measure, for instance, that enables the Moroccan parliament to control the functioning of the OCP. In 2007, the famous American consultancy firm, Kroll, drew up a disconcerting report on the “catastrophic management” of the group, describing it as a “management with no real industrial or commercial strategy”.

Furthermore, the OCP has turned into some form of a “milk cow”, which the monarchy frequently uses to promote itself to foreign bodies, especially French ones. For example, every year, the OCP grants more than 700 thousand euros to the IFRI (L’Institut français des relations internationales) – a think-tank based in Paris, which produces “studies” that side with the kingdom and its leaders. And that’s not all, the OCP’s presence within the IFRI isn’t limited to organising international meetings or funding academic programs; Mostafa Terrab, the current CEO of the OCP is also a member of the IFRI board of directors.

Morocco’s exports of phosphate and its derivatives, the primary source of hard currency income, were estimated at nearly 5.1 billion euros in 2018. No legal measure exists, however, that enables the Moroccan parliament to control the functioning of the OCP.

Acting without the slightest independent monitoring, the OCP fails to adhere to international standards of respecting the environment and fighting pollution. As a result, the workers’ and local population’s right to health is systematically violated. A report published by Suissaid in June 2019 notes that the “two OCP-affiliated fertiliser factories (Safi and Jorf Lasfar), located by Morocco’s Atlantic coastline, emit large quantities of toxic gases that pollute the air and violate the workers’ and local population’s right to health. Many workers suffer from respiratory diseases and tumours as a result of their prolonged exposure to pollutants and fine particles. Many deaths have been reported among workers due to such conditions. The pollution that the OCP produces also affects local residents (respiratory disorders and dental fluorosis) as well as agriculture and livestock in the villages adjacent to the OCP’s work sites.

The sea, desert, and earth

With a coastline longer than 3500 km, considered one of the richest coasts in the world in terms of fish resources, deep-see fishing and the exploitation of sand quarries represent an important economic stake, with real revenues, from which the country’s powerful elite can benefit. To guarantee their “allegiance”, the Moroccan monarchy has granted the high-ranking military notables and the palace’s close circles “approvals”, like “licences”, of exploitation. These licences submit to no objective legal standards, and help their bearers enjoy the sea riches and make enormous amounts of money, thus becoming their “goose that lays golden eggs”.

In the wake of the Arab Spring of 2011-2012 and on the eve of entering government, the Islamic Justice and Development Party (PJD) promised to publish a list that contains the names of all beneficiaries of such approvals, in an attempt to maintain “transparency”. That did not happen, however; while a list was indeed published, it included no names. In fact, only the names of a number of companies (the people behind which would be impossible to identify) were published here and there, but without any real consequences.

Morocco has 3500 km of fish-rich coastlines. Deep-sea fishing and sand quarry exploitation constitute real revenues from which the country’s powerful elite can benefit. To guarantee their “allegiance”, the Moroccan monarchy has granted the high-ranking military notables and the palace’s close circles “approvals” (such as licences) of exploitation, which submit to no objective legal standards.

In an investigation published in 2012 by the independent website lakome.com, journalist Omar Radi noted some of the names of people who benefit from such approvals, most of whom are military and political figures, as well as Western Sahara notables (controlled by Morocco since 1975, although the Polisario Front has since been asking for independence). Despite everything, this report unveiled some famous names: General Abdelziz Bennani, whose name was noted in WikiLeaks documents on corruption within the army, and the two generals Hosni Benslimane, one of the most influential men in the kingdom, and Abdelhak Kadiri, former inspector general of the armed forces, both of whom had benefited from licensing deep-sea fishing, through the framework of a company called Kaben pêche. Still, observers agree, this was only the tip of the iceberg.

In addition to the high-ranking officials, Saharawi notables also benefit from important licences for sand quarrying and deep-sea fishing. Among those are former leaders of the Polisario (the Sahrawi independence movement) who have linked up with Morocco, such as Hassan Derhem, Mrs Gajmoula ben Ebbi, Hibatou Maelainine, and the Ould Errachid family.

The farmer king

Finally, agriculture constitutes yet another revenue from which the monarchy and the large landowners fully benefit. King Mohammed VI, it should be recalled, is the largest landowner, even if it is difficult to estimate the exact number of hectares he owns, as economist Najib Aksebi says. Moreover, even if he owned only 12,000 hectares, as some journalists have written, he would still be the largest landowner in the country. No other landowner, including Zniber, one of the biggest landowners, is known to have such a large number of hectares. Even the Kebbaj (Agadir, in the southwest) and Nouiji (the West region) groups lands do not reach 10,000 hectares (1).

Agriculture constitutes yet another revenue extremely exploited by the monarchy and large-scale landowners, while noting that King Mohammed VI is the country’s largest landowner.

The structure that manages the majority of the king’s agricultural activity has a name: The Domains Company. Its production is quite diversified, including cheeses, tropical fruits, vegetables, Atlas trout, honey, extra virgin olive oil, aromatic plants, and dairy products. A large part of these products is destined for export, especially to Europe, the most important market, followed by the Gulf countries, and especially Saudi Arabia.

Taxed revenues

In 1984, King Hassan II decreed total tax exemption for agricultural revenues, with a timeframe until 2010. In other words, farmers, including largescale landowners, were exempted from taxation. In 2008, in a speech to the nation, and two years before the decree expired, King Mohammed VI decided in turn to extend this measure – deemed unfair by most economists – all the way until 2014.

“The estimates regularly made here at the Agronomic Institute show more or less the same figure: the state loses 1.92% of GDP each year, which today corresponds to nearly 15 billion dirhams (1.4 billion euros) of annual losses in revenue for the Moroccan Treasury.” Mr Aksebi adds: “Is it normal today that an employee who earns 3000 dirhams (270 euros) pays his taxes, while a large-scale farmer who earns millions pays nothing to the state?”

At the time of writing this article, this “fiscal rent” has yet to be abolished…

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 11/07/2019

1-In an interview with the author.