This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Land is the pivot of the State’s sovereignty and authority in Egypt. It is also at the core of the social struggle between all parties, even inside the state's apparatus itself, as well as being the fundamental source of wealth in Egypt. But what is land? And why is it at the heart of the social struggle in Egypt? By land, here, we mean all that has to do with agriculture, whether in the Nile’s Valley, which is known historically as the agricultural lands of the Delta and Upper Egypt, or the reclaimed lands that came to being at the end of King Farouk's era and continued with Gamal Abdul Nasser's agricultural reform. These included the redistribution of lands, which was an important prelude for Nasser's project to redistribute wealth and form new social classes, in addition to the newly reclaimed lands in the desert such as Al-Tahrir District and the Noubariyah to the northwest of Cairo. Land also means the vast desert lands that constitute the urban sprawl of Egypt such as Heliopolis (Masr al-Gedida) and Nasr city in the 1970s. While in the 1990s and the new millennium, land also included the Sixth of October, Shiekh Zayyed and the gated communities and cities that have witnessed a colossal boom since the end of the last century and that are continuing to expand. These communities surround Cairo, and have come in the last decade to surround Alexandria too. The term also includes the vast areas on the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and even inside the cities and the villages or on their fringes. The agricultural lands, as well as the ones that are suitable for real estate investment, have been the main center of conflict and dominance. The seizure of such lands, aimed at demographic expansion through what is known as the slum belts or shantytowns, can be observed in Cairo, Alexandria, Canal cities, and many of the cities of the Delta and Upper Egypt.

The land in Egypt is not only the agricultural areas; it also includes any areas that are “investable”, whether in real estate, industries, or services. The problem of the land issue is embodied in two questions: Who has the right to the land? And, what should it be used for? There is also the question of integration and marginalization, whether concerning the right to access to the land and the right to the service, industrial, and real estate investment benefits that will be produced by allocating lands. Lastly, there is the question of who will seize the lands, in whose interest, and at what cost?

I - Milestones

From the fifties until today, three turning points can be observed in the conflict over land and its use.

Agrarian reform

The first milestone is the redistribution of agricultural lands, urban planning, and real estate investment, which was entirely managed by the state. This strategy was revoked by Sadat and the 1974 law which restored large holdings back to to the big landowners. It was during this period too that the private real estate market started to grow robustly. In addition, brokerage, land trading, and resolving disputes over it according to custom, became very important professions that made, and continue to make, fortunes for those who practice them.

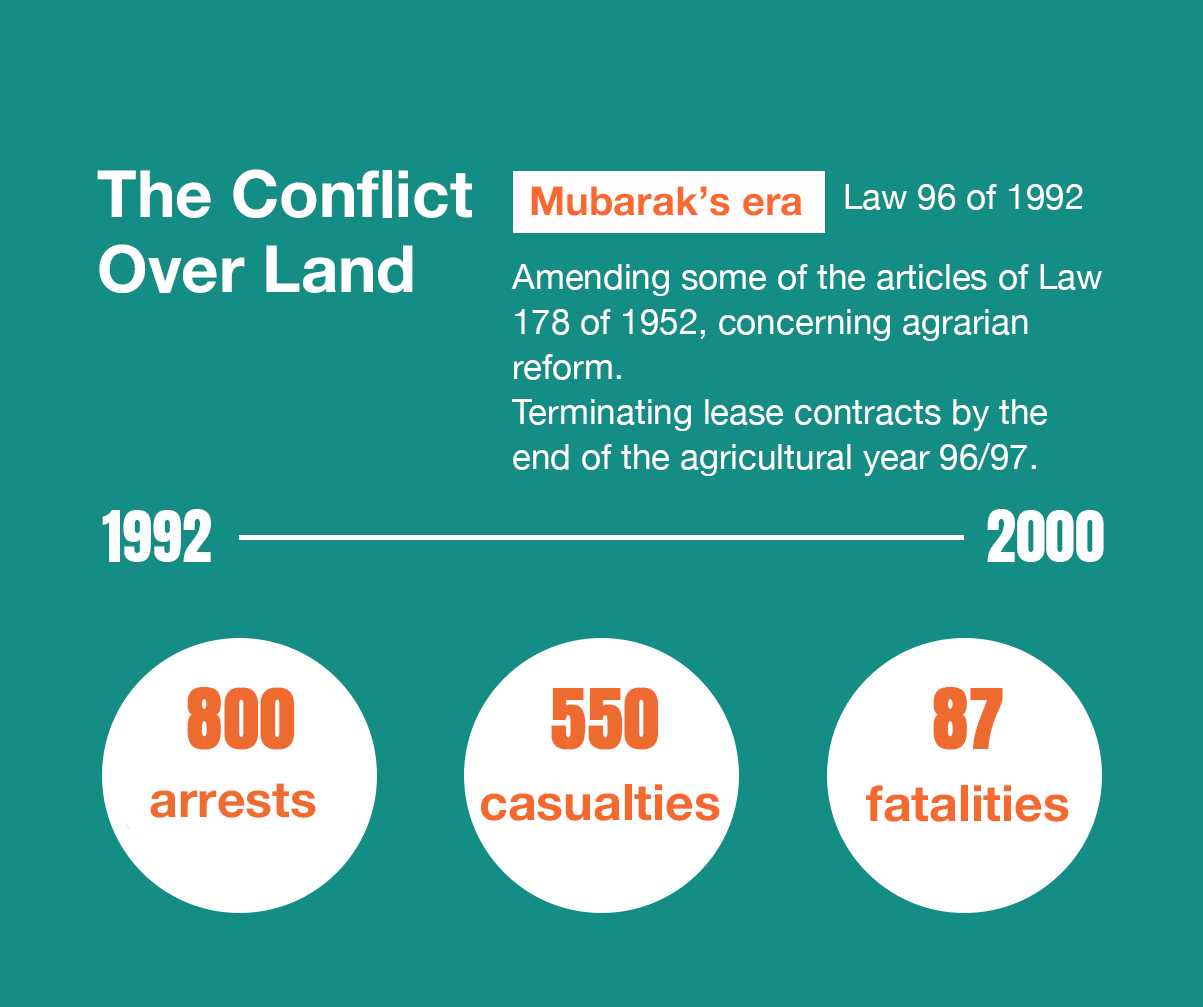

Mubarak’s era

The land became an object of speculation and “freezing” (bought according to certain conditions, but left unexploited). It also became a big field for practicing corruption by the security elites and the emerging classes as a result of the open door policy and the new capitalist elite that have been recomposed by various parties including the political regime itself, the United States of America, and the Gulf states, in the same period that witnessed the expansion of the slums and the touristic cities. With Mubarak, this mode turned brutal and witnessed violent clashes over both agricultural and real estate investment lands. In 1992 Mubarak changed the land lease law, that is, Law 96 of 1992, amending some of the articles of the Decree Law 178 of 1952 that dealt with agrarian land reform, stipulating the termination of the land lease contracts by the end of the agricultural year 96/97. Hundreds of small uprisings erupted in all Egyptian villages, from Upper Egypt to the Delta between the farmers on the one hand and the landowners and the security forces on the other. The uprisings were documented by the “Land Center” and included the blocking of roads and railways and the burning of many agricultural cooperatives. This era witnessed a blatant alliance between the landowners, the police, and the thugs (known as the “Baltagiyyah”). Ray Bush, a professor at Leeds University in Britain, asserts that there was an increasingly institutionalized use of torture and unlawful imprisonment of farmers and documented 87 mortalities, 545 casualties, and 800 arrests as the result of the conflict over land by February 2000. The same approach led to the events of Sarando in Damanhour (1) between 2005 and 2006, where disputes flared between the farmers on the one hand and the family of Salah Nawwar, the security forces, and the thugs on the other hand. There were many recorded cases of torture, one of which led to a woman’s death; women were detained and farmers arrested, as violence erupted.

Mubarak gradually abandoned supporting small farmers and agricultural reclamation projects for the youth. He chose instead to allocate vast areas of desert lands for commercial agricultural investment. This created another class of new major landowners. It also led to the expansion of agriculture by cultivating fruits such as oranges, through which Egypt has become a fierce competitor in exports, surpassing Spain at times, as well as planting herbs for exporting purposes and other horticultural crops. On the other hand, Egypt stopped caring about crops such as wheat, while in the Delta, rice cultivation and fish farms made huge returns until 2005, despite Egypt's conflict with Ethiopia over its share of the waters of the Nile and the “Renaissance Dam”.

Mubarak changed the land lease law, that is, Law 96 of 1992, amending some of the articles of Decree Law 178 of 1952 that dealt with agrarian land reform, stipulating the termination of the land lease contracts by the end of the agricultural year 96/97. As a result, many small uprisings erupted in all Egyptian villages from Upper Egypt to the Delta. The area of plundered lands during Mubarak's rule reached 16 million feddans or about 67 thousand square kilometers.

With the intensification of the housing crisis and the failure of the small lands acquisitions to produce profits for their owners, and with the impelling need to find lands for housing, the struggle over land for agriculture transformed into what is known as “Cordons” of buildings, which are chains of constructions that violate agricultural lands. This was the focal point of a long conflict that began in the 1970s and continues to this day between the state and the poor groups that sought to secure housing. The conflict materialized in the countryside as well as in the major cities such as Cairo and Alexandria. Thus, the slum belts expanded and many areas of what was known as agrarian reform lands were transformed into semi-slum residential regions after the failure of agriculture. The conflict grew deeper over these regions because the farmers on them held acquisitions of their lands, while the authorities provided them with services and public utilities such as water and electricity and collected the bills. Disputes over such areas as Toson and Al-Muntazah in Alexandria heightened at the beginning of the new millennium, and the administrative judiciary became a major arena for the conflict between the security, the governorate, and the real estate investors on the one hand, and the people on the other hand.

Despite the relative decline in the value of agricultural land, it remained a major focus of the social conflict between the big families and tribes over land ownership and the subject of aggressive competition among them to seize the lands of the state. The Land Center (2) has documented thousands of cases in which hundreds of victims fell annually as a result of the violence between the feuding parties.

The era of Mubarak was characterized by two contradictory phenomena: the first was the seizure of state lands as a result of the weakness of the authorities and corruption. The slums also turned into a social and security obsession for the government and a source of danger that needed to be contained. The second phenomenon was the avidity of the new capitalist elite, led by Gamal Mubarak, to seize the lands and evict the people, in a manner similar to what had happened in the 1990s when the farmers were evicted from agricultural lands, but this time it was happening in inhabited areas. The same period witnessed an expansion in land allocations and Gulf investments in the real estate and agricultural sectors. Emaar Emirati Company, Olayan Saudi Company, and the Kharafi Group were among the major real estate investors in Egypt, especially in the new cities or the touristic villages on the Red Sea. These investments helped the real estate market boom in Mubarak’s era, in the presence of bureaucratic difficulties, bribery, commissions, the state hegemony, and its monopoly over the lands. These are issues that business and finance men complain about, despite their closeness to the security elites and the mutual benefits.

In 2010, the Government Accountability & Audit Office published a very important report about the allocation and selling of the state’s lands that were intended for reclamation and cultivation. The report recorded thousands of violations and excesses that occurred in the last few years. It also talked about transforming the lands designated for agriculture (3.5 million feddans), which were sold at the cheapest prices, into touristic resorts and villas, especially those on the Cairo-Alexandria desert road and the North Coast.

The Arab Union for Combating Economic Crimes and Money Laundering revealed that the lands that have been taken over either by de facto seizure of land areas or through enacted laws are valued at 900 billion Egyptian pounds. The report also indicated that the lands and properties of the state have been subjected to gross and dangerous transgressions that violate the law and the constitution, and that this situation was sustained with the help of former officials, who profited off of allocating lands whose areas reached about 16 million feddans, or about 67 thousand square kilometers.

In 2010, the Government Accountability & Audit Office published a very important report about the allocation and selling of the state’s lands that were intended for reclamation and cultivation. The report recorded thousands of violations and excesses. It also talked about transforming the lands designated for agriculture (3.5 million feddans) into touristic resorts and villas, especially those on the Cairo-Alexandria desert road and the North Coast.

Furthermore, vast areas were designated for the new cities, such as Madinaty and Al-Rihab which were allotted to businessman Hisham Talaat Moustafa of the ruling National Party. This issue turned into a huge corruption scandal after the 2011 revolution. Mubarak expanded in transforming the region of Ain Sokhna into resorts and touristic villages, as well as the northern coast, southern Sinai, and some of the cities of the Red Sea. Big areas were allotted to Hussein Salem, the infamous businessman who was personally close to Mubarak, and who is today a fugitive in Spain, having been accused of various corruption charges that have to do with him being granted some lands for free. Investments, trade in lands, and "freezing" lands all turned into one of the most lucrative means of investment in Egypt, because real estate and lands retain their value against inflation, and as such, they are considered the safest fields of investment in Egypt.

After the revolution

After the revolution, most of the business moguls of the Mubarak era (Hussein Salem, Hisham Talaat Moustafa, Habib el-Adly, the housing minister himself, Ibrahim Soliman, and others) were accused of corruption charges, most of which concerned seizing state lands, either by laying their hands on them or by acquiring them through allocations from the government for much less than their market values. Many of these cases were settled by the payment of some compensations.

El-Sissi and Resource Management in Egypt

27-03-2022

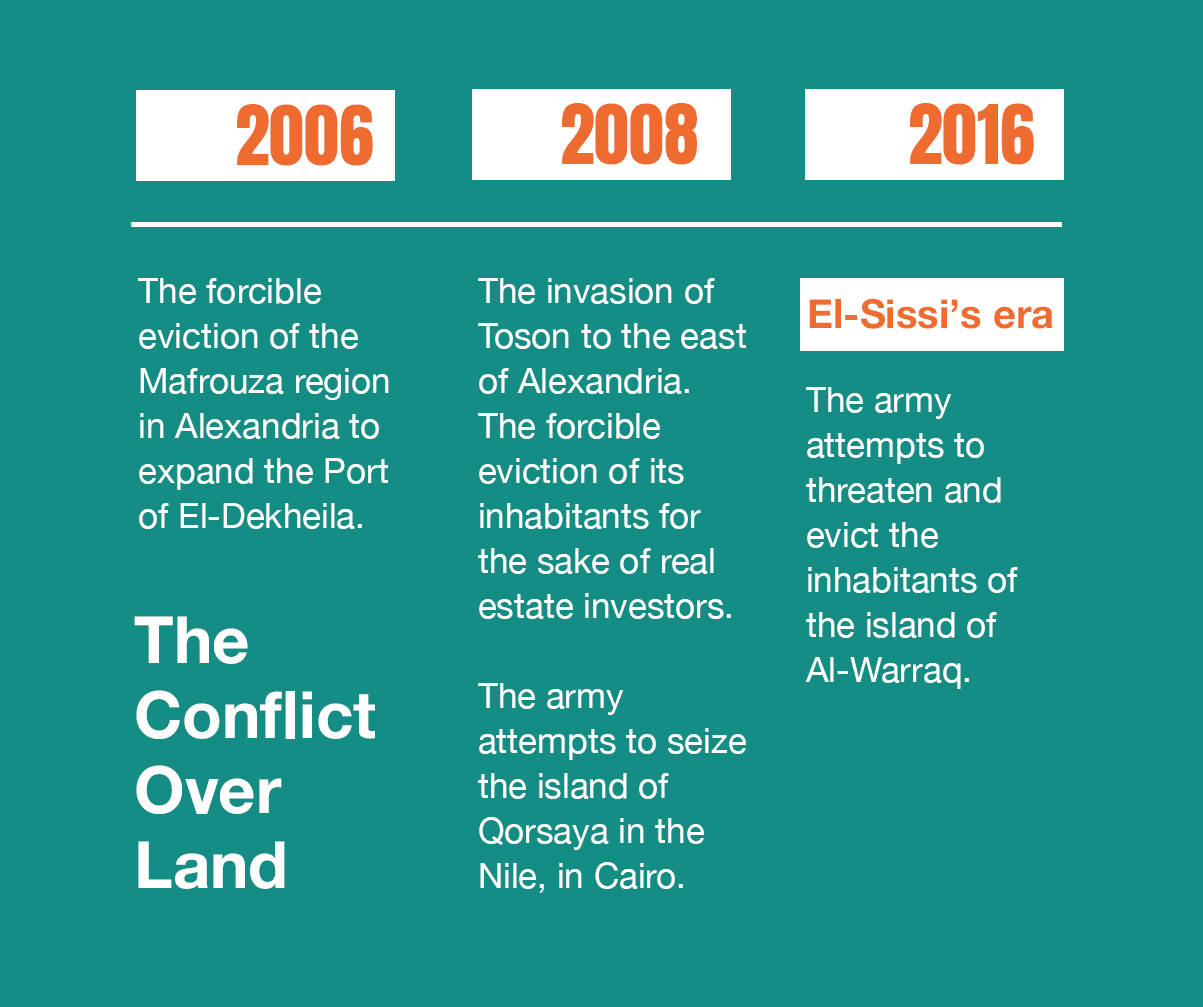

Thus, it is not surprising that since neoliberalism began to increasingly take root from 2005 until today, the attempts of the investors and those in power to expel the inhabitants out of their regions were markedly repeated. Examples of this abound. In 2005, the authorities evicted the inhabitants of the Mafrouza region in Alexandria to expand the Port of El-Dekheila. In 2008, the inhabitants of Toson to the east of Alexandria woke up to a large operation by the central security forces that aimed to evict them, following the decision of the Governorate of Alexandria and some businesspersons to invest in real estate there. In 2008, too, the army attempted to seize Qorsaya Island in the Nile in Cairo. Recently, the army also threatened the inhabitants of Al-Warraq Island in order to push them to evacuate the area. The government was also successful in evicting the inhabitants of the Maspero triangle to the benefit of the businessman Naguib Sawiris.

Thus, the political regime waged a large-scale war on the inhabitants of several regions to evict them by force, which was accompanied by mechanisms of brutality, mass repression, intimidation of citizens, jailing of citizens, and detaining of entire families as means of enforcing “compromise” and subjugation. In the end, a colonial and police state would be produced. That is why it is not surprising that the police are continuously militarized, regardless of the government’s concern about revolutions and political developments, since militarization is an integral part of the governance itself.

II – Maps, concerned parties, and the land conflict

Obtaining a detailed map of Egypt has become very difficult since 1952. Zakaria Mohieddin (the founding father of the contemporary security agencies in Egypt) was always very keen on keeping matters as such. Maps were, and still are, a very sensitive security issue for the Egyptian authorities as well as being a tool for planning and a source of wealth. This trend was enhanced with Sadat’s open door policy, since the land planning maps are what would empower various sectors (close to the authorities as a result of corruption or proximity between the state bourgeoisie and the emergent bourgeoisie which surfaced with the open door policy and was close to the security agencies, the army in particular) to seize lands, invest in them, "freeze" them, engage in brokerage, or receive commissions. Some of the officials close to the decision making circles have acted as “data brokers” about lands.

In the new millennium, things became even blunter, as the Egyptian Housing Minister became one of the partners in the Palm Hills Project which built gated cities and invested in real estate. Meanwhile, some of those who held governmental positions worked as consultants to real estate speculation companies.

Maps as impenetrable treasures

Getting a detailed map for investment in economic planning is something that is still very hard even today. The main problem is two-fold: either the map is secret and is exclusive to the security agencies and some planning departments, or it is under the jurisdiction of multiple departments that administrate land in Egypt, and hence requires various permits to be accessed for any kind of activity. These departments include the Ministry of Defense, the governorates, the ministries of overlapping powers, and the Endowment Authorities (Waqf). In addition, there are official bodies whose approval must be attained, such as the Defense Ministry, the Ministry of Military Production, the Civil Defense, and the High Council of Archeology. Reaching these departments and obtaining their approval is very costly and requires the ability either to access them through nepotism or corruption or both. The late civil engineer and political activist, Ramadan Jaballah, pointed out that the map is an integral appendage to the land as a major and decisive source of wealth, especially since the open door policy and with the advancement of transportation, road construction techniques, and the creation of new cities. Hence, the mere obtaining of maps, whether old, current, or future ones, has become a direct means for wealth. Some influential parties in the bureaucratic and security agencies have succeeded in obtaining the maps of the international highway in Alexandria after they were leaked, thus making a lot of money due to their access to knowledge about the lands and the means of investing in them. The same thing happened on the Cairo ring road. Jaballah continues to say: "I had an experience with the Egyptian Survey Authority, the civil authority that supposedly easily grants access to maps, in which I asked for a map of the Pyramids Gardens; they gave it to me after some bureaucratic stalling and red tape… Yet the map was a blank page, without any line drawn on it. I asked them if it were a printing mistake. They said: “No. This is it. This is a seventies edition. And if you want to get what you want, go to the office in El-Haram District.” Of course, the magnitude of the corruption of the district offices is well known and includes the disappearance of maps between the district office and the Survey Authority, for the benefit of the traders and the brokers, since the mere acquisition of detailed information on lands is a fortune to the brokers. This aspect confirms the security dimension when it comes to maps and their correlation with wealth, from the Al-Futtaim lands - EKEA and the Mall - whose maps confirm encroachments over a public road which was closed for these projects’ sake, to the maps of the small lands that went to the benefit of some of the corrupt men in power”.

Egypt ranks 119 out of 185 economies in The Registering Property Indicator of the World Bank. Sometimes, it takes between 10 to 15 years to register a plot of land in Egypt.

Despite all these complications, and the security agencies and the bureaucracy's “domination” over the land in Egypt, the efficiency of the government in registering lands is very modest. The seizures and laying of hands over the lands were also frequent. Dr Sahar Abboud indicated (3) in a report published by The Egyptian Center for Economic Studies that there is not “an integrated and updated information system about the lands in Egypt. Egypt ranks 119 out of 185 economies in The Registering Property indicator of the World Bank, and sometimes, it takes between 10 to 15 years to register land.

The army is the biggest investor

Due to the complicated procedures and the multiplicity of the relevant authorities, the ruling elite in Egypt resorts, through the president of the republic, to allocate the lands by employing direct presidential decrees or orders. After Mubarak, El-Sissi allocated lands to the armed forces or foreign parties by presidential decrees, such as his various decrees that allocated several lands to the King of Bahrain in Sharm el-Sheikh, treating him as if he were an Egyptian citizen. El-Sissi also granted a plot of land with the area of 164 feddans to the Prince of Kuwait, after enacting a law which stipulated that he be treated as an Egyptian citizen.

El-Sissi was very successful in playing the land game. And he managed to turn the army into the largest land investor in Egypt. During Sadat's reign, a presidential decree in 1977 gave the army the exclusive right to manage all non-agricultural lands, as well as all unexploited lands. This decree made the army the biggest administrator of the government lands in the country, giving unlimited dominance on the land to the Military Survey Administration, one of the administrations of the Egyptian Armed Forces Engineering Authority.

In 2014, a law that regulates the lands, which the army ceased to possess, was enacted. A new provision in this law allows the subsidiary institutions owned by the army to form companies, either individually or in partnership with the private or public sectors. This law facilitated the utilization of military lands in civilian, industrial, and investment projects. Merely obtaining old, new, or future maps became a means of obtaining wealth.

In 2014, a law that regulates the lands, which the army ceased to possess, was enacted. A new provision in this law allows the subsidiary institutions owned by the army to form companies, either individually or in partnership with the private or public sectors. This law facilitated the utilization of military lands in civilian, industrial, and investment projects in which the army would become a partner with its contribution of the value of the land only. This also means that land investments are added to the army’s privileges, whereas previously, during Sadat’s era, it could only seize certain lands, while during the reign of the ousted Mubarak, it was allocated 5% of the area of the built-up land. Mubarak granted the army the right of building 5% out of all the houses that were built in the country by the army and for the army, without generalizing the right of investing in these lands. However, a recent report by The Egyptian Institute for Studies (4) indicates that the army has now become entitled to both.

The army’s partnerships

In continuance of the direct allocation policy, Presidential Decree 57 of 2016 allocated to the Egyptian Armed Forces Land Projects Agency the lands of the administrative capital project and the Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed City to be built on about 16 thousand feddans. The decree also founded a shareholding company, which incorporated the agencies of the Egyptian Armed Forces Land Projects and the National Service Projects Organization to administer the lands. In 2018, the president issued Decree 108, approving the reallocation of state land plots in Al-Alamein (one of the cities of the Matrouh Governorate on the Mediterranean) to be used in building the new touristic Al-Alamein City. The most prominent provisions of the decree were conducting operations of reallocation and transport of properties from several parties, including the Ministry of Agriculture, Land Reclamation, and the Armed Forces to the New Urban Communities Authority. By these measures, El-Sissi succeeded in relocating the army in the Egyptian economy, outside the scope of its service and production projects, which have developed from the seventies until today. The army stands now as a key partner in any real estate or service investment project. The other active parties in the economy, whether the Egyptian businessmen or foreign investors, are obliged to work either in partnership with the army or under its approval. In any case, the land was the object of a conflict between the neoliberal elite, led by Gamal Mubarak, and the Armed Forces. The January Revolution has removed this barrier for the army.

Although the State was able to make such decisions, they were frequently appealed against both legally and constitutionally, as they contain a legal defect that turns against the state itself... And this is what some lawyers and activists are trying to do now in Alexandria, where the army has seized numerous lands, in addition to the beaches of Sidi Gaber and Mostafa Kamel neighborhoods, to execute certain recreational projects. But the army either subcontracts them to private companies, sells or leases the land, or allocates usufruct rights for a specific period. The legal defect, in this case, is that the beaches are public spaces whose seizure, concession, or private investment are not permissible.

III- The land, the law, and the colonial rule

Land is the key to understanding the nature of authority in Egypt, not because the country is a largely agrarian society, but rather because the Egyptian State focuses on the issue of land and deals with the population with the intent of subjugating groups of people living in specific regions or evicting other groups from their lands and displacing them.

In the past, and very reductively, the aim was maintaining the loyalty of a certain region and levying taxes from its population, as well as conscribing recruits, which made the military mode of government prevail over any other. It followed that the fundamental ruling technique was the military dominance and the besieging of territories. And the nature of the legal structure – whether the modern one or that which was being modernized, such as the case in the era of the khedives in Egypt- was based on collective punishment. The security system was distanced from the cities and based on the system of collective responsibilities. That is why the law (Khedive Firman) continued to permit the practice of taking prisoners from amongst the people to negotiate or pressurize the offenders to turn themselves in, that is, until the 1923 constitution that stipulated individual punishment.

The ruling mode based on collective intimidation returned in the nineties to evict the population from the agricultural lands, but this time with a different administration and projects, and a legal structure that frequently contradicted the techniques of police rule. In the new millennium, this mode came back to be practiced with the lands that are suitable to invest in real estate and touristic projects. For example, there is the dilemma of the land on the north coast, which serves as an example to demonstrate the prevalent form of real estate and touristic investment in land. The population there was marginalized and then integrated with the “development process” with its clientele networks, authoritarian relations, and legal complications.

According to the administrative division, the north coast of Alexandria Governorate was a border region. The inspection gate used to begin at the kilometer 18 or the El- Dekheila region. Thus, it is a border desert region of a stretched coast. The value of the coastal lands in this area was trivial, and it had no real economic or financial weight, being that it was not part of the urbanization and development projects. The army used to control most of the coastal lands through the domination of the border guards of the coast. And since the land was worthless, there was virtually no feud over the land between the population and the army except when the army seized some land to build posts for the border guards. However, things completely changed when the government decided to turn this coast into a touristic internal region and build what is known as the touristic villages, marking the beginning of the struggle over land between the population, the state, and the investors.

Most of these lands are historically owned by the indigenous tribes and families. Each family knew the borders of its lands and its geographic influence. Of course, some disputes used to occur over the lands between the families, but they were resolved by the customary councils that resorted to the experienced elderly who possessed a sharp intuition and a historical, deep-rooted knowledge of the land ownership and its distribution among the families. This was the case in the regions inhabited by the tribes known as Abnaa Ali. In the Delta, too, there were similar councils composed of dignitaries, or statesmen, mayors, and village chiefs. They used to mark the borders of the lands with pine trees saying that at a certain tree one property ends and another begins.

The north coast of the Alexandria Governorate was a border desert region of no real economic or financial value, as it was not a part of the urbanization and development projects. And since the land was worthless, there was virtually no feud over the land between the population and the army. However, things completely changed when the government decided to turn this coast into a touristic internal region and build the so-called touristic villages, marking the beginning of the struggle over land between the population, the state, and the investors.

The land was always, and it still is, the source of influence, wealth, power, and social status. That is why a dispute over land might lead to violent conflicts between some families, which might extend for decades. Several agricultural lands in Edku (in the Beheira Governorate to the west of the Delta, with Damanhur as its capital, bounded in the north by the Mediterranean) are, for example, not registered. The farmers there relied on one of the laws of the agrarian reform that stipulates that the one who reclaims a land owns it. They actually reclaimed what is known as the sandy Kizans (dunes) to grow apple trees and vines, as well as other crops. However, they were not able to legalize their statuses, and they are now facing a big problem, with the governorate accusing them of being thugs who are seizing state lands. Moreover, both parties claim that the law is on their side.

Selling Egypt's Assets: Who Has Ownership?

14-06-2022

With the advent of this new form of urban expansion and touristic/services investment, a new problem has emerged: the historical ownership of the indigenous inhabitants. While most of the lands have not been registered or legalized, the state claims their ownership. Therefore, the investors had to face the question of who owned the land, and they had to resort to the customary solution: the investor pays the price to the state or obtains the legal papers from the Ministry of Defense or the Land Reform Authorities. He then pays a customary estimated price to the owners of the land. The families and the tribes felt resentment as their lands were being taken from them. To compensate for their losses, they imposed what is known as "ghufra" or "ujara" (which is a monthly payment in return for security services and a monopoly of supplying building materials and sometimes workers). However, things have not gone smoothly, and the conflict over many lands continues to reignite violence. Not long after the government's decision to invest in tourism in the region in the late 1970s, a small uprising erupted in Abu Talat, an area located 21 kilometers to the southwest of Alexandria. A dispute between a police officer and one of the families in the region quickly turned into violence between the police and the local population. The internal security forces besieged the region, and the incident ended with negotiations, after the Bedouin population was intimidated and rendered weaker, as some of the commanders of the Internal Forces attest. The price of the coastal lands in that region increased, reaching 11 million Egyptian pounds for a single housing unit, and the price of one square meter in certain touristic villages ranged between 30 and 40 thousand pounds. The state continued expanding in the northwest of the region, as new investors grew more powerful and influential, and the status quo was maintained as such until the January 2011 Revolution. After the revolution, the tribes and families remained committed to the customary covenant and the practice of ghufra, and they were able to keep the peace in the entire region.

Something in the behavior of the authorities resembles the colonial nature, which is based on the forced displacement and non-integration of the indigenous population. The State, therefore, pushes all parties to compromise and drives them to use bribery and violence.

Nevertheless, this region witnesses constant feuds over land. There is, for example, an existing conflict between some farmers from the Delta who reclaimed extensive areas of land, some local inhabitants who do not abide by the law or recognize customs, and some of the judiciary and police. We do not aim, here, to say that the right is with one party or the other. However, the ambiguity of the law and the rise in the prices of the lands has made them the object of constant struggle, whether for use in agriculture or to be invested in tourism and services.

The conflict also transcends these parties. The army itself which has considered that it was permitted (by law) to seize any non-agricultural land, for military, security, and logistic purposes, found itself in 2015 on the verge of a violent clash over the land of the nuclear power plant in El-Dabaa. The army evicted the inhabitants of the area who started a small rebellion, occupying the land and refusing to be forcefully evicted. The army made a show of force to deter them, spreading its troops all over the area, as eyewitnesses have said, while military planes hovered overhead. After intimidating and terrorizing the locals, the feud ended, as always, by negotiations, after which the army paid some compensations to the land owners. In fact, the army is planning a monumental and ambitious project in this region and is currently completing the construction of the summer capital in the new city of El-Alamein, which is expected to attract foreign investors and private security companies and increase the militarization of the area. This will certainly change all the security, social and customary equations in that region. Indeed, something in the behavior of the authorities resembles the colonial nature, which is based in the forced displacement and non-integration of the indigenous population. The State, therefore, pushes all parties to compromise and drives them to use bribery and violence.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Ghassan Rimlawi

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 15/04/2019

1- The Land Center (2005): Excuse me, Mr General Prosecutor. Other reports document the incident in Sarando village. The Land Center for Human Rights, Civil Society Series, Issue Number 17.

2- Ishmawi, Sayyed (2001). The Farmers and the Authority in Light of the Egyptian Farmers’ Movements (1919-1999). Merit Publishing House, Cairo.

3- Abboud, Sahar (2018). The State Land Administration System in Egypt: Current Status and Development Proposals. The Egyptian Center for Economic Studies.

4- Ibrahim, Mustafa (2018). The State Lands in Egypt: Who is the Owner? Egyptian Institute for Studies.