This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Since the late 1800s, football has captivated Egyptians from the lower classes, offering them an exceptional opportunity to express their rivalry towards the British and show their national identity. Contrary to the sports favored by the rich, football carried all those implicit meanings, and, as a result, the public perception of football shifted from being a sport that reflected the culture of “the other”, the British, to a popular lever for the national movement, and from a game that perpetuated the Egyptians' sense of oppression by the colonizer into a means of resistance by the colonizer’s own weapon. Since then, football has not ceased to be a “political tool”, in the noble sense of the phrase.

While ball games were played in Ancient China and Ancient Egypt before spreading to the Greeks and Romans, modern football originated as a colonial tool used to educate and discipline Egyptian workers and soldiers in occupation camps. However, the independence movements quickly adopted the game, turning the neighborhoods and alleys into football pitches and vital social spaces. During the occupation between 1882 and 1895, most Egyptians resisted football, considering it to be one of the occupier's means of influencing them. In February and March 1892, editorials appeared in Al-Ahram newspaper warning people about the "English game." The decision made by the Minister of Education to introduce physical education and football as compulsory classes in schools was faced by strong condemnation by most and was described as a plan to prevent the creation of a national elite by imposing colonial educational values (1).

This public perception of football persisted until 1895, when some Egyptians started to view the game as a tool of resistance. In the British army camp in Cairo’s Abbasiya, Muhammad Effendi stood observing the occupation soldiers playing football, and in that moment, an innovative idea of a resistance without bloodshed or guns crossed his mind. Muhammad Effendi saw an opportunity to domesticize the colonial game and contribute to its dissemination as a symbolic challenge and a way for organizing and educating the masses. He formed the Egyptian team, then challenged and defeated the Orans team which represented the British army. The match marked the starting point for the game's history in Egypt and became a symbol of resistance.

The bases for supporting or opposing football in Egypt remained blurry until the establishment of Al-Ahly Club in 1907. From that point onward, football, according to specific contexts, began to be regarded as the "opium of the masses." But how did this transformation occur?

The National Team

In 1943, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini, approached Fouad Serageldin, the president of the Al-Ahly Club and Minister of the Interior, to host Al-Ahly on a tour in Palestine to support the Palestinian resistance against the British and the Zionists. Al-Ahly president and team captain Mukhtar al-Tetsh agreed to the proposal; however, the king, the occupation, and Haydar Pasha, the president of Al-Mokhtalat (currently Zamalek SC) and the Egyptian Football Association (EFA), refused the idea.

Al-Ahly circumvented the travel ban and went to Palestine in 1943 on a 23-day tour, under the name of the Cairo Stars team. Upon their return to Cairo, Al-Ahly found that the EFA had issued a decision to suspend the team’s sports activities for several months. In response, fans organized a massive demonstration at Abdeen Palace, where they chanted slogans against the king and the occupation. This frightened the king who ordered the immediate annulment of the decision. As a plot against Al-Ahly, EFA chairman Haydar Pasha decided to hold the postponed Egyptian Cup Final 1943/44 between Al-Ahly and its historic rival, Zamalek, when the suspension was still in effect, forcing Al-Ahly to send its junior players to the pitch since the players who had visited Palestine were still suspended. Al-Ahly was defeated 6-0, but it was a defeat with the taste of victory. While Al-Ahly continued to pride itself about the 6-0 defeat as a testament of its "patriotism," Zamalek boasted of it as evidence of its footballing supremacy.

Al-Ahly Legends is a famous anthem in Egypt that praises the courage of Al-Ahly for supporting Palestine and opposing the Zionist movement. It honors those who have managed the club since its inception. The lyrics say:

Omar Lotfi was a lawyer and revolutionary

He defied the occupation and stood against it

He fought for independence and built Al-Ahly Club

It was his dream to establish the first national club

In 1943, Mukhtar al-Tetsh disobeyed the king

and led Al-Ahly on a journey to Palestine

Our 6-0 defeat by Zamalek is a badge of honor we wear until Judgment Day

The stance of Mukhtar and Haydar is a crown of pride that lights our way”

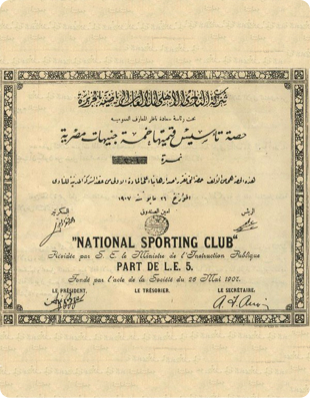

Let's start at the very beginning. Before the establishment of Al-Ahly, foreign communities residing in Egypt founded several social and sportive clubs. The British authorities founded the first sports club for workers, Al-Seka al-Hadid (The Railway Club) in 1903, which allowed Egyptian workers in workshops and camps to apply for membership. It was preceded by the Khedive's Club for Officers and the British Community (Al-Jazeera today) in 1882. This club prevented Egyptians from applying for its membership until 1956, after which royalty and wealthy people exclusively were granted membership. To this day, Al-Jazeera Club continues to apply this policy. It has the highest membership fee, which amounted to 1.5 million EGP [about $48,500] per member in 2023. This was one of the main reasons that prompted the national movement to consider establishing a club for students.

Hence, the High School Students Club was founded in 1905 as a political club. Afterward, its president Omar Lotfi established the first Egyptian sports club for all Egyptians. After further discussion with friends, Al-Ahly was established in April 1907 with a power base of high school students. Saad Pasha Zaghloul was the first head of the General Assembly. Mitchell Innes was elected the first president for only one year to take advantage of his influence and expertise in the founding period. In fact, the establishment of Al-Ahly was in response to the emergence of British and mixed clubs in Egypt.

Throughout history, Al-Ahly has earned its reputation as a national player. Historically, the club refused to participate in the championships organized by the Mixed Federation for Sports Clubs, which was largely run by the British, putting forward the idea of nationalizing sports federations. Al-Ahly fans occupied a significant space in the public sphere, and they used to stage popular demonstrations after each victory scored by their club over a British team. Al-Ahly members also volunteered to defend Egypt in the wars waged against it in the 20th century. They were at the forefront of the Fida’yeen resistance groups in the 1948 Palestine War. Al-Ahly also turned its stadiums into training centers for members of the popular resistance in the 1956 Suez Canal War and the 1967 War.

In 1943, Al-Ahly was invited to visit Palestine to support the Palestinian resistance against the British and the Zionists. However, the king, the occupation, and Haydar Pasha refused the idea, but Al-Ahly circumvented the travel ban and went on a 23-day tour to Palestine, under the name of the Cairo Stars team.

Several other factors have contributed to making Al-Ahly the most popular football club in Egypt. According to a local study conducted in 2014, 72% of football fans in Egypt support Al-Ahly, while its closest competitor, Zamalek, had only 21% of the fanbase. On social media, Al-Ahly sits comfortably on top of the game among Egyptian, Arab, and African football clubs, with millions of followers across various social media platforms. All this made Al-Ahly a football phenomenon; an "almost incomprehensible miracle," as described by journalist Fikri Abaza.

Historic arch-rivals

Many wonder about the reasons behind the historical rivalry between Al-Ahly and Zamalek. Exploring the historical and social contexts in which the Zamalek was established can provide some answers. Al-Ahly's growing popularity in Cairo prompted the Belgian George Merzbach to found Qasr al-Nil Club in 1911, which was later known as the Cairo International Sports Club (colloquially El-Mokhtalat Club) because it allowed both Europeans and Egyptians to apply for its membership. Unlike Al-Ahly, it was a club for the affluent class. The club was renamed after King Farouk of Egypt, and it became known as Farouk El-Awal Club and remained associated with the monarchy until the success of the Free Officers Movement in seizing power in 1952. From then on, the club adopted the name Zamalek, and its nickname was the Royal Club. Hence, the two clubs, Al-Ahly and Zamalek were established based on political and class orientations and tendencies. For instance, in 1916, Zamalek won Sultan Hussein Cup, which included Egyptian and British clubs, while Al-Ahly refused to play with colonial clubs.

There was no direct animosity between the two clubs until 1914 when player Hussein Hegazy decided to leave his English club and return to Egypt. This sparked a heated battle between the two clubs over Hegazy’s transfer, as he went back and forth between the two clubs until his retirement while he was playing for Zamalek. The conflict continued between the “club of the people,” Al-Ahly, and the “club of the rich,” Zamalek, for nearly 90 years. Tensions escalated in 2000 when the Confederation of African Football (CAF) awarded Al-Ahly the title of African Club of the Century. Hostility increased between the two clubs' fans, especially after Zamalek's fans demanded CAF award Zamalek the title instead of Al-Ahly. It is worth noting that Zamalek ranked sixth, according to the CAF classification at the time.

Zamalek and its fans have led campaigns accusing Al-Ahly of corruption and accusing football officials in Egypt for showing favoritism towards Al-Ahly, regarding it as the state’s pet club. It is true that Al-Ahly wields significant social and political influence in the country, given that it has the largest fan base. Evidence of this influence appeared when Saleh Selim, the club's president, refused to receive the late President Mubarak after the presidential plane landed on the club's pitch against his will, and again when Selim refused presidential directives to hold a match between the two poles of Egyptian football following the tragic Upper Egypt train accident in 2002.

However, the animosity towards Al-Ahly goes beyond the Zamalek fanbase. There are some popular football clubs in the provinces whose fans bear hostility towards Al-Ahly, such as the Ismaili Club (founded in 1924) and Al-Masry Club based in Port Said (established as the first club for Egyptians in the cities of the Canal in 1920). These clubs’ fans supported whichever club played against Al-Ahly, which meant that they aligned themselves with Al-Ahly’s arch-rival, Zamalek. Nevertheless, the number of Al-Ahly fans is notably increasing in the governorates of Lower and Upper Egypt.

Football as a class game

Football has always been a game for the working class. It was passed on with ease from the poor occupation soldiers to the residents of the narrow streets and alleys of Egypt, where the underprivileged found solace and joy in the game after decades of deprivation. This was characteristic of the game elsewhere as well. The British Isles had dismissed football for centuries, and it was described as "a social vice practiced only by the lowest classes," as author Eduardo Galeano documents in his book "Football in Sun and Shadow." The affluent class, both British and Egyptian, looked down on football as belonging to poor people. However, the decision of the Minister of Education to include it in physical education classes in 1892 was a pivotal moment that reshaped the social map of football in Egypt. When the British High Commissioner abolished free education, only children of wealthy families who could afford the fees remained in schools. Thus, the opportunity arose for children of the wealthy class to play football as well. However, the two classes evidently held different perspectives on football: while the wealthy saw it as a leisure activity, the poor embraced it as a vital form of self-expression.

The Qasr al-Nil Club was established in 1911. It was later known as the Cairo International Sports Club, or El-Mokhtalat (mixed) club, because it allowed Europeans and Egyptians to apply for its membership. Unlike Al-Ahly, it was a club for the affluent class, and it remained associated with the monarchy until the success of the Free Officers Movement in seizing power in 1952. From then on, its name became Zamalek, and its nickname was the Royal Club.

Football has provided solace and escapism, particularly for young people experiencing poverty, exclusion, and social marginalization. However, since the introduction of the professional football system in Egypt, the game has turned into a means to move up the social ladder. In clubs like Al-Ahly and Zamalek, players receive a minimum salary of 7 million EGP (about $226,515) per season, while in less renowned clubs in the Egyptian Premier League, salaries stand at around 500,000 EGP or slightly higher.

Nevertheless, playing football or supporting football teams remained a form of social rebellion against the disparity in income and wealth distribution, as well as the erosion of the middle class resulting from the state's abandonment of its social responsibilities towards its citizens. That is in addition to the repressive climate and the monopolization of the public sphere that characterized the rule of former President Hosni Mubarak, together with the regime's lack of ambition, resources, and institutions which might be able to engage and support the frustrated youth.

Perhaps that rebellion was evident in the movements of the football-passionate fans, widely known as the Ultras, who have emerged in Egypt since 2007. Ultras harnessed the power of social media, mobilized, and networked with group members to claim their space in the public sphere and break the arbitrary ban imposed by the regime or club administrations. The Ultras emerged as an unconventional alternative to demonstrations, openly expressing their political leanings in the stands by adopting multiple discourses. At first, their slogans took a sport-themed tone against football capitalism, but they later turned into expressions of revolutionary protest (Al-Ahly Ultras and Zamalek Ultras took part in the events of the 2011 revolution). Eventually, the slogans took on political and religious dimensions, with some of the Zamalek Ultras joining political-Islamic groups and founding the movement Hazimun wa Ahrar (“The Determined and the Free”).

The 2006 Africa Cup of Nations marked a turning point for football within Egyptian society, attracting new audiences from the upper middle class and women. It is possible to say that this tournament contributed to opening up the public space for Egyptians; allowing millions of people to attend at the stands and streets after each match at a time when gatherings were prohibited. It also led to the emergence of the Ultras in the following year.

Following the 2011 revolution, football became a powerful tool for political and mass mobilization through the activities of the Ultras in various areas. In this regard, researcher Ziyad Aql said that football created a sense of national belonging among Egyptians, which the usual political entities failed to achieve. He added that using football as one of the mechanisms for shaping national affiliations occurred due to the absence of sufficient collective entities capable of expressing a distinct identity.

Game to industry

Political systems quickly recognized the ability of football to deflect attention from political and social grievances and growing resentment over economic crises and police violence. For example, the Mubarak regime arranged for the president to attend the final match of the national team in the 2006 Africa Cup of Nations, aiming to distract people from the tragic sinking of the Al-Salam 98 ferry in the Red Sea that same year. The regime also used the home and away matches between Egypt and Algeria in the 2010 qualifiers to legitimize its political actions. Moreover, on the first anniversary of the Battle of the Camel, which witnessed the Ultras defending Tahrir Square and the demonstrators, the regime took revenge on the Ultras in the infamous Port Said massacre in February 2012 (2). In February 2015, another massacre targeted the Zamalek Ultras, effectively ending the Egyptian ultras phenomenon. Even the football fans have disappeared from the stands and public squares until present.

El-Sissi and Resource Management in Egypt

27-03-2022

On the economic level, football has turned from a game into an industry after introducing the professional system in the 1990s. The transformation marked the birth of a new form of football as a game for the masses that carries different values and relies on youth as a consumer audience and as active supporters who are familiar with the tools of the new football era.

The 2006 Africa Cup of Nations marked a turning point for football within Egyptian society, attracting new audiences from the upper middle class and women. The tournament contributed to opening up the public space for Egyptians, allowing millions of people to attend at the stands and streets after each match at a time when gatherings were prohibited, and eventually leading to the emergence of the Ultras.

Football turned from a game into an industry after introducing the professional system in the 1990s. However, the rise of the sports economy paved the way for the emergence of the Ultras, who categorically rejected the dominance of capital over their popular game.

The rise of the sports economy paved the way for the emergence of the Ultras, who categorically rejected the dominance of capital over their popular game. The Ultras, an extension of Al-Ahly fans who have emerged abroad since 1996, launched a website and the Al-Ahly Fans Club (AFC) association in 2005 (3). An association of Zamalek fans emerged simultaneously.

However, one young Al-Ahly supporter, Amr Fahmy, was uneasy about the way the fanbase was organized. Fahmy (4) drew inspiration from the Italian experience, and expanded the Ultras experience in Egypt, considering that football fan associations had fallen into the trap of subordination to club leaders. The interests associated with profitable and non-profitable activities outside the stadiums have become prominent. Consequently, the birth of the ultras was a form of rebellion against the subordination and paternalism practiced by the boards of directors of the two clubs over their own fans, who raised slogans like “football is for the people” and “we are against the police, capital, and the media.”

Since 2006, investments in sports media have exploded, with sponsors raising the value of the Egyptian Premier League. In 2020, the Egyptian Premier League ranked second in the list of the richest football leagues in Africa, with a net valuation of approximately 138 million euros, while the value of football-related economies in Egypt was 1.25 billion EGP (about 38 million euros) in 2012. This new situation has forced fans to buy tickets at higher prices to attend matches.

The current regime wanted to invest in football to create a new revenue stream, opening the door to foreign investment. Turki Al Al-Sheikh, chairman of the Saudi General Sports Authority, bought Al-Assiouty Club and changed its name to Pyramids FC, then launched a channel of the same name in 2018. Pyramids finished third in the 2018–19 Egyptian Premier League. However, the Saudi owner had numerous conflicts with Al-Ahly, resulting in his withdrawal of all investments and departure from Egypt.

In 2019, the authorities launched the "My Ticket" system to regulate the audience, maintain accurate spectator records, and control the clothing and sports equipment market by granting monopolies to specific companies. In the past, TV subscription cards were introduced to allow viewers to watch matches from home, with the Saudi ART channels holding exclusive rights for years. Later, the exclusive rights were transferred to the Qatari beIN Sports channels, which meant less access for the poorer fans to watching the tournaments.

Despite increased investments in the football industry and market, the desired economic benefits for the Egyptian economy remained limited. The revenues generated by the industry do not constitute more than 2% of the state's financial resources. Perhaps this is due to the Sports Law, which previously granted clubs the right to obtain significant facilities and tax exemptions almost free of charge.

The current regime wanted to invest in football to create a new revenue stream, opening the door to foreign investment in Egyptian football through Turki Al Al-Sheikh, chairman of the Saudi General Sports Authority. Al-Sheikh bought Al-Assiouty Club (a privately owned club) and changed its name to Pyramids FC, before he launched a channel with the same name in 2018. Pyramids FC finished third in the 2018–19 Egyptian Premier League. However, the Saudi owner had numerous conflicts with Al-Ahly and its fans, resulting in his withdrawal of all investments and his departure from Egypt. This ultimately failed experiment disrupted the Egyptian league because it raised the financial ceiling for player contracts to absurd amounts.

In 2019, the authorities launched the "My Ticket" system to regulate the audience, maintain accurate spectator records, and control the sports market through monopolies. In the past, TV subscriptions were introduced to allow viewers to watch matches from home, with the Saudi ART channels holding exclusive rights for years. Later, the exclusive rights were transferred to the Qatari beIN Sports channels, which meant less access for the poorer fans.

In early April 2023, Salem Al-Shamsi, the current Emirati owner of Pyramids SC, issued a statement announcing his decision to withdraw his sports investments from Egypt, in protest of what he called "the unfairness of football referees." The decision was another sign of the failure of the Gulf investment in sports experiment in Egypt, bringing the sports investment issue back to the fore.

The current authority, aiming to attract investments and raise funds to facilitate its major projects, now views football as an industry. President El-Sissi expressed this perspective at the 2019 youth conference, as the regime continues to set the ground to capitalize on football, overlooking the fact that the game is the only enduring source of joy for the poor.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 20/05/2023

1- The decision to amend the study plan in Egyptian schools was issued to approve teaching geography, history, and natural sciences in English, canceling the time allotted for studying the Turkish language and adding two hours per week for physical education. It was indeed a British plan to reduce the number of accredited education hours; it prompted the Shura Council of Laws to object two years later to the neglectful ministry of education.

2- On the Port Said massacre: see an article in Assafir Arabi by Islam Daif, https://bit.ly/3oiBGi1, and "The Port Said Massacre: Forgotten by all, revived by Abu Trika", https://bit.ly/3o4MP64

3- A.F.C or Al-Ahly Fans Club is an association formed in 2005 and officially supported by the club’s management at that time.

4- Amr Fahmy was an Egyptian football manager and the General Secretary of CAF from 2017 to 2019. He resigned after discovering widespread corruption in the CAF. He was known as one of the founders of the Al-Ahly Fan Club or the Al-Ahly Ultras. In 2020, he passed away in his prime due to illness.