This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The Tunisian state has propagated the narrative that Tunisia is a poor country which hasn’t been blessed with many resources, unlike its two neighbours, Libya and Algeria, both rich in oil and gas. All that Tunisians possess, as Bourguiba would repeat, is their “raw matter”, by which he means the Tunisian brains which are the country’s means of growth. “Pure Tunisian intelligence” would subsequently become a catchphrase. The natural resources that Tunisia could potentially possess were not addressed, however. Even geography classes at schools don’t provide much about these prospects. Tunisia is merely described as a country that overlooks the Mediterranean, with tourism as its main source of income - to the point where everybody would repeat that we were a poor country living off of tourism, a little bit of farming, and much external debt.

However, the 2011 revolution disrupted the “code of silence”, and so the discussion about natural sources would commence. It was a discussion, however, where a political argument prevailed between two poles: one that considered Tunisia to have many resources, including oil, yet without full control over these resources, and another pole comprising the powers that recalled the founding narrative of the nation state, based on the belief that Tunisia possesses nothing but the intelligence of its people.

In 2013, “Where’s the petrol?”, a campaign led by unemployed young men and political activists was launched to demand that oil drilling figures be shown and that oil company contracts be reviewed. They wanted to unveil the real quantities that the country produces. In other words, the campaign called for transparency. The government then was forced to openly confirm that Tunisia did not have much oil, that it wasn’t hiding any lakes of petrol, saying that they had a mere few thousands of barrels. It reached a point where then President Beji Caid Essebsi told a group of students preparing for their BA exams, “You’re the raw material. You’re the petrol.” As such, he invoked Bourguiba’s theory in response to his political adversaries, who considered “their demand for petrol” to be soliciting a dependent rentier model, which would undervalue diligence and labour.

Bourguiba would repeat that “all Tunisians have is their “raw matter””, by which he means “Tunisian brains” as a means of growth. “Pure Tunisian intelligence” subsequently became a catchphrase among citizens and politicians.

Natural resources are those that have a high exchange and conversion value in the global markets, such as oil, minerals, renewable energy, water, and agriproducts.

Political arguments are raised on natural resources, and the successive post-revolution Tunisian governments are unwilling to delve into the question – for multiple reasons, most important of which is perhaps the legitimization of current economic policies, which are essentially based on tax collection and indebtedness. Nonetheless, the management of the country’s natural resources is what matters, that is, in the context of the limits and conditions drawn by multinational companies that work in both the phosphate and energy sectors. Additionally, one should examine what these resources mean in the context of dependent and unproductive economic models, and how they’re managed in the complete absence of transparency.

What resources does Tunisia have?

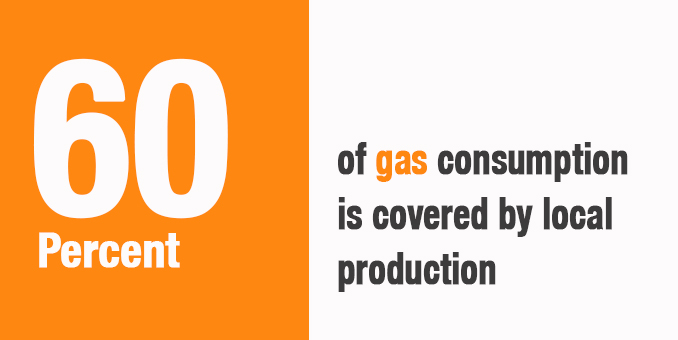

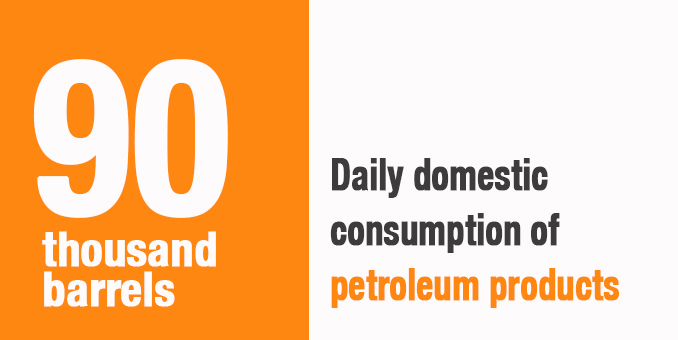

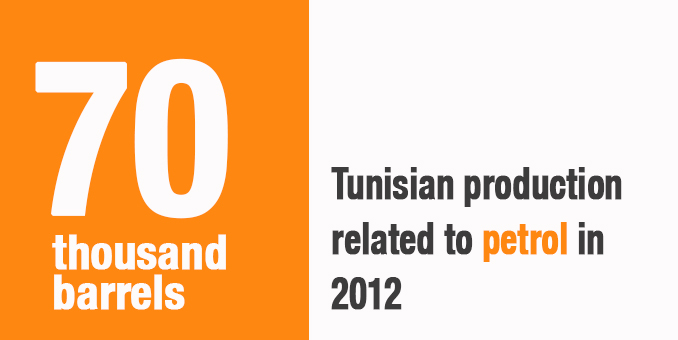

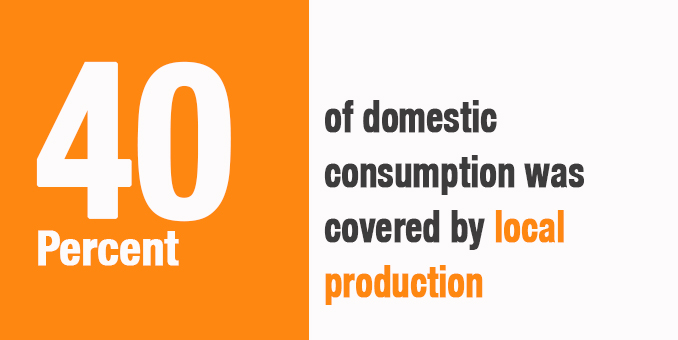

Contrary to the official narrative, and despite the high poverty rates in the country, making up 30 percent of the population, Tunisia does have its own resources. What’s meant by natural resources are those that have a high exchange and conversion value in the global markets, such as oil, minerals, renewable energy, water, and agriproducts. The figures issued by the Tunisian Ministry of Industry indicate that oil-related Tunisian production has reached, during 2012, the limits of 70 thousand barrels a day, and more than 750 oil drilling operations were conducted. Only 115 of those, however, have led to the discovery of exploitable oil wells. El Borma and Ashtart fields make up 85 percent of oil-production in the country, noting that Tunisian petrol is categorised by oil experts as top quality worldwide. In the global market, such production is sold crude, whereas the country itself imports lower quality oil products, to be treated in petrol refineries in Bizerte Governorate and in Skhira city in the Sfax Governorate. For its own internal use, Tunisia requires nearly 90 thousand barrels a day; 40 percent of those are covered by local production, whereas the rest is imported. As regards natural gas, production reaches 56 thousand barrels a day. The British Gaz Company has monopolised the gas production of the Hannibal and Ashtart fields, which covers 6o percent of local production. Algeria provides the rest; some of it is bought and the other is given for free, in return for Algeria’s use of Tunisian territories to export gas to Italy.

Tunisia’s most important resource is phosphate, ranking fifth in its global production. Its main mining fields are located in Gafsa Governorate in the southwest regions, run by Gafsa’s Phosphate Company. Its treatment is then handled by the Tunisian Chemical Complex in Sfax. Between 1998 and 2010, phosphate production in Tunisia reached around eight million tonnes, of which the Gafsa Phosphate Company makes around one billion dollars a year. The phosphate sector stands out for its high employment capacity, which has led the local population to demonstrate and demand their own share of employment, especially following the overthrowing of Bin Ali’s regime.

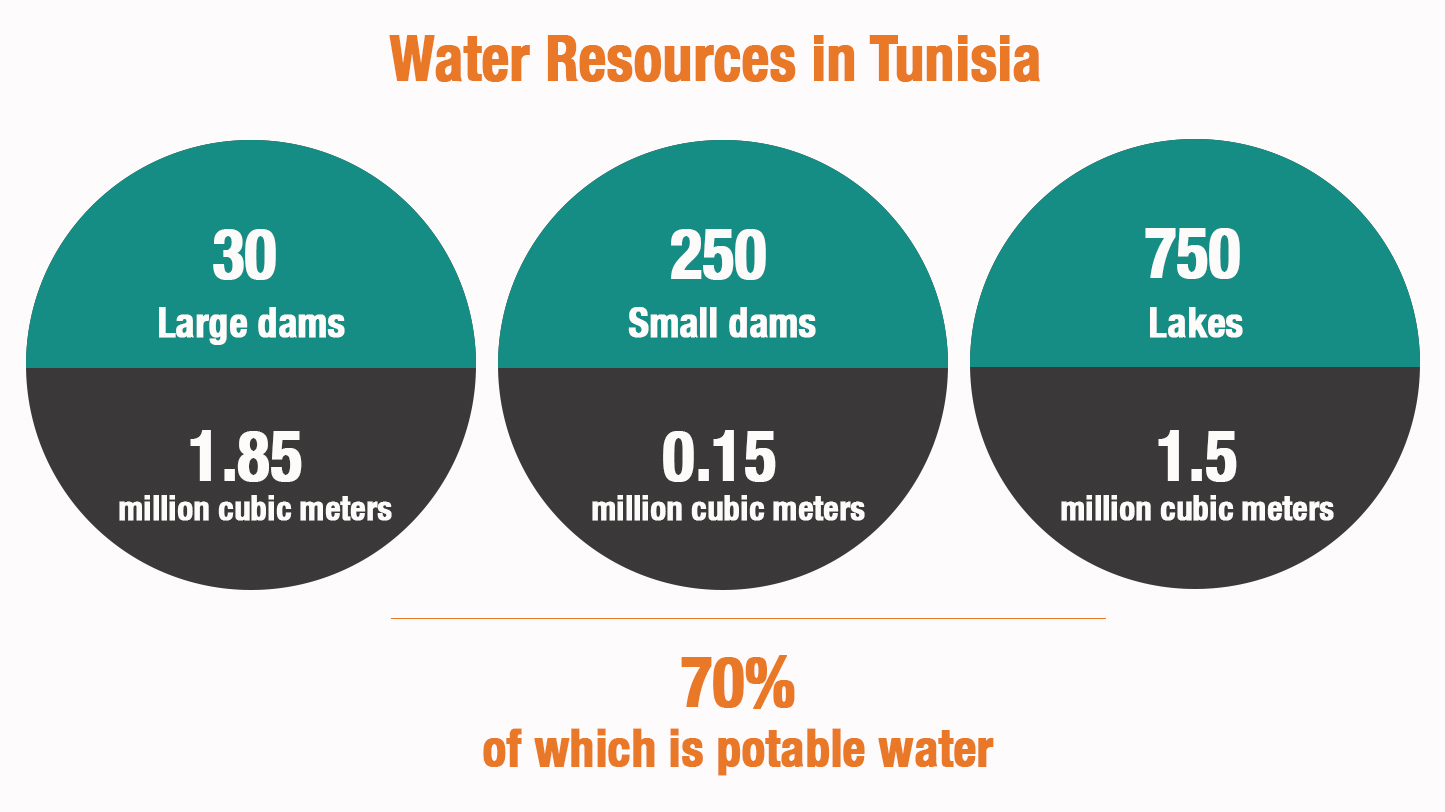

The water resource management has also been quite ambiguous, causing anger and popular protests. Some areas, especially in the country’s inlands, have been suffering from drought, although they are home to the biggest water reservoir in the country (specifically in the northern and central regions). Numbers show that there are 30 large-sized dams with the ability to collect what amounts up to 1.85 million m3 a year, in addition to 250 small dams and 750 lakes that subsequently provide 0.15 million m3 a year and 1.5 million m3 of the water reserve. Such infrastructure guarantees 70 percent of safe drinking and irrigation water. However, the more important question is: how can water resources be distributed, and in which sectors should they be used? Then, what makes Tunisia, despite its large water resources, “always at the risk of drought”?

Then, besides water, petrol, and phosphate, there’s mineral salts and renewable energy.

At the expense of the local population

One cannot resolve the question of natural resources in Tunisia, and in Third World Countries in general, without linking it to the division of labour. That world is based on an industrial core that owns the technology and on the side-lined margins that own nothing but raw materials that they export for a low price – determined by the global stock markets. Economic growth, often brought up in these cases, is usually linked to the revenues generated from exporting primary raw materials, like phosphate, fish, and agriproducts. Shrunken exports mean shrunken growth. However, growth generated from exporting natural resources has failed to realize independent development; development cannot be sustained under rentier economies. Growth is quantitative, whereas development is qualitative, which positively affects the local communities. The Tunisian case reveals that the regions that produce natural resources are the most impoverished and marginalised – like the phosphate-producing Gafsa region and the oil-producing southern regions.

The national economy that took shape post-independence still maintains its precolonial nature; the inlands form a source of wealth, completely geared towards international exports, without yielding any developmental benefits to the local population; rather, the latter is often twice as harmed by such practices. On the one hand, we find high percentages of unemployment among the younger generations; unemployment rates in Gafsa Governorate, for instance, are an estimated 30 percent of the potential workforce – double the national unemployment rate. The same applies to southern regions that live off of smuggling. On the other hand, the local population suffers from pollution generated by extractivism and refining phosphate – especially in the mining basin and in Gabes and Sfax. Media reports have shown in the past few months that the health units in Gafsa city have recoded a rise in chronic and malignant disorders, and damages to the oasis and water reserve as a result of the toxic gases emitted from phosphate treatment plants. In parallel, phosphagen residues have greatly damaged the agricultural sector there. The same applies to both Gabes and Sfax, where the Tunisian Chemical Compound operates.

Additionally, those areas lack good infrastructures capable of counteracting the negative effects of pollution, caused by exploiting underground riches. While government officials have known this since Tunisia’s independence and awareness of the matter has only increased following the revolution, no one wants to change reality. All that governments want is “buying social peace” by transforming what nature gives them into a rentier economic model – through which the governance mechanism is entrenched.

Tunisia’s case reveals that the regions that produce natural resources are the most impoverished and marginalised – like the phosphate-producing Gafsa region and the oil-producing southern regions. This is characteristic of the rentier production model.

The national economy that took shape post-independence still maintains its precolonial nature; the inlands form a source of wealth, completely geared towards international exports, without yielding any developmental benefits to the local population; rather, the latter is often doubly harmed by such practices.

This has manifested in various stages. The 2008 mining basin uprising revealed the irony that the regions that produced natural resources had no shares in them. Ben Ali’s regime cracked down on the uprising then and crushed it. This happened again following the revolution, through similar moves, like the Kamour Uprising in Tataouine Governorate in the south, where young protesters, mostly unemployed, blocked the oil valves and pumps used by foreign companies, demanding that they be employed there. Then, in Kerkennah Islands, violent protests against the British company, Petrofac, broke up against its overexploitation of natural resources and contamination of the sea. Those protests have forced the authorities to look into the questions of natural resources. Rather than rethink its management based on a new and fair developmental model, they opened the door of employment to protesters in “environmental and planting companies” – a formula where the employed receive wages without truly working. The official approach has always faced the contractual pressures of companies, especially those that exploit oil fields or work in excavation, with efficiency and profitability being their main aims; it also faces the pressures of social demands. The governments have submitted to contractual obligations at the expense of the people’s demands, to the point of having to involve the military to protect oil fields during the Kamour sit-in. Some government officials had also demanded a military intervention that would crack down on the protesters that blocked the production of phosphate.

In the absence of clear public policies in their management, natural resources figure as part of the political economy of control. What foreign companies want is more profit, whereas the state wants to guarantee the most “social peace” possible, by way of installing unproductive employment in the sectors related to energy and mining. These resemble social bribes more than they reflect an accommodation of the workforce. Authorities are occasionally forced to address issues integrally, which is often thanks to social upheavals.

“Lobbies” with “tribal” connections and solid politics that know how to benefit from social tensions would be revealed. The transfer of phosphate through privately owned trucks that belong to influential businessmen, who are part of the ruling circles, prospered – that is, following the halting of transport through the railroad networks which were blocked due to protests.

As for energy levels (electricity, gas, and fuel), the official discourse continuously affirms that Tunisia suffers from a huge energy deficit, one that has devoured a third of the state budget – that is, despite the official discourse on increasingly resorting to renewable energy. The government explains such deficit, which continuously forces it to increase fuel, electricity, and gas prices, and link them to the global increase of oil prices and the halted production of phosphate. However, in parallel, the energy-related cases of corruption are sealed with silence while, in the best of cases, they are dealt with through scapegoating junior officials.

Corruption and grey zones

The case of the secretary of state responsible for energy in the Youssef Chahed government, who accepted bribery in return for an Iraqi businessman’s control over a fertilizer deal from the Gafsa Phosphate Company, has uncovered the way natural resources are handled. The secretary of state was thus imprisoned and the minister resigned. Prior to that, the government spokesperson announced that one of the investors had invited the head of government in 2018 to inaugurate an oil well in the coastal Monastir city. In turn, the investor appears to have unduly exploited the field since 2009, noting that the overall value of the field production was estimated at nearly 15 million barrels a day. The minister was thus dismissed and the case would be investigated.

El-Sissi and Resource Management in Egypt

27-03-2022

Morocco: A Kingdom of Rent

18-04-2022

In 2019, in a similar context, the accounting department report showed that more than 11 million dinars was the cost of free energy given to those who owned the Tunisian Company for Electricity and Gas. The report showed that the state has no national strategy to regulate energy, contrary to what the national agency of this sector claims. The data also shows that the declining production of phosphate isn’t necessarily connected to the social pressures (that is, the demands-based movements) that the company faces but to the corruption that infiltrates the Gafsa Phosphate Company, which is outright financial corruption. Most importantly, however, is that phosphate production also perceives companies as spoils, which is exactly the ruling party’s approach in Ben Ali’s era.

Money would be obtained from the company under fictive pretexts, such as funding sports, in addition to a delegation policy based on nepotism, all while constantly looking to balance partisan and tribal logics. After 2011, several “lobbies” - with “tribal” connections and solid politics can be employed to benefit from social tensions - would be revealed. The transfer of phosphate through privately owned trucks that belong to influential businessmen, who are part of the ruling circles, prospered – that is, following the halting of transport through the railroad networks which were blocked due to protests. Natural resources are a field where lobbies and financial powers assemble.

The state gives up its resources: to whom?

Ever since Tunisia adopted the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), natural resource management has been rethought. It was decided that the public authorities would be encouraged to directly manage them – to the benefit of private investors. One of the results of such a decision, for instance, was giving up four factories specialised in grey concrete production in 1998. The Tunisian Industrial Concrete factory was given to an Italian company, the Central Mount Concrete to a Portuguese compound, the Enfidha Concrete to a Spanish compound, and the Gabes Concrete Factory to a Portuguese compound, while a white concrete factory was given up to a Portuguese compound. That same policy was applied to the water resource sector, where the state gave up water management to benefit the Agri-development Compounds, composed of private elites. The slogan raised during this process was “supporting a participatory approach,” while the result on the ground was more corruption in those compounds and further waste of water resources due to their malmanagement.

This takes place at the expense of small-scale farmers. In that context, the state has given long-term contracts to oil exploitation and drilling companies – however, all data indicates that the contractual relationship between the state and those companies lacks transparency, and that no one knows how exploitation contracts are given. Even legislation in that regard seems ambivalent.

Lack of public policy on natural resources renders the latter at the mercy of political bids, making it a playground for corruption and favouritism. Corruption here does not contradict with global capitalist agendas, which relentlessly seek increased profits.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 26/07/2019