This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Right after Mohamad Bouazizi burned himself in front of the Sidi Bouzid Governorate, and at the start of the December 2010 protests, the Tunisian Islamists were still in prison, while some of their leaders were keeping a close eye on the events from the European capitals where they had been exiled. At the time, the Islamists hoped that Ben Ali would undertake reforms that would grant more political freedoms so that they could be released from the prisons or return from their diaspora. They were not aiming for the fall of Ben Ali, but were only seeking recognition. Like the opposition parties, some of which are leftists, the Islamists had reformist and conservative tendencies. Concomitantly, in the streets, the demonstrators were chanting for the fall of the regime with the slogan “Bread and water and no to Ben Ali!”

Almost everyone agreed (and still agrees) that the revolution lacked a leadership and a clear ideology. This may be true in some ways, but whoever has lived in proximity with the events cannot deny that the leftist organizations such as the “General Union of Tunisian Students”, activists from the radical left and professional unions affiliated with the “Tunisian General Labor Union” were at the forefront of the protests and marches, even though this does not mean that the left had planned the uprising or overthrew the regime.

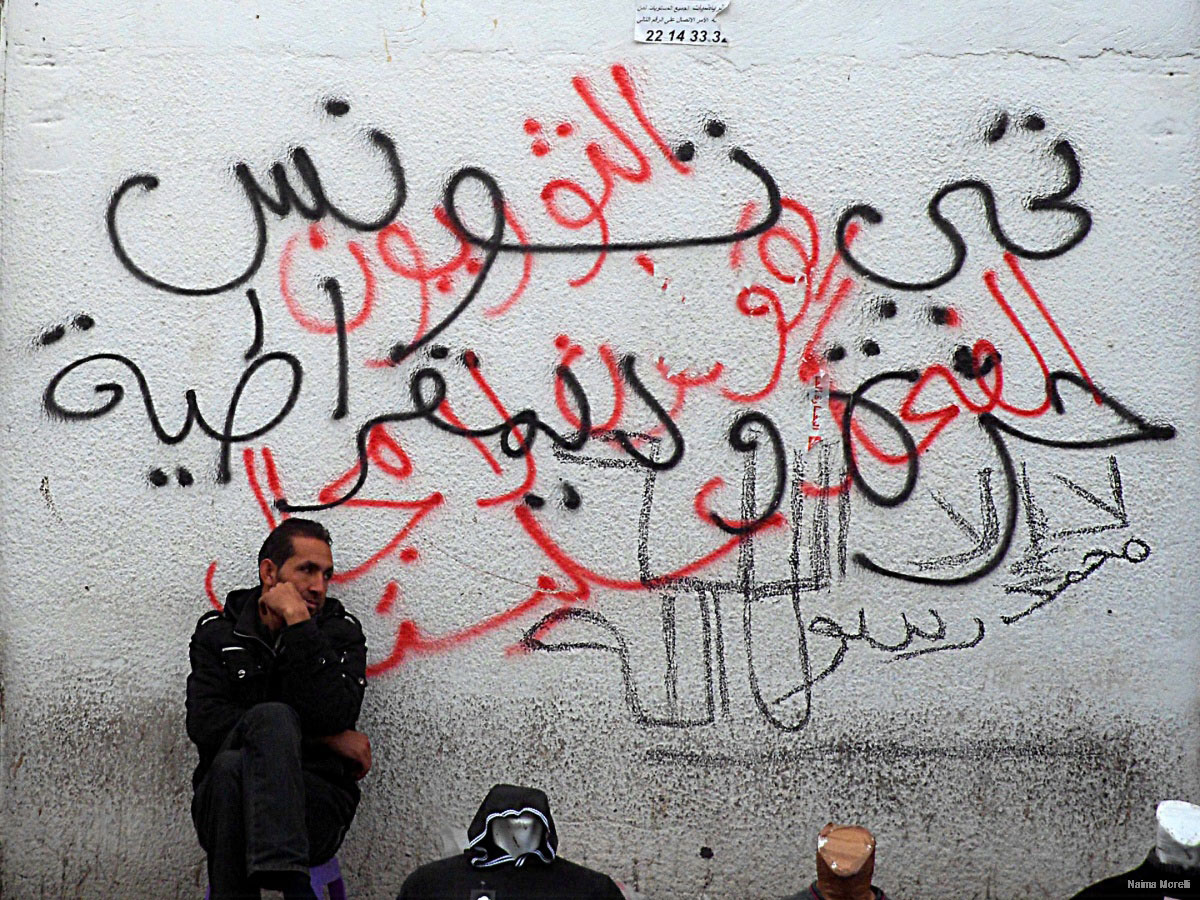

The “January 14”moment had the features of a “leftist moment” in terms of its demands and slogans related to employment, social justice and national dignity. Slogans with an Islamic reference were nonexistent at the time and all that the protesters were calling for was the departure of Ben Ali. In addition, the demonstrations did not start from mosques but from universities and unions’ headquarters.

Nevertheless, the Islamists eventually came to power while the “left”(in all its different currents) remained outside of the electoral calculations. A closer inspection of the issue reveals that the left-wing organizations, movements and groups have failed to find a place within society, and to root themselves in the sectors that were supposed to be their social incubators, such as the popular neighborhoods located within the cities and urban outskirts, while the “Ennahda Movement” had established its presence in these spaces since the eighties of the last century. That was until Salafist jihadism succeeded in attracting the youth of those neighborhoods after the revolution.

Urban margins turn their backs on the left

During the elections for the Constituent Assembly in October 2011, the parties of the left only won a small percentage of the seats, not exceeding ten percent of the Council. The majority of the seats were won by Ennahda Movement. The scenario repeated in the 2014 elections, which brought back the old regime’s remnants embodied by “Nidaa Tunis” to the forefront of power, before it disassociated with the Ennahda Movement and self-fragmented. Ennahda had a slight retreat in the 2014 elections and ranked second behind Nidaa Tunis. However, Ennahda managed to remedy this setback in the municipal elections where it won by a majority. The left, represented by the Popular Front, remained in the same position, winning not more than ten percent of the overall seats.

The “January 14” moment had the features of a “leftist moment” in terms of its demands and slogans related to employment, social justice and national dignity. Slogans with an Islamic reference were nonexistent at the time. The demonstrations did not start from mosques but from universities and unions’ headquarters.

The strength of the Islamists stems from the fact that they are strongly rooted in popular neighborhoods, city margins and in some regions of southern Tunisia, characterized by conservatism and a historical tension with the central authority. Islamists do a rather good job positioning themselves in the gaps abandoned by the welfare state. These gaps had widened after the “Democratic Constitutional Rally Party”, that had previously played the role of the watchtower and mediator between the state and the margins, dissolved itself. In exchange for providing some social services and aid, a relationship of clientele was formed that assumes loyalty to the ruling party, that is, to the existing system.

Ennahda Movement took advantage of these same mechanisms and reproduced them, relying on the policy of proximity and its control over a large number of mosques. Only Salafist jihadism rivaled Ennahda in these policies. There are differences between Ennahda Movement and Salafist jihadism at the level of the political practice and the sociological structure but they meet in their interest in social issues (poverty, unemployment, work precariousness, etc.) to establish roots in the urban margins that are left to manage and survive by themselves.

Since the 1980s, the state has worked to “integrate” those neighborhoods, particularly the slums, through a policy of urban development and polishing, connecting them to sewerage networks and public lighting. But that policy had its limits as it was unable to diminish the feelings of stigmatization, injustice and anger that were growing within those geographies. Evidence of this is that protests that erupted since the revolution (and even before it) usually had an urban character and were mainly concentrated in the areas listed in the “bottom of the hierarchal system of places” (the phrase is for the French sociologist Loïc Wacquant).

These are places where the presence of the state’s social welfare is minimal while its security presence is overwhelming. This pushes the inhabitants of those places to sustain the sense that their image in the official representation lies mainly in their categorization as “dangerous classes” that must be controlled primarily on a security level.

At the same time, Islamists worked silently. They went “underground” in the times of repression, relying on traditional solidarities, family networks and community solidarity (belonging to the same neighborhood or alley). Their leader, Rashid Al-Ghanouchi, considered that the revival of Ennahda was “a return from the underground”. The welfare state was not the only one guilty of ignoring the "margins", whether in the cities or in the remote rural areas. The modernist and secular elites, including the Tunisian left, were also completely absent from these spaces and showed ignorance about their real conditions.

Islamists do a rather good job positioning themselves in the gaps abandoned by the welfare state. These gaps had widened after the “Democratic Constitutional Rally Party” dissolved itself, even though it had previously played the role of the watchtower and mediator between the state and the margins through the clientele mechanisms. Ennahda Movement reinforced its presence by using those same mechanisms and through its permeation in the fabric of charitable associations.

After the revolution, the presence of Ennahda was reinforced by its permeation in the fabric of charitable associations working to provide aid to the poor population of the popular neighborhoods and to the impoverished internal regions. Thus, the clientelism that the ruling party had built was replaced by a new one. Salafist jihadism has worked firmly and effectively with that same logic, succeeding in attracting marginalized stranded young people lacking purpose, providing them with financial aid and creating small jobs for them, often in the informal economy sectors. This made the youth feel that they belonged, and that there is a bond linking them to a group. In this regard, Islamists, in all their various groups, realize that social ties are the gateway to political action.

They realize that they are moving in a society that still “claims” - at least - its adherence to its traditional values (which have become the last social lifeline) that pay great attention to community solidarity and familial cooperation. They also realize, perhaps more importantly, that the dislocated and loose side of these traditional values is offset by the complete absence of any alternative system (in belonging to a workspace, for example, which creates a social medium, or even in the state’s recognition of the citizen’s individuality and rights). The provision of relational frameworks, whatever they may be, becomes a decisive existential matter that is of a great importance and weight, which is not the case in the stable established societies in all their different forms.

The Islamists are also working to establish a conflict between “the people” and “the elites”. The latter are those groups that are educated and fully integrated into the urban world, and which oppose the Islamic project as an identity project. It is precisely because of this that Hammadi Al-Jebali, one of the leaders of Ennahda and the former Tunisian prime minister, considered that “our elite is our affliction”, because according to his perspective, the elites oppose the identity aspirations of the people.

Where is the left?

The left - whether that of the “Popular Front” and some other neighboring parties, or that other “civil” one represented by some left-wing and human-rights associations, is in a spacial schism with the urban margins and the “geographies of anger”. It has no presence on the ground, on the political and ideological levels, due to several factors. Perhaps the most important of which is that the left-wing theses are still approaching reality from theoretical and intellectual perspectives which do not take into account what is actually happening. The people’s “voice” is not being heard and is not being understood and adapted into political plans and programs.

On the other hand, the left seems to be closer to the middle classes, which is the official doing of the independence state, and a close look at the sociological composition of left-wing organizations reveals this. It does not mean, however, that the Ennahda Movement members and leaderships do not also emerge from these same middle classes. However, the movement is characterized by the dominance of craftsmen and workers, within its popular bases, who work in the parallel and informal sectors of the economy. On the other hand, most of the components of the leadership and the bases of the left are secondary school teachers and government employees, and a few are doctors or small businessmen. Perhaps the paradox is that although the middle class within which the left is moving is in a constant decline, it remains essentially concerned with the values of economic welfare and freedoms. At the same time, it is urgently concerned with improving the conditions of its existence in the context of its ability to negotiate with the regime. Therefore, when the battle intensifies on social issues, most of the leftist parties and components in Tunisia line up behind the “Tunisian General Labor Union”.

This indicates, on the one hand, the strength of the unions and their ability to mobilize but, on the other hand, it expresses weakness in the parties of the left their elites that seem to ignore the logic of political strategizing and are still drawn to the opposition’s narratives, as if they were refusing to come to power.

The left - whether that of the “Popular Front” and some other neighboring parties, or that other “civil” one represented by some left-wing and human-rights societies, is in a spatial schism with the urban margins and the “geographies of anger”. It has no presence on the ground, on the political and ideological levels, due to several factors; most important of which is that the left approaches every problem with ideological preconceptions.

The forces of the left do not operate in the geographies of the margins (the popular neighborhoods and the rural areas). The left has not succeeded in formulating a discourse which the marginalized groups can identify with, including those who are excluded from the worlds of work and consumption, or those that are part of the informal work sector or at its margins. The hackneyed speeches from the left’s leaderships about the “Zawali” (the destitute) and the “sons of the barefoot” (the sons of the rural women) do not contribute to any change, but rather, this discourse belongs to the ongoing state of objections that characterizes the left’s parties and its popular bases. The ironic thing is that the more the left excels in producing a discourse about social justice, poverty and marginalized areas, the more its influence in the course of events is revealed as limited.

This is why the marginalized people in Tunisia do not see the “left” as the political alternative that would accommodate their hopes, not only for cultural reasons, but because the visions and insights of the left’s elite do not “reach” them. There are several reasons why the two remain disjoint, one of which is the obsolescence of the discourses of the left which still perceives social conflict through the lens of social classes and structures that no longer exist. The left’s discourse has been bypassed by a neo-capitalism based on globalized cash flows and financial markets.

The leftist rhetoric grants no real importance to the dimensions that the groups most affected by the dominant neoliberal economic policies have come to relate to and speak about: the desire for respect and recognition and the avoidance of contempt. Those in the middle class who are quickly spiraling downward and the “marginalized people of the cities” do not aspire for the overthrowing of the regime. What they essentially want is participation in the system, i.e. to be like the others, on the basis of equality.

Rap in Tunisia: Art or Resistance?

20-10-2013

Consequently, the new forms of social conflict are no longer determined by the logic of a clash between the classes, but rather by the logic of the distance that separates those people from the others who are fully integrated into the consumerist society. The prevailing fear is, in fact, a fear of exclusion. During the protest movements in which left-wing leaderships are involved, the slogan “Down with the regime” is raised, but only as a tactical slogan. The marginalized do not really want to topple the regime. Rather, what they are seeking for is a place in the regime that would allow them to have their share of benefits.

But is this possible? Is it not one of the tasks of the left, to question the very foundations of the dominant political economy and the policies of control and injustice in Tunisia, rather than developing subservience to the overriding reformist trends in the country?

The new left: Retrieving the margins?

Most of those who are part of the so-called “New Left” are young people who had had some kind of partisan leftist experiences in the past, but had soon withdrawn when they sensed that their individualism was obliterated by the tyrannical tendencies of the leadership. The younger generation holds an extreme apprehension to the patriarchal and commandership dispositions that characterize the partisan left in Tunisia. It is an organizationally undemocratic left, as the determinant factor according to this left is not always democracy, but the militant and historical legitimacy. Hamma Al-Hammami has led the Labor Party for thirty years (the same goes for Rashid Al-Ghanoushi and Ennahda Movement). It makes no sense to negotiate new names or to give way to any new faces, and this process has rendered the left senile and unable to regenerate across generations.

Although the middle class within which the left is moving is in a constant decline, it remains essentially concerned with the values of economic welfare and freedoms. Therefore, when the battle intensifies on social issues, most of the leftist parties and components in Tunisia line up behind the “Tunisian General Labor Union”.

The case is not that the new generation is “reluctant to join politics”. It is a generation that has a strong individualistic tendency and favors new forms of militant commitment. This is precisely what distinguishes youth movements such as “Fesh Nestenau” (“What are we waiting for?”), “Manish Msemeh” (“We shall not forgive”) and “T’allam ‘Oum” (“Learn how to swim”). Most of the members of these movements are university students, school students and amateur artists, most of whom have lived through the events of the revolution. They were born in the mid-1980s and early 1990s, and are well-acquainted to social media which they use on a continual basis. They do not present themselves as leftist militants but as “activists”, yet they consider themselves “comrades”. These young people are usually not religious and they are part of the urban consumer world, somehow liberated from the traditional social and moral constraints.

They were able to form a political dynamic and a presence in the public spaces through their work on specific problems: the reconciliation law for the “Manish Msemeh” movement and the financial law for the “Fesh Nestanau” movement. The “Manish Msemeh” movement was lenient in some sense, as its criticism of the authority did not exceed protesting the law of reconciliation with corrupt businessmen, and it was unable to expand the scope of its protests or to give it a political content, while the “Fesh Nestanau” movement adopted a more radical approach, as a reaction to the finance law with its injustices towards the poor and middle classes. This exposed the movement to oppression, especially since it succeeded (relatively) in mobilizing part of the youth of the popular neighborhoods. The protests were violent and had many political and social implications. They ended with a confrontation with the police, especially in the slums adjacent to the capital (the January 2017 protests).

Nevertheless, the two movements subsided and did not last very long, especially since they were both based on specific issues or transient occasions. These are movements that do not offer themselves as continuities in the first place and do not seek to assume the responsibility of formulating a political vision on the basis of clear programs and goals. Fragmentation and transience characterize such movements which restructure themselves in an inconsistent manner and therefore become less effective or temporary. This is in clear contrast to the political Islamic formations that can only operate in permanence and continuity.

The Realities of the “Left” in Morocco

01-03-2020

In the end, perhaps what makes a difference between the “Ennahda Movement” and the rest of the leftist forces, mainly in their relationship with the urban margins, is that the former is politically engaged in these spaces and views them as a political wager that should not be neglected, while working diligently to expand the scope of its work towards other classes and sections. This is what the left lacks in both its partisan and civil wings.

It remains torn between partisan activism centralized in major cities and excessive elitism while abandoning the margins. The absence of leftist parties from the margins is not only explained by the fact that the poor classes “are not prepared” for leftist ideas, but, ironically, it lies in the fact that those spaces have remained outcast from the political perceptions of the left-wing forces.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 18/01/2019