This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

It has long been assumed that women are more suited for work in textiles and clothing factories. It’s a type of work that socially conforms to the existing gendered division of labour -or falls within its vicinity. The presumed feminine obedience and ability to carry out repetitive and routine tasks were transferred from the realm of the domestic into that of the factory. Since the 1980s, Tunisia has been witnessing a remarkable increase in the number of female workers in the textile industry.

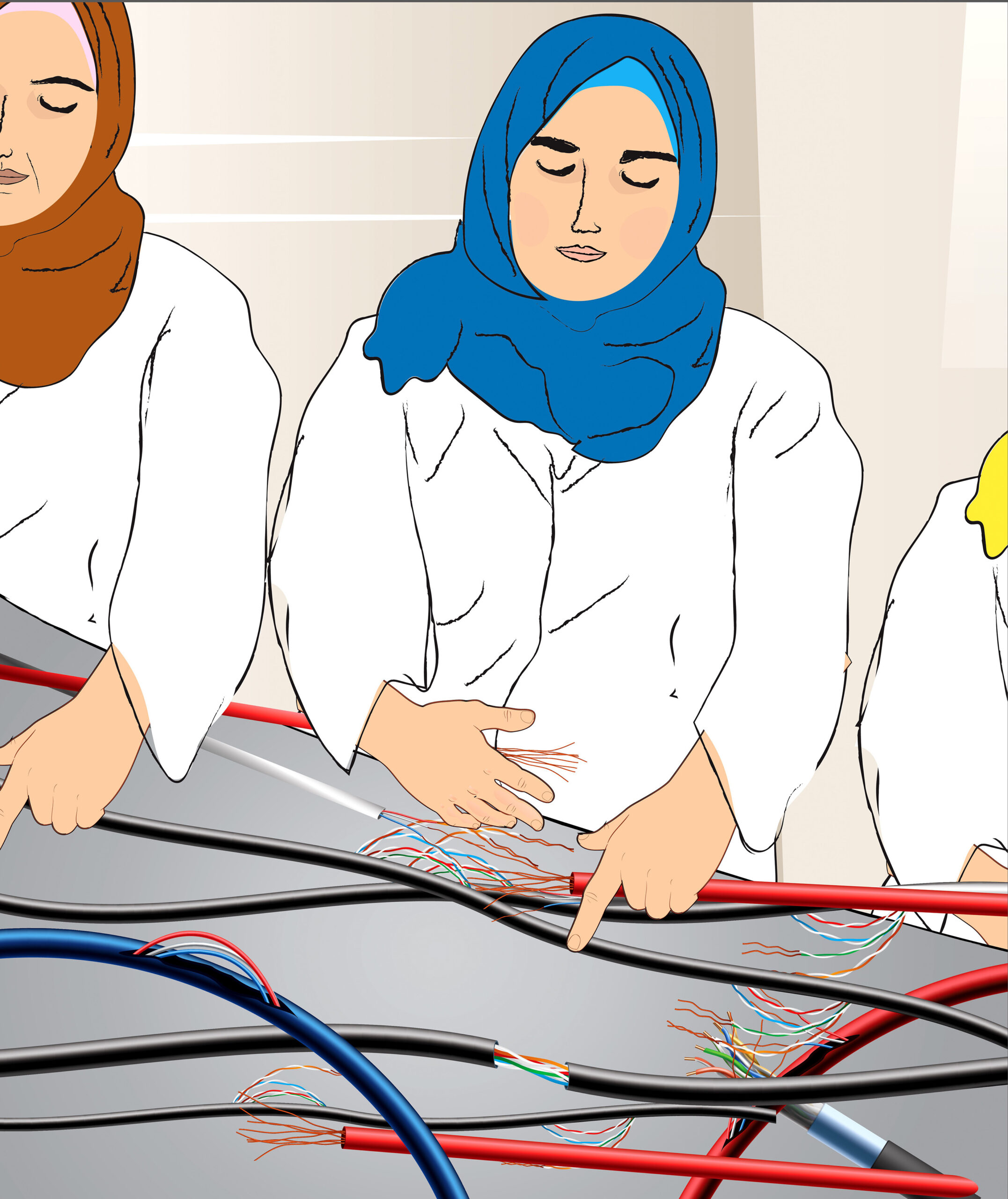

Tunisian women have also been integrated into the heart of some industries that were traditionally categorized as “manly”. The phenomenon of feminization of industry has gone beyond the textile and clothing industries, and now reaches different types of manufacturing, like the manufacture of wires for cars and heavy trucks, as in the Japanese Yazaki factory in the city of Gafsa in southern Tunisia. In fact, the factory itself has devised a recruitment strategy that targets and seeks female labour.

Yazaki Factory

Founded in 1929 in Tokyo, Japan, the factory supplies a wide range of products to more than 45 auto manufacturers. It employs more than 260,000 people worldwide with branches that span more than 47 countries, including in the Bizerte and Gafsa governorates in Tunisia. The Yazaki Factory, located in the Aguila Industrial Zone in Gafsa, employs 1678 workers, 1131 of whom are female workers.

To understand this sociological paradox, we rely on the reasons female workers provide for working in the Yazaki Factory - a factory in which women make up the vast majority of workers in an otherwise male-dominated industry. These responses shed light on the social justifications and the rationale they provide for choosing this place of work.

Work or education?

One of the main factors in the feminization of the Yazaki Factory is the modest educational levels of the female workers. In fact, one of the qualifications for joining the factory according to the employer’s policy is that: "the educational level of female workers must not exceed a bachelor's degree." This precondition is enforced during job interviews and aims to justify the meagre wage, which does not exceed 350 dinars per month.

The number of workers in the Yazaki Factory, located in the Aguila Industrial Zone in Gafsa, is 1678 workers, 1131 of whom are female workers.

Female workers compare the cost of continuing their education or staying home on the one hand, with the benefits of factory work on the other. This ends up pushing young women in this neglected and impoverished region of Tunisia to drop out of school and chose the workspace over the domestic space. The majority of these women are usually between the ages of 19 and 27 years and come from working class and sometimes middle-class backgrounds from all over the Gafsa region.

When asked, female workers cite the country’s fragile economic situation and the failure of state institutions to employ university graduates as some of the justifications for their choice. One worker said: “Even if I could go back in time, I would still choose to work. The situation in the country is still as it was when I was studying French and decided to quit. A friend of mine has a master’s degree in Arabic Literature and she has not been able to find work yet. Look at me, I may have dropped out of school, but, unlike her, at least I am working.” Another worker commented, “Education does not help you get a job. That’s why everyone is unemployed”.

For these women, academic spaces have become repulsive; a risky investment of time and energy and a route which does not guarantee job opportunities. They have even come to see university as an obstacle to finding a job, since the majority of the unemployed have university degrees!

The factory, on the other hand, does not require much. A worker simply needs to be healthy and have a minimal level of education.

Some of the main requirements imposed by the employer on female workers are that their “level of education not to exceed a bachelor’s degree" and that they are young. The majority of female workers fall between the ages of 19 and 27.

In Gafsa, the urgent need to make money is linked to the absence of job opportunities or development projects, a high unemployment rate, and the aspiration among young women to achieve financial independence. A woman’s wage protects her against the authority of the man or of her husband; an authority which comes largely from his status as a “provider” for her in the framework of the family. If she brings in some money, she can take care of her own needs without the help of a man or a family. One of the workers commented, "Thank God, I was able to accomplish many things because of Yazaki. I built my house and got a driver's license. I live my life, I have my salary. Asking for money never feels good.”

A gendered division of labour

The division of labour at the Yazaki Factory is based on gender. Women’s tasks are typically winding wires, coating them, and installing small wires into car parts. These tasks require both patience and focus. They are also repetitive and quite monotonous. In reference to this, one worker said: "Women are more disciplined than men. This type of work requires the attention span of a woman, not that of a man. We, women, are more diligent than men".

These are the types of jobs and tasks that men tend to avoid. One of the workers comments: “Men get anxious or bored with such tasks to the extent that they are willing to argue with their bosses just to change their posts in the factory,” unlike women who accept doing these types of tasks. Even here, women have transformed an internalized domestic obedience into an obedience to the machine and the employer at the Yazaki Factory. “Women have endurance. They are willing to sacrifice more than men are. They are forced to accept such tasks, otherwise, they would stay at home.”

Female workers have come to see school and university as obstacles to finding a job, since the majority of the unemployed have university degrees!

The division of labour in the Yazaki Factory reproduces stereotypes about women's work as secondary and of less importance than that of men. Women’s work is characterized as simple, easy to perform, and in line with their physical nature and gender identity, as opposed to men’s work, which requires a great deal of mobility, physical strength, and takes place within more sensitive areas in the factory.

Algeria: Fatima M. Is a “Stay-at-Home” Woman

09-10-2022

Tangier’s Women of Cloth

28-08-2022

One of the unexpected byproducts of the feminization of the workspace has been a tension between female workers that come from different socioeconomic backgrounds, sometimes leading to disputes, conflict, and flare ups. This has led to 276 female workers being subjected to first-tier penalties, i.e. being questioned, and 17 others to second-tier penalties, i.e. expulsion.

Women’s tasks are typically winding wires, coating them, and installing small wires into car parts. These tasks require both patience and focus - skills that are attributed to women.

Among the reasons for penalties and expulsions are problems that relate to fighting over male co-workers. Particularly since the majority of female workers are young, and 738 out of 1131 are single. Moreover, for female workers, getting promoted or improving their work environment is not based on their competence, but rather on the personal relationships they manage to forge within the factory, that is, by engaging in personal and romantic relationships with their supervisors. This is a conscious strategy followed by some female workers in order to improve their standing. At the Yazaki Factory, women are exposed to harassment, including sexual harassment. Describing this phenomenon, one worker said: "Behind you, in front of you, to your right, to your left...Everyone is harassing you." Of course, sometimes female workers are complicit.

For the female workers, getting promoted or improving their work environment is not based on their competence, but rather on the personal relationships they manage to forge within the factory, that is, by engaging in personal and romantic relationships with their supervisors.

Finally, there is the issue that the women workers in the factory are not affiliated with any union, as women at the Yazaki Factory perceive unions as organizations whose work and activities are linked to conflict, friction, and strikes. But these women are only given a choice between accepting the situation and remaining silent or getting fired. This is particularly true since 520 of the total female workers are employed without work contracts and are afraid to lose their jobs, especially since the factory is foreign-owned and management “does not tolerate strikes that disrupt production.”

Precarious and cheap female labour

Although it may appear that the feminization of labour at the Yazaki Factory reflects the phenomenon of women breaking into the workforce, it still falls into the category of precarious work. Wages are low, and the work does not provide stability, as the majority of women workers have short-term contracts (one-year contracts), and can easily be laid off. The fact that the factory employs cheap labour without offering stability or a chance for professional promotion means necessity is at the core of these women’s relationship to work. They take up the job to fulfill their many responsibilities, including supporting the family for married women, and for single women, purchasing the marriage trousseau and paying back their debts. Even when the women at Yazaki try to make more money through an informal side business -usually selling cosmetics and perfumes, that work is also precarious, unstructured, and with little economic return.

Conclusion

Today, Tunisia is witnessing the feminization of many of its work sectors, but this feminization is marked by a multiple precarity, in terms of wages as well as working conditions and rights. As the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu says in his book, Masculine Domination, spaces and positions which become feminized also become less valued by society. In any case, in precarious work sectors that have a large number of female workers, contracts -if any- are usually "limited work contracts", which is a way of keeping women’s work marginal and underestimated.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Serene Husni

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 26/03/2020