This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Since 2020, Morocco has been attempting to obtain its own share of vaccines directly from their manufacturing countries. In a global climate of uncertainty, and a race for this substance presumed to provide a way out of the dreary Covid-19, competition has been shaped around who pays more, who pays whose accounts, and who is willing to give up in return for a vaccine quota.

In the Moroccan case, not many details have been fully revealed, except that Morocco was able to contract several manufacturers relatively early, perhaps most notable of which is Sinopharm in China. Moroccans, however, were initially uncomfortable with the vaccine, as it aroused much scientific controversy and popular doubts and fears around its efficacy.

Pre-vaccination: Fear of Sinopharm

In November 2020, Morocco launched its vaccination campaign, after contracting the British-Swedish company, AstraZeneca, and the Chinese pharmaceutical lab, Sinopharm. 65 million vaccine shots would thus be bought, to be sent to Morocco in batches and vaccinate 80 percent of the population, estimated at 36 million people.

This step, however, has been repeatedly deferred, due to growing competition and global demand over vaccines in general, including the Chinese vaccine, Sinopharm. Approval issues have further complicated matters, as the vaccine had to be first tested for safety and efficacy.

During this waiting period, which lasted around two months, most Moroccans started questioning the Chinese vaccine, Sinopharm. They branded it as a “mysterious” medicine from an Asian country, whose full vaccine details were yet to be revealed. Generally, Moroccans’ comments showed concern; they considered the vaccine to be a tool to “control” and “conspire against” them –by “plugging” or “planting an e-chip in their bodies”, one way or another– or even to cause some genetic mutations, instigated by “major Powers” and their giant institutes.

On the other hand, such fear and exaggerations have aroused some other Moroccans’ derision. They believed that the issue should be understood and espoused beyond such discourses of “Facebook sorcery”, as the question requires a thorough examination of the available scientific information.

The discussion then reached scientific circles. Aziz Ghali, expert pharmacist and President of the Moroccan Association for Human Rights, was one of the global voices that expressed doubts and backed public concern over vaccine efficacy. Ghali saw that there was an “information blackout” on the findings of the vaccine’s second and third clinical trials. He confirmed that “the problem does not lie in the vaccine’s side effects, but rather in the extent of the protection it provides”. He explained that the major scientific journals did not discuss the “Chinese vaccine, as data has been insufficient; such information blackout creates fear, especially since the trials held in Morocco were done so over healthy people. The vaccine, however, would be administered to people with health issues or vulnerabilities, as well as to older people. This raises questions about the vaccine’s effectiveness and calls for slowing down.”

In parallel, many scientific voices were raised to “reassure” Moroccans and affirm, through many media platforms, that “this vaccine poses no risk” and that, although it has an 80 percent efficacy only, “has been tried in many countries, with no hazard noted to have endangered the safety of those vaccinated”. Minister of Health, Khalid Aït Talib, however, affirmed that side effects only affected a small number of the clinical trial volunteers in Morocco, whose overall number was 600. He also added that such side effects were limited to “light symptoms, like injection-site itching, high temperature the first day, or dizziness”.

During the past seven months, the vaccination campaign in Morocco has been adequately smooth and well organised. Exceptions to the rule have been a few technical issues lately caused by the mounting pressure on vaccination centres, as more groups became eligible and turned out for vaccination.

Vaccination in Morocco is free and administered all throughout the country, without exception. In principle, in order to control the viral outbreak, vaccine priority is given to cities and provinces more contaminated than others. However, no official data shows that such a standard has been respected all throughout the past months.

In January 2021, after media platforms broadcast King Mohammed’s VI first vaccine shot, such concerns and doubts gradually subsided among the general Moroccan public. Some of the doubtful and fearful thus changed their mind; to them, so long as the country’s ruler has so confidently taken the vaccine, such a step should not be shrouded with so much doubt.

The vaccine rollout thus begins

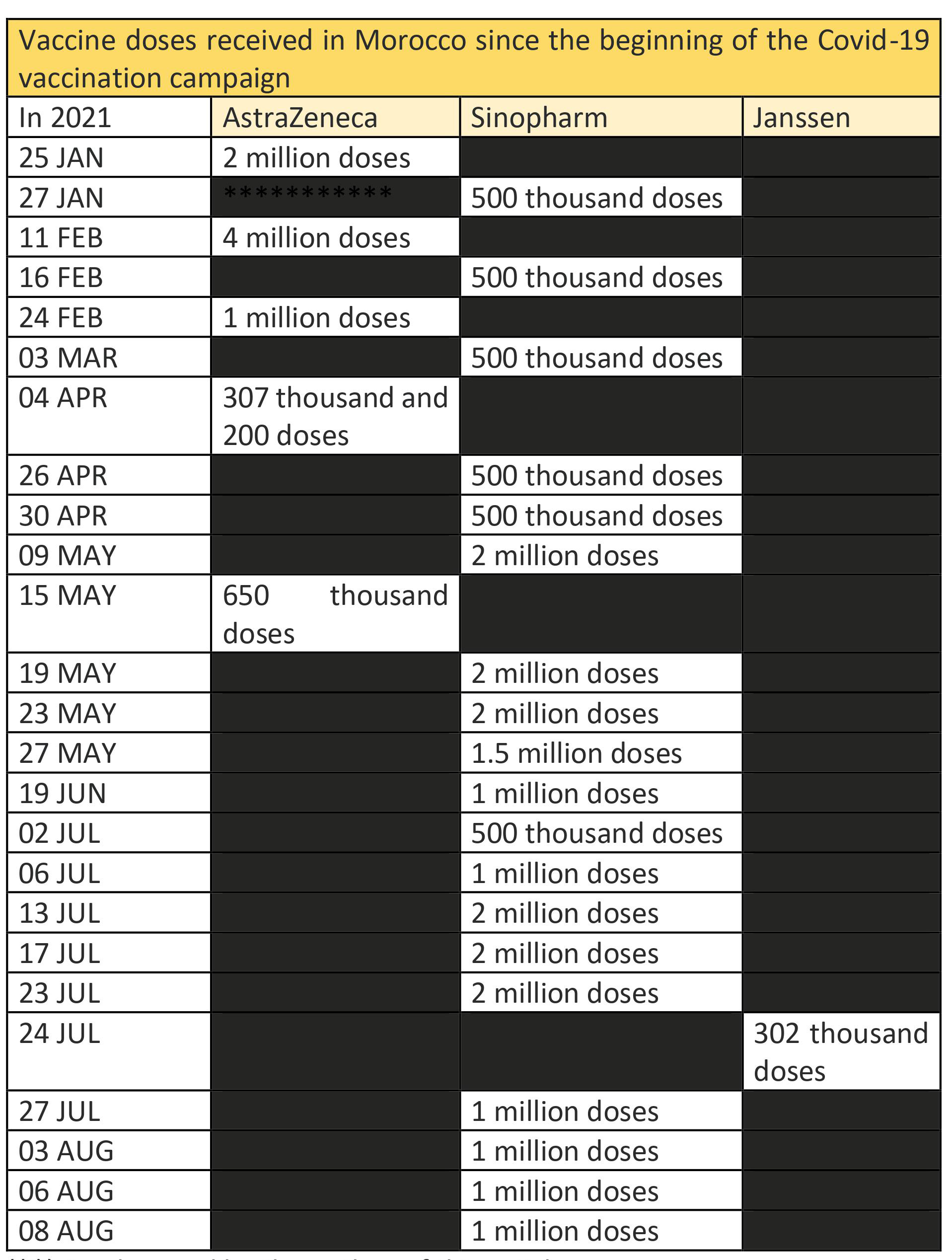

On January 22nd, 2021, Morocco received a first shipment of two million doses of the British-Swedish AstraZeneca vaccine, distributed to all Morocco’s cities and provinces. The vaccine campaign was then rolled out, and the Ministry of Health called for 24 thousand of its healthcare cadres to work in more than 3 thousand vaccination centres and mobile units, half of which were set up in rural country. One could then e-register through a website set up for this purpose, or send an SMS with their own national ID number. They would then be shortly informed of address of the vaccination centre and the date their first dose is planned. In case of communication difficulties, residents of remote areas are informed through Ministry of Interior employees and representatives in villages and towns.

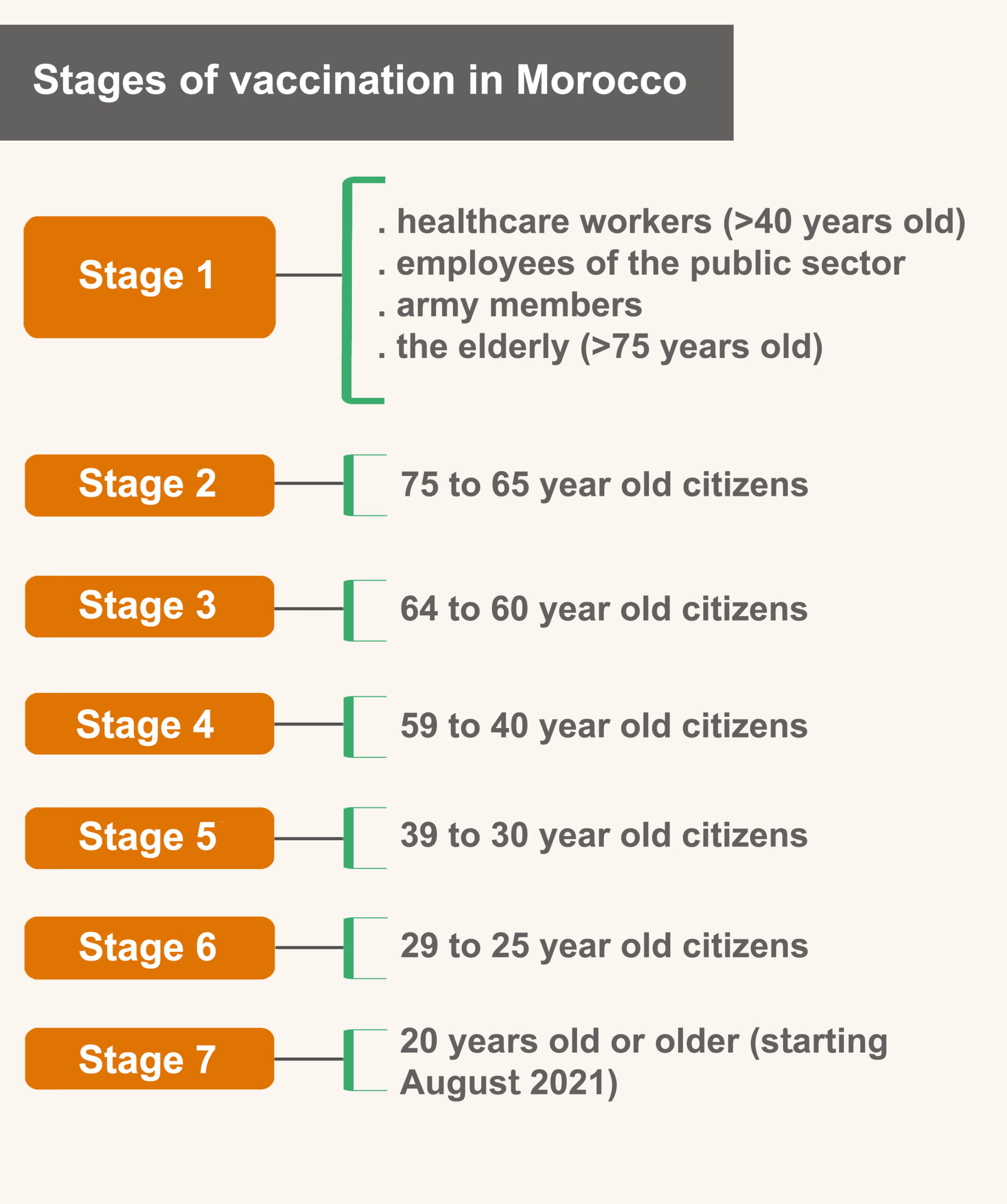

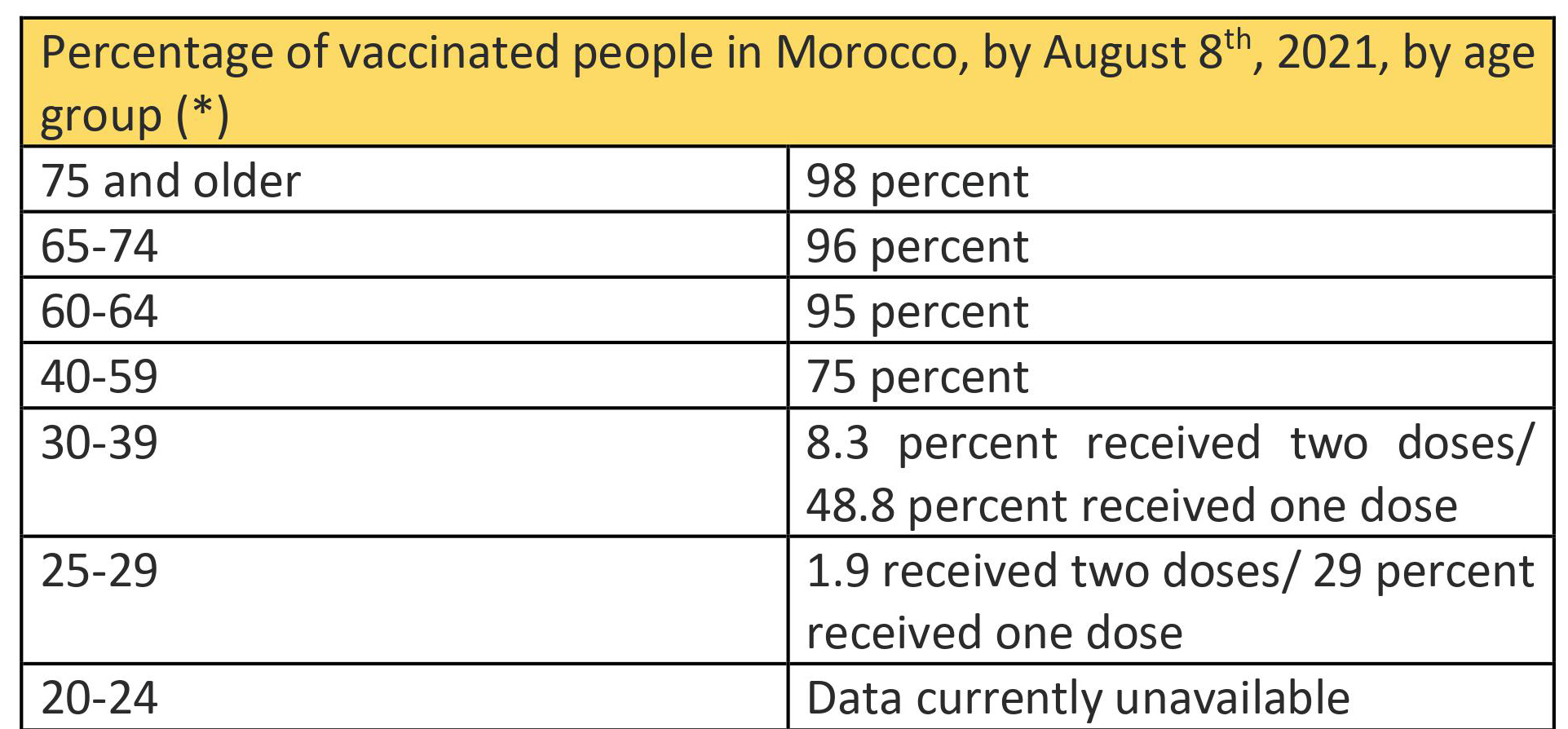

To administer its available vaccine doses, Morocco has adopted an age-group approach and a system of professional categorisation. Initially, 40-year old healthcare workers and older were targeted, followed by public and army officials, as well as the elderly (75 years and older). Then, age groups of 65-74, 60-64, 40-59, 40-39, and, finally, 25-29-year olds were contacted, in that order. As of August 7th, age groups have been extended to include 20-year olds and older.

Vaccination in Morocco is free and administered all throughout the country, without exception. In principle, in order to control the viral outbreak, vaccine priority is given to those cities and provinces more contaminated than others. However, no official data shows that such a standard has been respected during the past months. Initially, the campaign relied on AstraZeneca and Sinopharm vaccines, as they are less costly in terms of both substance and storage conditions (requiring normal levels of refrigeration). Imported doses were stored in the headquarters of the Independent Refrigeration Agency in Casablanca, considered to be the national vaccine bank. There, they awaited redistribution to the rest of Morocco’s cities and provinces.

During vaccination: Fears of AstraZeneca

Throughout January and February 2021, vaccination maintained its pace, but slowed down in March, due to the delayed arrival of AstraZeneca’s vaccine – manufactured in Serum in India. At the beginning of the vaccination campaign, Morocco mainly relied on AstraZeneca more than it did on Sinopharm [1], which had smaller supplies during the first three months of the vaccination campaign. Although Morocco had approved the administration of additional vaccines, like the Russian Sputnik V and the American Janssen, it received none of those during that period.

The delay, and slow-paced vaccine shipments, from the Serum Institute in India to both Morocco and the rest of the world could be explained by the explosion of the outbreak witnessed in India. The institute was thus forced to respond to Indian demand and suspend its vaccine exports to Morocco and the rest of importing countries.

Suspended exports by the Indian vaccine manufacturer were not the only reason, however, behind a decelerated vaccination pace in the country. Rather, unconfirmed news of AstraZeneca-induced “deaths” spread and drove some Moroccans to temporarily refrain from vaccination. The issue stirred up a storm of popular fears, while controversies among scientific circles grew as Western countries decided to either suspend or completely halt using this vaccine – due to an increased death toll and blood clotting cases following vaccination. In this context, Aziz Ghali came out once more to announce to public opinion that the AstraZeneca vaccine had caused some deaths among vaccinated people in Morocco: three in Casablanca and one in El Jadida city. He accused the Ministry of Health of “hushing down these cases” and other such cases of people suffering post-vaccination side effects.

In early July 2021, the Delta variant snuck into Morocco, at a time the country had high hopes in the recently eased measures, following a difficult month of tightened control during Ramadan. Such factors, however, resulted in an increased number of infections by the day, peaking after Eid al-Adha, which reached more than 12 thousand cases on August 5th.

The Moroccan Ministry of Health denied Ghali’s words and others’ that exposed the “hazards” of this vaccine; they affirmed that no deaths were recorded among individuals vaccinated with AstraZeneca, due to post-vaccine side effects”. It also mentioned that members of the scientific committee stated that “The benefits of the AstraZeneca vaccine outweigh its risks, and no direct link could be traced between such side effects and its use”.

Delta sneaks in: Vaccination extended and restrictions reintroduced

In early July 2021, the Delta variant snuck into Moroccan territories, at a time the country had high hopes in the recently eased measures, following a difficult month of tightened control during the month of Ramadan.

Eased measures included reopening public baths and beaches, allowing weddings with a restricted number of invitees, and reducing curfew time, from 11pm to 4:30am. Most importantly, borders were reopened to tourists and travel facilitated for diasporic Moroccans – by lowering both flight prices and sea travel fares.

Such factors, however, resulted in an increased number of infections by the day, peaking after Eid al-Adha, which reached more than 12 thousand cases on August 5th. Authorities once again mobilized and approved partial restrictions, starting at the end of July 2021. They extended night-time curfew, which would start at 9pm, and restricted transportation, by stipulating an intercity permit, which is a bureaucratic procedure made in Ministry of Interior departments. They also banned travel to three cities, which had the highest infection numbers and death tolls: Casablanca, Marrakech, and Agadir.

Such a reality forced health authorities into a state of vigilance and urged them to quickly contain pandemic – especially since the Delta variant had also been circulating among younger generations. The available solution was to increase the number of vaccination centres and healthcare personnel; they called in retired nurses and recent graduates and interns, extended weekday work hours until 8pm, broadened the age groups eligible for the vaccine to include people in their 20s, and discarded residence requirements, which enabled individuals to receive the vaccine anywhere in Morocco, regardless of their resident address. Such sanitary measures coincided with the receipt of 4 million Sinopharm doses, between July 27th and August 8th, 2021.

While important, such a decision triggered a state of suffocating traffic, chaos, and randomness in most vaccination centres. Medical procedures were thus up for critique, as prefixed appointments were no longer required, as was the condition of proximity to a vaccination centre. Healthcare centres designated for vaccination thus sunk into an unprecedented state of overcrowding.

These “preventive” decisions are incomprehensible to a significant swathe of popular opinion. Many Moroccans see that night travel bans do not effectively contribute to controlling the pandemic, so long as people collectively participate in spreading the coronavirus – through irresponsible and chaotic practices, like overcrowding or disrespecting preventive measures during the day.

In parallel, Morocco intensified vaccine imports to include (other than the recently imported Sinopharm) Janssen, the American vaccine, of which it received more than 300 thousand doses as a gift from the United States, and as part of the UN vaccine administration plan, COVAX. The country thus guaranteed that more than 300 thousand Moroccans would benefit from a full course of vaccination as, unlike the rest of vaccines that required two shots, the Janssen vaccine required only one shot for a full course.

Preventive measures: Between tightened and eased

Although the vaccination eligibility circle has been expanded to include more Moroccans, governmental “preventive” measures continue, even if bouncing between tightened and eased. The government justifies the continued measures in saying that receiving the two Covid-19 vaccine shots “does not prevent carrying or transmitting the virus” and that “herd immunity requires that more than two thirds of the population at least should be vaccinated. Preventive measures must therefore continue to apply for both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals”.

Although the government approved a resolution stating that vaccine passport holders were now exempt from the intercity travel ban, travellers were left helpless. Some security men sometimes floundered or showed “moodiness” in their treatment, demanding that travellers held, along with the vaccine passport, intercity and interprovincial travel permits.

Despite the continued vaccination campaign, which targetted essential frontline groups and millions of individuals from the entire age spectrum, such a “preventive” measure (as termed by the government) and many others have yet to be permanently repealed, or even permanently eased. Even if such a number were insufficient to achieve full herd immunity (more than 10 million individuals vaccinated by August 7th), these “preventive” decisions are incomprehensible to a significant swathe of popular opinion. Many Moroccans see that night travel bans do not effectively contribute to controlling the pandemic, so long as people collectively participate in spreading the coronavirus – through irresponsible and arbitrary practices, like overcrowding or disrespecting preventive measures during the day. Other questions equally come to mind: “Why are certain places closed and others opened? Like shutting down public baths and beaches during winter, as opposed to opening popular markets and overlooking overcrowding in buses, for instance… This is futile and shows double standards”. Such were the words of people opposed to preventive and tightened measures.

Doubts about the Chinese vaccine, Sinopharm, snuck in. Many branded it as a “mysterious” medicine, hailing from an Asian country, whose full vaccine details were yet to be revealed. Generally, Moroccans’ comments showed concern; they considered the vaccine to be a tool to “control” and “conspire against” them –by “plugging” or “planting an e-chip in their bodies”, one way or another– or even to cause some genetic mutations, instigated by “major Powers” and their giant institutes.

When adopting such “preventive measures”, the government, along with the scientific committee (acting as its advisory authority), justifies the maintained months-long travel ban by confirming that it has contributed to reducing the number of infections, especially during the past month of Ramadan, known for increased night-time social gatherings. The government also sees that the partial lockdown and night-time curfew are kinder to the national economy than a full-blown lockdown. Adopting a full-blown lockdown would be semi-suicidal and would push the country into collapse. Here, the government tries to have it both ways, but its decisions have a hint of clumsiness, arbitrariness, and improvisation.

A Moroccan Sinopharm: Towards self-sufficiency in vaccines

At a time when Morocco rushes to vaccinate the biggest number of Moroccans possible in order to avert the dangers of the third Covid-19 wave (the Delta variant), the country not only tries to continue vaccinating Moroccans with Sinopharm and AstraZeneca, or with the Janssen it received through the COVAX initiative, but also looks to adopt a whole variety of other vaccines, including Pfizer, with whom Morocco has managed to conclude a deal. According to local press sources, 1.8 million doses are expected to arrive in Morocco, but no set date has been fixed yet. The Russian vaccine, Sputnik V, will also be authorised in Morocco, to be administered to nearly 20 percent of Moroccans, according to a statement by its Russian sales representative in Morocco.

It seems that the Chinese Sinopharm shall be most prevalent over the current [2] and future vaccination campaigns in Morocco. The deal concluded between Morocco and Sinopharm Group could attest to that, with 500 million USD invested in the deal. The goal is to locally manufacture the vaccine in an attempt to enable self-reliance – by producing, bottling, and packaging 5 million vaccine doses a month, to be exported to Maghrebi and African countries.

In January 2021, after media platforms broadcast King Mohammed’s VI first vaccine shot, such concerns and doubts gradually subsided among the general Moroccan public. Some of the doubtful and fearful thus changed their mind; to them, so long as the country’s ruler has so confidently taken the vaccine, such a step should not be shrouded with so much doubt.

Practically, hi-tech production units will be built in Mohammed VI Tangier Tech City. Three agreements have been signed thus far: The first is a Covid-19 vaccine Memorandum of Cooperation between the Moroccan state and the China National Pharmaceutical Group (Sinopharm). The second is a Memorandum of Understanding between the Moroccan state and Recipharm company, on manufacturing capacities and capabilities. The third agreement is a contract that guarantees putting the sterilised packaging facilities at Sothema (the Moroccan pharmaceutical company) at the service of the Moroccan state: in an aim to co-manufacture the Sinopharm Covid-19 vaccine

In conclusion

During the past seven months, the vaccination campaign in Morocco has been adequately smooth and well organised. Exceptions to the rule have been a few technical issues caused by the mounting pressure on vaccination centres, as more groups became eligible and turned out for vaccination. Morocco’s big challenge is still to weather this sanitary crisis in a flexible manner and with the least damage possible. It must also manage to avoid the mistakes and blunders that marred some of its “preventive” measures, notwithstanding their importance and overall logic.

At large, and when compared with the countries of the region, Morocco has handled the vaccination campaign in a serious manner (ranking fourth in the Arab world and first in Africa in terms of vaccinated individuals, by August 7th). It has managed to vaccinate a third of its population (more than 30 percent by August 8th, 2021), ensured that frontline response workers and the elderly were fully immunized, and managed to obtain the rights to manufacture the Chinese vaccine in its territory. Will it also achieve herd immunity in the near future?

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 12/08/2021

[1] Since the beginning of the vaccination campaign and until February 27th, 2021, Morocco received 7 million AstraZeneca doses, as opposed to 1.5 million Sinopharm doses, received since the beginning of the campaign and until March 8th, 2021.

[2] Since the beginning of the vaccination campaign and until August 8th, 2021, Morocco has received 22.5 million Sinopharm vaccine doses – the largest batch when compared with the number of AstraZeneca doses received, estimated to be around 8 million doses.