This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

During the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, Tunisian crowds caught the world’s attention with their clamour – both inside and outside the playing field – through the different ways they showed support for their national team, in addition to their repeated gestures in solidarity with the Palestinian cause. Through folk songs, banners, flags, and even by barging into the field to raise the Palestinian flag, Tunisian football fans proved their longstanding passion for the sport. To them, football is more than just a game. They “breathe” football.

The sport was introduced to Tunisia in the late 19th century by the French colonizers. It quickly became one of the “spoils of war” that the locals appropriated. Over the course of a century, a football love story unfolded. It started with political activists, intellectual elites, and “dignitaries”, and was later embraced by younger generations, various popular factions, and the working class. The story reached its peak at the beginning of the third millennium, as the “ultras” entered the scene, with a passion that has always existed at the touchline with power and politics.

A brief political and economic background

Until the end of World War I, football remained exclusive to French and European colonizers. When Tunisians tried to form their own teams, colonial authorities stood in the way of their efforts, and when they finally licensed the first Tunisian team, Espérance Sportive de Tunis (Sporting Hope of Tunis), in 1919, the colonial authorities were keen on imposing a French manager. However, they later backed down, and allowed Tunisians to form and run their own sports teams. Notably, the teams that emerged in the period between the two world wars emphasized their national identity through their names, like the Sportive Hope of Tunis, the Islamic Club (now the Club Africain), the Tunisian Club (now Sfax Club). The first generation of Tunisian team founders belonged to the relatively educated and well-off classes. These are the same circles that played an important role in establishing the Constitutional Liberal Party in 1920, which later became a leading force of the national liberation struggle against French colonialism. Since the 1930s, the Constitutional Liberal Party has attempted to engage in every social facet and address the various aspects of Tunisians’ daily life, not excluding the importance of football in the country.

The interplay between politics and sports continued into Tunisia’s independence and the Constitutional Liberal Party’s governance, headed by Habib Bourguiba. In 1961, a pivotal year in Tunisian history, where the authorities imposed a one-party system and state-controlled media, the president of the republic issued a decree to dissolve the Etoile du Sahel team after its fans clashed with the police on the football field. This was followed by angry protests in the streets objecting the referee’s bias to the rival team, the Espérance Sportive, considered by the majority of the football public in Tunisia to be the “regime’s team”. That was the initial warning the authorities made to sports teams and to those who joined the ranks of the opposition. In 1971, other protests broke out, led by the Espérance Sportive fans, to challenge the decisions of the football league. In response, the Ministry of Interior decided to suspend the team’s activities. The decision was unrevoked until the president of the republic allowed it. It was clear that the regime recognized the potential influence of football fans in mobilizing the population, and so it deployed “fan infiltrators” whose mission was to “curtail” fans, while ensuring that club managers were affiliated with the ruling regime or even the government.

During Ben Ali’s rule, the regime’s control over football sprawled, and football began to be used as tool for propaganda. Despite some “achievements”, Ben Ali’s era was harmful to football in Tunisia as corruption and regime bias towards certain teams grew rampant. It became especially so when the president’s son-in-law, Salim Chiboub, became president of the largest Tunisian club, Espérance Sportive, from 1989 to 2004, enjoying absolute power to intervene in every aspect of sports in the country.

Even when it comes to economics, Tunisian football reflects major injustices and failed economic decisions in the country, whereby wealth, economic vitality, and official concern remained channeled towards the same regions. Since the country’s independence in 1956, Tunisia has had 67 sports seasons, during which the “Big Four”, aka the teams of the four biggest and richest Tunisian cities, have garnered 60 titles: 32 for Espérance Sportive (Tunis, northeast), 11 for the Club Africain (Tunis, northeast), 9 for the Etoile du Sahel (Sousse, central east), and 8 for the Sfax club (Sfax, central east).

Until the end of WWI, football remained exclusive to French and European colonizers. When Tunisians tried to form their own teams, colonial authorities stood in their way, and when they finally licensed the first Tunisian team, Espérance Sportive de Tunis, in 1919, the colonial authorities were keen on imposing a French manager. However, they later allowed Tunisians to form and run their own sports clubs.

While some clubs are active in cities with a relatively developed and diverse sports infrastructure, most teams train and play in shameful conditions.

The big city clubs, mainly the “Big Four”, enjoy great popularity and extensive fan bases that provide financial support. The clubs also profit from participating and winning in local and continental competitions and from revenues garnered from advertisements, television contracts, and match tickets. The smaller clubs, on the other hand, mainly active in impoverished inland regions, live off of bursaries and aid from regional and central authorities and the financial support from well-off relations.

Adopting the “non-amateur” system in 1995, then the “professional” system in 2005 (1) was what debilitated most medium and small organizations, as the “Big Four” grew in dominance. Even the teams affiliated with the public sector that used to play in the Champions League until the 1990s, adding their unique touch to it, couldn’t survive capital’s control over football.

Authoritarian practices and economic injustices stirred up regional sensibilities across the country and intensified rivalries between teams in the stadium. Since the late 1990s, violence has been on the rise in playing fields, as slogans and chants became more politicized, especially with a new player in the picture: the “ultras”.

The ultras are bigger than stadiums

As the mid-1990s set in, emergent features of the ultras’ culture began to show in Tunisian stadiums. However, the official and organized appearance of the ultras in the country would only arrive with the beginning of the third millennium, rendering Tunisia a pioneer in ultras culture, both across the Arab World and Africa. The groups multiplied as the years went by, but their numbers remained relatively limited during the Ben Ali rule.

The 2011 uprising set off a new phase in the ultras’ history in Tunisia, not only in terms of the multiplying number of ultras groups, but also in terms of their culture’s reach. More than 60 Tunisian ultras groups have appeared since 2002. The biggest four teams, especially Espérance Sportive and the Club Africain, control almost half of these groups, and the rest are distributed over more than 20 teams. Some have been active for two decades, while others have only been there for a few months. Likewise, these groups differ in size and popularity, depending on the team they support, the demographic importance of the city a given club represents, as well as seniority. Some groups comprise tens or hundreds of members, while some comprise thousands.

In the following paragraphs, we’ll try to draw a comprehensive picture of Tunisia’s ultras, not only as fan base frameworks with their own structures, identities, and regulations, but also as artistic expressions and a political and social phenomenon in their own right.

1. Structures

Similar to ultras groups all over the world, Tunisian ultras do not follow any set structures. And yet, there are recurrent models, with slight differences between countries, among groups in the same country, and even among groups supporting the same team. According to researcher Mohamed Fakhreddine Louati, two dominant models exist in Tunisia. The first is perfectly top-down, where we find the Capo (“leader” in Italian) at the top, the “Nucleus” (Noyau) as the second men right below the Capo, followed by a median group called the “Staff”, then the “Sector Chiefs” who overlook the sectors or regions that house the ultras’ branches. At the very bottom of the pyramid, we find the rest of the members. Louati finds that in this model is the one most commonly adopted by ultras groups in Tunisia, especially among the most senior and popular ultras, and sees that it “depends on a hierarchal structure of organization and centralized decision-making, because it relies on the Capo to lead the group (2).”

2. Identity components

Naturally, the first identity component would be the name. Most ultras in Tunisia have given their groups English, Spanish, or Italian names, perhaps to affirm their affiliation with an international/globalised movement, as well as with South American and Italian ultras’ heritage. French names are moderately present, while Arabic names are semi-absent. Ultras seek inspiration for their group names from various sources:

- The distinctive colours of their team

- The name of their team or its hometown

- A lexicon of force, war, and courage: Fedyan, Power Marines, Gladiators, Fighters, Brigade rouge, Zapatista, Ultras Vikings, Partisans, Espérantistes, Pirates, Vandals…

- A lexicon of fraternities and gangs: the word “boys” comes up, in the sense of an organized group, in more than ten ultras groups. Sometimes it comes up in Spanish, as in the Chicos Latinos group.

- A lexicon of playing fields and fans: in reference to the positions that ultras members take in the public stadiums, often a southern or northern “curva” (curve, in Italian).

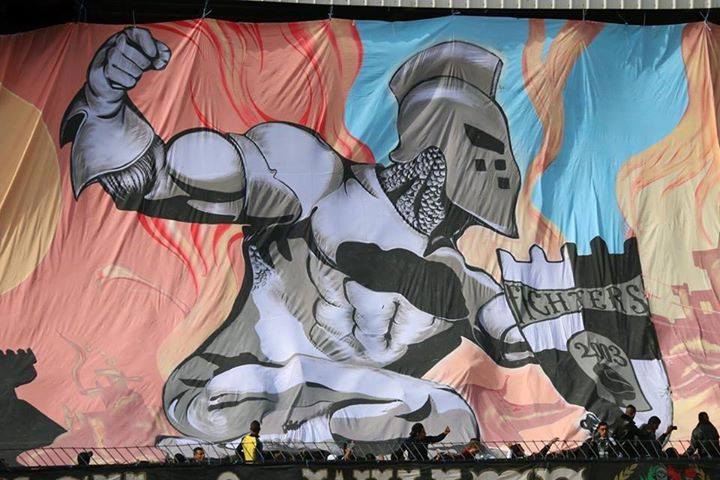

Logos are the second identity component in ultras’ identity making. It is a condensation of various elements at the same time: the group’s name and date of birth, the distinctive colours of the team it supports, and the mascot. In many logos, images of vigorous fighters from ancient or modern history appear, as well as characters inspired by global series and films. Sometimes, a mascot may be present in the stereotypical image of an ultras’ member, who covers their face with a headband and a scarf. Some groups choose a wild beast or an animal that symbolises power, like a bulldog, a lion, or an eagle, or make do with symbols, like a shield, a spear, swords, the revolution hand, or a skull.

The third, and possibly most important, element, as it is related to the birth and “death” of an ultras group, is the “bâche”. The bâche is a rectangular textile or plastic piece upon which the name of the group, its distinguishing colours, logo, and other elements that express its identity appear. An ultras group will not receive real acknowledgement unless it raises its own distinguished “bâche” for the first time in the stadium. In fact, when an ultras group seizes another group’s “bâche” and raises it or hangs it upside down in the stadium, the group that had lost its “bâche” must dissolve itself.

3. Forms of artistic expression

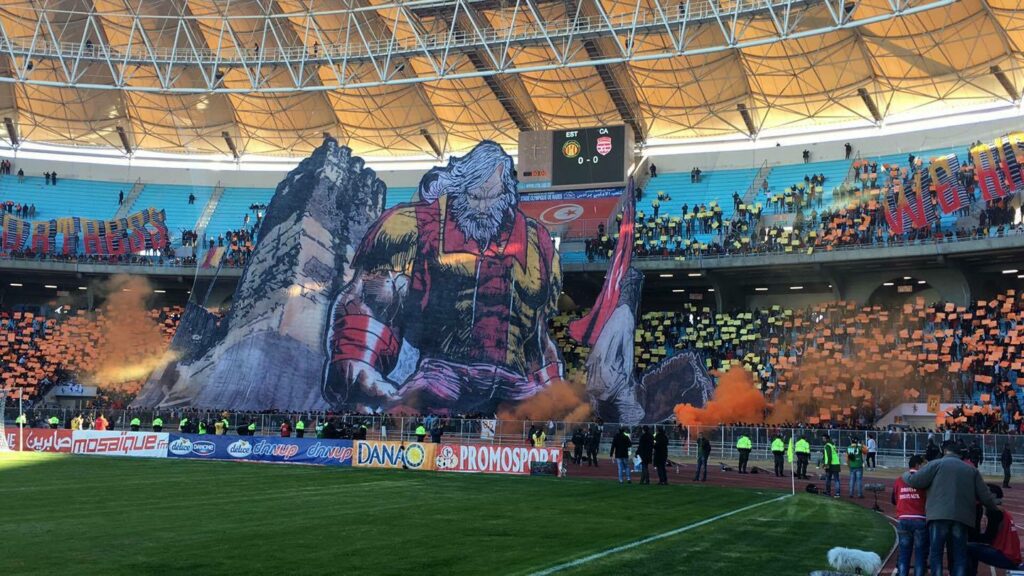

Being a sports team fanatic isn’t limited to the ultras, nor is joining a fan base and clashing with the police. What truly distinguishes ultras from other fans is the forms by which they express their identity and culture, particularly through aesthetics and creativity. Match day becomes the theatre for their spectacle, for which preparations last for days, integrating chants, drums, banners, and pyros…

The first generation of Tunisian team founders belonged to the educated and affluent classes. These are the same circles that played an important role in founding the Constitutional Liberal Party in 1920, which later became the leading force of the national liberation struggle against French colonialism.

In the stands, ultras take their positions wearing their team’s colours and symbols. They carry war drums, megaphones, and pyros, and they hang their own “bâches” over fences and walls, while raising banners with various messages. They are always ready to cheer relentlessly until the end of the match.

The preparations and efforts become even more elaborate when it comes to the “grand entrance” which the ultras call “El-Dakhla”. This is usually a captivating audio-visual spectacle, with its star element being the Tifo, a huge choreographed image that fans form by carrying parts of a the larger banner on canvas or another medium.

4. Videos of some “grand entrances”

Espérance Tunis’ entrance to the pitch during their derby match against the Club Africain

The Vandals entrance during the Club Africain vs. Monastir: (Curva Nord) Omar Laabidi

Sfax Club’s entrance during the final Tunisia Cup, 2022

The main visual elements in tifos are inspired by various sources, most prominently images of fighters and heroes, both good and evil, real and mythical. Tifos also draw inspiration from mafia and action films, anime, and famous international television series.

5. Examples of Tifos

6. Chants and songs

Chants and songs form yet another integral element of ultras’ culture, both within and beyond the playing field. While security may be able to expropriate the ultras’ signs and flags, it cannot take away their slogans and chants. These chants talk about the daily lives of ultras, their love for their team, and their sincere readiness to sacrifice what is dear to them for their beloved team. The songs try to explain the reasons young people are attracted to ultras’ culture, and the emotions they experience in the stadiums. They expose the security forces’ oppression of ultras and stress the “eternal” animosity between ultras and the police. The songs deliver strong messages to the corrupt political authorities and the rich who steal football from the poor. Of course, Palestine and other oppressed peoples of the world are not absent from the ultras epic songs.

Here are parts of the chant, “Ya Hayetna,” by the African Winners, supporters of the Club Africain. It is undisputedly the most famous chant in Tunisia, given its strong political character:

“Here is a song

About the Club Africain and its triumphant feats

About freedom and the country that has forsaken us

About the oppressed and the land that gave them up

And about revenge that remains ours to take.

The situation is this:

They steal, loot, and want to keep their immunity

Corrupt and crooked are these forces of security

How many hoods live marginalized, unemployed, in scarcity

Defeated people, sunken into drugs and alcohol.

You’ve sold us out

Looted millions and hid them abroad

And you looked away as they took it all

Let cocaine into the country and made it worse

Pushed people out of their homes into faraway lands.

A system

We hate, so merciless

We’ll never forget those who died in the truck accident

(Women farmers having to use unsafe transportation)

Or the mother who delivered her child in a cardboard box

What a pity that they die and you remain alive.

O, judge,

We’re demanding justice, tired of empty words

Everyone dies, and we accept God’s judgement

Only the Curva can cure my ailment

We fight the system with no regret.

7. Graffiti

Artistic expressions are not limited to the ultras’ presence in the stands, but go beyond the stadiums and onto the white walls of the city streets. Of these expressions, Graffiti appears to be the most prominent form of ultras’ artistic articulation. With the fall of Ben Ali and the liberation of the public sphere, the road was paved for a new era in ultras’ culture, fuelled by the flourishing street arts and freedom of expression in the country.

Tunisian football reflects major injustices and the failed economic decisions in the country, whereby wealth, economic vitality, and official concern remain channeled towards the very same regions. Since independence (1956), Tunisia has had 67 sports seasons. The “Big Four” clubs have garnered 60 titles!

Authoritarian practices and economic injustices stirred up regional sensibilities across the country and intensified rivalries between teams in the stadium. Since the late 1990s, violence has been on the rise in playing fields, as slogans and chants became more politicized, especially when the “ultras” came into the picture.

Ultras were given the chance to create colourful graffiti art and grand murals, ushering in a new era of creative rivalry among the various groups.

Examples of graffiti works

No justice, no peace!

A quarter of a century ago, the ultras stormed the Tunisian socio-political scene, transcending the boundaries of football fields. However, during this relatively short time span, the ultras’ journey can be understood through discerning three distinct phases.

Football in Egypt: Where People Find Solace

08-06-2023

Football in Iraq: A Game of People and Politics

02-06-2023

The first phase encompasses the final decade of Ben Ali’s rule, from 2000 to 2010. Ultra groups began to emerge during that period, the majority of which comprised the supporters of one of the “Big Four” clubs. Ultras’ presence and influence grew in the stands, but never reached the same levels observed in Europe or South America. While tolerant at first of the new phenomenon, Ben Ali’s police state iron grip imposed certain limits on the ultras. Those limits were broken for the first time, however, on April 8, 2010, when heated confrontations broke out between the Espérance supporters, including the ultras, and the security forces, where the authorities resorted to extreme violence to “control” the crowds. Prior to that “incident”, physical violence was present in the stadiums, but would often take place among the competing teams’ supporters. Violence towards the regime, on the other hand, was predominantly verbal and allusive.

Ben Ali’s downfall in January 2011 signified a rebirth for ultras’ culture in Tunisia. The numbers of ultras’ members surged as fans of teams big and small in the premier league and beyond began to found their own groups. This widespread phenomenon unfolded despite the governments’ and security forces’ attempts to restrict ultras and football crowds in general. In between December 2010 and November 2012, the public was prohibited from attending football games, citing the “volatile security situation” as an excuse. Then crowds over the age of 20 (later revised to over 18) were gradually allowed back into the stands. Curbing the ultras’ participation in matches intensified the resentment they had for the regime, but also consolidated their presence in the street as an alternative to the stadium. Hence, they expanded their presence in the streets through artistic expression and mobilizing in social movements.

The third phase, which is still ongoing, began on March 31, 2018. On that day, a game took place between the Club Africain and the Médenine Olympic at Radès Stadium, which concluded with police violence and a horrific oppression of fans. Police brutality extended beyond the stands, as they pursued and targeted individuals outside the stadium. Omar Laabidi was a member of the Club Africain ultras’ who fell into the hands of security forces. The young man was thrown by the security officers into the waters of the Oued Miliane valley. According to eyewitnesses, Omar tragically pleaded for help, but the security forces taunted him with the words “Learn to swim!” Eventually, the water swept Omar away, and he drowned at the young age of 19.

The 2011 uprising ushered in a new era in the ultras’ history in Tunisia, not only in terms of the multiplying number of groups, but also in terms of their culture’s reach. More than 60 Tunisian ultras groups have emerged since 2002, and the biggest four clubs control almost half of these groups.

This coldblooded crime infuriated public opinion beyond the ultras’ circles. The hashtag #learn_to_swim spread throughout social media. Thanks to public pressure from the football crowds and the mobilization among civil society organizations and a large number of lawyers, the case was submitted to the courts. After more than four years of painstaking efforts, the court of trials charged 12 policemen involved in the case with “involuntary manslaughter”.

Omar’s death further marred the atmosphere in the football stadiums, and violent clashes became more frequent, to a point where in 2019, the authorities decided to prevent football crowds from sharing the same stands the ultras usually occupy in the stands. This raised the ultras’ youth vengefulness against security forces, further fuelling the strife.

***

Football is more than a game. It has always exposed the political power’s endeavours to control, survey, subjugate, and whitewash. In a way, it’s a mirror that reflects the country’s illnesses (dictatorship, classism, regionalism, and corruption) as well as its prettier face: its passionate and, sometimes, fiercely angry fans, with their resistance and creativity. Today, Tunisian authorities face one of the most confrontational generations of football fans in the history of the country. What the Ultras demand is exactly what the majority of Tunisians have been demanding; their right to dignity and joy.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 15/05/2023

1- Before 1995, football in Tunisia was an amateur sport. That means that a player could be a member of one big team, play on Sunday, and then work the rest of the week in different vocations. This used to also apply to the technical and administrative cadres, whose number was limited. Teams’ incomes were limited and depended on public funding and donations. In the early 1990s, a decision was made to adopt the professional system, based on legal contracts and regulations regarding duties, rights, salaries, and grants, requiring that those contracted to practice football must be completely devoted to it. The system also offers certain infrastructures along with certain privileges, like a share in television broadcasting rights and stadium tickets. Since most Tunisian teams were not qualified for such a quick transformation, the “non-amateur system” was adopted as a form of a transitional period. In other words, it was a professional system with watered-down conditions.

2- Mohamed Fakhreddine Louati: The Culture of Ultra Groups in Tunisia, p. 16. A study published by the National Youth Observatory, Tunis, 2021.