This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

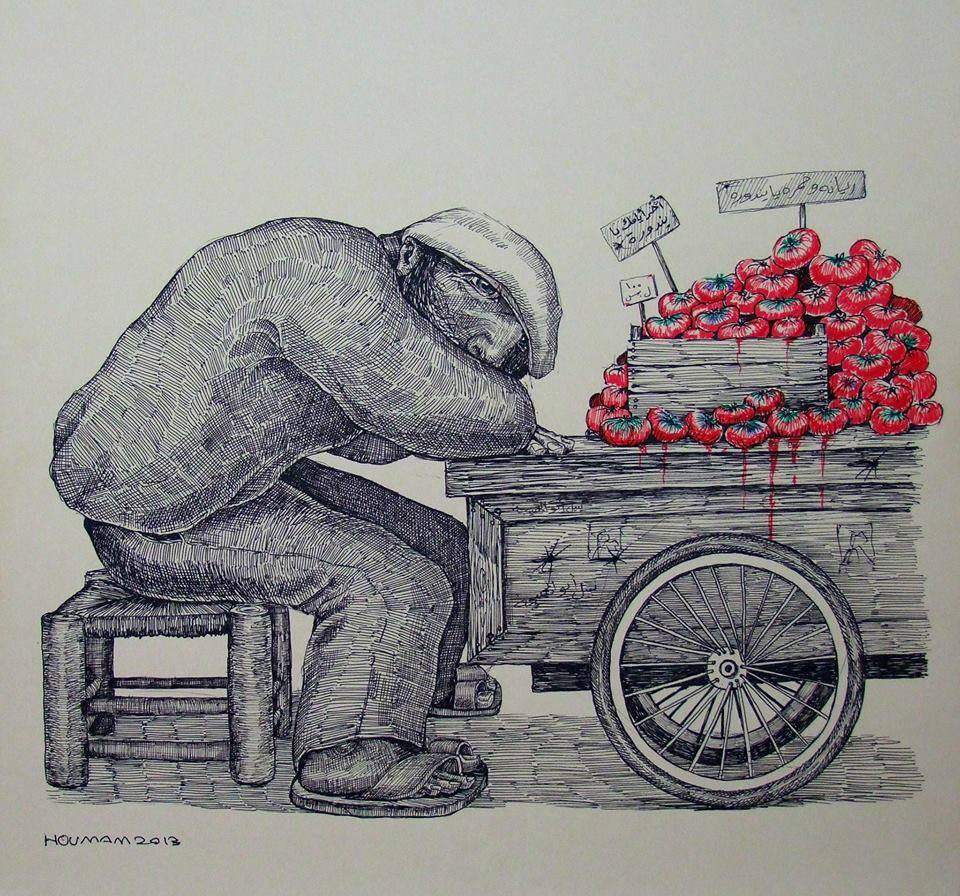

"Ba Amahmed" has been a salesman for more than three decades. After years of dodging the local authorities, he has finally managed to seize a spot on the pavement to display his goods. His merchandize varies in kind and quantity based on the market’s needs in different seasons. During the summer, he sells wild figs and watermelons. In the winter, he displays ‘made-in-China’ winter clothes, and, in other seasons, he sells sweets and holiday-related items. When these products don’t sell well, his pavement kiosk presents smuggled or second-hand goods.

The government classifies this kind of work as part of the "parallel economy" or the "informal economy". This means that the work of “Ba Amahmed” is illegal in the government’s eyes, making him an enemy of the small dealers and contractors. He does not pay income taxes, water or electricity bills or tax receivables for the local authorities. Those who, like “Ba Amahmed” are dependent on these sorts of activities are multiplying every year.

Alternative Economy

According to statistics, the net profit of Morocco's parallel economy represents about 41 billion dollars. The number is so huge that it could be compared to the income of a poor country resisting debt. But what about Morocco’s debt itself? It all started in the 1980s when the government announced that the country was in a 12-billion-dollar debt, with its economy dangerously waiting “in the emergency room”. Borrowing from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was inevitable. A process of "structural reform" proceeded as the government resorted to the privatization of several public sectors and removed governmental subsidies on basic food products. These were attempts to reduce the burden of the debt and pay the due interests. In that difficult phase and with the deterioration of an “ill” formal economy, the activities of the shadow economy grew fervently. This economy which became bigger and stronger within the social and economic conditions of a chaotic environment, was able to disengage from the government’s authority, restrictions and demands.

For the government, the cure is the disease. Despite the fact that the parallel economy deprives the state’s treasury of hundreds of millions of dollars, the government recognizes that it also contributes to the resuscitation of the national economy in several ways. The parallel economy annually invests a capital of about 336 million dollars. Its activities grew by 3.2 percent overall, almost 1.1 percent of the fixed national capital, since 2007.

More than 2.4 million Moroccans engage in ‘black practices’ (or work in the informal economy), more than half of them work in informal trade, 24.5 percent are in the service sector, and 16.1 percent are employed in the industrial sector. The government finds it difficult to integrate these workers into the formal economy. Since it is incapable of solving the problem, the government simply ignores the presence of these workers. It relies on the unregulated economy, in an implicit way, to relieve it of the burdens of making new job opportunities available, developing services and creating a comprehensive and transparent economy.

Dry Spells

The unregulated economy in Morocco was never coincidental. It emerged from the midst of many crises. By the end of the 1970s and in the beginning of the 1980s, the economy, which depended heavily on agriculture, began its fast spiraling descent after the years of drought. The parallel economy began to formulate from that moment on.

The “stubborn” sky gravely harmed the villages’ farming and agricultural products. For every one year of rain, there would be 3 years of drought, and the farmers prayed for a rain that did not come. The dry brown earth was the only thing that remained, desolate and waiting to be salvaged and revived. Many farmers were consequently forced to sell their land and therefore decided to pack their bags and head to the city in search of income and sustenance.

Migration to the cities increased the urbanization rate by over 50 percent during the 1990s. The villagers’ migration was motivated by the drought, poverty and the marginalization of the peripheral areas. They left behind their land and everything that was important to them. The question was how they would survive in Casablanca, Rabat, Marrakech, Tangier, Agadir, Fez or Oujda, the cities of attraction that had witnessed the constant influx of rural migrants until the third millennium. The migrant villagers, like Ba Amahmed, usually choose to work in manual labor or seasonal jobs as construction workers, washers, street salesmen. etc. The work they do is most likely unregulated and classified outside the formal economy.

A Distorted Morphology

This system produces structurally distorted cities. All major cities are witnessing the emergence of slums, “backyards” or “black margins”. For example, most economic activities, including “shadow activities” of trade, import and export, and other illicit transactions, are concentrated in Casablanca. Hence, the city demographically explodes year after year as it continues to attract expatriate villagers fleeing the geographies of poverty and marginalization.

Ba Amahmed, like many other who share his circumstances, is forced to settle in the outskirts of Casablanca in the shantytown and to live a “tin-box” house in neighborhoods not far from the center, such as the “Carrière centrale” (Kariane) or the “Mohammedi Quarter”, or in far ends of the outskirts in “Sidi Moumen". As the Moroccans often say, the city is trying to get rid of its “snot”! However, those attempts fail as the many manifestations of the shadow economy still produce slums and shantytowns that poorly frame the contradicting city center’s skyscrapers!

Peddlers make the most of the quiet nighttime which allows them to avoid the authorities while they build simple cabin shops of four walls and a zinc roof. They try to catch up with the common lifestyles they witness around them, so they install giant satellite dishes on top of their metallic roofs. This is their way of trying to improve their social conditions and escape their gloomy reality. In their narrow alleys, basic services like transportation, sanitation and potable water are nonexistent. The state’s go-to response to the inhabitants’ objections is "you do not pay taxes, this is how you deserve to live". Nevertheless, the residents still try to seek alternatives to governmental services in their ongoing struggle for survival. The solidarity among them, in varying degrees, keeps them going. For example, if one needed electricity, a neighbor would offer to share a cable and split the expenses of the electricity bill, and the same happens with water or transportation.

People who partake in the parallel economy and its activities, like “Ba Amahmed”, contribute to the “ruralization” of cities. Most of the migrants do not have an elementary school education (according to a study by the Planning Commission, more than a third of them are illiterate, 33.6 percent did not go beyond primary education, 28.4 percent had a middle school education, while only 3.3 percent had access to higher education). They still adhere to the traditional lifestyle of the village, such as practicing poultry farming and herding small flocks of sheep and sometimes they rely on donkey-driven carts as a means of transportation or for shopping.

A Reservoir of Election Votes

Some street vendors cheer for their candidate in the slum’s streets “Who did we gather for?... Our only candidate X!", and so the election season begins! Every five or six years, life improves a little for those who live in the slums, but the improvement is only temporary as donations, gifts and blue paper notes are distributed to the women and men. Election season also brings promises, rosy dreams and projects about employment and a promised special market for street vendors where they could enhance their financial situation and living conditions. Representatives of the authority usually try to polarize the people in favor of one of the candidates. They address the citizens as “the protectors of democracy” who have the serious responsibility to participate in the democratic process. The people are thus politically exploited in the elections, not as citizens, but as numbers in the ballot box that may change the course of the political game.

For decades, Morocco's marginal slums, produced by the shadow economy, have shifted their political loyalty, from the socialist left to the pro-state administrative parties and finally to the conservative Islamic right. For politicians, the marginal areas are an opportunity for winning quick votes to reach the parliament or local municipal councils. Big speeches were made yet absolutely nothing ever changed on the ground. Citizens who lost all faith in the words of politicians further clung to their small selling carts and asphalt stands instead of the unreliable election boxes. In fact, they would only vote for those who were ready to ensure the protection of their street businesses in the face of the authorities’ abuse and harassment. Sometimes the authorities may resort to blackmail, promising the street vendors that they would overlook their activities and allow them to run smoothly in exchange for them voting for a particular state-supported candidate.

Manufacturing Violence

The slums offer no prospects of change and poor living conditions are perpetuated. These slums only exist because people like “Ba Amahmed” need to live, even if they have to make do with the bare minimum. They are the product of larger continuous processes that reproduce misery in its worst manifestations, giving way for the emergence of other violent social phenomena.

Those who do manual labor or street jobs in the parallel economy live in poverty with their families. The young sons usually grow up speaking the language of the streets, amid its morals and uncontrolled phenomena. “Violence makes the loudest statement” in the streets of the city where the law of the jungle reigns. The vast majority of the slums’ youth is forced to work in a seasonal economic activity that is unregulated and unstable in terms of income and sustainability. Unemployment is disguised as seasonal employment and temporary little jobs that most of the young people are forced to undertake. Although some of them hold university or vocational degrees, they are unable to find relevant jobs, which inevitably generates frustration, despair and anger. Physical violence is hence generated within their homes, neighborhoods and communities as a symbolic retaliation for their miserable circumstances.

An exemplary manifestation of the described situation is the “Sidi Moumen” neighborhood in Casablanca, a marginal neighborhood born out of the policies of impoverishment. Sidi Moumen’s population exceeds 250 thousand people, more than 80 percent of whom migrated from villages. The neighborhood, once a shantytown, turned into a concrete jungle of buildings and collective housing structures which were part of a state-implemented project since the beginning of the millennium. The project aimed to eliminate the tin shacks from the peripheries of the major cities, yet the poor neighborhoods manufactured a generation of young violent people who practiced exhibitionist violence to show “manliness”, vehemence or rebellion, and to protest the failure of societal institutions to contain them as legitimate components. In some cases, the violence reflects a desire for retaliation and suicide, like the involvement in extremist religious groups. Perhaps the most striking evidence of this occurred on 16 May 2003, when young people (including 12 suicide bombers from the Sidi Moumen neighborhood) blew themselves up in various locations in Casablanca. After the attack, it was said that the neighborhood was a “factory” that produced a frustrated suicidal youth. The authorities were quick to implement some partial localized solutions, like building nearby playgrounds, cultural and recreational spaces for young people. Despite these efforts, the neighborhood still produces suicide bombers who join fundamentalist groups outside the country and in areas of conflict such as Iraq, Syria and Libya.

According to the figures released by the Ministry of Interior in May 2017, the number of Moroccan fighters who joined extremist organizations in the Middle East is estimated at more than 1,699 fighters, 929 of those are fighting with ISIS. According to the figures, 596 Moroccan fighters died in various areas, while 213 returned to Morocco.

The youth of this slum and others are victims of political, social, cultural and economic systems that are dysfunctional and degraded. These areas have become incubators for the parallel economy. They fuel unregulated activities that continue to make sizable profits, giving substantial weight and importance to the informal sector in the Moroccan economy.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 17/04/2018