This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

No one passed! The phrase sums up the results of the entrance exams for the Master of International Studies at Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University in Fez for the current academic year, 2023. It also reflects the broader state of education in Morocco. It has appeared on multiple occasions on the results board, as several universities have formally used it on their list of entrance examination results, especially at the master's level.

While various factors may contribute to these exam results, it is clear that the caliber of candidates for these exams is lower than usual, particularly in non-scientific fields. These disciplines tend to attract students with average or weaker academic performance, and as a result, they have gained a negative reputation due to the adoption of low admission standards that fail to filter out low-achieving students. Amidst alarming figures in international rankings and other statistics that elicit pride in the number of students who have demonstrated high-level individual performances, official and international data paint a bleak picture of education in Morocco.

Contrasting images

One can easily get perplexed when reading indexes and data on education in Morocco in the last two decades. An obvious gap appears between the observed quality of schools and education and the country's low ranking in global education statistics on the one hand, and the notable individual and collective achievements of some Moroccan students in events such as the International Mathematical Olympiad and in admissions to French institutions of higher education. In these educational institutions, students are mandated to successfully complete the rigorous and highly competitive preparatory programs to qualify for entrance exams, where they compete with students from France and other Francophone educational systems.

Morocco: A Kingdom of Rent

18-04-2022

In 2021, Morocco was ranked ninth in the Arab world for education up to the baccalaureate, and 101st globally out of 140 countries included in the Davos Index for the quality of education[1]. While the wealthy Gulf countries led the list for education quality at the Arab level, other non-oil countries achieved significantly higher scores than Morocco, despite having weaker economies, such as Lebanon, Tunisia, and Jordan.

Minimum education

Based on the 2021 findings of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), only 41% of Moroccan fourth-grade primary students have achieved proficiency in reading, out of a total of 3.8 million boys and girls at the primary level. PIRLS, a continuous international assessment initiative focused on evaluating students’ reading proficiency during their fourth year of schooling, has established in its 2021 report that Morocco holds the second-to-last position among 57 participating countries.

Conducted every five years, PIRLS reports that Morocco has shown improvement compared to the previous assessment. Despite trailing behind Egypt and Jordan in tests with a representative sample of 7,000 students, the percentage of students achieving minimum reading proficiency increased from 36% in 2016 to 41% in 2021. The study results reaffirmed the ongoing superiority of females over their male counterparts, with a margin of 34 points[2].

The country has around ten million students, with 8.8 million attending public education institutions and 1.2 million in private education institutions for the 2022/2023 academic year. Additionally, 3.5 million students reside in villages.

The total number of public education students is divided by educational levels, with 3.85 million at primary schools, 1.8 million at preparatory schools, and 1.5 million at secondary schools. The education system in Morocco consists of two parts, each including three stages.

The first part, the pre-university stage, encompasses basic education in three stages: 6-year primary schools, 3-year preparatory schools, and 3-year high schools. In higher education, most Moroccan universities follow the French model: three years for a bachelor’s degree, two years for a master’s degree, and a minimum of three years and a maximum of six years for a doctoral degree.

Based on the 2021 findings of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, Morocco holds the second-to-last position among 57 participating countries.

There are two types of higher education institutions in Morocco. One type is called “limited recruitment schools”, which are selective colleges whose admission requires high grades and passing admission exams and processes. These colleges offer programs in engineering, medicine, commerce, management, and others, typically requiring at least five years of study. The other type of institutions comprises technical vocational training institutes, which require two years of post-baccalaureate study, whereby upon graduation, a student is given the title of "specialized technician". Despite the legal mandate for education in Morocco until the age of 15, a significant number of children, both boys and girls, do not receive adequate schooling. Unfortunately, the enforcement of this law is inconsistent.

Feminization of education

Upon comparing educational indicators between girls and boys, we observe a notable disparity favoring girls in academic performance and higher education enrollment. This is despite their disadvantage in educational opportunities during childhood. For example, recent data from 2023 reveals a significant imbalance, with 200,000 fewer girls than boys in primary and preparatory schools, although their numbers become equal at the secondary level.

Out of the total 3.8 million primary school students, 1.8 million are girls. There are 1.8 million students in the preparatory stage, including one million boys. There are 1.05 million students in secondary schools, half of whom are girls[3].

Moroccan Women: Protected by Law and Oppressed by Reality

21-01-2022

Tangier’s Women of Cloth

28-08-2022

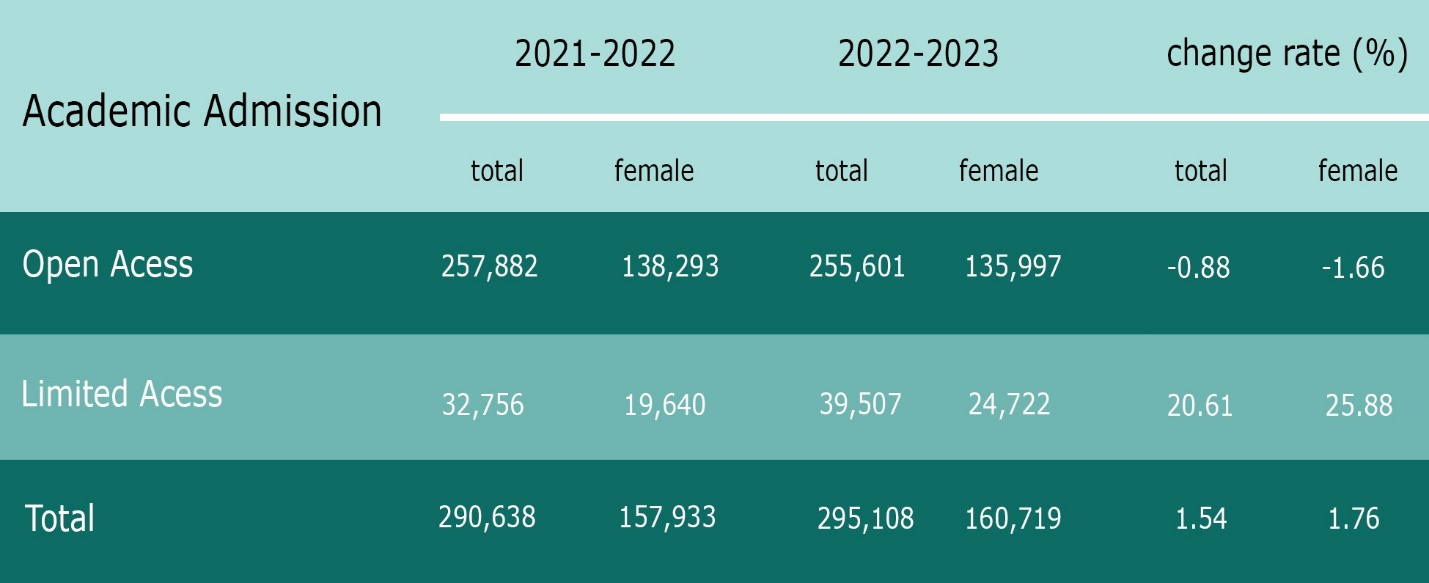

Universities prominently showcase gender differences, with female students making up over 54% of the total student population, which exceeds one million students, as per 2023 statistics. In regular colleges, the percentage of female students has reached 53% of the total number of students. However, their presence is even more pronounced in selective and high-level colleges, with over 62% female enrollment rate. This situation can be attributed to their significant representation among top-performing baccalaureate students, with girls making up 70% to 80% of all top-performers nationwide.

Overall, the baccalaureate success rates also indicate a higher percentage of female students. In 2023, 142,000 girls out of 245,000 in public and private education passed, compared to 103,000 boys. It is increasingly common for the roster of students accepted into master’s programs to predominantly feature female names, with only a minority of male names. This pattern is also evident in professional examinations.

The correlation between family social status and the proportion of female students in educational institutions is significant. Notably, in the private education sector, which accommodated 1.2 million students during the 2022/2023 academic year, there exists a balanced representation of boys and girls from middle-income households, with the percentage of female students reaching parity. This stands in stark contrast to the situation in rural areas. While there has been substantial progress in the enrollment of girls, accounting for 48% of the total 3.5 million students in the current academic year, 2023 (a marked improvement compared to two decades ago), a noticeable discrepancy emerges as they progress through the educational system. The proportion of female students diminishes at higher education levels due to various factors, including early marriage and the challenges associated with accessing distant schools in rural areas lacking middle or secondary educational facilities.

Source: Ministry of Education report on the 2022/2023 academic year outcomes.

Delays and drop outs

In key education statistics for the 2022/2023 academic year, the Ministry of National Education, Preschool and Sports in Morocco has noted progress in advancing preschool education. This area was previously a significant challenge in public education due to late enrollments, resulting in difficulties in courses requiring reading and writing proficiency. These challenges are commonly experienced by children aged three to six in preschool education. However, this progress has not yet led to overall improvements for Moroccan students entering primary school at six.

Morocco has around 10 million students, with 8.8 million attending government education and 1.2 million in private education for the 2022/2023 academic year. Additionally, 3.5 million students reside in villages. Although education is legally mandatory in Morocco up to age 15, many boys and girls do not receive adequate schooling, and this law is not consistently enforced.

Gender differences are clear in universities, with female students making up over 54% of the total student population, which exceeds one million students, as per 2023 statistics. In regular colleges, the percentage of female students has reached 53%. However, their presence is even more pronounced in selective and high-level colleges, with over 62% female enrollment rate.

In official school dropout rate indicators, an unexplained inconsistency exists between data reflecting a steady national dropout rate and figures suggesting a countrywide escalation to 5.3%, reaching 5.9% in rural regions. Over 300,000 students discontinue their education annually across all educational tiers. The dropout rate is 6% for male students and 4% for female students. Notably, a significant portion of dropouts are expelled due to recurrent academic underachievement, explaining the higher rate among boys compared to girls.

From the social gap to the educational gap

The educational gap is widening between those attending public schools and the approximately 13% of students nationwide who opt for private schools, which offer a range of low to high quality education. More middle-income families are turning to private education to address the shortcomings of public education, adding to their financial burden. This trend has led to a rise in private schools, reaching around 7,000 institutions by the 2023 school year.

Official authorities have confirmed that private educational institutions are subject to territorial distribution, allowing them to be regulated in a manner similar to public educational institutions[4]. However, the efficiency levels of these schools vary greatly, not to mention their strong focus on generating significant financial profit. Working conditions for private education teachers are inferior to those of their counterparts in public education. They are classified as "workers" and are subject to the minimum wage as stipulated in the Labor Code. Despite the law specifying a minimum wage of approximately $250, many of these schools advertise teaching positions with a salary of $170, barely enough to cover rent.

The qualifications for teachers in many private schools do not go beyond a baccalaureate degree for primary education and a bachelor's degree for secondary education, without any specialized education qualifications. Often, private schools prioritize financial gain to the detriment of the standard of education for students. However, the situation is different in highly reputable and top-tier schools, where exceptional instructional conditions are provided, including specialized training and expertise.

In official school dropout rate indicators, an unexplained inconsistency exists between data reflecting a steady national dropout rate and figures suggesting a countrywide escalation to 5.3%, reaching 5.9% in rural regions. Over 300,000 students discontinue their education annually across all educational tiers.

Private tutoring has become a significant issue within the educational system, placing a financial burden on parents. This phenomenon highlights the deficiencies of traditional schooling and its pedagogical approach, characterized by an overemphasis on quantitative measures and a lack of tangible benefits. Many tutors working in these supplementary education centers are primarily driven by financial incentives and often come from public schools that fail to provide adequate education. Despite their limited expertise, these tutors offer false promises to parents seeking additional support for their children. Furthermore, these tutoring institutions lack the structured framework found in traditional schools, ultimately exacerbating the existing educational challenges. Nonetheless, the demand for private tutoring continues to rise, with exorbitant fees for individual sessions becoming increasingly common, particularly during exam preparation periods.

Some private tutors charge $60 or more for a single lesson with one student, lasting no more than two hours. For group lessons, the cost may be around $20 per student in a class of thirty, resulting in $600 for the teacher. However, weekly classes are also available for a monthly fee of under $10, but the quality of these tutorial centers' services is often subpar.

Private schools with private interests

In 2020, the Competition Council, a government body, reported disparities in private education services. It noted that private education has become more accessible to investors, allowing them to determine curricula based on the school's environment and the quality of services. As a result, the number of private schools doubled from about 3,000 in the 2010-2011 academic year to 7,000, surpassing the growth of public sector schools, which only increased by 16% to 11,250. It is worth noting that these statistics do not include private tutoring centers and language teaching centers.

It is worth noting that private schools in the country were not initially driven by profit. They played a significant role in the national movement to confront French schools in the 1940s and 1950s. Until recently, they were referred to as "free schools" to differentiate them from foreign mission schools, which were established for the education of children from foreign communities and some affluent Moroccan families. The name also sets them apart from religious schools, such as those for Moroccan Jews who wanted to provide their children with an education based on Jewish teachings. The Israeli World Federation funded these schools and used them to keep track of their members.

After Morocco’s independence, Moroccan investors founded private schools of a non-profit nature to provide educational options for individuals who were unable to fulfill the criteria for public education, including meeting the minimum enrollment age. As public education declined and families sought alternatives, it became apparent that private schools main aim was profitability. Private schools witnessed a substantial rise in student enrollment, with a 74.5% increase since 2010, while the increase in public school enrollment did not exceed 9% during the same period. The teaching staff in these schools totaled 55,000 for the 2019-2020 academic year[5].

The profitability of private schools is currently facing some issues due to pricing and service discrepancies. Most schools that offer limited educational services and focus only on primary education programs are small and medium-sized. These types of schools are prevalent in the regions of Casablanca-Settat, Rabat-Salé-Kenitra, and Fez-Meknes, which are the primary urban centers where families place a strong emphasis on high-quality education. Private education is quite expensive, so many families prefer to enroll their children in public schools during the preparatory stage. As the private school fees increase significantly from the preparatory stage onwards, families are confident that their children have received a good education in primary school, which will prepare them well for the subsequent stages.

Private education has become more accessible to investors, allowing them to determine curricula based on the school's environment and the quality of services. As a result, the number of private schools surged from about 3,000 in the 2010-2011 academic year to 7,000, surpassing the growth of public sector schools.

As per the Competition Council, establishing private schools that operate for profit restricts access to those who can afford it, thereby limiting their services to children from middle-class and higher-income families and leading to a significant reduction in educational opportunities for students in areas with high poverty rates. This situation highlights the stark contrast between government-funded education, which poses a substantial burden on the state's budget and is often ineffective, and private school education, which prioritizes profit over the educational needs of its students and varies in effectiveness.

Higher education does not qualify for jobs

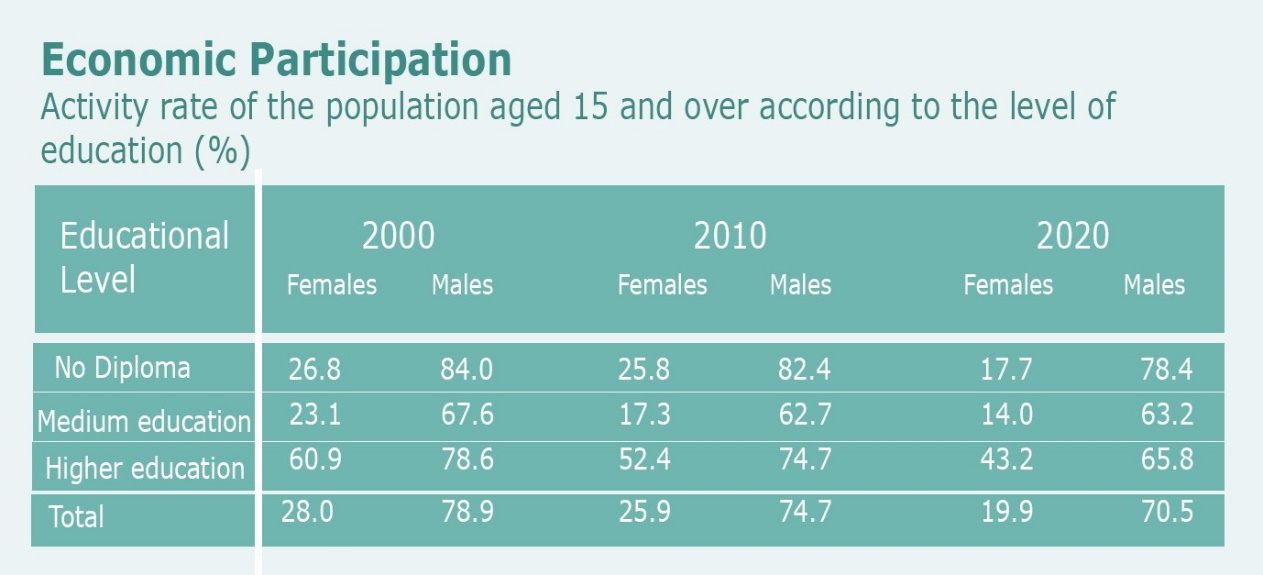

The assessment of educational quality can be ascertained through the employment opportunities available to students. As evidenced by a report from the High Commission for Planning, a reputable statistical authority, the 2023 unemployment rates for university graduates were 20% for men and 18% for women. This disparity is further pronounced for individuals with lower levels of education. Despite reviews of academic specializations in higher education, there has been no discernible improvement in job prospects. Notably, data on job attainment based on educational qualifications reveals a concerning downward trend across all educational levels, as depicted in the table below.

Source: Report of the High Commission for Planning for 2022 entitled: Women in Numbers[6].

However, many young people still believe in universities, which are still overcrowded and do not provide enough seats for everyone. In 2023, there were 432 universities in all forms, with a total of 1,170,000 students, including 1,060,000 in public university education and 34,000 in public training colleges like higher colleges of engineers, teachers’ institutes, and military academies, which leaves 75,000 students only in private higher education institutions.

Several indicators are available to assess the quality of educational services provided by universities, including the gender and age distribution of the academic staff. For example, there are 3,500 professors aged over 60, while the number of female professors out of a total of 15,800 is only 4,700. In private universities, out of 7,200 professors, only 2,700 are women[7]. Furthermore, despite an unprecedented number of Ph.D. holders, opportunities for them in university staffs are extremely limited. According to the Ministry of Education's statistics, the budget allocated to the education, scientific research, and innovation sector makes up only 7% of the state's overall budget.

The status of public educators

The government has approved a draft decree that outlines the fundamental framework for employees in the education sector. This decision has led to significant protests and dissent among sector employees. They argue that they currently face challenging working conditions and that the proposed framework fails to offer any improvements to their situation.

Teachers are often viewed as both the oppressed and oppressors in their profession. Although they face challenging working conditions, a significant number of them lack the necessary qualifications to carry out their roles as educators effectively. This inadequate level of education leads to ill-prepared graduates, and government training facilities are unable to address these shortcomings adequately. This situation is due to a combination of factors, including low educational standards, difficulties in compensating for these deficiencies, and poor planning. Moreover, the contracting system is another contributing factor to the unsatisfactory working conditions for both public and private education sector employees. Teachers are classified as contractors and are at risk of contract termination, unlike public employees who are not at risk of dismissal and enjoy various privileges.

The data points and metrics shed light on specific aspects, but their details present a bleak picture of this fundamental element of societal progress—education. These metrics offer insight into the reasons behind the stagnation observed across various sectors. How can individuals, emerging from a flawed educational system, effectively meet the demands of their respective fields? Ultimately, the responsibility lies with the government, as political determination is vital for initiating any kind of change within a societal framework. Subsequently, other factors come into play, including the societal barriers present within the broader population and the financial motivations of a select few. However, in the current context, where does this political determination originate? And how can educational reform be realized within a system that benefits from its own mediocrity?

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 19/12/2023

1- https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2023.pdf ↑

2- Moroccan students rank last in the results of an international study assessing reading levels, according to Hespress.

3- https://www.hespress.com/%D8%AA%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B0- ↑

4- The Ministry of Education's report on the sector's outcomes for the 2022/2023 school year, released on 4/5/2023.

https://www.men.gov.ma/Ar/Documents/Bilan%20MENPS%2022-23 %20AR%20-%20VF.pdf ↑

https://snrtnews.com/article/53240 ↑

5- Annual Report 2021 from the Competition Council.

https://conseil-concurrence.ma/cc/ar/wp-content/uploads//2022/10/Rapport ↑

6- Report: Women in Numbers, released by the High Commission for Planning in 2022.

https://www.hcp.ma/region-agadir/docs/docs/La%20femme%20marocaine%20en%20chiffres%2C%202022.pdf ↑

7- Ministry of Education's 2022/2023 Academic Year Outcome Report in Figures.

https://cutt.ly/kwDt2RpW ↑