This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Although the historical responsibilities for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and climate change vary among the countries of the world, the fate of those countries is one and the same, regardless of the degree of responsibility that falls on each. They are all exposed to climate change effects and they all bear the consequences. This requires that they take the necessary actions to mitigate those impacts and protect individuals and the environment from risks.

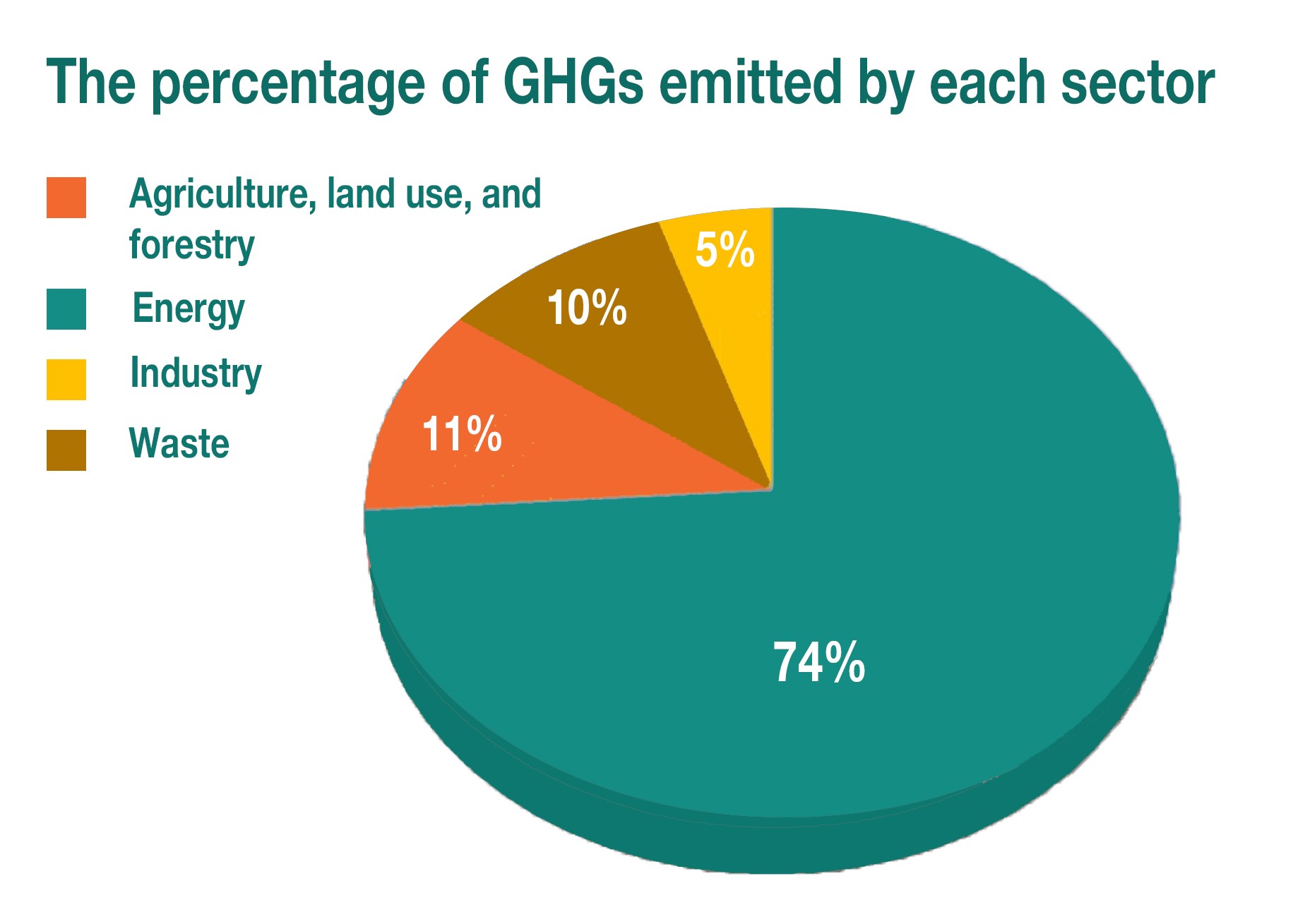

Algeria is one of the developing countries whose economy is mainly based on the oil and gas sector, which produces the largest share of GHG emissions. Based on 2000 data (1), energy consumption is Algeria's primary source of GHG emissions, responsible for a whopping 75% of the country's total emissions. Energy consumption emissions include those from production, transportation, construction, and manufacturing (about 46% of energy consumption emissions); producing, processing, and transporting of hydrocarbons (about 20%); and the liquefaction of natural gas (about 8%). The agricultural sector, land-use change, and forestry are responsible for 11% of the total GHG emissions. Waste management and industrial activities are responsible for 10% of total emissions: landfills emit 95% methane (CH4), and the cement industry emits 5% CO2.

Approved mechanisms

Algeria has been committed to participating in international efforts to mitigate climate change and its impacts since it ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) of 1993 (2). The treaty has established a global framework for intergovernmental efforts to confront the challenge posed by climate change; it has put forth a series of recommendations, some of which are mandatory and oblige each country to make regular statistics of national GHG emissions.

In this context, Algeria submitted its First National Communication (FNC) to the UNFCCC Secretariat in April 2001 and presented it at the seventh session of the Conference of the Parties (COP7) in Marrakech in December 2001. The report contained updates on national GHG statistics for 1994 (as a reference year).

Furthermore, Algeria presented its Second National Communication (SNC) at the fifteenth session of the Conference of the Parties (COP15) in Copenhagen in 2009, including a report that contained updates on national GHG stats for the year 2000.

The INDCs announced Algeria's plan to reduce national GHG emissions by 2030 by 7%, depending on domestic capabilities, and by 22% if international support were provided in terms of financial resources, transfer of technology and know-how, and capacity building. However, in the absence of regular stats on emissions, it is hard to ascertain whether or not this goal can realistically be achieved before the time limit.

On the institutional level, the most crucial implemented measure was the establishment an official body that addresses climate change in 2005, namely the National Agency for Climate Change (3). In implementing the outcomes of the COP19 (held in Warsaw in 2013), Algeria also submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) (4) on September 3, 2015. Notably, INDCs are the primary way governments internationally announce the steps they will take to address climate change in their countries. INDCs also address how each country is adapting to the impacts of climate change and what support it needs or will provide to other countries to adopt low-carbon pathways and build resilience to climate change (5).

Climate Change in Algeria and its Impacts

05-11-2022

The INDCs announced Algeria's plan to reduce national GHG emissions by 2030 by 7%, depending on domestic capabilities, and by 22% if international support were provided in terms of financial resources, transfer of technology and know-how, and capacity building. However, in the absence of regular stats on emissions, it is hard to ascertain whether or not this goal can realistically be achieved seven years before the set time limit.

International cooperation

Algeria has developed the National Climate Plan with the support of the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) to formalize the climate strategy in the country. The plan’s paramount objectives are to enhance the mobilization of water resources, combat floods, protect the coast, counter drought and desertification, and increase the resilience of ecosystems and agriculture to climate change. It includes two work programs. The first is a short-term action plan (2020-2025), which comprises 36 adaptation and mitigation measures that can be achieved during the next few years to respond to emergencies. The human capabilities and skills necessary to implement this action plan exist, but the main obstacle lies in obtaining financing. The second is a medium-term action plan (2020-2035), which includes 27 adaptation and mitigation measures that need more time and require strengthening the regulatory framework and the human and material resources for their implementation. Its application requires, in particular, coordination between the relevant sectors and the conduct of preparatory analytical studies.

As part of the partnership project with GIZ, the Algerian Ministry of the Environment conducted a study in 2017 entitled 'Supporting the National Climate Plan' on risks and vulnerabilities to climate change. The maps drawn as part of the study have shown levels of risk related to the inability to ensure basic food security for the population (grains and dairy products). This situation threatens the country's strategic reserves for hard and soft wheat consumption.

Climate Change: It’s About Time!

29-12-2022

In practice, only three projects funded by the National Fund for the Environment and the Coast (FNEL) in 2020 have been identified since Algeria launched the National Climate Plan. To test the adaptation and mitigation measures, three pilot regions, known in Algeria as “wilayas”, were selected to make these fragile states more resilient in the face of climate change impacts. These three regions are Sidi Bel Abbès, M'Sila, and El-Bayadh.

Third National Communication and First Biennial Report

The Third National Communication (TNC) on climate change complements the First and Second Communications. Its purpose is to report to the UNFCCC Secretariat on the progress made in the actions taken by each country to implement the treaty. Along with the First Biennial Update Report, Algeria has prepared its TNC with the support of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) to implement the decisions made at the COP17 held in Durban, South Africa.

Algeria’s TNC presents a summary of four reports (6) particularly, yet, in spite of all these documents and studies, no tangible steps have transpired on the ground. Most of the international assistance related to mitigating climate change is related to implementing plans, training, and skills development. We hardly see a tangible project that has to do with converting advanced technology into “clean” technology, for example, or establishing mechanisms that enable the relevant parties to identify, monitor, and track air pollutants. In order to set up projects which are more effective on the ground, the concerned authorities must make a reassessment of their needs and clearly communicate those to the funding parties.

The cost of action... and inaction

According to a study (7) by the Ministry of the Environment, the average cost of environmental damage and deficiencies resulting annually from human activity in Algeria amounted to about $11.7 billion, equivalent to 6.9% of Algeria’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2017. Climate change-related damage and environmental deficiencies in the energy sector amounted to about $4.9 billion annually, equivalent to 2.9% of GDP.

Despite all these documents and studies, no tangible steps have transpired on the ground. Most of the international assistance related to mitigating climate change is related to implementing plans, training, and skills development. We hardly see a tangible project that has to do with converting advanced technology into “clean” technology or establishing mechanisms that enable the relevant parties to identify, monitor, and track air pollutants.

Climate resilience measures require $1.11 billion yearly, whereas the budget of the Ministry of the Environment, which is responsible for national climate policy and fighting climate change, does not exceed $20 million.

Macroeconomic analysis has shown that climate resilience measures require 30% of annual environmental remediation investments or $1.11 billion yearly. It is the sum of necessary investments in the national economy that must be made by the government and its partners in the public and private sectors to ensure the country's resilience in the face of climate change. However, this amount falls far short of what can be done according to the current capabilities. Ironically, the Algerian Ministry of the Environment, which is responsible for national climate policy and fighting climate change, has the lowest budget among the ministries. Not excluding any of its attached bureaus and institutions, the total budget of the ministry does not exceed $20 million (8).

The reality of dealing with climate change

Algeria is the largest country in the Arab world and Africa by area. It is one of the most vulnerable places to climate change, whose impacts have recently been felt through the extremely worrisome rise in temperatures in the region. The slow implementation - or non-implementation - of Algeria's action plans has been the prevalent pattern, despite the country's potential and seemingly ambitious announced strategies and action programs. For example, Algeria has drawn up the National Strategy for Integrated Waste Management, accompanied by action plans, with European funding estimated at 1.7 million euros. However, no real change has been noticed in waste management policies, as the selective sorting system for household waste has not been implemented as was planned in the 2001 Act. Technical landfill institutions still suffer from a large amount of waste received and the narrowness of the trenches allocated to them, which often makes them look like arbitrary landfills. It is worth noting that organic waste dumps are considered some of the most important sources of methane emissions, which cause global warming, with the total absence of the technologies that allow the recovery of the organic gases they emit.

Within the framework of reducing GHG emissions from the energy sector, Algeria put forward the National Program on Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in 2015. The main objective of this strategy is to reduce the use of fossil fuels, expand the usage of renewable energy, and reduce total energy consumption by 9% by 2030. As part of this strategy, the concerned authorities have also implemented a regulatory framework to introduce thermal insulation for a housing program in five new cities. Applying these regulations was tested on a pilot basis during the construction of 600 housing units across the country. In addition, solar and wind energy, accompanied by medium-term production of solar thermal energy, will be deployed nationwide by 2030. The strategy also includes converting one million petrol-powered vehicles and more than 20,000 petrol-powered buses to run on liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). According to the latest statistics, the number of LPG-powered vehicles has reached about 500,000 (9), equivalent to 50% of the target number. Although it is a good indicator, it still represents only 7.5% of the total vehicles counted in 2019. That is in the absence of new statistics and amid the importation ban since 2017, which means that the number of cars has been relatively stable in the country.

The Algerian government has recently resumed imports with new regulations, which placed an importation ban on all diesel-powered vehicles. The move was welcomed by environmental advocates, although the motive was not environmental but purely economic, given the suspension of production of this type of vehicle in manufacturing countries. However, within the framework of the policy of encouraging the use of LPG and rationalizing expenditures, it was more appropriate to encourage manufacturers to install LPG kits in new vehicles instead of encouraging individuals and cab drivers to equip themselves with LPG kits by providing support for their equipment to the tune of 4.55 billion dinars (10).

It would have been better to impose LPG on service vehicles, such as officials' vehicles, administrative vehicles, and taxis, which are easy to operate. It would have saved the national treasury a lot, as the price of LPG is 9 dinars per liter and gasoline is 46 dinars per liter. It would have also contributed to reducing GHG emissions, as LPG is considered clean energy.

Meanwhile, the energy sector has implemented several measures aimed at reducing GHG emissions in oil and gas fields, such as installing reinjection compressors (11) and 32 flare gas recovery systems (FGRS) in the oil and gas fields. These measures led to reducing gas flaring by 42% over a 15-year period from 6.19 billion m3 in 2000 to 3.5 billion in 2015. The project of sequestration and storage of CO2 at the Krechba (Ein Saleh) deposit allowed the storage of about 4 million tons of CO2 between 2004 and 2011.

It was more appropriate to encourage manufacturers to install LPG kits in new vehicles instead of encouraging individuals and cab drivers to equip themselves with LPG kits by providing support for their equipment to the tune of 4.55 billion dinars. It would have been better to impose LPG on service vehicles and save the national treasury a lot, as the price of LPG is 9 dinars per liter, while that of gasoline is 46 dinars per liter.

The most crucial goal of the National Program on Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency is to use renewable energy to produce 27% of national electricity by 2030. However, after seven years, Algeria's exploitation of renewable energy has not exceeded 0.8% (12), and it is still almost completely dependent on fossil fuels. Algeria's capabilities place it at the forefront in terms of the volume of sunshine – Algeria receives an average of 2000 hours/year of solar radiation, and its south receives more than 3,500 hours. However, the use of this energy source remains modest, as the share of solar energy in 2017 reached about 0.69% of the total energy used, while that of wind energy did not exceed a meagre 0.02%.

Lack of legislation

Despite all these measures, and nearly twenty years since the first legal text concerning the environment and sustainable development was promulgated, it is remarkable that there is no direct law or executive decree on climate change in Algeria that can identify legal measures to be adhered to and determine punishment for violations or transgressions that cause this phenomenon to worsen. One of the most crucial pillars of environmental or climate action, in particular, is reliance on monitoring and oversight. However, we find that monitoring is strictly limited, and its mechanisms are almost non-existent for two main reasons:

-The small number of Environmental Compliance Inspectors (ECI) compared to the number of industrial establishments that require inspection, in addition to the fact that the ECI does not have the capacity of judicial officers. This means that in the event of legal violations, the ECI can only issue written notices without imposing any compulsory legal action.

-The environment and construction police are only concerned with the urban aspect, without focusing on the environment, which leaves the door open for violations by individuals and industrial institutions.

After seven years of launching the National Program on Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency, which aims to use renewable energy to produce 27% of national electricity by 2030, Algeria's exploitation of renewable energy has not exceeded 0.8%.

The rate of water wasted in Algeria reached 45% at the height of the drought crisis in the region in 2021. Waste due to leaks from run-down water networks in the capital alone accounted for about 30 to 40% of the total potable water.

In addition to the absence of control over the pollutants emitted by industrial institutions, there is also the bad habit of wasting water in Algerian society. The rate of water wasted reached 45% at the height of the drought crisis in the region in 2021. Waste due to leaks from run-down water networks in the capital alone accounted for about 30 to 40% of the total potable water. This added to the crisis and complicated the task of the official concerned bodies who struggle to find a solution to the random water networks. Scarce rainfall, meanwhile, has led to the drying up of dams, aggravating the entire situation.

However, one of the most significant obstacles to undertaking serious studies, accurate analyses, forecasts, and expectations for climate change is the lack of data related to GHG or air pollution. In 2000, the government established a national network called Sama Safiyah (Clear Sky) to measure air pollutants and determine air quality; however, the network has been out of service since 2005. Algeria thus lacks a mechanism for measuring air pollutants, and this kind of data becomes almost irretrievable on the long term, which has a negative impact on all climate studies.

For instance, the health sector is supposed to be the leading indicator of the implications of air pollutants or extreme weather events on the health of citizens, whether directly, as in cases of allergies, respiratory diseases, wounds, and disabilities resulting from floods and wildfires, or indirectly, as in vector-borne and water-borne diseases, which are caused by drought or high temperatures. Algeria has recently suffered from the effects of climate change (cholera in 2018, floods in 2020, and wildfires in 2021), but due to the lack of data, it is difficult to count the number of victims and link it to the causes.

One of the most significant obstacles to undertaking serious studies, accurate analyses, and forecasts for climate change is the lack of data related to GHG or air pollution. In 2000, the government established a national network called Sama Safiyah (Clear Sky) to measure air pollutants and assess air quality. However, it has been out of service since 2005, and there is no longer a mechanism for measuring air pollutants.

The health sector is supposed to be the leading indicator of the implications of air pollutants and extreme weather events on the health of citizens, whether directly. Algeria has recently suffered from the effects of climate change (cholera in 2018, floods in 2020, and wildfires in 2021). But due to the lack of data, it is difficult to count the number of victims and link it to the causes.

Climate change is a horizontal issue, in the sense that it sweeps all sectors and concerns all areas of life. It is imperative that the integration of this issue is activated in the work programs of all government departments, especially the education sector. We must instil in our children habits that can contribute to sustainable development and trigger a quantum leap in the way future generations deal with the environment and use natural and energy resources. Away from theoretical studies, it is important to take urgent, practical steps to combat climate change, whose effects are unfolding faster than the measures taken to confront them. Postponing that confrontation for a year, or even a month, comes at a heavy price.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 08/12/2022

1- Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning 2010.

2- Presidential Decree No. 99-93 issued in Official Gazette No. 24 of November 21, 1993.

3- Executive Decree No. 05-375 of September 26, 2005 establishing the National Agency for Climate Change.

4- Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) World resources institute.

5- https://www.wri.org/indc-definition

6- Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy website, November 2022, https://bit.ly/3VJK2dZ

7- Ibid

8- Finance Act 2022, https://news.radioalgerie.dz/

9- https://news.radioalgerie.dz/ar/node/8103

10- https://bit.ly/3W1BM93

11- https://bit.ly/3uzA82J

12- https://bit.ly/3iOu57D