This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

It was love at first sight for the Sudanese – the moment they first beheld a football being kicked around with agility and skill by the British invaders across the broad fields of the British encampments in Khartoum. The invading British army had accomplished its mission to “reconquer Sudan”, a campaign led by Major General Lord Kitchener Pasha in 1899, the first British Governor-General of Sudan. Football, however, managed to temper the storm of fire and blood, as the rumbling Maxim cannons quieted down, with horrific consequences in the aftermath of the invaders’ massacres against the Mahdists (1) (supporters of Imam Mahdi in Sudan and their own independent state, especially the Omdurman battle in September 1898).

Since then, football has taken the throne of sports in Sudan, capturing the hearts and minds of fans, who were so elated to the point of removing their turbans and setting them ablaze in excitement. This piqued the interest and attention of rulers and politicians, who then focused on football and tried to control it in every possible way – be it during the colonial period or under the rule of the Sudanese nation state, under both military and democratic regimes. The authorities turned to tactics of the “carrot-and-stick” to enforce their control, often resorting to retaliation when things didn’t go their way or whenever their attempts to tame the sport failed.

April 24, 1976 marked a tragic day in Sudan’s football history, as former Sudanese president Jaafar Nimeiry decided to pronounce football as a purely grassroots, non-professional sport, effectively dissolving all sports clubs and unions. The pretexts of this decision were some commonplace riots that broke out during a match between Al-Hilal and Al-Merrikh clubs, who were competing for the Health Revolution Cup. At the time, the Sudanese team was one of the most prominent in Africa, having won the Africa Cup of Nations in 1970 and almost qualifying for the World Cup in 1974.

Various attempts to advance Sudanese football have occasionally managed to yield positive outcomes, like when Al-Merrikh Club won the Africa Cup of Nations in 1989 and Al-Hilal Club reached the finals during the African Clubs Champions League in 2008, ending a 32-year absence from the cup. During the two African Championships of 2012 and 2022, the Sudanese team recurrently stood out, though such efforts remained sporadic and insufficient for building an organized athletic system that adheres to globally recognized standards.

Historic background

As things calmed down in Sudan, the colonial powers embarked on engineering the country’s social fabric. They introduced regulations into Saraya al-Hakimdar, now the Republican Palace, while the first Governor-General Lord Kitchener, armed with the vanity of “an empire where the sun never sets”, urban-planned Khartoum’s streets in a way that matched the stripes of the British flag and instructed the construction of new buildings in Victorian style. The eastern and western squares of Gordon College, currently known as the University of Khartoum, built in 1902, were designated as football playing fields. Football found its way into residential neighbourhoods in Khartoum, and especially into the Burri suburb, through the military encampments and the Gordon Memorial College, adjacent to the British army barracks.

The Burri Sports Club was founded in 1918. Omar Ali Hasab El-Rasoul, nicknamed Hasabu el-Saghir, was considered the team’s star; a top goal scorer in the history of Sudanese football. Hasabu el-Saghir scored the goal that won Sudan its only African Championship, against the Ghanaian team in the African Cup of Nations final, which was held in Sudan in 1970.

In the early 1900s, the clubs were encouraged, in the spirit of patriotism, to expand their organization of sports tournaments to support local activities. Education, which used to be exclusive to the ruling class and its entourage, became accessible through initiatives to build local schools, providing every Sudanese with an opportunity to receive an education. Sports clubs took sole responsibility over these initiatives, as political parties had yet to emerge.

From Khartoum, football crossed the river to Omdurman and into Wad Madani in central Sudan, which became the first city to welcome football beyond Khartoum, then into Atbara in the north of Sudan, an industrial city dubbed the capital of iron and fire. In other versions, it is said that the ball was kicked in Atbara’s pitches long before Khartoum’s, as the English army first landed there on its way to Khartoum to fight the Mahdists. Football then reached the east, around Port Sudan, the first Red Sea port. Later, following the arrival of British colonizers and the construction of railways, football spread into cities all over the country.

The Shurab Ball (a makeshift sock-football, made of socks stuffed with rags) was Sudan’s favourite game until 1910, and teams were created in the capital’s residential neighbourhoods. The game has since intermixed with politics. Having sensed the power football holds and its impact on people, the British banned sports in 1924 in the wake of the White Flag League (2) revolution and the assassination of the Egyptian army’s Commander-in-Chief and Sudan’s Governor-General, Sir Lee Stack, in Cairo. The ban included all sports in clubs and residential areas, and even included gatherings for weddings and funerals. Restrictions were gradually lifted, until their complete removal two years later, where, in 1926, sports clubs were allowed official registration. While security reasons were behind the decision to officialise sports clubs, (to pave the way for curbing political activity through sports), the Sudanese rushed to register their clubs, which bore various Arabic and English names. The most famous of those was the Stack Club, the first champion of Khartoum’s domestic league (1951), which changed its name into Tahrir Club (Arabic for “liberation”), following Sudan’s independence. In 1927, Al-Mourada Sports Club, the biggest of Sudanese sports clubs, was founded by Sudanese generals, and their team’s shirts proudly bore the military academy’s emblem.

As the Gordon Memorial College and the Sudanese Military College alumni found their way into sports club management councils, they rendered them into revolutionary incubators. Clubs were encouraged, in the spirit of patriotism, to expand their organization of sports tournaments and competitions to support for local civil activities. One such example is education, which used to be exclusive to the ruling class and its entourage. The Sudanese then took initiatives to build local schools – providing every Sudanese with an opportunity to learn to read and write. Notably, sports clubs took sole responsibility over these initiatives, as political parties had yet to emerge.

However, the British became wary of any moves carried out by the Sudanese. In 1936, for instance, the British authorities announced the formation of the Sudan Football Association, which was an astounding turning point; and yet, with it, they also aimed to block any attempt to form a national trade union to organise competitions. This happened once the British authorities learned that the Tithkar Club had called in the three clubs of the capital (Khartoum, Khartoum-Bahri, and Omdurman clubs) to form a confederate or a local association to organize sports tournaments in Khartoum. The initiative was initially supposed to be launched in 1933, but the Sudan Football Association had to wait for 19 years for the team (then known as Sudan’s Al-Ahli Team) to play its first game against Ethiopia in 1955. Dr Abdel Halim Muhammad headed the Sudan Football Association, and later became a member of the Sudanese Sovereignty Council (the presidential council) in 1956. The Sudan Football Association is considered the third co-founder of the African Football Association, established in 1957, alongside Egypt and Ethiopia.

The two poles of Sudanese football

Al-Merrikh and Al-Hilal Clubs were respectively founded in 1927 and 1930. The duo receives the biggest share of attention in the country, much like Real Madrid and Barcelona in Spain, or Al-Ahli and Zamalek in Egypt. The loyalty and passion of football fans have been divided between the two iconic teams, which also share the ancient Al-Arda neighbourhood in Omdurman. Al-Hilal stadium is located in the northern part of Al-Arda and is known as the Blue Jewel, while Al-Merrikh stadium is located in the southern part of Al-Arda and is known as the Red Castle. The two sworn opponents enjoy vast financial resources and large fan bases that pledge allegiance to their respective clubs.

Fans support their clubs individually or through collectives (by affiliation with fan associations across the country and abroad), which eventually developed into the Ultras Blue Lions, supporters of Al-Hilal club, and the Ultras Olympus Mons, supporters of Al-Merrikh club.

The Slums of Khartoum: On Life’s Edge

21-05-2022

Al-Hilal’s ultras have great influence over the playing fields and have produced a unique culture of fandom that fights injustice wherever it arises. Florent, Al-Hilal’s Congolese coach, acknowledged that the ultras “stand with us in the toughest of moments”, a sentiment echoed by Al-Hilal’s Malawian player, Gérald Ferry. Sudanese fans are known for their nonviolent approach, though tensions may escalate in the stands between Al-Hilal and Al-Merrikh supporters, sometimes turning into riots, violence, and throwing stones and empty bottles at players.

Ultras Blue Lions, supporters of the Sudanese Al-Hilal Club

Al-Hilal fans pride themselves on being the club of the Sudanese National Movement, although it was the first generation of college alumni who were actually the founding fathers of all Sudanese sports clubs. Al-Hilal is considered the first club in the Arab region to bear that name. Managements of sports clubs at the time comprised a mix of army officers, policemen, senior civil officials, diplomats, intellectuals, and middle-class merchants. In the 1980s, for instance, Al-Merrikh team was headed by the governor of the Central Bank of Sudan, Mahdi al-Faki, while the administrative officer, Tayeb Abdallah, became one of the most famous presidents of Al-Hilal club.

Now what?

During the last two decades, extremely rich businessmen, suspected to be corrupt, have taken over the management of sports clubs, especially of popular clubs, as management costs increased, perhaps in emulation of major European clubs. Al-Hilal was run by Salah Idris, Ashraf Sayid Ahmad (nicknamed “the Cardinal”), and, finally, Hesham Hassan al-Subat, suspected to be involved in corruption cases and the importation of non-conforming petrol ships.

Similarly, several Al-Merrikh presidents have been businessmen suspected of financial corruption, such as Jamal al-Wali, whose funds and estates received a confiscation order in 2019 from the Committee for the Dismantling of the June 30 Regime (a post-December 2018 governmental liquidation committee). The Supreme Court, however, overruled the committee’s decision following the military coup of the October 25, 2021.

Another Al-Merrikh president, Adam Abdullah (Sudakal), was sentenced to several years in prison in 2005 on charges of fraud and money laundering.

It was through this corrupt class that the National Congress Party, led by Al-Bashir, decided to infiltrate the sports sector. Attempts to take over football weren’t exclusive to the headquarters of the two major teams, al-Hilal and Al-Merrikh. Other cities were targeted as well by introducing protégés and generously supporting clubs to win the internal elections, which is what Ahmad Haroun, the North Kordofan governor, did with Al-Hilal Club.

Notably, Haroun has been charged by the International Court of Justice in The Hague for committing war crimes and crimes against humanity in Darfur in 2003. After four years behind bars, he fled prison, along with the Sudanese Islamist Movement leaders, as war broke out between the Sudanese army and the Rapid Support Forces on April 15, 2023.

During the past two decades, and as the costs of running sports clubs surged, extremely wealthy businessmen, often suspected of corruption, have taken over the management of popular sports clubs – perhaps in emulation of major European clubs…

Ultras groups are unbiased and have consistently distanced themselves from ethnic and regional conflicts. In fact, sports clubs have served as thresholds on which all racist and classist tendencies are discarded.

The security and intelligence systems have also taken over Al-Khartoum 3 Club, renamed Al-Khartoum National Club, before it reclaimed its initial name after the fall of Al-Bashir’s regime.

Attempts to co-opt the sports sector have all been in vain, however, and many Sudanese sports enthusiasts, especially football players and stars, have demonstrated their readiness to resist the regime. They have also expressed great sympathy with the martyrs of the popular protests, who were brutally suppressed by the regime. These passionate football supporters were notably present during the sit-in in front of the General Command of the Sudanese Armed Forces in Khartoum in 2019.

The fire of the revolution raged following the military coup of October 25, 2021. Every Sudanese citizen remembers that iconic scene of footballers taking a knee on the pitch before the commencement of the match between Sudan and Egypt during the African Cup of Nations in Cameroon in 2022. As they lined up for a group photograph before the match, the players raised their palms to read the Fatiha for the souls of innocent victims who were killed during the anti-coup popular protests.

As politicians, soldiers, and looters corrupted every corner of Sudan, many in the sports sector adopted an “injustice discourse”, feeling that those being toppled were also taking the money away with them, while they unabashedly sought to steal the dreams of the people. Fury intensified as the Sudan Football Association became a “mirror that reflected the country’s illnesses: dictatorship, classism, regionalism, and corruption,” (3) among others.

Perhaps one could mention here the chants recited against Al-Merrikh’s fans, “gatekeepers, gatekeepers, gatekeepers” after the Nimeiry regime was toppled in April 1985, hinting at the Nimeiry’s bias to Al-Merrikh club. Whether the accusation is true or not, Nimeiry has indeed shown great interest and passion for football throughout his rule, which lasted nearly 16 years.

December’s revolution: sports in the spotlight

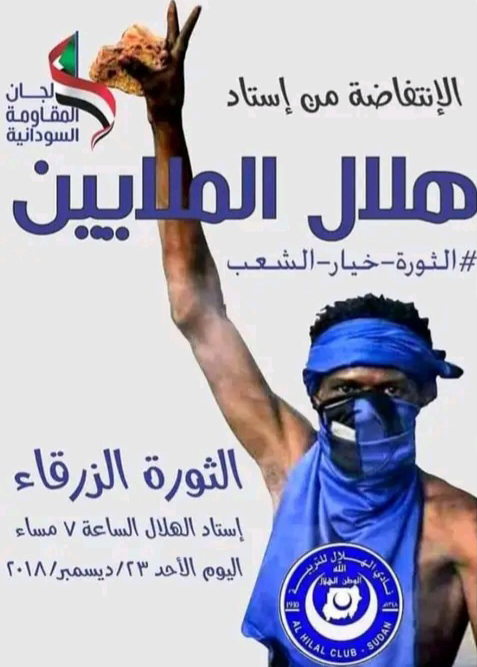

On December 23, 2018, as the revolution against Al-Bashir’s regime broke out, Al-Hilal ultras, known as the Blue Lions, came into the spotlight. In that historic moment, Ultras Blue Lions announced a sports’ revolution, capitalising on a match between Al-Hilal Club and the Tunisian African Club, who were competing for the African Cup.

All at once, voices chanting “the people want to topple the regime” reverberated around the Omdurman stadium and across the nearby neighbourhoods. In an unforgettable scene, football fans stormed the streets in mass protests just as the referee blew the final whistle, amid Al-Bashir regime’s brutal oppression.

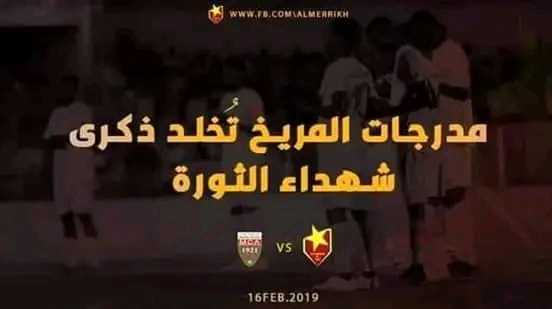

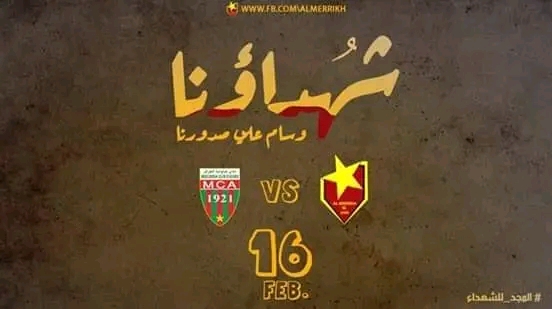

The part that Al-Merrikh’s ultras played in the revolution was just as significant. They turned their club’s stadium into an erupting volcano on February 16, 2019, during their team’s match against the Algerian Oran Mouloudia Club. Voices ripped through the quiet night with chants of revolution and change across Omdurman yet again. On Sunday, March 3, 2019, during the match between the Sudanese Al-Hilal and the Zambian ZESCO for the African Confederation Cup, the Ultras Blue Lions attended the match in black t-shirts, in mourning for the martyrs of Sudan.

The Sudanese national team’s and Merrikh Club star, Seifeldin Teiri, also came into the spotlight during that period for his participation in numerous marches and clashed with the brutal security forces. After Al-Bashir regime was toppled, Teiri was charged with arson at a police centre, liberating detained people, and burning cars, and was arrested in June 2019. This development alarmed the FIFA, which inquired after his legal and health conditions in prison. He was released on bail at the end of July, while the judiciary has yet to issue a final verdict in his case. In the meantime, Teiri plays as a professional footballer in the Egyptian league with Pharco Club.

All at once, voices chanting “the people want to topple the regime” reverberated around the Omdurman stadium and across the nearby neighbourhoods. In an unforgettable scene, football fans stormed the streets in mass protests just as the referee blew the final whistle, amid Al-Bashir regime’s brutal oppression.

The fire of the revolution raged following the military coup of 2021. Every Sudanese citizen recalls that iconic scene of footballers taking a knee before the match between Sudan and Egypt during the African Cup of Nations in 2022. As they lined up for a group photograph, the players raised their palms to read the Fatiha for the souls of innocent victims who were killed during the anti-coup protests.

Thirty years into Al-Bashir’s rule, these incidents proved that a barrier of fear had been shattered, inspiring ultras and supporters to show bravery and courage in the face of security forces and police brutality.

The pandemic and the devil’s lure

As the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, sports came to a complete halt in Sudan. Al-Hilal’s ultras thus channelled their efforts into various other domains. For example, they posted letters on the walls of the Ministry of Health and the Khalifa Courtyard. One of these letters addressed the doctors of the nation: “Our white army, we know what you’re going through. We’re with you and we shall overcome”. A second letter was addressed to Italy, the cradle of ultras around the world, which was suffering the full blow of the pandemic: “From Sudan to Italy, the cradle of ultras, we pray for you.”

In 2022, in line with other social campaigns, Ultras Blue Lions organized a futsal championship that bore the slogan “For a drug-free Sudan,” with the aim of fighting drug addiction in Sudan’s league, after a rise in drug use was registered among younger age groups, with the most commonly abused substance being the infamously fatal ice crystal, known as the Devil’s Lure. Similarly, the group organized fun activities in the Al-Hilal stadium for children with cancer (for the association “We’re all valued – We’re hopeful”), with the participation of Al-Hilal player, Abu Akleh Abdullah. Incidentally, Sudan is considered one of the countries with record levels of cancer cases.

Ultras and neighbourhood committees

Nasser Abou Baker, a Sudanese journalist who specializes in sports, says that the ultras in Sudan are bound by the ultras’ global principles; they therefore make no media appearances. Nevertheless, their solid self-organization, cohesion, songs, and chants, have all factored in tightening the fabric of “neighbourhood committees” and “resistance committees”. They have seamlessly merged with those revolutionary committees, seeking no credit for themselves.

Ultras groups are unbiased and have consistently distanced themselves from ethnic and regional conflicts. In fact, sports clubs have served as a threshold on which all racist and classist tendencies are discarded.

Sudanese poet, Dr Omar Mahmoud Khaled, describes it in the following verses as such:

We, in Al-Merrikh, are the closest of kin

The star is our one love and passion

And our differences in opinion

Only make us stronger, in thick and thin

Residents of Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, formed ultras groups within the city. They flocked to Khartoum from all over the country, driven by geopolitical, economic, and climate reasons, where their numbers grew exponentially, skyrocketing from nearly half a million in the 1980s, to almost ten million people in recent years. Consequently, the ultras also saw a significant boom in number. Supporters’ associations are currently equally spread throughout the country and abroad.

As the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, sports came to a complete halt in Sudan. Al-Hilal’s ultras channelled their efforts to other domains, posting letters on the walls of the Ministry of Health and the Khalifa Courtyard, addressing the doctors of the nation: “Our white army, we shall overcome”. A second letter was addressed to Italy which was suffering the full blow of the pandemic: “From Sudan to Italy, the cradle of ultras, we pray for you.”

In 2022, in line with other social campaigns, Ultras Blue Lions organized a futsal championship under the slogan “For a drug-free Sudan,” with the aim of fighting drug addiction in Sudan’s league after a rise in drug use was registered among younger age groups.

Ultras are highly committed to showing support for their clubs and maintaining complete independence from management councils, which distinguishes them from other popular fan clubs. In their desire to control fan clubs, management clubs have become increasingly concerned about the influence of the ultras, particularly because of the ultras’ courage in expressing strong opinions about the ins and outs of their respective clubs.

Football in Egypt: Where People Find Solace

08-06-2023

Football in Iraq: A Game of People and Politics

02-06-2023

In an attempt to curb political chants and songs, some countries have banned open tournaments or restricted public entry into stadiums under the pretext of security. This was also the case in Sudan, where tournaments were held without spectators once the revolution against Al-Bashir’s regime began. Ultras groups were also subjected to harassment with the tacit approval of club managements, as the latters are affiliated with the ruling regime and prioritized safeguarding their own interests. For instance, in November 2019, Al-Hilal’s president, known as “the Cardinal”, prevented the club’s ultras from entering the club’s stadium, leading to fierce opposition against his leadership. The ultras issued a furious manifesto, vowing to spare no effort in “driving away any intruders, parasites, or corruption from Al-Hilal’s pure entity”. They affirmed that “Victory means liberating ourselves from the pockets of corrupt capitalism, which pays a few tainted pennies in exchange for massive propaganda and a few victories, disregarding the club’s dignity, which has been completely abandoned in these dark times. This system forsakes the values, heritage, and noble principles upon which Al-Hilal Club was founded. We solemnly swear to safeguard our club using every possible means, even with our own lives, if need be…”

Likewise, Al-Merrikh’s ultras have stood firmly against the Rapid Support Forces’ leader, Mohammed Hamdan’s (Hemedti) intervention to carry out maintenance work at Al-Merrikh’s stadium. The ultras said that they owed this stance to their martyrs Qussai, Abdul Azim, and Mohammed Majzoub, who were shot during the events of the December 2018 revolution. A banner they hung at the club’s entrance on March 27, 2022 read: “No to whitewashing murderers at the club’s expense”.

In the meantime, it appears that the ambitions of the wicked coalition of power, capital, and weaponry to exert control over sports and their supporters have been faltering, thanks to the most confrontational generation of supporters in the history of Sudanese football. The songs and chants they passionately deliver demand justice and retribution for the unarmed civilians and nonviolent protesters who had been brutally massacred. The most famous of those chants proclaimed: “Blood must be avenged with blood. We will not accept blood money!”

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 25/05/2023

1- As documented by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in his memoirs, The River War, as he accompanied the invading army to Sudan as a war correspondent.

2- The 1924, revolutionary events were concentrated in cities and led by public employees, laborers, and soldiers. The revolution called for the end of colonialism and unity across the Nile valley, and it coordinated with the Egyptian Liberation Movement.

3- In the words of Mohamed Rami Abdelmoula in his article “In Tunisia: Power and the Public Contend over the Football Field”, Assafir Al-Arabi.