This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The growing rate of negative climate change effects and their subsequent implications, especially the precarity of the State and political instability, indicate a qualitative leap in Sudan’s climate configuration. It raises serious questions about the future of the country’s natural resources, often perceived as a reserve that can help develop Sudan into becoming a breadbasket, at least regionally.

Symptoms of climate change are many and range from floods and inundations to the very opposite: droughts and rising temperatures.

Political, economic, and social implications are also at stake, most prominent of which is the massive social migration of farmers and herders in search of wealthier places. Other symptoms include movement towards urban centres, in search of housing and work, which robs agricultural areas of their workforce and overburdens cities with added pressures on their infrastructures.

Sudan’s case is exemplary of climate change, its ensuing instability, and ecological effects. Atmospheric turbulences are on the rise, as Sudan’s climate vulnerability grows, despite the country’s abundance of natural resources. According to a number of studies conducted between 1961 and 1990, the temperature has been increasingly rising. It is expected to warm by 1.1 to 3.1°C by the year 2060, where the most affected areas will be the deserts and semi-deserts, including the Nile River, Northern, and Red Sea states in Sudan. During the period (1961 to 1990), decreased rainfall was equally noted, as was a change in the number of rainy days, delayed autumns, alongside longer periods of drought. The probability of a climate shock thus rises as flooding and rain arrive faster and without an autumn break, which threatens farmlands and, consequently, the living conditions by which the majority of people are bound.

Sudan is located in an area considered one of the most affected by climate change. One of the reports (1) even noted that vast areas of Sudan could become unfit for human life, which would lead to mass migration towards urban areas, namely the Nile and its tributaries. These areas would then become under much bigger pressure than they are capable of handling – as these urban spaces are already fragile and suffer from a housing crisis and problems with potable water infrastructures, and other services.

Despite losing some of its land due to the separation of South Sudan in 2011 (its overall area is now down to 1.8 million km2), Sudan still has wide-ranging climate and ecological diversity. Its temperatures range between 26 and 42°C across five main climatic zones: the desert, which annually receives an average of 75 mm or less of rainfall; semi-deserts, where rainfall ranges between 75 and 300 mm; the low-rainfall Savana, where rainfall ranges between 300 and 800 mm; the heavy-rainfall Savana, where rainfall ranges between 800 and 1500 mm, and, finally, the mountainous area with large vegetation, with an average rainfall between 300 and 1000 mm per year.

According to a number of studies on temperature that were conducted between 1961 and 1990, it was noted that the temperature averages have been increasingly rising. It is expected that by 2060, the average temperature will warm by 1.1 to 3.1°C.

Sudan is also one of the countries which are most prone to waning vegetation, otherwise called desertification. Many have shown interest in the phenomenon throughout the past century, though the official plans to counter it have been significantly slowed down for various reasons: incapacity, failing to implement plans, and political instability. It is therefore estimated (2) that Sudan has lost between a quarter million to a 1.3 million hectares of vegetation and forest cover during the past twenty years. This has resulted in the deserts and semi-deserts taking up more than two thirds of the country’s area.

The western areas of Sudan, especially Darfur, have been successively hit by droughts ever since the mid-1960s, as rainfall ranged between 100 and 600 mm per year. Besides the drought, other elements have factored in accelerating desertification, including the significant population growth, elimination of the natural vegetation cover, and land clearance for farming without conserving the natural flora (especially since the areas being cultivated are neglected come next season, as farmers head to cultivate other areas). In the meantime, trees are cut down, whether for fuel use or other objectives, without making sure that other trees are planted in their stead. Some estimates (3) note that around half a million trees are cut down every year, including acacia, which produces Arabic gum.

Those areas, especially Darfur between 1980 and 1984, have gone through rough patches of drought. In fact, those years were but the peak of a succession of droughts of varied length and intensity, which have characterised the period ranging from 1967 to 1973. They were even followed by other consecutive droughts between 1987 and 2000. A UN Environment Programme study (4) estimates that, during those 17 years and in an area of 90 to 100 km2, about a third of the forests were lost, vegetation covers declined, and the semi-desert area expanded towards the south across various areas in Sudan. A 1975 study (5) has noted that the desert is expanding at a rate of 5-6 km to the south every year.

These droughts have impoverished the soil and vegetation cover, as large-scale grazing expands with the increasing numbers of livestock, and as over 70% of the population relies on land for agriculture and farming. However, with the decline of natural resources, conflicts between farmers and shepherds have been on the rise, and have even been considered one of the main reasons that drove the conflict in Darfur. The latter erupted in 2003 after brewing for long decades because of the consecutive droughts and desertification in the area. Former UN Secretary, Ban Ki-moon, described the conflict in Darfur, which had reached the Security Council then, to be the first ecologically-driven conflict.

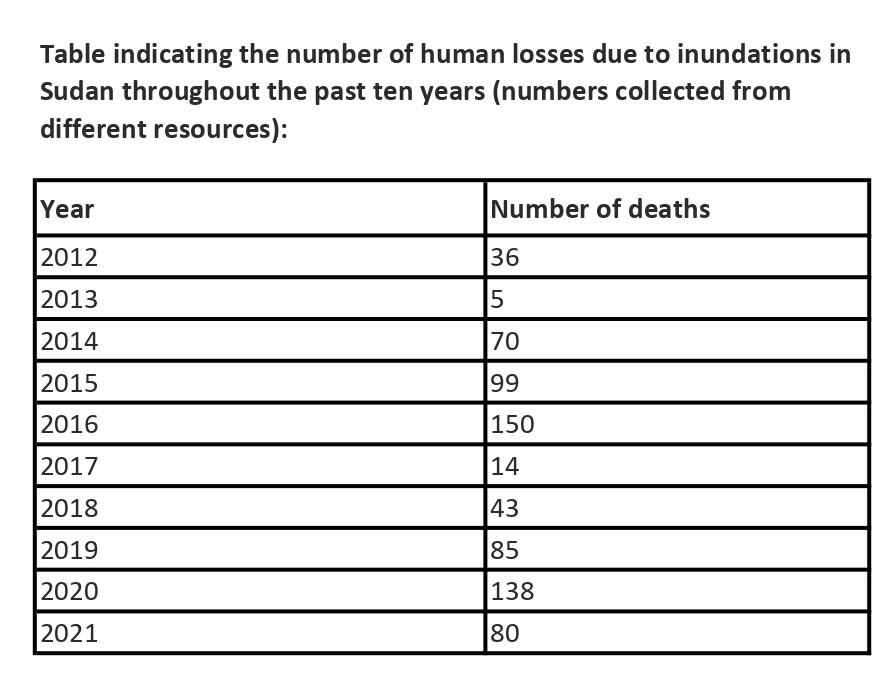

In truth, the issue isn’t the result of declining farmlands and grazelands for climate reasons only; it is also the result of mismanaging land and water resources all throughout the past seven decades, ever since the country’s independence – with over half the population under the poverty line. Nothing can better demonstrate such failure than the recurrent flooding disasters and inundations, the expansion of affected areas, and the worsening catastrophes year in year out. In parallel, the consecutive governments’ one and only concern has become to look for foreign aid to counter these disasters, which seem to take the state officials by surprise every year.

The evaporation of the Nile’s waters, its tributaries, and other rivers is yet another element at hand, especially with the hydrological irrigation projects and their effects on water flow. Water flow is expected to increase in the upcoming decade, after which it would begin to recede, all the way until 2050. Undoubtedly, this has implications on economic, social, developmental, and service-related activity in the areas by the riverbanks and those that rely on regulated irrigation.

Flood season

The period between June and September is considered a critical time in Sudan, as river levels and Nile levels rise following floods, which usually result in massive human and material losses.

For the majority of the Sudanese, 1946 is well imprinted in collective memory, as the population witnessed one of the most violent floods of the Nile. That year became a landmark by which people dated social occasions such as child births, marriages, and funerals, alongside other public occasions. Unsurprisingly, that year saw the Nile’s levels rise like never before, with its waters reaching 17.14 m3. It caused vast destruction and human and material losses, the details of which are still fresh in the Sudanese collective memory. The flood even headed north all the way to Egypt, almost inundating the Delta.

Decreased rainfall is noted, as is a change in the number of rainy days, delayed autumns, alongside longer periods of drought. The probability of a climate shock thus rises as flooding and rain arrive faster, which threatens farmlands and, consequently, the living conditions by which more than 70% of the population are bound.

That flood, which shocked everyone, lead to spontaneous reactions by those affected – they did whatever they could to set up barriers to block the gushing waters, with almost purely popular efforts. This is what the folk song, whose author remains anonymous, commemorates:

I admired them as they came tonight

To block the sea and stop the plight

The song talks about the tiny Island of Tuti, in the midst of the capital, Khartoum, and how its people resisted the waters that overflowed into their lands and homes, like that employee who took off his uniform and tied it to make it into a bag, packed it with soil, and used it to fill one of the holes. The singer Hamad al-Rih, one of Tuti’s residents, revived the song, which dates back to more than 70 years, and it has since been coupled with the flood season that hits the country for three months every year.

The flood phenomenon popped out of the history books and into reality. It became another regular climate phenomenon with which one coexists, and whose repercussions, often catastrophic, one simply accepts. One catastrophic moment took place in 1988, as the flood levels rose to 15.68 meters and claimed 76 lives, leaving behind hundreds of injuries and other material losses. 2013 brought yet another flood that surpassed that of 1946 in its intensity; it reached 17.4 meters and claimed 50 lives, according to official numbers, while 300 thousand people were injured and a quarter million houses were destroyed. Five years later, it would happen again, where 23 people lost their lives, more than 200 thousand were injured, and around 20 thousand houses were destroyed. The 2020 flood broke the records of 1946 and 1988, as the Nile River’s levels rose to approximately 17.66 meters, taking 138 lives and impacting more than half a million people in one way or another, not to mention material losses. Last year, according to UN figures, around 315 thousand people were affected. During the autumn of 2022, 15 of the 18 Sudanese States were struck by rainfall, floods, and inundations, which reached areas that weren’t subject to climate variability before. Ways to control flood waters became the very core of the discussion around Ethiopia’s Al-Nahda Dam, as some saw that it would help benefit Sudan.

Sudan is one of the countries that are most prone to desertification. One of the reports even noted that vast areas of Sudan could become unfit for human life, which would lead to mass migration towards urban areas, the Nile, and its tributaries. These latter areas would then become under much bigger pressure than they are capable of handling.

With the decline of natural resources, conflicts between farmers and shepherds have been on the rise, to the point that they are considered one of the main reasons that drove the conflict in Darfur, which broke out in 2003 as a result of the consecutive droughts and desertification in the area. Former UN Secretary, Ban Ki-moon, has even described the conflict in Darfur to be the first ecologically-driven conflict.

The floods that inundated El-Manaqil area in Central Sudan received wide popular and media attention, which took on political dimensions – given the scale of the disaster that hit the area and its people, coupled with official negligence. Some engineers who studied the satellite images saw that the area had been hit by sudden floods resulting from a heavy downpour in the southern areas, which ran down the lowlands all the way into El-Manaqil. And yet, some irrigation engineers note that there was some degree of negligence. Since August of 2022, a gradual increase in water supply was supposed to take effect for the waterways that irrigated Al-Jazirah Project and El-Manaqil. This would have reduced the quantity of water in the Sinnar reservoir, which supplies water through the two main canals that irrigate Al-Jazirah lands. The result would have been more room to receive the extra rainfall water. This should have been conducted halfway through the month to maintain zero levels as rainfall increases; however, and as per usual, none of that happened. Likewise, some of the drains never received the required maintenance, and weren’t even cleaned up. This is how canals became unregulated water reservoirs when the floodwaters circled the villages and lowlands.

Climate change surfaced in public discourse throughout the past three decades as some phenomena kept recurring (be they droughts, floods, or inundations), bringing along political, social, and, finally, security implications. Besides, Sudan is often featured in environmental and climate change studies that address the African continent, be it for the Horn of Africa, North Africa, or Arab regions, as Sudan has a share in both Arab and African worlds. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), which comprises East Africa countries, including Sudan, has set up a climate forecast center and early warning services following its prediction last June that autumn would be different this year around.

The Triangular Capital of Khartoum, with its twin cities of Omdurman and Khartoum Bahri, is considered a special case in terms of climate questions –it lies within the African plain and coast and in a much lower area. It is therefore considered a natural pathway for gushing waters, with its topography that allows the meeting of the White and Blue Nile, forming the Nile River, before it continues north towards Egypt.

Due to its urban appeal as a capital and a centre for political, economic, and social activity, Khartoum has become home to around eight million people who live in its area – estimated to be eight thousand square meters. These people have their own activity, consume fossil fuels, and operate all sorts of machines that eject fumes from car exhausts, factory machines, and air conditioning… This ends up forming a giant cloud made up of CO2, dust, and water vapour, which fogs the skies of the capital all day long and maintains high temperatures until nightfall.

Private property

On the other hand, conflict over resources has resulted in a shift in social relations. Farmers’ and herders’ private property became the new base upon which social relations are built; it replaced previously common customs, where such resources were considered public property for local communities. As such, it became important to receive permission from owners before exploiting land, lest it be perceived as trespassing private property. Any such event, therefore, led to strife, which, in turn, helped keep the Darfur conflict aflame – despite the presence of United Nations forces, (whose number is estimated to have reached tens of thousands, and whose presence, which lasted 13 years, was maintained by billions of dollars). The cycle of violence continued and peaked last year, in 2021, with 260 thousand displaced people – four times the number of displaced people in 2020 – notwithstanding the overthrow of former president Omar al-Bashir, accused in the International Court of Justice to have committed genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur.

The impacts of climate change are clearest in Darfur, with the prolonged drought season, the rising temperatures, and the unpredictable rainy season – which have all been detrimental to life development and population mobility. Although the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement lists articles that guarantee the displaced return to their villages, many of those who returned found that their areas and villages had been occupied by other people, which adds a new layer of complexity to the already complicated situation, with political, economic, and social implications.

Some studies conducted by Marshall Burke (6) clearly linked climate change in African countries south of the Sahara to the outbreak of civil conflicts, which took on various forms. The studies, backed by statistics, reached the conclusion that a one-degree-Celsius rise in temperature increases the potential for conflicts and civil wars by 4.5% that same year and by 0.9% the following year. By observing 18 climate models, the study (7) predicts that, by 2030, climate change could result in a 56% increase in regional conflicts, as the economic implications of natural phenomena on land remain unclear, be it the rising temperatures, droughts, rainfall, and any flooding that may ensue.

The issue isn’t the result of declining farmlands and grazelands for climate reasons only; it is also the result of mismanaging land and water resources throughout the past seven decades, ever since the country’s independence – with over half the population under the poverty line. Nothing can better demonstrate such failure than the recurrent inundations, the expansion of affected areas, and the worsening catastrophes year in year out.

Floods have become another climate phenomenon with which one coexists, and whose repercussions, often catastrophic, one simply accepts. During the autumn of 2022, 15 of the 18 Sudanese States were affected by rainfall, floods, and inundations, which reached areas that had never been subject to climate variability before.

With the vast majority of the population reliant on land for their livelihood– by working in agriculture and farming – and as desertification increases and rainfall decreases, the chances of providing help or support to this group of the population seem to be dwindling. It is no surprise then that a report by one of the international organizations (8) notes that Sudan now ranks 98 of 113 countries in the Global Hunger Index.

As droughts increase and dubious relations of production prevail, to the detriment of village folks and rural areas, many of these areas’ residents migrate to nearby cities and to areas close to the Nile and its tributaries looking for a living – and so urban populations grow. Upon Sudan’s Independence, the rate of urbanism among the population amounted to 18.5%; it rose to 29.8% in 2008 and kept rising to reach 35.59% last year, in 2021.

Yemen: Instability Hits the Climate Too

09-11-2022

Climate Change in Algeria and its Impacts

05-11-2022

While the first census showed that the number of urban agglomerations in Sudan was 68, the number rose to 115 in the 1983 census, and to 122 in the 1993 census, which proves that rural areas are clearly losing residents to the city. One of the results of this unregulated migration, in which lack of security and political instability played and still plays a role in conflict-ridden regions, is that newcomers build their own houses in an unregulated manner, sometimes in lowlands that are prone to flooding and, so, become part of the tragedy that befalls the country every autumn and winter.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 06/10/2022

1- Climate change could render Sudan 'uninhabitable' - CNN- https://www.cnn.com/2016/12/07/africa/sudan-climate-change

2- Combating Desertification in Sudan: Experiences and Lessons Learned- PDF. By Sarra A.M. Saad, Adil M.A. Seedahmed, Allam Ahmed, Sufyan A.M. Ossman, Ahmed M.A. Eldoma.

3- Desertification in Sudan, Concept, Causes and Control. By Abd Almohsin Rizgallah Khairalseed, University of Sinnar, Faculty of Agriculture.

4- UNEP (1992), Saving Our Planet: Challenges and Hope, the State of Environment 1972-1992, Nairobi, UNE.

5- Combatting Desertification in Sudan. Ibid.

6- A Professor in Stanford University.

7-Climate, Conflict and Social Stability: What Does the Evidence Say?

8- 2017 Global Hunger Index: The Inequalities of Hunger, by International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington.