This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Political instability and a rentier mentality that inspires many political socioeconomic policies, have been the main features characterising the ruling elite’s performance in Sudan over more than six decades. Their policies held contradictory approaches, from a prevailing public sector to enabling privatization policies which are devoid of any professional dimension, while also implying political enabling. This led to a state of impoverishment, creating hotbeds of political, economic, and social unrest that would blow explode as insurgencies which sometimes resorted to the use of arms. Most important though has been these policies’ failure to turn Sudan into a “bread basket” for the Arab world, or to even feed the Sudanese people themselves. This created the first spark that launched the ongoing December-April revolution, initially triggered by lifting bread subsidies, which later expanded to target the entire political system.

The practices and outcomes of such mentality manifest in three main sectors: oil, gold (and their production, extraction, and exportation), and agriculture. A rentier mentality has shaped how these three resources are approached. The Salvation regime was premised on an Islamist platform that overprized its international network at the expense of its national grounds. Likewise, as it would sympathise with Gaza and Rohingya Muslim children, disregarding Darfur’s suffering by the same governmental forces, it would sow more interest in generating quick revenues off of its resources, though at the expense of depleting them. What proves the former is that once the country prospered in petrol, interest in its agricultural sector declined. In fact, the sector only deteriorated during the petrol boom, and never in the years before it.

Agriculture in decline

Post-independence agri-politics have followed the same path, inherited from colonial times – whereby Al-Jazira Project, which produces cotton to supply fabric manufacturers in Lancashire in Britain, the backbone of the modern irrigation sector. It also generates hard currency for the public treasury. The biggest development happened when around one million acres were added to the project, known by El-Manaqil Extension, where the majority of rain-fed agricultural plans, upon which the vast majority of the population depends, were ignored. Furthermore, its area compounded the irrigated farming projects areas. When mechanized agriculture was introduced into traditional and rain-fed farming sectors, the policies that ensued, supported by the World Bank, have only had negative implications. Prioritizing senior state officials and army officers or on-ground workers with permits (even if they weren’t locals to the area) as well the intensive land exploitation, have both drained and impoverished the soil. Those have also intensified popular anger, which took rebellion and violence as a path, as had happened in the region south of Kordofan.

Similarly, the foreign investment promotion policy in agriculture has only exacerbated the situation – in its pursuit of turning Sudan into the bread basket of the Arab world. Many Arab and, specifically, Gulf investments were given disproportionate privileges. They were gifted thousands of acres, often at the expense of local populations, which ate away at even more of their rights, as traditional and irrigation agriculture comprise their two main sources of work and livelihood. As these agricultural investment areas are situated in rural regions that lack infrastructure and services, those investors had to contribute to that aspect, while the governmental policies have helped them out with many exemptions and offers, such as renting out the land for a nominal fee (like paying no more than 50 cents per acre), free access to water, and exemption from taxes at the beginning. These attempts to encourage investments succeeded in luring in a Bahraini company for instance, which acquired agricultural land that nearly equals the entire area of Bahrain. Likewise, one thousand end-of-pivot sprinklers were set up for a Lebanese company, using nearly half of the Lebanese population’s water consumption. An Egyptian company (that later halted operations) also obtained authorization to use 750 million m3, that is, around 4 percent of Sudan’s share of the Nile’s water. Were these waters given at market price, the company would have had to pay no less than one million dollars.

Many Arab and, specifically, Gulf investments were given disproportionate privileges. They were gifted thousands of acres of land, often at the expense of local populations, which ate away at even more of their rights, as traditional and irrigation agriculture comprise their two main sources of livelihood.

Governmental policies have helped them out with many exemptions and offers, like renting out the land for a nominal fee, free access to water, and farming fodder, which is prohibited in several countries because of its large water consumption. Sudan has also served as an ideal location, just 350 km away from the Red Sea, where agriproducts could easily be exported.

Saudi companies like Nadec, Al Safi, and Almarai and Emirati companies like Zayed Elkheir Project and Amtar also got excited about going to Sudan, where they could farm fodder crop and make up for the prohibition of farming those in their own countries, as they consume large quantities of water, so scarce in Gulf countries. Sudan has also served as an ideal location, just 350 km away from the Red Sea, where agriproducts could easily be transported to ports for export. Clover could be harvested every 30 days and moved to Port Sudan in no more than seven hours.

Such expansion resulted in tensions between farmers, shepherds, and local populations and foreign investors, be it related to roads, right to lands whose legal status hasn’t been regulated to guarantee the local population’s rights, or to the activity these companies carry out in exports, which has led to a spike in fodder and foodstuffs prices. All these factors have helped forge a path to revolt, which broke out in the latest December-April protests, resulting in the overthrow of former president Omar Al Bashir.

Petrol

Extracting and importing petrol is a textbook example of mishandling resources and empowering short-term political goals over strategic economic and social planning. Despite discovering oil in the 1970s, its production for exports or local consumption wouldn’t begin for until two decades later. Led by Al Bashir, the Salvation regime has managed the breakthrough that Jaafar Nimeiri’s, Abdel Rahman Swar al-Dahab’s and Sadiq al Mahdi’s governments failed to manage.

This paralleled an internal and external opposition to the Salvation regime and policies, which entitled it to this precious commodity and its revenues in hard currency. The regime focused on using those revenues to buy political allegiances and consolidate its security arsenal. The latter’s expenditures grew to reach nearly 70 percent of the state budget, leaving the rest to all sorts of services and developmental projects. Furthermore, the productive sectors didn’t enjoy the same chance agriculture did, with any significant investment, where the al-Jazirah Project was left to collapse as the funds allocated to renovate its infrastructure were minimal – that is, even though the official discourse goes by the slogan: “Agriculture is Sudan’s actual petrol”.

Extracting and importing petrol is a textbook example of mishandling resources and empowering short-term political goals over strategic economic and social building.

Where have the petrol revenues that entered the public treasury gone? These are revenues that range between 30 to 35 billion dollars, besides the 12 billion that were channelled into the southern government.

The petrol extraction process followed the same mentality of exploiting available resources, while failing to consider environmental impacts or local communities. Many issues then ensued, which the peace agreement between the government and the SPLM attempted to resolve in 2005, stipulating that 2 percent should be allocated to productive states, as well as defining measures to deal with the negative environmental impacts. All that, however, remained ink on paper, and the ever-rightful question remained: where have the petrol revenues that entered the public treasury gone? Revenues that range between 30 to 35 billion dollars, besides 12 billion that were channelled into the southern government. Even some of the major infrastructure projects, like the Marawi Dam, were funded by separate loans, mainly by Arab funds.

Lack of transparency was one phenomenon that accompanied petrol extraction. The challenging and confrontational state in which the Salvation regime found itself could explain such an approach, as it faced domestic and international pressures, and more specifically US sanctions. Mystery reigned supreme all throughout the different stages of raw material production, export, and refining. Everything connected to the petrol industry was thus rendered into a security issue, especially since the bulk of petrol is located in South Sudan, where the revolt took centre stage, and since SPLM, which led the revolt, clearly announced that the petrol facilities would be considered military targets were a political peace agreement not be reached. However, even after the peace agreement was made, the same practices were maintained, though shrouded in mystery and secrecy.

Gold

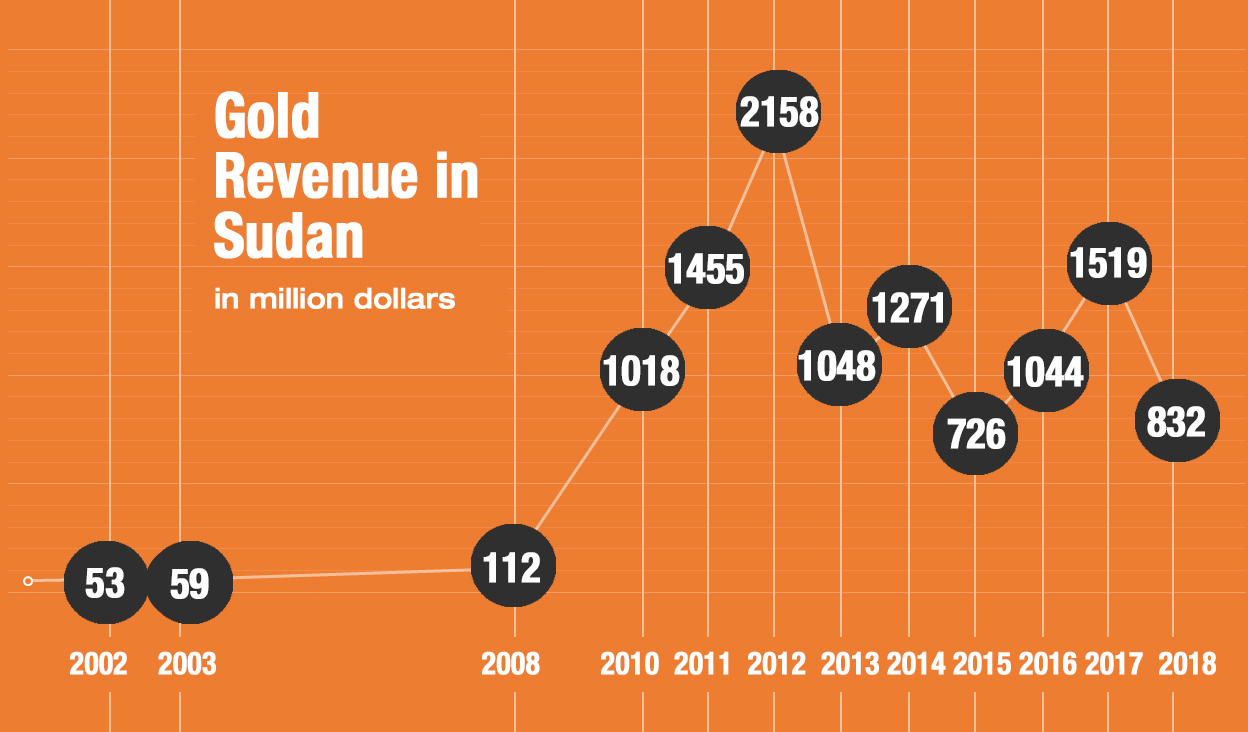

Gold production in Sudan is rooted in ancient times; it goes all the way back to the Kingdom of Marawi. Looking for gold was also behind the Muhammad Ali Basha campaign to invade Sudan in 1821. Sudan kept producing negligible quantities through private activity, until modern production took off in 1990, when a French company partnered with the Ministry of Energy and Mining under the name of Ariab, and managed to raise production to reach nine tonnes in 2009. Following the South Sudan split from Sudan, transforming into its own independent country in 2011, gold digging operations picked up to try and find new sources of foreign currencies to compensate for the petrol revenues that crashed with the split. Looking for gold would thus take place through traditional mining carried out either by individuals or Ariab and other companies, which boosted production to reach 73 tonnes in 2014.

According to the five-year economic programme of 2015-2019, set up to absorb the southern split shock and the missing petrol revenues, the mining sector would be considered the country’s generator of economic growth. The action plan stipulated that production be raised to reached 103 tonnes, by facilitating bank and private funding. Currently, Sudan ranks third in Africa in terms of production and gold exports, right behind South Africa and Ghana. It is estimated that there are around 132 companies that work there, including 15 foreign companies.

The increased gold prices in the international market have drawn in many miners, once estimated to be a million. Despite the increased volume of gold exports, with revenues sometimes exceeding two billion dollars, only a small percentage would reach the state budget – due to unfair policies, with central bank’s monopoly over gold sales. As gold rates are determined by the dollar exchange rate, the Bank of Sudan would purchase gold at the black-market rates and sell it to the Ministry of Finance according to governmental rates, which are the lesser rates. As the two rates are disparate, the Central Bank of Sudan would make up for the difference by printing currencies, a process that cost it an estimated 1.8 billion dollars between 2009 and 2015. Likewise, this very policy increased inflation rates, which reached 70 percent, according to official numbers.

The Bank of Sudan monopolised gold sales. As gold rates are determined by the US dollar exchange rate, the bank would purchase gold at black-market rates and sell it to the Ministry of Finance according to the lesser governmental rates. As the two rates are disparate, the Central Bank of Sudan would make up for the difference by printing currency, a process that has cost it an estimated 1.8 billion dollars between 2009 and 2015.

The IMF intervened, critiquing such a method. However, as the regime itself was home to such centres of power, these policies would be maintained, enabling some private companies to export gold. The biggest share of production, however, would happen through smuggling gold into Ethiopia, Eretria, Chad, and the United Arab Emirates. The United Nations report notes that, between 2010 and 2014, gold smuggling is valued at 4.5 billion dollars, especially into the United Arab Emirates.

The former Minister of Mining Ahmed Sadiq al-Karuri says that 75 percent of randomly produced gold goes into smuggling. In 2011, for instance, Sudan produced 73.4 tonnes of gold, equalling 3.1 billion dollars, and enabled the export of 30.4 tonnes, 41 percent of production, through official channels, which generated 1.4 billion dollars in revenues. In 2015, production volume reached 82.3 tonnes valued at 3.1 billion dollars, of which 19.4 tonnes, or 24 percent, were exported through official channels. Smuggling thus lost the public treasury revenues estimated at two billion and four hundred million dollars.

Unofficial mining exists in twelve of Sudan’s eighteen states, through 22 mining locations and 65 markets. It is believed that around 14 percent of the country’s population depend on unplanned mining in one way or another. Of the regions known for mining is the Jabal Amir region in North Darfur, where gold was found in 2012, once called “Switzerland”, controlled by the Rapid Support Forces and the incumbent deputy head of the military council lieutenant general Mohammad Hamdan Humeidati, who inherited the area from former militia leader Musa Hilal. In return for the fees he receives from the miners, numbered by the thousands, or through his share of gold sales, he protects them with his own militias. Some estimates note that the Jabal Amir mines generate around 54 million dollars at least to those who control it on a yearly basis. On the other hand, the revolting SPLM controls some mining locations in the Nuba and Blue Nile mountains; it makes use of them to fund some of its operations. At a time when domestic or unofficial mining contributes to nearly 10 percent of international production, its percentage in Sudan ranges between 85 and 90 percent of production.

Mining is considered an attractive industry to many impoverished rural populations, especially the workforce that hails from Darfur, Kordofan, and the Blue Nile. They are most drawn to this type of activity, as work opportunities are almost non-existent in their home regions and live in abject poverty. Due to such conditions, child and underage labour seems to be common in these areas. Likewise, the use of some chemical materials in the mining operations, like mercury, has negatively impacted the regions where they’re practiced and, more importantly, affected workers’ health – as mining is carried out in vacant lands, which lack the minimum of services, especially healthcare facilities.

Due to political instability and civil war in the country, both petrol and gold became the focal interest of many human rights groups, which saw that, by procuring further resources, the Salvation regime was perpetuating the war. As such, campaigns to put pressure on foreign companies engaged in the petrol domain in Sudan were launched to call for them to withdraw their business. As such, the Canadian company, Talisman, was forced to sell its own shares in the consortium that operated in Sudan to an Indian petrol and gas company, although it considered its own project in Sudan to be the best of its international projects.

The success that the Salvation regime saw in exporting petrol and receiving extra hard currency revenues was reflected as an improvement on its military abilities. This pushed the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington to write a report on Sudan, advising the revolting popular group to enter into serious talks to reach peace and split the petrol revenues rather than stop its operations. This would eventually be the basis of the diplomatic efforts that concluded with a peace agreement in 2005.

Likewise, a campaign was launched to freeze Khartoum’s gold sales, premised on the fact that its revenues were being used to finance the war in both the Blue Nile and South Kordofan. While such efforts did reach the United Nation, the Sudanese government was able to block those by resorting to its strong connections with Moscow.

As such, the state’s policies have exposed its rent-seeking approach, manifest in the decisions and measures it takes, and which have resulted in further unrest and political impasse. The latter endures, manifest in the ongoing popular uprising since December; it has been through much back-and-forth in its aim to achieve one of its most important slogans: a “civil rule”. It also places Sudanese nationals’ interests at the heart of the political process; it wishes to use the country’s resources for the people’s own good, with full transparency.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 04/07/2019