This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

On 150 square meters of land, Muhammad A. decided to build a house in the village of Nazlat Hanna, south of Bani Suef Governorate in central Egypt. He chose to purchase cement produced by Al-Arish factories, which were recently built in the governorate by the Egyptian army. He didn’t need to think twice before deciding to buy his rebar from the Egyptian Steel factory, which offered its product at the best price in the market. It is worth noting that the army now controls the Egyptian Steel Factory, which recently opened a branch in the governorate. For the marble, Muhammad chose the products offered by the Bani Suef complex for marble and granite, which produces 3.6 million meters annually since its opening last year, north of the governorate.

A short tour of the suppliers of building materials in the governorate can reveal the changes that the market has undergone since the army strongly entered the public sector in 2014. With their competitive advantages, namely their low prices, the materials produced by the military establishment’s factories have topped sales in all Egyptian governorates, revealing the growing economic influence of the army in Egypt. However, these sales uncover another invisible aspect, which is the degree of the massive expansion of the armed forces' grip on resources in Egypt, with a green light from the state and even laws designed for that purpose.

The State and the Army: Two Sides of the Same Coin

During the National Youth Conference in Aswan on 28 January 2017, President El-Sissi addressed the Egyptian people, saying: "We are very poor." The President had made similar statements only three years earlier, when he said: "I cannot give you anything. You do not need to ask me to give to you, because if I could, I would. Are you going to swallow Egypt whole or what?"

Egyptian officials have deliberately repeated the phrase “poverty of resources.” They have given this issue an air of mystery to stop citizens from asking the government to provide more services, improve conditions, or hold successive governments accountable. On the ground, however, the situation appears to be contradictory. Egypt has large quantities of various natural resources, such as natural gas, cement, iron, marble, and fisheries. But, no one knows how they are managed or how the people benefit from them.

In 2015, Egypt and the Italian company Eni announced, amid a great celebration, the discovery of the largest natural gas field in the Mediterranean, with a capacity of 30 trillion cubic feet. With other discoveries made east of the Delta, Egyptian officials boasted that it would transform Egypt from a gas importing country to a gas exporter. Although the actual production of this field began in early 2018, producing 2 billion feet per day since last September, gas and electricity bills have not decreased. On the contrary, prices have been soaring non-stop, which is part of the government policies put in place since 2014. These policies aim to convert fuel and other products, which were seen as services, into consumer goods that bring money to the national budget and finance the reform program agreed upon with the International Monetary Fund [IMF], as well as the controversial megaprojects that President El-Sissi is putting in motion. On 21 May 2019, the Egyptian Government announced a new increase in electricity prices by an average of 14.9 percent.

The huge gas production did not prevent the steady rise in the gas bill paid by citizens. Since 2014, government policies have aimed at converting fuel and other service products into consumer goods that bring money to the state budget and finance the reform program agreed upon with the IMF, as well as the controversial megaprojects that President El-Sissi is putting in motion.

On the other hand, it is unknown who the biggest beneficiary in the gas sector is, in light of the army's expansion in the sector through several companies affiliated with its National Service Projects Organization [NSPO], and its involvement in several international contracts. So the question is: Who manages the other resources? Is it the state or the army?

On 18 November 2018, President Abdelfattah El-Sissi inaugurated the Birkat Ghalyoun Fish Farm in the northern Delta, the largest fish farm in the Middle East. For 4 billion EGP [about $254 million], the project is built on 4,100 acres and will cover 13,000 acres when fully completed. Government officials presented it as an "integrated national project of which the Egyptians are proud," nearly doubling the fish farming production in Egypt and bringing the country closer to self-sufficiency.

However, this is not a national farm, as officials claim. The armed forces, which have founded the National Company for Fishery & Aquaculture in 2015, have established it. Like other productive agencies affiliated with the army, this company makes private investments, the returns of which do not enter the public budget. The expansion of the armed forces in fish farming moved with the support of President El-Sissi himself and with a legal methodology that allowed the army to not only dominate fish production in Egypt but weaken the competitiveness of government agencies and companies, which were the biggest players in this sector. Despite the government's slogans about developing fisheries, in the year the army established its fish farming company, the government reduced the budget of the General Authority for Fish Resources Development [GAFRD] from 128 million EGP [about $8 million] to 38 million EGP [about $2.5 million], instead of giving it the 438 million EGP [about $27.8 million] it wanted as part of its plan. This paralyzed the GAFRD, according to Muhammad Abdul-Baqi, the then chairman of the GAFRD, who added that the national fund to support the capabilities of the GAFRD (what he called "the magic key that helps the GAFRD carry out its work," had been abolished.

Within a year of establishing the Ghalyoun Farm, President El-Sissi issued a presidential decree imposing a new customs tariff of 5 percent on fresh and frozen fish, as well as other fish products such as those produced by the farm, to increase the competitiveness of domestic production. The state also banned fishing in the Red Sea, starting from February 2019, "due to security measures."

Governmental slogans promote the development of fisheries. However, in the year the army established its fish farming company, the government reduced the budget of the General Authority for Fish Resources Development (GARFD) from 128 million EGP to 38 million EGP, instead of giving it the 438 million EGP it needed for its plan. This led to paralyzing the GAFRD.

At a time when government outlets have partially stopped receiving fish produced by the GAFRD, local officials in the governorates were racing to provide outlets and vehicles to transport Ghalyoun Farm products and deliver them to citizens at prices 30 percent lower than the market price, in a strong blow to the principle of competitiveness.

Cement Between the Suits and the Khakis

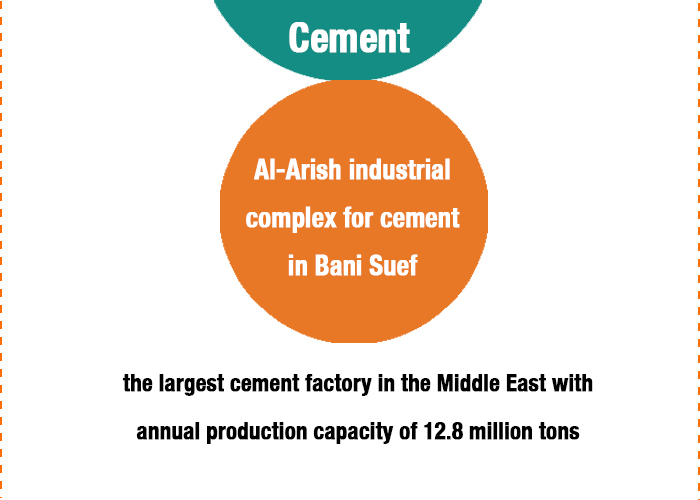

Less than nine months after the opening of the Ghalyoun Fish Farm, President El-Sissi inaugurated another "national" project amid media celebrations. Al-Arish cement complex in Bani Suef Governorate is the largest cement plant in the Middle East with a capacity of 12.8 million tons annually. Like the Ghalyoun Farm, this armed forces factory, with expenditures of $1.2 billion, has turned the cement production business upside down in Egypt.

In 2017, Egypt ranked ninth in the world in cement production at a rate of 69 million tons annually, according to the British Sigma Capital Corporation. Until the opening of this complex, the threads of this industry, which includes 29 factories in Egypt, remained in the hands of a private sector dominated by major European companies which comprise 70 percent of the business. This private sector rushed to buy these factories from the state, benefiting from the massive privatization campaign launched by former President Hosni Mubarak to sell the majority of public sector companies at the beginning of 1995, though that campaign had been marred by numerous accusations of corruption. During the privatization era, Italy's Italcementi took control of three major cement companies, namely Asec Cement, Tourah Cement, and the government's 55 percent stake in Suez Cement, before selling it to the German company Heidelberg. The Mexican company Cemex purchased the Asyut Cement Company, and the French company Vicat acquired 30% of the shares of Sinai Cement. Between 1998 and 2000, the Portuguese company Cimpor-Cimentos acquired the Al-Amiriyah Cement Company during a public offering on the stock exchange. The French company Lafarge and the Greek Titan also bought Alexandria Cement and Bani Suef Cement.

Al-Arish cement complex was recently established as the largest cement plant in the Middle East, with a capacity of 12.8 million tons annually and expenditures amounting to $1.2 billion. Affiliated with the Armed Forces, the complex has turned the cement production equation upside down. Three months before its opening, one of the only two governmental companies in this sector shut down, and more than 2,300 workers were laid off due to the lack of funding.

Ironically enough, the national cement industry was turning its final page with the closure of one of the two remaining governmental companies in this sector. This happened barely three months before the official opening of the Al-Arish cement complex, and more than 2,300 workers were laid off due to the lack of funding to modernize the company. During a public meeting on 17 May 2018, the board of directors of the National Cement Company, whose shares are mostly owned by the state, announced the closure of the company due to losses.

According to the company’s annual production report, National Cement was producing 4.5 million tons of cement annually through its four affiliated factories until 2014. But since 2015, the company has been closing its factories one after the other and falling into a viscous cycle of losses. The company’s management justified the losses with the development process imposed by the government to switch from using natural gas to coal in production furnaces. This is in addition to the absence of factory development and maintenance, the rise in the prices of raw materials, and the liberalization of the exchange rate. In 2016, the company's losses amounted to 119.5 million EGP [about $7.5 million]. Hence, its management decided to cut losses by closing all factories. But losses continued to rise suspiciously, reaching more than 971 million EGP [about $61.7 million] in 2017, according to former Minister of Manpower Hisham Tawfiq.

However, a report by the Central Auditing Agency, one of the independent bodies responsible for monitoring the activity of institutions in Egypt, noted that a large part of the losses was intentionally inflicted in order to lead to the company’s liquidation. The report said: "The losses incurred by the company in 2017, which amounted to 971.3 million EGP [about $61.6 million], were due to its management's decision to cease production. In 2016, when two factories were partially operating, the losses did not exceed 119.9 million EGP [about $7.6 million]." The report explicitly accused the management of obstructing production and halting work, which exacerbated the repercussions of high fuel prices and the exploitation of quarries.

However, the closure decision did not appeal to the businessmen who own a 4.5 percent stake in this huge company. During that board meeting, a businessman accused the company's management of colluding with the scheme to allow the army to control the cement market. With the closure of the National Cement Company, the state no longer owns any part of its cement industrial empire, except for the Nahda Cement Company in Qena, which is currently managed by a Major General.

At the end of February 2018, the army also opened two new factories belonging to its complex in Al-Arish, North Sinai, raising its production from 3.2 million tons annually in 2011 to 9.6 million tons last year. This huge productivity is supported by an important factor - the unpaid labor of conscripts - and the army's control over all crude cement quarries in Egypt, which raised their prices threefold. It should be noted that the army has started managing these quarries under a decree issued by President El-Sissi in 2014.

On 16 May 2019, the management of the Suez Cement Company [SCC] announced a temporary suspension of the production of Tourah Portland Cement Company, which the SCC owns 66.12 percent of its shares, justifying this by the deterioration of its financial returns and losses during the first quarter of 2019, with net losses exceeding 95 million EGP [about $6 million].

Rebar from Political Business to Military Uniforms

The iron industry is one of the important indicators of the shift in power centers in Egypt during the last three decades. The business elite, who had emerged in the final years of late President Anwar al-Sadat’s presidential term, was able to tighten its grip during the Mubarak era due to the political support it enjoyed for its affiliation with the ruling party or thanks to the massive loans from government banks that contributed to creating wealth from scratch. Since the first day of implementing the government privatization program in the 1990s, this elite focused its attention on controlling this industry and removing the state's grip.

The political and financial rise of businessman Ahmad Ezz is a clear example of finishing off the national industry in ways that bear suspicions of corruption and intentional sabotage, dominating the country's natural resources through a class of businessmen who are part of this political system. Ahmad Ezz, who once ran a small scrap shop in the Al-Sabtiyah neighborhood of Cairo, became the unrivaled iron emperor in Egypt by the beginning of the third millennium and the decision-maker who dominated the policies associated with the iron industry. He benefited from the support of Jamal Mubarak, the son of late President Mubarak, and relied on the torrent of loans he had obtained. This is in addition to the corruption deals that allowed the expansion of this empire at the expense of the government-industry, especially the Al-Dukhaylah Company (formerly Alex Company for Steel and Iron).

In a report published on 25 November 2011, Al-Ahram newspaper said that Ezz managed to set his foot in the state-owned Al-Dukhaylah Company through an illegal agreement, by which he acquired 28 percent of the shares of this state-owned company in February 2000. This allowed Ezz to become the chair of the company’s board. One month later, Ezz made the peculiar call to reduce the production of Al-Dukhaylah from 1.5 million tons annually to one million only to raise the production of his factory, Ezz Steel Rebars, in Sadat City. Ezz also monopolized the raw materials used to produce iron in Al-Dukhaylah and transferred them to his factory at prices below market value. All this was accompanied by government policies which made way for the voracious businessman to monopolize the industry, as the government imposed a 61 percent customs duty on imported iron. In 2006, Ahmad Ezz made a stock exchange between his factory and Al-Dukhaylah, which enabled him to own 52 percent of the Al-Dukhaylah, thus earning the title of Egypt’s “iron man”.

Ahmad Ezz, who once ran a small scrap shop in the Al-Sabtiyah neighborhood of Cairo, became the unrivaled iron emperor in Egypt by the beginning of the third millennium, dominating over the policies associated with this industry. He benefited from the support of Jamal Mubarak, the son of late President Mubarak, and from the torrent of loans he had obtained through corruption.

The decree to impose new protective tariffs on iron imports serves its major manufacturers, but it constitutes a severe blow to about 22 small factories working in the field of iron and rolling. The chairman of the Metallurgical Chamber at the Federation of Egyptian Industries warned that this decree would lead to the closure of 22 factories and the layoff of about 25,000 workers.

After the 2011 revolution and with the fall of Mubarak’s, Ezz was forced, under political pressure and settlement processes with the government, to abandon Al-Dukhaylah Company. Since then, the policies that control the threads of this industry, which produced 11.5 million tons annually until 2017, have begun to move unsteadily. However, with President El-Sissi assuming office in 2014, the iron industry was placed at the army’s fingertips through the National Service Projects Organization [NSPO].

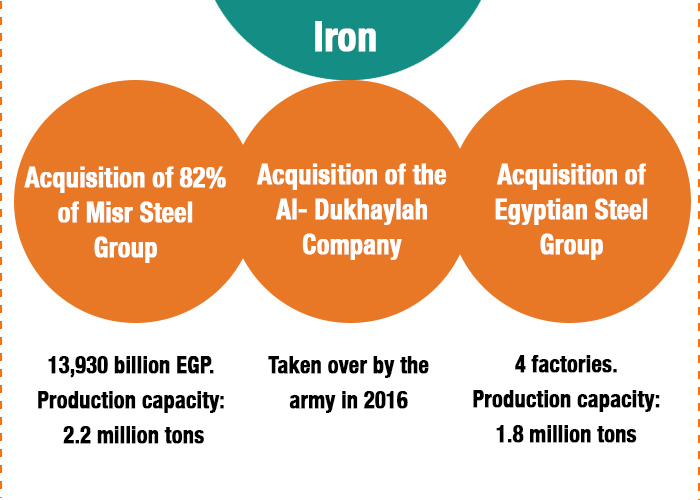

A short tour of the website of the NSPO, a military-affiliated agency, reveals the shift in the iron monopoly forces in Egypt, in comparison to the years pre-2011. In a deal worth 13.930 billion EGP [about $889 million], signed in November 2016, the NSPO acquired 82 percent of the shares of Misr Steel Group, owned by businessman Jamal al-Jarhi and another Lebanese businessman, with a capacity of 2.2 million tons. The NSPO also acquired the Egyptian Steel Group, which includes four factories with a total production capacity of 1.8 million tons. As for the Al-Dukhaylah Company, which sparked controversy before the January revolution, it was handed over in 2016 to the army for development. Meanwhile, Ezz stayed in his factory (Ezz Steel Rebars) with a production capacity of 3.8 million tons.

In the last third of last April, businessmen launched a secret campaign in mass media to condemn a new decree issued to impose, for six months, a 25 percent protective tariff on imports of rebar and steel and a 15 percent protective tariff on crude iron. The decree was issued under the pretext of "protecting national industries from unfair competition with foreign products." It is worth noting that this campaign was halted under "sovereign" pressure, according to a press source who participated in the campaign. This decree was issued more than a year after Egypt imposed anti-dumping duties on imports of rebar. However, this decree, which serves major iron manufacturers in Egypt, especially Misr Steel, Egyptian Steel, and Ezz Steel Rebars, will constitute a severe blow to about 22 small factories working in the field of iron and rolling. Businessman Jamal al-Jarhi, chairman of the Metallurgical Chamber at the Federation of Egyptian Industries [FEI], who currently owns the Suez Steel Factory, warned that this decree would lead to the closure of 22 factories and the layoff of about 25,000 workers.

The Booming Marble Sector Catches the Army’s Eye

The marble and granite industry is another leading sector in Egypt that has caught the attention of the armed forces. It all started in 2014 when President El-Sissi issued a decree transferring the right to operate marble and granite quarries from the police and municipalities to the army.

On the day following this decree, the army doubled the tariff for quarrying factories and workshops operating in this sector, not to mention the increase in prices several times during the following years. The owner of a marble factory in the Shaqq al-Thuban industrial area, which produces 80 percent of marble and granite in Egypt, told the researcher that the prices of quarrying rose three months earlier from 50,000 EGP [about $3,174] to 250,000 EGP [about $15,877].

On 30 April 2017, members of the Marble and Granite Chamber at the FEI were taken aback when a Major General dropped by during their weekly meeting. The Major General told them that the army was planning to build a large marble-manufacturing complex, and asked businessmen to provide it with the necessary expertise. Businessmen protested against this step, stressing that their industry is in decline due to the situation in Libya and the Gulf, the largest markets that receive Egyptian marble exports, and the Chinese invasion of this industry, as well as the exaggerated rise in electricity and gas prices for factories and workshops. Two years have passed since that meeting, and instead of the one complex that the army wanted to build, four have been built near the quarries that it manages: The Zaafarana complex in the Red Sea Governorate, the Marble City complex in Al-Jalalah in the same governorate, the North Sinai complex, and the Bani Suef complex for marble and granite.

The marble and granite industry is another leading sector in Egypt that has caught the attention of the armed forces. It all started in 2014 when President El-Sissi issued a decree transferring the right to operate marble and granite quarries from the police and municipalities to the armed forces.

During the inauguration of the cement factory in Bani Suef in mid-August 2018, President El-Sissi's schedule included the inauguration of another huge project - the Bani Suef complex for marble and granite, which includes five marble and two granite factories with a production capacity of 3.6 million square meters annually. During this visit, President El-Sissi stressed that there was a plan to build complexes close to all quarries in Egypt, whether in Sinai, Al-Ayn Al-Sukhnah, or Aswan.

Four months after the opening of this complex, President El-Sissi, accompanied by army major generals, inspected another huge complex - the first three factories in the Jalala city for marble and granite in the Red Sea Governorate. This complex is supposed to include eight marble factories with a total capacity of 24 million square meters, a granite factory with a capacity of one million square meters annually, and three factories for production requirements. With this productivity, the army’s total production from these two complexes amounts to 28.6 million square meters annually. It is approximately equivalent to the total production of Egypt’s civil factories, which is 30 million square meters, per the latest statistics in 2016. It should be noted that the total production of Egypt’s civil factories was 40 million square meters in 2014, according to engineer Ibrahim Ghali, chairman of the Marble and Granite Division at the FEI.

The President completed his visit by inspecting the complex of compound phosphate fertilizers in Al-Ayn Al-Sukhnah, which was established by the Nasr Company for Intermediate Chemicals – a company affiliated with the NSPO. The complex includes nine factories for the production of fertilizers, with a capacity of about one million tons per year. Meanwhile, the total production of fertilizers in Egypt is 15.5 million tons per year.

In parallel, the problems of factory owners aggravated. For instance, the government refused to grant legal status to factories in the Shaqq al-Thuban area, which caused the closure of some factories; imposed restrictions on these factories' use of the Nile water; and postponed the issuance of export approvals without a convincing reason, amid rumors that preparations are being made to transfer this industry from this leading area to a far place. Speaking on condition of anonymity to avoid harassment, the owner of the aforementioned marble factory, who is also a member of the Chamber of Commerce, said that the exports of his factory and the area had fallen by one-half since last year.

Moreover, the Black Sand Company, which the NSPO owns most of its shares since its inception in 2016, is also working on establishing two factories with an area of 80 acres and 35 acres, respectively, to exploit the black sands scattered on the coasts of the Mediterranean to extract minerals.

From an Anti-Monopolist to the Sole Monopolist

From the very first moment, the army realized that its huge production of cement, marble, and iron will not remain in its stores because of its monopoly on implementing and supplying the huge national projects launched by President El-Sissi, especially the administrative capital, whose area is intended to reach 12 times the size of the US city of Manhattan. Moreover, the army offers its product at prices lower than the market prices, benefiting from customs and tax exemptions on its products and from cheap labor that depends on conscripts. This is in addition to the huge facilities provided by the various ministries that grant the army the implementation of projects by direct order.

The military not only wants to prevent any monopolistic practices by the private sector, as officially declared, but to become the sole monopolist of these resources.

The owner of the aforementioned marble factory said that the army has entered the economic sectors armed with its vast influence; it has moved above every law of the market, benefiting from huge privileges that make its competitors seem like cats wrestling with a lion. But what is the reason behind the big ambitions of the army to control the natural resources in Egypt? Is it to create balances in the market, especially in the cement and iron sectors, and prevent any monopolistic practices in these sectors, according to President El-Sissi’s statements on the sidelines of the youth conference at the end of October 2016? The bigger picture reveals another aspect. The military not only wants to prevent any monopolistic practices by the private sector, but to become the sole monopolist of these resources.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 06/06/2019