" This file was produced as part of the activities of the Independent Media Network on the Arab World. This regional cooperation brings together Maghreb Emergent, Assafir Al-Arabi, Mada Masr, Babelmed, Mashallah News, Nawaat, 7iber and Orient XXI."

In August 2014, hundreds of cultural practitioners and members of the public gathered around a large wooden stage, set in the garden of the Abdeen Presidential Palace in the heart of Cairo. In this open space, some banners were held up in support of Gaza, while others demanded the release of detainees from Cairo's prisons. The audience realized that this was the last time the authorities would allow the street art festival, El-Fan Medan[1], to be held. According to musician, cultural activist, and one of the festival's co-founders, Ayman Helmy, "El Fan Medan is one of the gains of the revolution and a remarkable victory in one of its key battles: the battle for public space”.

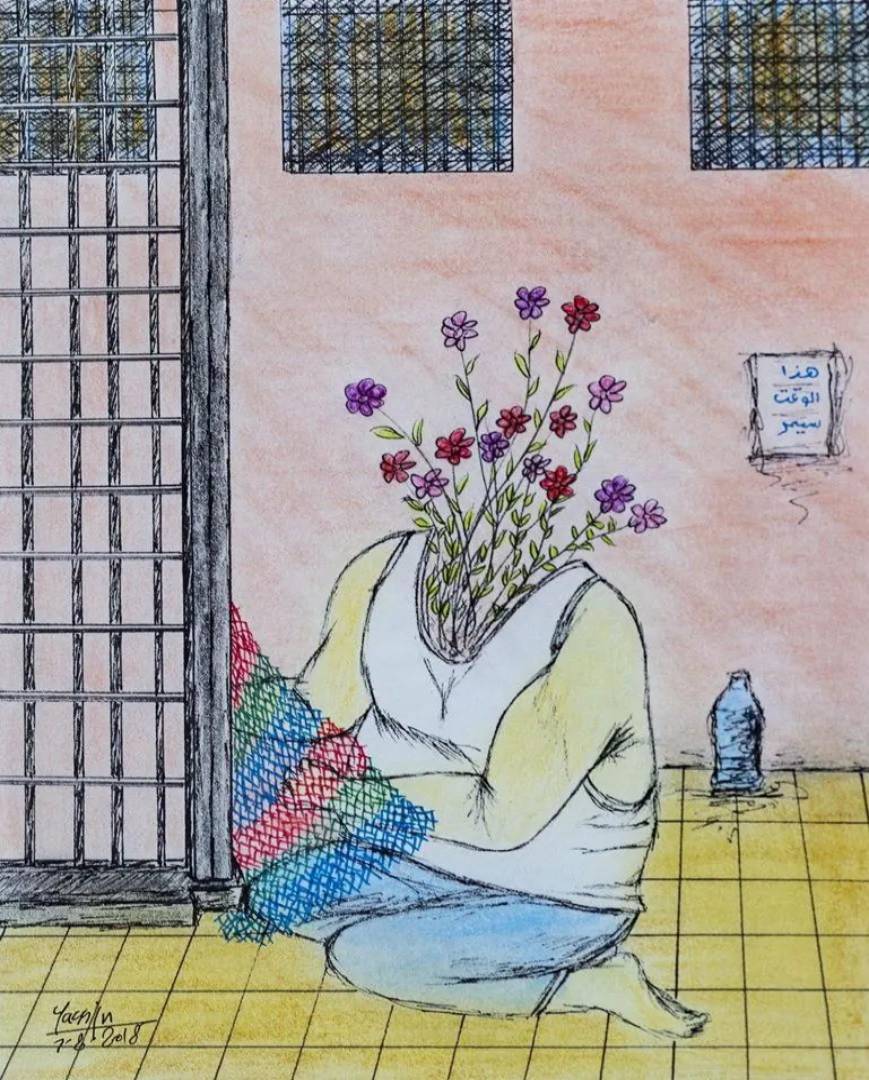

The 25 January 2011 revolution bolstered various forms of art, notably graffiti, which was prominently displayed on Mohamed Mahmoud Street near Tahrir Square[2]. However, this open space soon became obsolete, after the executive regulations of the new Protest Law were issued in 2014, curtailing the street's status as a free public arena for artistic and cultural expression.

Interview with Ayman Helmy

President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi rose to power in 2014 with an electoral platform that promised the protection of culture and the preservation of heritage and antiquities. However, what followed was a stark violation of Egypt’s Constitution and its established fundamental principles protecting culture, the freedom of creativity, and the right to the exchange of information. Those spaces were diminished to an unprecedented extent, as arresting people from merely expressing themselves became commonplace. Since 2016, the cultural scene in Egypt has been subjected to a series of repressive government decisions. Libraries and cultural venues across Cairo were shut down, books were confiscated, and writers and publishers were routinely arrested. Among those were two branches of the Karama Bookstores chain and Al-Balad Bookstore, which was shut down under the pretext of lacking proper licensing.

The third quarter of 2024 saw increased crackdowns on the freedom of expression. Cartoonist Ashraf Omar was arrested, and films such as Hani and Tarot were banned, citing religious and political reasons. The head of the Musicians Syndicate also banned Mahraganat[3] performer Hassan Shakoush from performing, referring him to investigation over a video he posted criticizing his mistreatment at Tunis Airport. Meanwhile, the Actors Syndicate issued a restrictive decision banning bloggers from taking acting parts in any local productions.

In spite of all this, there were sustained attempts to confront these policies, and cultural productions continued to emerge under a regime that persecuted creativity and creators.

Has oppression succeeded in stifling expression?

Complex mechanisms of domination and oppression, which permeated systems of social, political, and cultural authority, were described in a report by Amnesty International as being “ruthless in clamping down on any remaining political, social or even cultural independent spaces (…) more extreme than anything seen in former President Hosni Mubarak’s repressive 30-year rule." But despite it all, Egyptians were able — even if only partially and often stealthily — to confront these restrictions through their deeply rooted sense of creativity. Popular proverbs, for example, have always been and continue to be used as a weapon against injustice and a profound provocation for self-criticism and social critique. Expressions like "Even the longest night sees the crack of dawn” become metaphors for resistance, while proverbs such as "He who protects it is he who steals it" offer a sharp criticism of corrupt authorities.

“The Egyptian is born with a papyrus in his heart, written on it in gold letters: sarcasm is the savior from despair”, French novelist of Egyptian origin, Gilbert Sinoué[4], once said. Despite what can be described as regression or oppression, the daily practices of the people have succeeded in sounding their clear presence. Comics — whether shared on social media or displayed in the streets — are one example, rising in prominence following the decline of the newspaper caricature, due to the clampdown on free press. For instance, in the 2024 Faisal Street Screen incident, a protesting artist hacked an ads screen to display a message of political irony, via an illustration depicting al-Sisi dressed as a masked thief, with the phrase "Did you not know that I am a thief?" written below it.

Independent cinema in Egypt has been one of the fast-growing creative endeavors over the last decade. Despite the many obstacles it faces, it has become a refuge for artists who seek a free expression space in the public sphere. An example that stands out in this regard is the documentary film The Brink of Dreams[5], which won the 2024 Cannes Film Festival's Golden Eye Award. The film was made by a group of young independent female artists in Minya Governorate, who founded a theater troupe and presented street performances, inspired by the plight of marginalized women in Upper Egypt.

In addition, Egyptians began creating alternatives for suppressed cultural expressions, with new initiatives emerging from intellectuals who deliberately avoided direct confrontation with political and economic authorities, opting for the less "revolutionary” (or the less "radical") route in order to survive. Among these was the Rasm Misr (Draw Egypt) initiative, which aimed to document archaeological and heritage sites through illustrations, before their already-underway demolition. Similarly, the Cairo Biography initiative sought to preserve Cairo’s heritage and raise awareness of its history.

New cultural productions that spoke to Egypt's impoverished and marginalized communities started to emerge outside of the capital's centrality. Away from the monitoring and monopoly of state-sanctioned media, individuals and families from various governorates used social media to produce alternative dramas that addressed their social and economic hardships, which became dubbed Al-Hamesh Television (meaning “The Margin’s Television”). By sharing content that was based on their own regional cultures, these creators used their platforms to subtly protest the United Media Company's monopoly, as many believed its productions no longer represented them.

With the obvious growth of the audience for this kind of content, the authorities took notice and swiftly started enforcing regulations, such as taxing the income of content creators, starting in September 2021, or arresting others on charges of foreign currency trading, in an attempt to confiscate their dollar savings, as in the case of content creator Ahmed Abu Zeid.

From Inside Prison

As the number of prisons and detention centers in Egypt increased, many detainees imprisoned for their political views or opinions found creative ways to voice their suffering from behind bars, and prison literature was their refuge. Among the most prominent writers of the genre is political activist and journalist Ahmed Douma, who spent nearly a decade in prison. During his incarceration, Douma managed to smuggle out his first poetry collection, Curly, using ingenious methods.

Poetry and Pestilence

05-04-2016

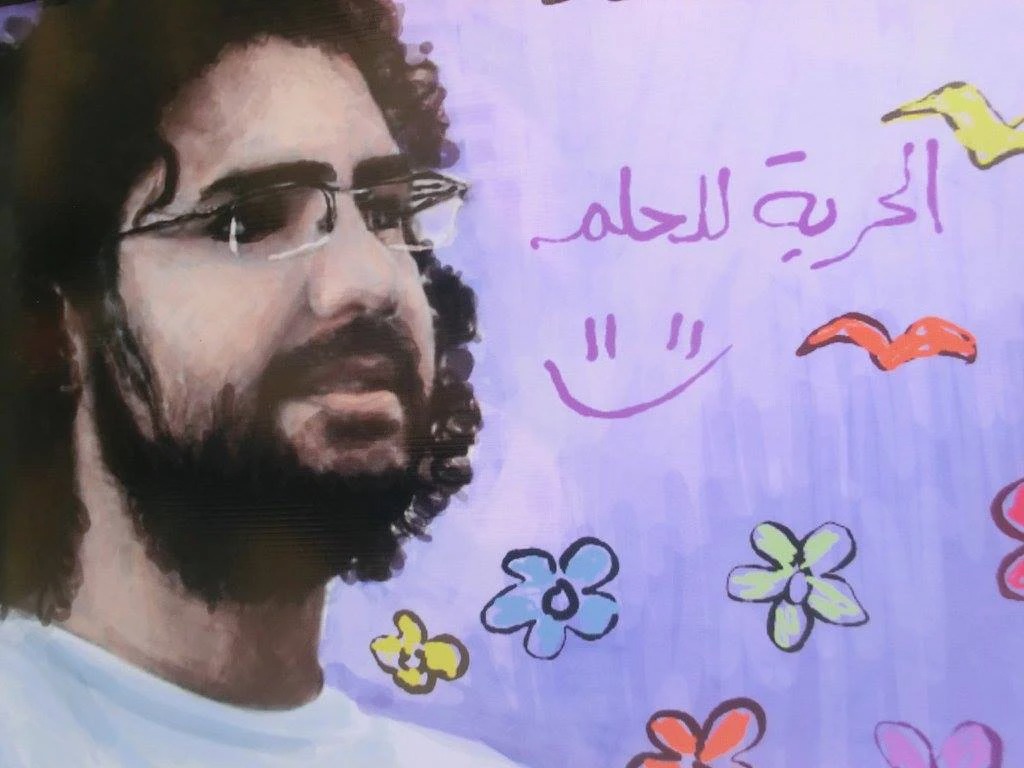

Another notable writer is political activist and journalist Khaled Daoud, who, after his release, published a series of literary articles reflecting on his years of suffering in prison. Alaa Abdel Fattah’s You Have Not Yet Been Defeated has also stood out as a seminal work of prison literature. Meanwhile, Alaa remains jailed, as the Egyptian regime continues to resist all calls for his release. In an exclusive interview with Assafir Al-Arabi, Amhed Douma recalls that the authorities had promised him and Alaa that they would “remain in prison until they either die or go mad”.

As part of this research, we have conducted interviews with both Khaled Daoud and Ahmed Douma to discuss their prison literary productions and the crucial role of documenting history from within the prison walls.

The Unpublished Prison Diaries

Khaled Daoud recounts the reasons that led to his 19-month imprisonment, which began in September 2019, after the Egyptian regime grew unsettled by the calls for protest made by building contractor Mohamed Ali. The public calls sparked widespread demonstrations across the country, and as a result, thousands of citizens and public figures, including Daoud, were arrested. He believes that his writings, which were critical of the regime, particularly provoked the authorities. In his opinion, the broader crackdown on writers and activists is closely linked to the controversial agreement signed in April 2016 between Cairo and Riyadh, which ceded sovereignty of the Tiran and Sanafir islands. Public opposition to the deal led to a surge in protests, and thus to more arrests. By 2019, the year of Daoud’s arrest, the intensity of state repression had reached a new peak.

Interview with Khaled Daoud

Daoud describes his experience of prison, which inspired him to write a diary later compiled into a book titled Pre-trial Detainee. The book did not find its way to getting published due to the restrictions imposed on Daoud. He explains that political and cultural detainees faced particularly severe restrictions—including limited access to daily yard time and even to basic personal hygiene products. Books became Daoud’s only companion, especially novels and the few history books that were allowed. Newspapers, however, were tightly controlled. Daoud could only receive these three days after their publication, and they were limited to government papers.

"I discussed the book’s classification with my publisher, and he told me that it is part of the prison literature genre," Daoud notes. Hence, he approached the diary with a journalist’s eye- documenting the hidden realities of life behind bars in the context of the broader political landscape outside. His writings became a window into the closed off world of life in prison, offering a detailed guide to the daily realities faced by those held in Egypt’s pretrial detention system.

The diaries also recount the immense difficulties endured by prisoners in their efforts to write to their families. Even acquiring a pen and a few sheets of paper required prior approval from National Security. When letters to family members abroad were finally permitted, they were first read by an officer, censured, and returned to be re-written with the selected approved content, before they were finally sent.

A month after his release, Daoud decided to expedite his writing process and began publishing excerpts from his diary in a series of 22 articles on the Al-Manassa news website. He planned to compile the articles into a book—but the process was abruptly halted after his publisher received a warning from a National Security officer not to proceed with printing, despite the fact that the book was already registered, with an official identifying number.

When asked about the broader issue of state repression and its impact on creativity, Daoud reflects on the dramatic distance between the post-2011 period—when Egypt briefly experienced unprecedented cultural openness—and the expansive repression in the years that followed. He describes the current climate as “suffocating”.

“Like a chant... Like a whimper”

Much like Alaa Abdel Fattah, Ahmed Douma was one of the 25 January Revolution’s icons. He spent ten years in prison, including seven and a half years in solitary confinement, until his release in August 2023, by presidential pardon. During his lengthy years of imprisonment, and since his very first night in a cell, Douma devoted himself to writing and documenting. He describes writing as his way of escaping the harsh conditions of prison and resisting the authorities’ 'mission' to drive him insane. In his first poetry collection, Your Voice Is Heard, published in 2012, he shared his revolutionary poems about the times in which he joined protest movements prior to the 25 January Revolution, when he took part in the Kifaya and April 6 movements. The poems annotated with the dates during his imprisonment and the places of his detention.

“I completed seven books over the course of ten years, including poetry in colloquial and classical Arabic, a collection of short stories, and a collection of articles, in addition to a novel in-the-making. Writing was not only my way of coping—with myself and with life – but also my source of income,” Douma says. “During prolonged detention and solitary confinement, a person might start to lose control of his mind and thoughts, so writing was my means of survival. I focused on it as a way to document and claim the narrative with honesty and non-defeatism,” he continues.

Interview with Ahmed Douma

People often wonder how detainees manage to smuggle their cultural and journalistic works to the world outside, considering the conditions of strict control over the scarce visits allowed to family members or lawyers—each preceded by a thorough physical inspection. Douma had to devise numerous methods to smuggle out his writings, including writing on underwear and scribbling on tiny scraps of paper. He later used a basic mobile phone he had managed to obtain, on which he would record his poems and send them out in brief text messages. He would even carve messages with his fingernails into the walls of his cell.

“There are dozens of methods I might share one day,” he says, “but they’re still in use inside prisons, and revealing them could jeopardize their users[6].” He recounts how he even learned some smuggling techniques from criminal inmates—particularly drug dealers, but Douma sarcastically remarks, “Smuggling drugs is easier than smuggling a poem or article out of prison.”

Douma kept the scraps of paper and makeshift tools that had accompanied him in his cell for years, as reminders of his experience. Among them were dozens of poems he could not yet publish, due to restrictions placed on him and on any publisher willing to help. He recalls how, during the first ten months of his detention, one of the jailers burned everything he had written. Douma, nevertheless, remained resolute and continued to smuggle out every one of his pieces of writing.

Of the seven works Douma produced while in prison, only two have been published: Curly, a poetry collection (2021), and the book Like a Chant... Like a Whimper (2022). The latter, a compilation of poetic prose texts, is what Douma considers the pinnacle of his prison literature, encapsulating the essence of his experience. When plans for publication failed, the project—which had begun as a series of articles for a newspaper meant to earn him some income while incarcerated—finally turned into a book. He wrote a collection of short stories in 2016, and he is now looking for a publisher for his next book, A Hope Too Heavy for Roses, an ongoing text he has been working on since 2021.

Douma reflects on how scenes of Syria’s Sednaya Prison stirred painful memories of his own detention, inspiring him to begin documenting everything he had witnessed in Egyptian prisons, as well as similar experiences from around the world. His new project, titled A Hand-Span and a Fist, will include short written pieces and a video series currently in production. Douma hopes the authorities will end their crackdown on poetry and literature, so he can finally publish freely. He has hopes that his voice, now outside prison walls, will no longer be confined to the genre of prison literature alone.

______________________

Translated to English by Sabah Jalloul

- “El Fan Medan” is Arabic for “Art is a [Public] Square”. ↑

- From the outset of the 2011 revolution, Graffiti has played an inspiring role as a vital tool of popular protest. Artists have chronicled the various stages of the revolution on the walls of streets, the most famous of which was Mohamed Mahmoud Street near Tahrir Square, where dozens of murals were painted, featuring martyrs and documenting the events from the first days of the revolution until the Muslim Brotherhood’s rise to power. The regime then decided to erase all the murals, claiming that this was necessary for underway renovations at the American University in Cairo (AUC), which occupies a large part of Mohamed Mahmoud Street. The graffiti that once featured on the AUC’s front fences have been documented. ↑

- Mahraganat is a genre of popular Egyptian songs that combine elements of Shaa’bi music (traditional Egyptian folk music) with electronic dance music, reggaeton, grime, and rap. ↑

- Born in Cairo in 1947, Gilbert Sinoué's birth name was Samir Gilbert Kassab. ↑

- Original title: “Rafa’at Einy ll Sama” (I Raised my Eyes to Heavens). ↑

- Suha Bechara, a Lebanese resistance icon who attempted to assassinate the Israel collaborator, General Antoine Lahad, and who was herself detained in the Khiam torture prison in southern Lebanon for ten years (including six years in solitary confinement), had decided to gift her book, “I Dream of a Cell of Cherries,” (published by Dar Al-Saqi in Beirut), to these detainees in Egypt. In her book, she describes her methods of writing and smuggling writings from prison. ↑