Published by: Alternative Policy Solutions

4 march 2024

Egypt signed the biggest direct investment deal in its history, giving ADQ, an Emirati sovereign fund, the right to develop 170 million m2 of the best beaches on the North Coast, located in Ras al-Hikma. While officials celebrated the investment, hoping it would pull Egypt out of its economic slump, Egyptians have been cut out of the loop, given no information about the project details, the price of the land, the specifics of the Emiratis’ 65% share of the project returns, or how affected landowners will be compensated.

The Ras al-Hikma deal exemplifies two features that have characterized privatization deals in Egypt since 2022: Gulf states’ acquisition of premium assets—assets of unique historical value or prized location, or profitable, promising companies—and the lack of transparency and regulation.

The shift from aid to investment

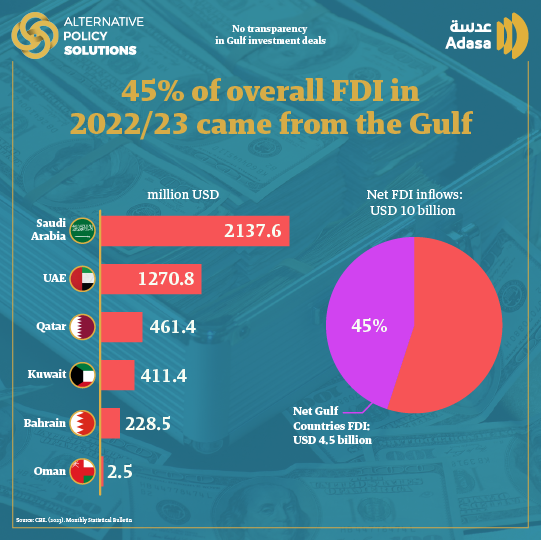

The Russia-Ukraine war and the Covid-19 pandemic compounded the fragility of Egypt’s debt-laden, inflation-ridden, mismanaged economy, prompting the government to seek assistance from Gulf states. But after giving Egypt more than an estimated USD100 billion in various forms of aid from 2013 to 2022, Gulf governments began to criticize the Egyptian government’s utilization of those funds and decided to abandon unconditional support and lean into for-profit investments.

Is It a Fair Deal?

The lack of detailed info about the deal, in addition to the negative track record of similar projects, raises a lot of questions about the fairness of the deal in terms of value as well as its environmental and social consequences.

Selling Egypt's Assets: Who Has Ownership?

14-06-2022

The UAE has been awarded contracts to manage the ports of Ain Sokhna and Safaga, while Saudi and Emirati sovereign funds acquired a 52% share in Alexandria Container and Cargo Handling. The firm controls activity in the port of Alexandria, the transit point for 60% of Egypt’s foreign trade. The Egyptian government brought in EGP6 billion on the deal, a modest sum given that the company’s profits in 2022/23 came to EGP4 billion. Qatar is currently seeking to acquire the ports of Damietta and Port Said. If the deal goes through, the most important Egyptian ports would all be under Gulf management.

Egypt sold 41.3% of Abu Qir Fertilizers—the second largest company listed on the Egyptian stock exchange and the largest fertilizer producer in the country—to Saudi and Emirati sovereign funds for EGP14 billion, which is equivalent to the firm’s annual profits in the fiscal year ending in June 2023.

The Gulf funds also own a 45% stake in Misr Fertilizers Production Company, which together with Abu Qir was included in Forbes’ list of the 50 best companies operating in the Egyptian market. Both firms receive subsidized gas, a measure originally approved by the government to reduce agricultural costs for farmers but which will now subsidize the profits of Gulf sovereign funds.

Additionally, the government sold a 39% share (subsequently increased to 51%) in the holding company that owns seven historic hotels for USD800 million to the Talaat Moustafa Group’s Icon and a “foreign” partner whose identity was not disclosed at the time. A 40.5% stake in Icon was then sold to Abu Dhabi Investment Fund and ADNEC, in January 2024. While the budgets of these hotels are not made public, they are strong competitors with the private sector due to their outstanding locations and historical value, as well as the fact that they are managed by international firms. The hotel deal raised questions about the legality of selling buildings that are more than a century old. The sale came a few months after the minister of the public business sector confirmed that these historic hotels were not on the block because it was too difficult to appraise them. As the minister remarked, “They are invaluable.”

Most of those deals were concluded absent a competitive bidding process, and the criteria involved in choosing between a public offering or sale to a strategic investor have not been made public. Nor has the public been informed of how the companies’ shares have been valued in cases of public offerings on the stock exchange, making it difficult to assess the fairness of the deals. And, of course, no agreement has been put to parliament, and MPs have not taken the initiative to submit formal briefing requests about any agreement.

Transparency and accountability are a necessity, not a luxury

Although the state celebrated the Ras al-Hikma deal and its impact on alleviating the dollar crunch, it did not announce how it planned to spend the first tranche of the deal (USD15 billion). The dollar gap is currently estimated at USD25 billion until 2028, while total external debt stands at USD164 billion. Nor did officials explain how the returns on this project would differ from the anticipated yield on investments pumped into al-Alamein which came at EGP185 billion. Finally, no state party has clarified the environmental impacts of the Ras al-Hikma. This question is no longer a luxury that concerns only visitors to the North Coast, it is related to the erosion of the entire Egyptian coastline with its consequences on the lives of Egyptians.