This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

"No pain, no gain"; “He who wants the honey must endure the bee stings”. These are some of the proverbs I have heard Samra and Sabrine (1) say. They sum up the day-to-day life of daily wage earners who work in informal (2), unregulated, or precarious economies; all of which are various names of one phenomenon where the situation is almost always the same. No stable job, no health care or social security, no paid vacations, no retirement, no end-of-service gratuity, and a work environment unsuitable for women.

In the case of female street vendors (3), not only do they face difficulties working on the street they also encounter harassment from the owners of the shops in front of which they sell their products. These shop owners impose a daily or monthly fee that the vendors have to pay, while the latters are also chased away by the police for operating “without permits” (4). “Oh dear, they really hurt me financially,” said one of the street vendors, “They confiscate one, maybe two thousand pounds worth of merchandise, and when I go to pick it up, I always find that they have kept the best of my goods for themselves and left me the low-quality stuff.”

Some of the women I spoke with, whether originally from rural or urban areas, have been able to improve their economic situation, while some are barely making enough to meet the needs of their families and have to resort to handouts, or receive regular aid from the government (5). Usually, they bear the financial responsibility in their families, or at least the larger portion of it, due to a husband's illness and his inability to work, his insufficient salary, or because of divorce. These women’s ages range between forty and sixty, and they are usually illiterate of a meagre educational level (6).

Sabrine: The vegetable seller

Every morning, Sabrine carries big sacks of vegetables on top of her head. The worker in the delivery truck parked on the market’s main street places one sac after another for her to carry to where she sets up her stall in a spot not too far down the street. However, the heavy sacks make the distance feel much longer.

When Sabrine was a child, she used to come to the market with her mother, who was the breadwinner in her family since Sabrine’s father was an elderly man. She quickly learned the trade and started selling and earning money, and after her mother’s passing, Sabrine, barely twelve years old then, took her place. "I was really young, but I was vigilant. No one could take advantage of me because I started going to the market really young." Sabrine says that she has been helping support her family ever since she was 9 years old, "every day I used to place 20 Egyptian pounds in my father’s hand" to spend on the large household that included many children. She also single-handedly paid for hers and her sister’s marriage trousseau.

Sabrine got married at twenty and stopped working in the market for ten years. At the time, she was living in a multi-generational household with her extended family. To repay a loan and build a separate house on her husband's share of his father's land (which was distributed to his male children during his lifetime), she decided to go back to working in the market, but this time with her husband. However, he soon fell ill, and the treatment he received had a big impact on his health and left him unable to accompany her. He could no longer bear the daily 4-hour journey from the governorate where they live to Alexandria, so the burden of work fell entirely on her.

Sabrine wakes up at three in the morning or earlier and comes back home at eight in the evening. Her daily journey begins with a ride from her remote village to the Tanta Market where she buys her vegetables directly from the merchants and farmers. She then - like many other rural women - loads the goods on a delivery truck, then takes the train from Tanta Train Station to Alexandria. Her journey back home is just as long.

Sabrine had been coming to the market with her mother since she was a child. Her mother was the breadwinner in the family since her father was elderly. She quickly learned the trade and started selling and earning money. Sabrine was only twelve when her mother passed away and she had to take her place. She says that she has been helping support her family ever since she was 9 years old.

She says that her average daily profit is 250 Egyptian pounds but may go up to 400 or 500. It is also possible that on some days she doesn’t sell anything. "I would still have paid for my transportation, the transportation of the vegetables, and sat in the cold for nothing." Sabrine also pays the owner of the fruit shop next to where she is set up, 1500 Egyptian pounds per month, at 50 Egyptian pounds per day, an amount which is fixed regardless of whether she earns anything that day or not.

Through her work, she has been able to pay off her debt and build a 4-storey house. She lives on the ground floor, which she proudly describes as “Super Lux”, while the other floors are being set up for her children. Her eldest, Malak, is a university student, and the youngest, Rasha, is 4 years old.

She considers herself "the head of the household", as she is the primary breadwinner and the one who manages the finances. She also insists that there is mutual understanding and trust between her and her husband. He owns and rents out a small piece of land, but "it doesn’t even cover its upkeep. It is useless and won’t help us build a future."

Her husband's illness not only increased the burden of financial responsibility on her, but his absence also makes her more her more vulnerable to verbal harassment from customers and other vendors alike. “That husband of yours must be blind, a woman like you shouldn’t spend a day at work. You should be kept in a shop window like a doll. If only you were my wife…”

Sabrine uses a nearby public bathroom, originally designated for men. She performs Wudu’ (ablution) there, and she prays seated on her wooden chair next to her little stall, not only because she suffers from back pain, but also because she once injured her knee by falling off the train station’s platform while carrying a load of cheese (7).

When she was pregnant with her youngest daughter, Sabrine worked up until a week before giving birth. Even while pregnant, she continued to carry the heavy sacks. 40 days after giving birth, she was back at work accompanied by her baby. She says it is normal for rural women to carry around their babies while they are still breastfeeding. Eventually, Sabrine had to wean her baby early because was away from her for 14 hours a day, and she ended up leaving her in the care of her eldest daughter.

Sabrine’s husband used to accompany her, but he got sick and could no longer bear the daily 4-hour journey from the governorate where they live to Alexandria, so the burden of work fell entirely on her. She gets up at three in the morning or earlier and comes back home at eight in the evening. She considers herself "the head of the household", as she is the primary breadwinner and the one who manages the finances.

Despite her financial success, Sabrine dreams of "staying at home and being with her children." She claims that she will stop working after securing her children’s future, adding that she would like them to have a life that is better than hers, one where they never want for anything. But she is also content and believes that her life has been written by fate. She actually wouldn’t want her daughter to work after graduating, as she would prefer that her daughter’s husband be the one who works hard for his family. Sometimes, she would watch a customer and his wife talking and overhears a question like "What would you like to eat today?", and that is enough to make her emotional. She laments: "No one has ever asked me that."

Souad: The socks’ saleswoman

On the sidewalks of a quiet area far from the market sits Souad (60 years old), clad in a black abaya and niqab, selling socks, keffiyehs, and other accessories for women who wear the veil or niqab, including gloves and wristbands. She has been working in this business for thirty years, starting off with selling some basic goods next to her house in a popular neighbourhood before she settled into her current location.

Souad’s father had passed away while she was still in elementary school, so neither she nor her brothers completed their education due to their family’s economic situation. “Who would have fed us?” Souad married young and had four children with her second husband who was unemployed, physically abusive, and an alcoholic. With ripped gloves on her hands, she points to bruises and scars on her forehead and arm. Her husband is also the reason she is missing her front teeth. Souad knew she had to work to support her children, so she borrowed 16 Egyptian pounds from one of her relatives to buy her first batch of merchandise which she started to sell, the way she saw others doing in the market. Her husband started asking her for money, but when Souad refused to give him her money, he would physically abuse her. He would also vandalize her stall, forcing her to move to another location. Souad filed for divorce and got it, but her ex-husband continued to stalk her, forcing her to move from one area to the next. Souad couldn’t even send her children to school anymore because she was afraid that her husband would kidnap them and claim that she had lost them. She eventually enrolled them in a literacy program so they can learn to read and write.

Souad never considered re-marrying, not just because of how much she had suffered in her previous marriage, but also because she didn’t want her children to have a new stepfather. They had become her only concern and hope in life. Her children grew up and got married, and Souad opposed the idea of her daughters doing her line of work. She believes that marriage is better for them, adding that “when a woman makes money, she tends to snub her husband.” Nevertheless, her daughter ended up following in her footsteps after her own divorce. The mother taught her daughter and set her up on her own in another area, while one of her sons also works as a street vendor, selling tea next to a mall.

Souad’s father passed away while she was still in elementary school, so neither she nor her brothers completed their education due to their economic situation. “Who would have fed us?” Souad married young and had four children with her second husband. He was unemployed, physically abusive, and an alcoholic. With ripped gloves on her hands, she points to marks and scars on her forehead and arm. Her husband is also the reason she is missing her front teeth.

She gets up every morning at five and takes a tuk-tuk on her daily commute from her home in one of the popular neighbourhoods to the sidewalk where she sets up her goods on a plastic rug and sits in front of them on a chair. At three in the afternoon, she takes the tuk-tuk back home, paying "twenty Egyptian pounds each way". Once at home, where she lives with her son, she does the household chores, such as cooking. She says that what she earns barely covers her expenses, since the rent of her apartment alone is 450 Egyptian pounds per month, excluding water and electricity (8). She also helps out her divorced daughter, and her son-in-law when he needs it. Handouts from people make up an important part of her income, in addition to a monthly social pension of 320 Egyptian pounds.

Souad prefers working and talking to people to spending her days at home. She explains that her work has given her rich life experiences and taught her how to read people. “It’s the school of hard knocks out there”. She also prefers being self-employed to working in a factory. "It’s better than having an employer yelling at me or telling me what to do and where to be."

When I asked her what the difficulties of her job are, she responded “the carrying and lifting” as well as haggling with customers. On rainy days, she puts some plastic bags on her head or takes cover under a nearby tree. When the weather gets really bad she stays at home, which has a significant effect on her budget. In addition, because the mosque next to where she is set up doesn’t have any facilities for women, there is no place for her to use the bathroom, and she needs to wait until she comes home in the evening.

Samra: The cheese vendor

Every day from morning to evening, Samra, a woman in her fifties, sits by the entrance of a building, selling cottage cheese and eggs. She has been doing the same job, in the same place next to the city’s markets, for 37 years. Her journey down this path started after her mother-in-law, who was a young widow with six children, passed away. “She took care of them and was able to financially support them through her work. But then, she got sick and died young.” Samra, who comes from a village in the Beheira Governorate, added that it was her mother-in-law’s work that had made her sick. Still, she took her place after her passing. “She was the one who taught me. She used to pray for me, until her last days.” In addition to their own two children, Samra and her husband, who was the eldest son, became responsible for the education and future of his siblings, after both their parents passed away. Now Samra is only responsible for her youngest daughter, who is in secondary school, and she dreams of the day she will see her as a beautiful bride.

Samra's husband worked in a textile company in the Beheira Governorate, but he - like the rest of his colleagues - was forced to retire early. "They made him retire early so they wouldn't give him his full pension. All these companies and factories are shutting down, there aren’t any left. They are all being sold off.” Samra is sad for all the young people these days who work without contracts or insurance, including her son who is married with children, and who works in a shop.

Although Samra inherited this profession from her mother-in-law, she wouldn’t want to pass it down to her daughters: “I don’t wish it on anyone. It’s a wretched kind of work, my dear. You get up really early, it's back-breaking and gruelling. I don’t think this new generation would be able to put up with all of that.” (9)

Samra’s journey down this path started after her mother-in-law, who was a young widow with six children, passed away. “She took care of them and was able to financially support them through her work. But then, she got sick and died young.”

While a customer is waiting to buy some cottage cheese, Samra calls out to one of the workers in the market and asks him to buy her some Foul (fava beans) - her morning breakfast - from the nearby bean cart. He brings it to her quickly, hot in a plastic bag. She starts telling me about her cheese. "We get this cheese from the farms, it’s homemade, and it’s much better than factory-made cheese. There are vendors who buy from the factories, but this is better."

When the police conduct raids against the vendors, Samra quickly carries her goods behind the gate she usually sits in front of and closes the door. “I watch them through the keyhole until they leave”; she then resumes her work. Sometimes there are "good people" who overlook her, but when it’s a large raid, "God have mercy on us!"

Samra's husband worked in a textile company in the Beheira Governorate, but he - like the rest of his colleagues - was forced to retire early. "They made him retire early so they wouldn't give him his full pension. All these companies and factories are shutting down, there aren’t any left. They are all being sold off.”

Samra does not own any land, but she says she is happy that she was able, through this work, to provide an education to all the children she was responsible for and get them married. She seems completely satisfied, "Our Lord has really blessed me... Perhaps these are the workings of my mother-in-law’s prayers." She performed the Umrah pilgrimage twice. She now hopes to get her youngest daughter married and secure her future, as well as go on the Hajj pilgrimage.

Amaal: The “feteer” maker

Inside the wide entrance of one of the buildings in the fancy part of the city, a neatly dressed young woman stands behind a table with feteers - flaky Egyptian layered pastry - and other homemade baked goods. Behind the easy-to-spot young woman is a small door that passers-by may not as easily notice. Behind that door is the hidden space where this tale begins.

Past those doors, you will find yourself in a poorly lit narrow room. The bad lighting is the only thing stopping the room from being pitch black even though it's broad daylight outside. There is an oven with a small tank of gas, an old-fashioned radio hanging on the wall, and a lonely backless plastic chair, on which the friendly lady and her daughter insisted I sit. I notice, next to the nearby wall, a small plate with some cheese and tomatoes on it. On the other side is a door that, as I was told, leads to the bathroom and the atrium. In the middle of the room is a high table with a wooden pallet, where Amaal stands, in her flour-covered house robe, making the feteer. From the wooden pallet to the oven, and from the oven to the table outside, the hot pastries are showcased in plastic bags, waiting for customers.

"Amaal" is 42 years old. She is married to the building’s caretaker and they have five children. The eldest is twenty years old, and the youngest is in elementary school. This small room that never sees the light of day was where the whole family lived for years. But as the family grew and the children got older, the room became too crowded. So Amaal asked the landlord’s permission to move to the roof, into what she called “the laundry room,” and to turn this room into a “workshop” where she prepares her baked goods.

Inside the wide entrance of one of the buildings in the fancy part of the city, a neatly dressed young woman stands behind a table with feteers - flaky Egyptian layered pastry, and other homemade baked goods. Behind the easy-to-spot young woman, is a small door that passers-by may not as easily notice. Behind that door is the hidden space where this tale begins.

Amaal’s husband worked as a blacksmith on construction sites but got injured while trying to break up a fight ten years ago. She says that one of the guys in the fight hit him with a wooden club and dislocated his shoulder. He has been unable to work ever since.

Amaal used to work as a housekeeper, but she says she can no longer endure the work due to her back pain. “I could no longer lift or move the mattresses.” So this business endeavour became the way for her to pay for the family's expenses. Particularly since the only income that her husband receives is 500 pounds from the property owner’s co-op, “which he keeps all to himself. He says it barely covers the cost of his cigarettes.” He sometimes even asks her to give him some of what she earns, but she refuses: “I have daughters to support and put through school.”

Amaal doesn’t just suffer from spinal pain, she also has a blockage of arteries in her hand and needs an operation. She is afraid of going through with it because she is worried about complications that could make her unable to work, since no one else can take her place. She is particularly worried because she would need to perform the surgery in a public hospital. “I would rather deal with blocked arteries!” The pain in her hands makes it hard for her to carry things. It gets worse at night when her hand goes numb and almost paralysed. “Every day, I wake up in the morning and pray for God’s help, and He helps me pull through.”

Amaal's day begins at five in the morning, she goes down to the room and works until four or five in the evening. Her daughter helps her with baking and also performs household chores. When there are leftovers, she takes them door to door to families who may want to buy some. “People who work in offices are comfortable. They spend their day drinking tea and if they miss a day of work they still get their fixed salaries. Meanwhile, if we take a day off, we make nothing that day.”

In the summer season, and in Ramadan, when there is less demand for feteers, Amaal sells prickly pears or other fruits in front of the building. “With all of our expenses, even all of this is not enough”. She adds that the apartments in the building are rented according to the old leasing system (5 or 10 pounds per month) and that the residents give her very few handouts, if any. No one gives without expecting something in return, and she is no longer physically able to do the work of a housekeeper. Amaal says there are those (who don’t live in the building), who give her monthly handouts. Some have even helped with her daughter's marriage trousseau. As for charities, she has noticed through her first-hand experiences with them that they do not deliver the donor’s money, which is in the thousands, to the people in need. She believes that donors should give directly to the people in need without an intermediary.

“I have been breaking my back with work for 25 years. I see wealthier women being asked by their husbands if they need anything, and I think to myself, no one has ever asked me that!"… Amaal’s words are verbatim Sabrine’s words!

Amaal worries about many things. She worries about the cold winters, the fact that they don’t have enough blankets, about the cold air coming in from the broken windows, the fact that she can't afford to buy a sweater, all the family’s expenses, and the high cost of living. She also worries about how she was scammed by a merchant who sold her watered-down honeycomb, which she bought for two hundred Egyptian pounds to offer to her customers with their feteers. Then there is her husband’s changed behaviour and his mistreatment of them. “When you are tired and miserable, a nice word is all it takes to make you feel better, but when you can’t find even that…” She is haunted by the seemingly never-ending daily grind. “We live this misery every day, you go to bed to it and you wake up to it. This is our life! The days go by and then one of those days we die and that’s it… It’s our fate. Maybe we will have better luck in the afterlife,” she says.

"I found myself thinking the other day, wouldn’t it be nice to just relax, find someone who would spend his money on me while I just stay at home. I have been breaking my back with work for 25 years. I see wealthier women being asked by their husbands if they need anything, and I think to myself, no one has ever asked me that!" Those are verbatim Sabrine’s words.

Amaal hopes to find someone to help her get her daughters ready for marriage. She also hopes that one day there will be "a little bit of justice" and that the rich will feel for the with poor.

________________________________

Appendix: stats and information

1- According to the report titled Women and Men in Egypt 2015, issued by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, the percentage of workers in the formal sector is 53.2%, compared to 46.7% in the informal sector.

- Distribution of workers in the two sectors according to gender is as follows:

• 55.2% of working women work in the formal sector, compared to 44.7% in the informal sector.

• 52.7% of employed men work in the formal sector, compared to 47.3% in the informal sector.

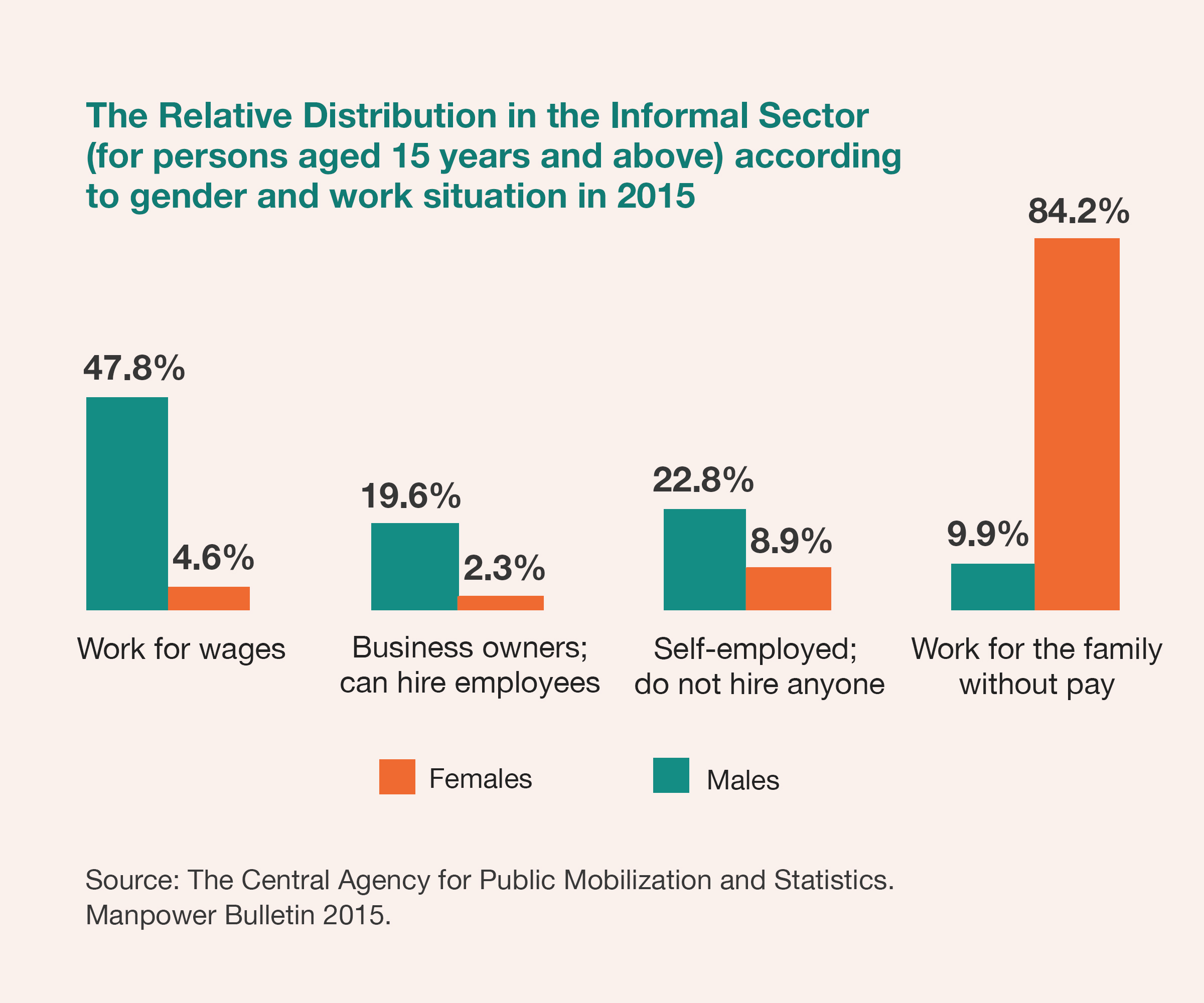

- The percentages of workers in the informal sector are distributed as follows:

- Percentage of female breadwinners:

In urban areas: 17% --- 44.7% of which are illiterate, while 83.9% are widowed or divorced.

In the countryside: 16.5% --- 66.6% of which are illiterate, while 70.9% are widowed or divorced.

The highest percentage of female breadwinners was recorded in the rural governorates of Qena and Sohag, respectively.

- Women and the labour market in Egypt:

Women represented 23.6% of the total labour force, compared to 76.4% for males (whereby the labour force is people of working age who are either working or looking for work).

The unemployment rate among females was 24.2%, compared to 9.4% among males.

2- According to a study on the economic empowerment of women - issued by the World Bank in partnership with the Egyptian Government / the National Council for Women (May 2018):

- Women's participation in the labour force has not increased despite the increase in their educational level and the relatively high percentage of women holding university degrees. This is not only due to structural issues, but also has to do with cultural norms and traditions, since values and practices related to gender identity and the relationship between genders constitute a barrier to women's economic empowerment.

- The empowerment of women at the family level (having a voice in personal and familial decision-making) increases as their income and financial contributions within the family increase. Women who work for a wage feel particularly empowered. Women's participation in family-related decisions also increases with age and education level.

- Egypt ranked low on the World Economic Forum's 2017 Gender Gap Index. It ranked 135th out of a list of 141 countries when it came to gender equality within economic participation and economic opportunities.

3- According to the World Bank

58% of the Egyptian workforce does not have any social security – according to an English-language study by the Cairo Center for Development Benchmarking (CDB) entitled: Women Working in the Informal Sector: Current Status and Suggested Interventions.

4- Globally

75% of women working in developing regions work in informal jobs and without insurance (Women's Economic Empowerment Platform website, supported by UN Women).

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Serene Husni

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 12/03/2020

1- Names have been changed to maintain anonymity.

2. According to the International Labor Organisation (ILO), the informal economy consists of private businesses that are not legally regulated and unregistered (and thus are not taxed), and informal employment, which includes informal workers in both the informal and formal sectors.

3- It is estimated that there are five million street vendors in Egypt, of whom 15%, or approximately 750,000, are women. Alexandria has the largest share of female street vendors, as 55% of them are concentrated in this governorate.

4- Some vendors sit in areas designated for them and are safe from police raids. In other cases, according to one of the vendors, a friendly relationship may be established with an officer in the district’s police department, who gives the vendor a heads up before the raid happens or ignores them during the raid.

5- The government, through the Ministry of Social Solidarity, provides a monthly social pension, which is worth 320 Egyptian pounds for orphans, widows and divorced women. In 2015, the government launched the “Solidarity and Dignity” program which gives financial support to particular groups, such as the elderly, people with disabilities or chronic diseases, and prisoners with school-age children, under certain conditions. Although the value of this support is slightly higher than the social security payments, both are still much less than what is needed to meet the requirements of daily life in Egypt, especially once you take into account inflation.

6- Those who are enrolled in school, ended up being pulled out just a few years later due to their family’s financial situation. Besides poverty, Sabrine also mentioned the mistreatment of the students at the hands of the teachers, as a reason people quit school.

7- Some of them get hernias due to carrying very heavy weights.

8- The room she was living in was flooded, so she was given an apartment (a room, hall, bathroom and kitchen) in a random area as a replacement, but it was unfit for human use, so she locked it up and rented another one.

9- In other cases, the rural woman may take her daughter (or son) with her to where she is set up for work so they can learn the profession, believing this is better for them than a school education.