This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Two major socio-political factors structure the anti-COVID vaccination process in Algeria. On the one hand, the government finds itself obliged to live up to its promise to secure the vaccines, while noting the unjust distribution of vaccines, especially between the developed capitalist countries and Africa, the latter having been allocated a mere 1% of the 3 billion doses administered worldwide (1).

The political “wait-and-see” approach leads to an incantatory and recurring speech: “During the period from 11 to 18 July 11, 2021, we will receive four million doses of vaccine” (statement of the Minister of Health, July 8, 2021). During the last 5 months (February to June, 2021), health officials have received 2.5 million doses of vaccine. On the other hand, the acute criticisms regarding the slowness of the vaccination process have forced health officials to explicitly adopt an offensive discourse about the imperative massification of vaccination.

It took five months for the anti-COVID vaccination campaign to turn into a political issue, closely linked to the directives of a voluntarist nature: a free vaccine for all. Officials had to take this decision due to the insufficient control over the pandemic, characterized by an increase in cases of infection with COVID-19, as shown by official figures (2).

In the logic of political continuity, the Algerian power resulting from the presidential elections of December 12, 2019, has reproduced the absurdity of its sub-analysis of society, which could not be put to good use during the period of the pandemic. Popular discourse uses this very relevant metaphor: “They took us for a football” (Mebtoul, 2021). Moreover, society was not much concerned with the epidemiological investigation efforts. After becoming subjugated, society was labeled as an empty jug that only needs to be mechanically filled with knowledge and attitudes. Finally, the mechanism for calculating infection cases set by the health authorities excluded private health care institutions and pharmacies, which means that thousands of cases were not taken into account in the official daily records (Mebtoul, 2021).

The Hirak in Lockdown Algeria

02-02-2021

Based on our field experience in health care structures in the city of Oran, we sought to understand the differences between what social actors say and what they do about vaccination, whether those actors are public authorities, health workers, or people who have received the vaccine. In the first section, we shall address the voluntarist and projected position of health authorities who sought to carry out a rapid “grafting” of vaccines by multiplying the presence of vaccination centers in social and professional spaces. Secondly, we shall highlight the obstacles and detours that stand in the way of the “act of vaccination”, due to the lack of transparency and the unequal access to vaccines, which deeply mars the daily progression of the vaccination process. Finally, we shall address the vaccine upsurge since July 2021, which is the result of strong pressures, some of which are brought about by the new Delta and Alpha variants, but the greater part of which is the pressure exercised by the family institution. The latter compensates for the shortcomings of political leaders and health institutions, by playing a crucial role as a mediator and transmitter of information and news to the members of the family in order to encourage them to go through with the vaccination.

Arbitrary and vertical voluntarism

The “vaccine emergency” seems to be the most recurring phrase used in the discourse of Algerian health officials who have multiplied the number of vaccination centers (mosques, shopping centers, public squares, schools, etc.). According to official figures, over a five-month period (February to June 2021), only 2.5 million people have received the vaccine in a country of 43 million people. As of June 9, the city of Oran recorded a 3% vaccination rate among its (more than) 2 million inhabitants.

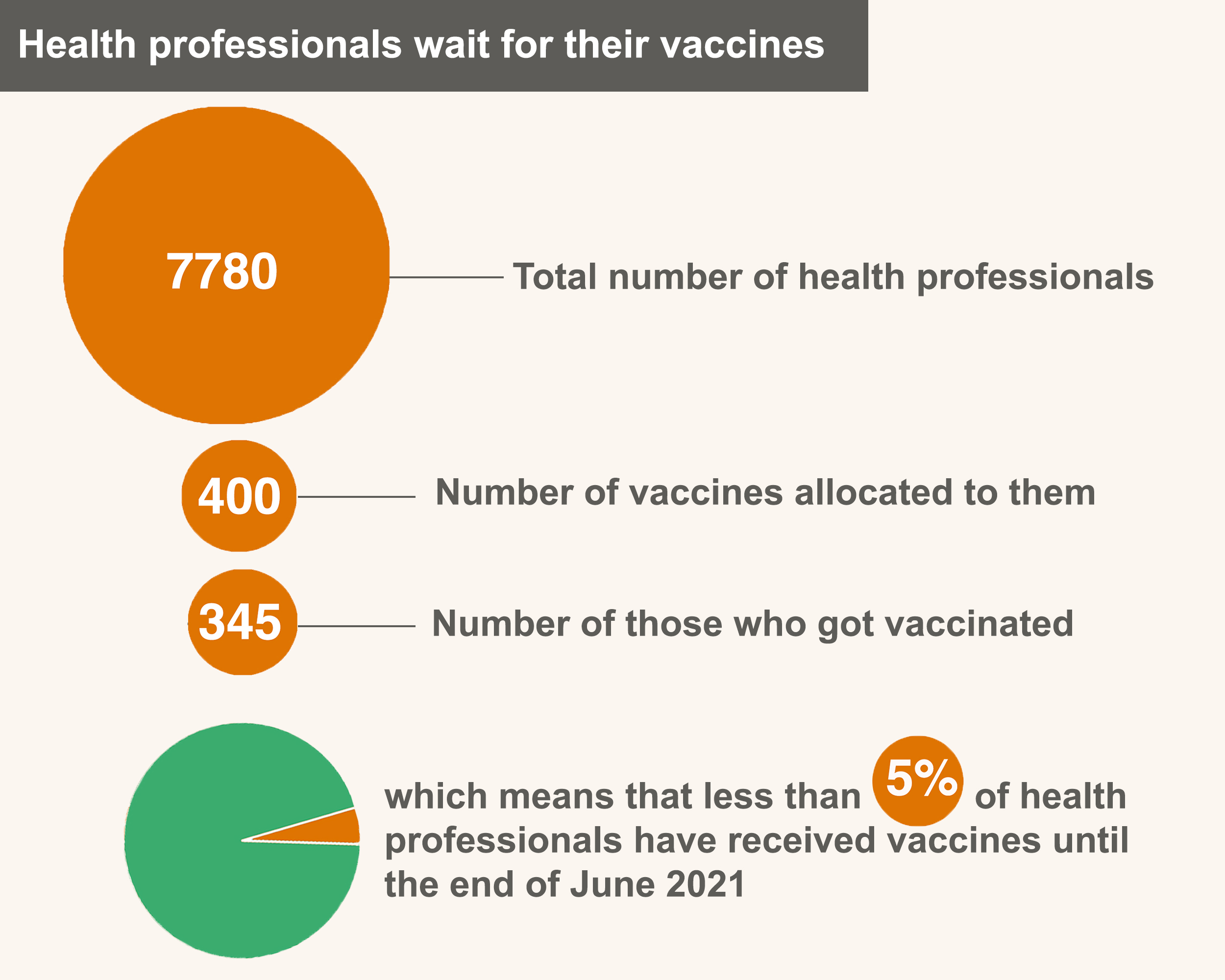

For the first six months, the vaccination process remained extremely timid and sporadic, subject to multiple fluctuations in a socio-medical context characterized by an information opacity. As of June 29, 2021, no more than 345 doctors and paramedical staff had received the vaccine, out of a total of 400 doses allocated to 7,780 health professionals, meaning barely 5% of them were vaccinated.

The suspicion - as well as the various convoluted practices in the vaccination process - that plagues large sectors of society is linked to the absence of political transparency and the lack of direct contact with citizens. Therefore, the Algerian authorities abide by their promise to locally manufacture the Russian “Sputnik” vaccine starting from September 2021; something the authorities believe is supposed to create a feelings of national pride.

During the course of their daily activities, physicians sense the pressure of this voluntarist vaccination policy imposed from above, by a strictly arbitrary logic that deems the number of vaccinated people as the number-one concern of the vaccination process, regardless of the technical and social working conditions. “There was no campaign! This is pressure! It is incompatible with the needs of the population! A lot of demands here and there, registrations and numerous documents here and there, etc... whereas the vaccination process is very simple,” says a general practitioner; she has 29 years of experience and works in a polyclinic in Oran.

The close observation of the vaccination process carried out in a commercial district, which has become known as “the new city” in Oran, is enriched by the daily influx of people from the surrounding regions. Vaccination is carried out in tents into which the vaccines are transported in small portable refrigerators. The hot weather exacerbates the already tense atmosphere at the site. Everyone is on edge: citizens who are losing their patience during the long wait, and health workers – understaffed - who work in inhumane social and technical conditions, with no water to quench their thirst, and no electric fans to alleviate the scorching heat. Another tent was set up to receive people waiting their turn. More than thirty people sit on chairs, while the less patient citizens try to get clarifications from the overwhelmed health workers who can no longer hear each other or others. Just next to the tent, dirt and rubbish are visible in the shopping square and on the sidewalks, paradoxically coexisting with this microbiological act represented by the vaccination process (notes taken on 8 July 2021).

The doctor responsible for vaccination in this tent notes that the site is not suitable for the process. The vertical management of the vaccination process takes place in the social distancing between “them” and “us”; that is, between the local political and administrative officials who hearken to the central authorities, having to implement “their” circulars, and health professionals who find themselves in direct contact with the population that waits for accurate information about various vaccines. The working conditions of health workers are difficult, fraught with problems of all kinds (lack of resources, various forms of misunderstandings with the administrative hierarchy), yet these workers can see that they are not granted any social recognition by the public authorities. The doctor is aware of this. “This is not a work environment,” she says.

Vaccination is carried out in a tent containing the vaccines, transported in small portable refrigerators. High temperatures exacerbate the tensions on the site and everyone seems to be on edge: citizens who impatiently wait, and the understaffed health workers, who work in inhumane social and technical conditions. The doctor responsible for the vaccination in this tent believes that the place is not a suitable environment for the vaccination process.

The legislative elections of June 12, 2021, boycotted by more than 80% of the population, had revealed the frailty of the Algerian political power and further weakened it, leaving it with no other option but to move forward in its political continuity, doing the one thing it knows how to do best, namely enforcing authoritarian measures which are incongruous with the aspirations of the Algerian people. Politics have an important impact on the day-to-day functioning of healthcare structures. Ordinary people find themselves pushed into a social and medical labyrinth in the absence of an accurate mapping of vaccination centers and spaces. “Come back next week,” “Register and we'll call you back on the phone,” etc. The socio-organizational ambiguity reproduces the same convoluted routes taken by those who own some kind of relational capital, the only “normalized” criterion in society, allowing them to ensure a swift vaccination in dignified conditions.

Convoluted practices and unequal access to vaccination

The scarcity of the doses that are distilled in an arbitrary and vertical manner to the polyclinics, as well as the social invisibility of the vaccination campaign, have favored informed people; those who hold firm cultural and relational capitals, giving them priority in obtaining the first doses of the vaccine. “Initially, we received 20 doses, which the director distributed to his friends,” a general practitioner tells us (55 years old, 25 years of experience working in a polyclinic in Oran). Even if at the same time, some people registered on the official “list”, an explicit referent on which the health staff strongly insists could also be contacted by telephone to be vaccinated. This dual social game which favors relational affinities is both formally visible and hidden, yet it structures the vaccination process in Algeria. More precisely, “priority people” are picked out of the formal written list, including the informal network of “friends and relatives”, reflecting the importance of relational capital.

Our investigative research shows that during the first six months (February-June 2021), the anti-COVID vaccination process remained very timid, sporadic, and subject to multiple fluctuations in a socio-medical context characterized by an opacity in the dissemination of information, which soon turned into obligatory measures that the population and the health personnel were expected to respect, whereas a health citizenship was unable to prevail in the healthcare spaces.

At the Oran University Hospital Center, the Department of Occupational Health was involved in the vaccination process which was previously exclusively the responsibility of health professionals. The discourse of the practitioners responsible for vaccination reflects a bleak social view of the process: “A lot of noise for very few doses,” says a female occupational physician who is in charge of vaccination. As of June 29, 2021, only 345 doctors and paramedics have been vaccinated, out of a total of 400 doses allocated to an estimated 7,780 health professionals, which means barely 5 percent of the health professionals in Algeria had been vaccinated.

“Health workers who have accepted the vaccine are those who had witnessed the passing of a colleague in the hospital, or who had suffered from COVID-19 at a previous time,” says an occupational health physician. Some health workers waited for the vaccination process to become clearer in the hospital, and then decided to receive the vaccine. In the face of the unknown, most people waited for those courageous initiators, those who were convinced from the outset that the vaccines were necessary. That means waiting for the vaccination results of those “lab mice” who have embarked on the “vaccination adventure” from early on, as one occupational physician indicated (a female doctor from the Oran University Hospital Center).

The course of vaccination in Algeria is characterized by varying socio-medical chronologies. In the initial phase, the state of political anticipation lasted for five months due to the scarcity of vaccine doses and the tediousness of the vaccination process. This is not separate from the political situation, in which repressive measures overlapped with the legislative elections of June 12, 2021.

In the second phase, the government multiplied the number of vaccination centers in several public places, following an arbitrary and voluntarist policy, to give an immediate momentum to the vaccination process, which produced several forms of inequality between the “lucky” people who held some kind of relational capital, and the anonymous people thrust into a medical labyrinth.

The suspicion, as well as the various convoluted practices in the vaccination process, that plagues large sectors of society is linked to the absence of political transparency and the lack of direct contact with citizens. Therefore, the Algerian authorities abide by their declared promise to locally manufacture the Russian “Sputnik” vaccine starting from September 2021; an act which the authorities believe is supposed to create a feelings of national pride.

This dominant discourse is detached from the reality of the daily problems of the people who use the phrase “Bled khalia” (“Deserted country”) to describe their daily lives. The patterns of daily life are characterized by the profuse presence of irregular vendors and the absence of local authorities and “representatives”, revealing their social distance from the population. Public spaces are also riddled with accumulated waste that floods streets and sidewalks.

An Incomplete Algerian Symphony

28-02-2021

Finally, after the ban on the “Hirak” demonstrations, the authorities transformed the urban order into a repressive one as of May 2021. Under such political conditions, marked by the ban on free speech, the vaccination process can hardly translate into a smooth and relaxed vaccination campaign that can be well-received by the population. It seems that familial pressure and influence, fear of the virus and the hasty voluntarism imposed on health workers, seemed to be the dominant factors that prompted the surge in vaccination, which only emerged at the beginning of July 2021 onwards.

The family: An essential catalyst of the vaccination surge

The family institution partially replaces the local public authorities by occupying the position of the organizing group for the vaccination process. This institution provides information and sometimes directs relatives to a selected healthcare facility, where the wait time is believed to be shorter. The family also never hesitates to put one of its members in direct contact with a member of the health staff from its network of “acquaintances”. The trust, respect and recognized moral authority of a family member give meaning to the commitment to get vaccinated. The decision to resort to a specific healthcare facility under family influence reduces skepticism about vaccination and alleviates fears about its side effects. These concerns involve an often controversial and strong cognitive charge, socialized by the mainstream media and social media in Algerian society.

“I was informed by a relative of mine who lives near the clinic. I hesitated to get the vaccine because I had some concerns about the side effects, which were also discussed in one of our family sessions.”, Amina says (a 40-year-old woman, unemployed, had her first dose of the Chinese “Sinovac” vaccine, July 11, 2021).

The choice of the vaccination center is also subject to family negotiations, as people look for a health care center that can bring them a satisfying experience, reducing waiting times and allowing them to access the health information they need. Our previous research has shown that people, even when silent, closely observe the day-to-day functioning of the health sector. “I learned through my family that the local clinic provides vaccination, and that it might be a better choice than the polyclinic where there are too many people and therefore a very long waiting time. I was a little hesitant to get the COVID vaccine because of some Facebook posts. At the local clinic, the organization of the process was good. A doctor took my blood pressure and I was kept under observation for a while. But in terms of the information, there is still a lot to be done…”, Chérifa says (a 50-year-old woman, unemployed, had her first dose of Chinese vaccine, “Sinovac”, July 11, 2021).

One cannot underestimate the importance of the social construction of the health care system’s reputation during a vaccination campaign, the primary objective of which is to allow the voluntary participation of the population, including the social group which holds a sizable cultural capital. “My wife is a dentist. She works at the clinic. She informed me that people were getting vaccinated at her workplace without difficulty. We were reluctant to get vaccinated because we could not get clear information about the vaccination process. We got vaccinated because we were afraid of the disease, even if the side effects were not clarified to us. The vaccination session went well. I have no complaints. The doctor took my blood pressure several times because I am diabetic and hypertensive,” Ahmed says (a 62-year-old man, university teacher, had his first dose of “Sinovac”, July 11, 2021).

The family institution partially replaces the local public authorities, by occupying the position of the organizing group for the vaccination process. This institution provides information and sometimes directs relatives to a selected healthcare facility where the wait time is believed to be shorter.

This invisible, unrecognized and free cognitive labor provided by the family allows the acceleration of the vaccination of those related to them against COVID. It becomes part of the daily, banal, and self-evident routines of life, defined by the French philosopher Henri Lefebvre (1968), by “the sum of insignificances”. However, it is a central catalyst to the vaccination surge observed in socio-professional and public spaces.

Epilogue

The course of vaccination in Algeria is characterized by varying socio-medical chronologies. In the initial phase, the state of political anticipation lasted for five months due to the scarcity of vaccine doses and the tediousness of the vaccination process. This is not separate from the political situation, in which repressive measures and the organization of the legislative elections on June 12, 2021 overlapped. In the second phase, the government multiplied the number of vaccination centers in several public places, following an authoritarian and voluntarist policy, in order to give an immediate momentum to the vaccination process, which produced several forms of inequality between the “lucky” people who held some kind of relational capital, and those ordinary people thrust into a medical labyrinth. Three factors have catalyzed this vaccination surge: first, the health officials, motivated to engage in a vaccination emergency; second, the fear of the new Delta variant (among other variants); and third, the cognitive effort and support that the family provides to encourage its members to actually go through with the vaccination.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 23/09/2021

1) French newspaper Le Monde, 11 and 12 July 2021.

2) The Algerian authorities proudly announced low records of COVID-19 positive cases, which ranged between 300 and 350 cases per day in the period from February to June 2021. Starting from July 2021, the authorities were forced to admit that the number of cases had become more than 1,000 per day, revealing that hospitals have reached their maximum capacity with the influx of COVID patients. Fatalities had risen to more than 20 per day, according to official figures.