This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

It was obvious that the wisest way to save the lives of the citizens of a Yemen burdened with the woes of war and encumbered by the collapse of its entire health system, while suffering from the widespread malnutrition and epidemics, was to quickly provide vaccines to the largest possible number of the population. That is because all other options, including precautionary measures, are highly unlikely to succeed in curbing the disaster whose extent and severity are unpredictable in magnitude, especially in light of the emergence of new waves of the pandemic.

The first shipment of COVID-19 vaccines arrived in Yemen in late March 2021, through the COVAX Facility, comprising 360 thousand doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, as “the first batch out of 1.9 million doses that Yemen is set to receive during the year 2021,” according to a statement by UNICEF, while the Yemeni Ministry of Health declared that more than 6 million doses of the vaccine were bound to reach Yemen in phases. So far, Yemen is ranked fifth on the list of Arab countries with the most delay in vaccinating its citizens.

The Ministry of Health in the internationally recognized Yemeni government had declared in July 2021 that Yemen would receive 151 thousand doses of the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine at the end of that month, out of a total of 504 thousand doses the country would eventually receive. However, the specific date of the arrival of those doses was not disclosed. The new batch of AstraZeneca vaccines, which the ministry said would arrive in August, was also shrouded with the same kind of vagueness. The Ministry of Health was obviously floundering as its efforts to speed up the process of obtaining the vaccines were proving less than adequate.

Covid-19 in Yemen: A Weaponless Battle

08-06-2021

By the beginning of June 2021, 167 thousand people in Yemen had already received COVID-19 vaccines during the first vaccination campaign in the 13 governorates governed by the internationally recognized official government, out of the total 22 Yemeni governorates. Meanwhile, the Houthis, who control the rest of the governorates, refused to receive the vaccines, even though 10 thousand doses were allocated to the health staff in the regions under their power.

Lack of an emergency response

In Yemen, the notion that the vaccine is the only way to control the number of victims was somehow replaced by an inclination to undermine the value of life itself! Life was no longer treasured, or at least, that’s what it seemed like, based on what was happening in the country on a regular basis.

It is clear that the Yemeni government has snubbed what the World Health Organization calls “regulatory response”, which means meeting the legal requirements for importing vaccines, providing necessary authorizations for their administration, and expediting procedures for their provision across the country. In typically stable countries, these are standard procedures, yet in a country like Yemen, where the chances of maintaining preventive measures and saving lives are faint, those procedures become even more urgent.

In early April 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that “the World Bank has provided a $26.9 million grant for Yemen to fund emergency response activities related to the Coronavirus outbreak.” In mid-June, the World Bank also approved another financial grant of $20 million in support of the vaccination campaign. But these are very meagre sum, much like all the sums the World Bank had allocated to poor countries.

While the vaccine’s target group was initially limited to healthcare workers, the elderly, and patients with chronic illnesses, the general reluctance to take the vaccine prompted the Ministry of Health to amend its strategy, announcing that anyone who wanted to take the vaccine could do so. In an effort to diffuse the fear, the ministry made vaccines available for media workers and journalists, in the hope that those would use their platforms on social media to encourage vaccination.

The process of importing additional vaccines to expedite vaccination seemed as questionable and vague as everything else in this worn-out country, where it is never easy to find out exactly how things are being done behind the closed doors of the responsible government offices, and one can only look at the outcomes in the hope of gaining some understanding of an excruciating reality.

In early April 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that “the World Bank has provided a $26.9 million grant for Yemen to fund emergency response activities related to the Coronavirus outbreak.” In mid-June, the World Bank also approved another financial grant of $20 million in support of the vaccination campaign. However, these sums are not in line with Yemen’s exceptional needs in its current dire situation. The World Bank itself had made a statement in June 2021, indicating that it had provided more than 4 billion dollars for the purchase and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines for 51 developing countries, half of which are located in Africa. The sum is indeed meagre given the population of those countries, especially when contrasted with the shameful “vaccine extravagance” the world saw in rich countries.

Houthis’ denial and chaos

Already in control of most of the regions and governorates of northern Yemen, which are inhabited by more than 60 percent of the country’s estimated population of 30 million people, Houthis seemed to regard their response to the pandemic as part of their military strategy; one which has claimed many victims, either by death at war, from starvation, or due to illnesses under a collapsed health system.

The Houthi authorities took no action to bring in the vaccine, all the more refusing to receive the 10,000 doses that the official government allocated to health workers in Houthi-controlled regions. The decision aligns with the group’s previous views, as it had denied the existence of COVID-19, and only once reported a single fatality and 3 cases of infection by the virus in May 2020. Houthis consequently cared very little for vaccination, with their leader, Abdul Malek al-Houthi considering Corona virus as nothing more than “an American conspiracy”, as he said in a televised speech on al-Masirah channel in March 2020. Al-Houthi said he based his conclusion on the opinions of so-called “experts in biological warfare”, adding that “the Americans have worked for years... to use the Corona virus... by spreading it in certain societies.”

According to a Human Rights Watch report (1), on 23 April 2021, the representative of the WHO in Yemen, Adham Rashad Abdel Moneim, had said in a virtual conference organized by the UK-based charity organization “Medical Professionals for Yemen” on Yemen’s response to COVID-19, that the Houthi authorities initially agreed under pressure to accept 10,000 doses of vaccine. However, the vaccines were not delivered to them after the World Health Organization rejected the Houthis’ condition that the vaccines should be distributed exclusively by them, refusing any supervision by the World Health Organization.

Later on, Houthis requested only 1,000 of the 10,000 doses that were intended for the healthcare workers in Houthi-controlled areas. But, soon enough, the WHO’s representative, Adham Abdel Moneim, announced that 10,000 doses of vaccine had already arrived at Sanaa’s airport and were stored in coolers, according to a Reuters’ report in June 2021. Abdel Moneim stated that only members of the medical staff would receive the vaccines under the supervision of the World Health Organization.

By the end of May 2021, vaccination centers became overcrowded with people ready to take their shots, after a considerably lengthy period of reluctance, as a result of Saudi Arabia’s regulations which denied Yemenis entry for work or Hajj and Umrah, unless they show a certified vaccination document.

When Yemeni expatriates’ demanded to be included in the vaccination campaign, vaccination “brokerage” activities ensued, to the point that some vaccination centers shut their doors in an attempt to extort the expatriates, while imposing fees in exchange for the paper certificates proving that they had received the vaccine.

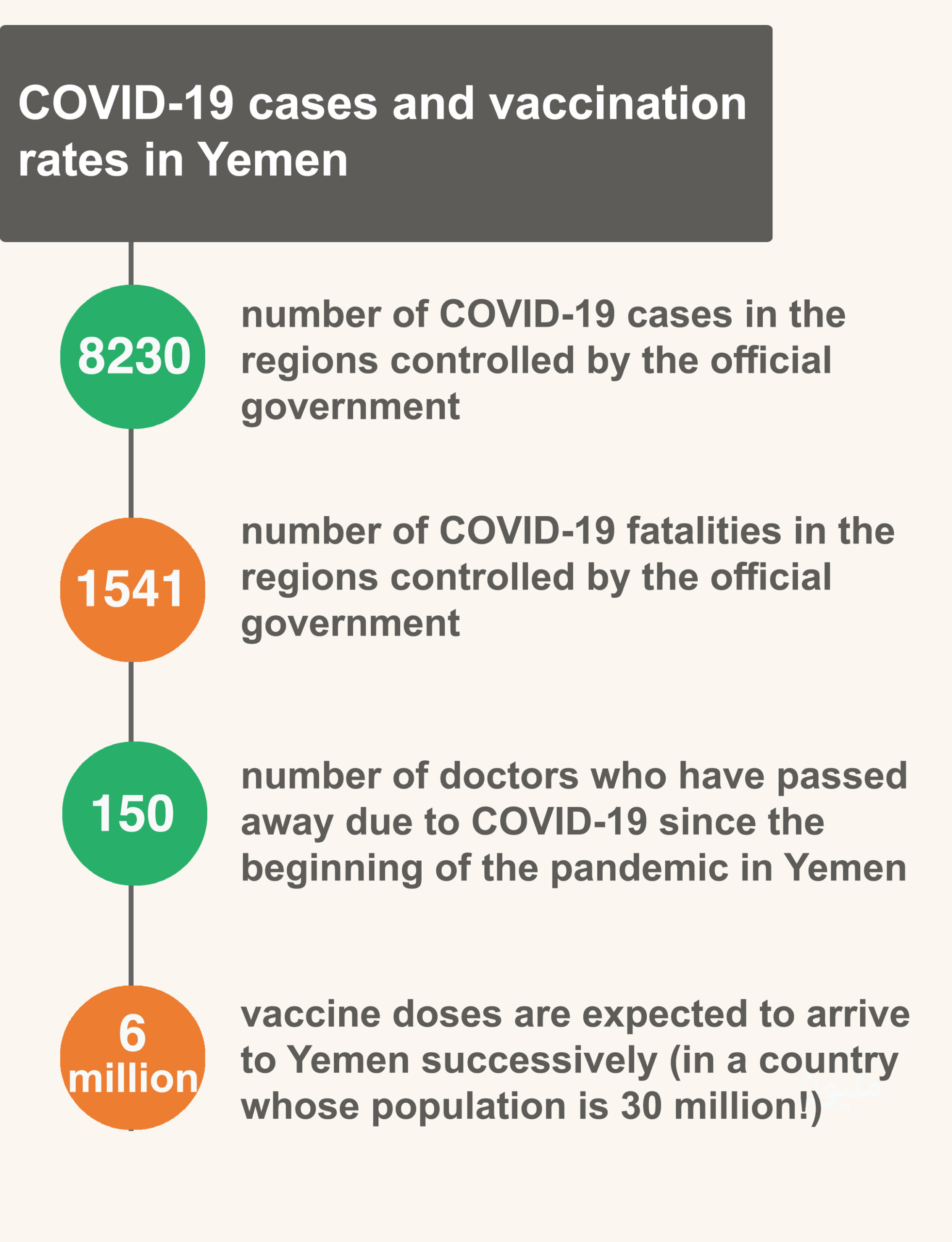

Several physicians working in Sanaa told the researcher that they had not been called to receive the vaccine. One of them said he had heard that shots available at Zayed Hospital. However, it seems that secrecy was one of the conditions for the Houthi group to allow vaccines in the areas under their control. According to the Association of Yemeni Doctors in Diaspora, at least 150 doctors have passed away in Yemen due to COVID-19 since the beginning of the pandemic, and most of those who passed during the first wave of the outbreak were working in hospitals in the capital, Sanaa.

From reluctance to acceptance

At first, things did not go according to plan in the parts of Yemen which are under the control of the internationally recognized government either. The first few weeks of the vaccination campaign saw an extremely poor turnout, probably due to the decline in the number of reported cases during the second wave of COVID-19, as well as due to rumors surrounding AstraZeneca’s allegedly “serious side effects, including fatal heart attacks”. As a result, the Minister of Health had to make repeated appeals to citizens to take the vaccine and ignore the false rumors.

Initially, the target groups for the vaccination campaign were limited to healthcare workers, the elderly, and patients with chronic illnesses, but the poor turnout and the general reluctance to take the vaccine prompted the Ministry of Health to modify its strategy by giving the chance for everyone who wanted to receive the vaccine to do so. In an effort to diffuse the fear, the ministry made vaccines available for media workers and journalists, in the hopes that those would use their platforms on social media to encourage vaccination through posting photos of themselves getting the shot and writing posts that confirm the safety of the vaccine. The preachers at mosques – perhaps directed by the Ministry of Endowments (Awqaf) – urged people to get vaccinated, too.

It was only a month after the first phase of vaccination began that the situation started to shift. By the end of May 2021, vaccination centers became overcrowded with people ready to take their shots, after Saudi Arabia announced new regulations which denied Yemenis entry into the country for work or Hajj and Umrah, unless they show an official vaccination document.

Thousands of Yemeni expatriates in Saudi Arabia had been spending their Eid vacations in Yemen, and instead of them going directly back to work in Saudi Arabia, they had to go to vaccination centers, which complicated things for the Ministry of Health… especially that many of the vaccine seekers came from governorates under Houthi control, where there are no vaccination centers. As a result, Yemeni health authorities opened additional vaccination centers in Aden, Hadramout and Taiz.

And in light of Yemeni expatriates’ demands to be included in the vaccination campaign, vaccination “brokerage” activities ensued, to the point that some vaccination centers shut their doors in an attempt to extort the expatriates, while imposing fees in exchange for the paper certificates proving that they had received the vaccine. Consequently, the Minister of Health in the official government tweeted in late May, at the time when demand for the vaccine was peaking, writing that “CIVID-19 vaccines are free for citizens, and any fees imposed are illicit. Violators among the employees will be held accountable and referred to investigation.”

After the first phase of vaccinations was concluded, another kind of brokerage surfaced. False vaccination certificates were issued to people who did not receive a shot but wanted to cross the border to resume their work in Saudi Arabia. Those certificates were identical to the official documents, except that they were given to unvaccinated individuals through brokers, for a payment of 1,000 Saudi riyals.

Nevertheless, crossing to Saudi Arabia with those counterfeit certificates was no longer possible after the Saudi Ministry of Health made electronic certificates mandatory, since those contained only accurate data.

Overall, the expatriates’ eagerness to receive the vaccine contributed to altering mainstream attitudes towards it, and people began to race to vaccination centers.

Problems with the second dose

The second phase of the vaccination campaign against COVID-19 was launched in late June 2021. Target groups were workers in the healthcare sector, the elderly, and persons suffering chronic illnesses, as they were supposed to receive their second doses of AstraZeneca vaccine. But since the door had been opened in phase one for anyone who wanted to get vaccinated due to the initial poor turnout, it was announced that the second dose would also be given to everyone who took the first dose between April 20 and May 7, while others who took their first dose after that date must wait for the second batch of vaccines to arrive. However, the second shipment has not yet arrived, which has sent the Yemeni expatriates who already took their first doses into a spiral of suffering as they wait for their second doses so they can be allowed to return to their work in Saudi Arabia. In addition, there were also several technical difficulties in the electronic certificate which has recently been launched.

After the first phase of vaccinations was concluded, another kind of brokerage surfaced, as false vaccination certificates were issued in exchange for 1,000 riyals to people who did not receive a shot but wanted to cross the border to resume their work in Saudi Arabia. Nevertheless, this was no longer possible after the Saudi Ministry of Health made electronic certificates mandatory.

And just like paper certificates had been forged (with an official stamp), a black market that sells vaccines emerged as well, in light of the expats’ high demand for second doses. In Yemen, a black market cannot be sustained away from the involvement of an official authority, especially since one of the requirements for obtaining electronic certificates is taking the shot at a formally recognized center, so that the certificate would include all the necessary data.

Some people who got a second dose of the vaccine on the black market reported that they had to pay at least $100 for it. Increased demand for the “black market vaccines” was a consequence of the Ministry of Health’s statement that the second dose of the vaccine should be administered after a period of 8 to 12 weeks from the first shot. When more than 12 weeks had passed for the people who took their first shots after May 10, and with no vaccines in sight for them, they grew impatient and were hasty to find dubious ways to obtain it.

The Ministry of Health in the official government went on to launch an online platform in July 2021 where those who wished to receive the vaccine could register. The ministry said that those who did not register would not be able to receive their doses, but only a few days after its launching, the ministry’s Health Education Center announced that the platform was being hacked. While many complained that they were unable to complete their registration, the Center insisted that this was due to heavy traffic on the website.

The Ministry of Health launched an online platform where those who wished to receive the vaccine could register, stating that people who did not register would not receive their doses. However, Yemen has the worst internet connection services in the region and the registration is only accessible to people with an internet service, a computer or a smart phone, all of which are amenities that most Yemenis in rural and remote areas or refugee camps lack.

Notably, the ministry did not specify which groups are entitled to register on the platform, even though the promised doses do not exceed 500,000 doses of either AstraZeneca or Johnson & Johnson vaccines. Yemen has one of the worst internet networks in the region, while registration requires that people have a stable internet connection and a computer or a smart phone, all of which are lacking amenities for most Yemenis living in rural and remote areas and in displacement camps. This means that vaccination will be exclusively available to the middle class and city dwellers, and even this group still reports several issues with registration, such as the platform’s failure to send them any kind of confirmation via their phones, as it is supposed to.

Signs of a third wave

Simultaneous with the poor governmental performance in dealing with the vaccine, it appears that a third wave of COVID-19 has begun to break put in some Yemeni governorates, where high rates of new infections have been recorded during the past few days.

On August 17, 2021, the Ministry of Health in the official government registered the largest number of daily infections since the second wave receded in late May, recording 39 cases in the governorates of Aden, Lahj, Marib, Taiz, Abyan and Hadramout, including two fatalities.

With this, the number of confirmed positive cases since the beginning of the pandemic in April 2020 have reached 8,230 cases in the areas under the control of the official government, including 1,541 deaths, according to the latest announced numbers by Yemen’s Supreme National Emergency Committee for COVID-19. The committee advised on September 8, 2020 to freeze any official events and gatherings to combat a third wave of the epidemic, days after the arrival of 151,000 doses of the Johnson’s & Johnson’s vaccine from the United States of America. Nevertheless, the official bodies’ capabilities to monitor and report cases are still very modest, and so it is estimated that these registered numbers make up barely 10% of the expected real number of infections in Yemen.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 09/09/2021

(1) Yemen: The Houthis are risking the health of civilians in the face of “Corona”, Human Rights Watch, June 1, 2021.