This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Part I: The Media

The crime of the August 4th, 2020 explosion in Lebanon’s capital city, Beirut, has left everyone in the country completely distraught and utterly exhausted. It may now seem that the moment has vastly outgrown the subject of this article, which appears to belong to an earlier, more optimistic time in the near past… A time when it was still believed that something could be done; something could be saved. This text initially set out as an attempt to scrutinize the cultural, artistic, media-related, and youth initiatives that crystallized with the October 17 uprising in Lebanon, as expressions of a latent vitality among the people who have refused to give in to the status quo, disobeying the limitations of the mainstream mediums of expression, as varied as their methods and perspectives may be. Today, taking into consideration everything the country has witnessed since October 17, 2019 until this moment (that is, after the two major dramatic events of the economic collapse and the Beirut Port explosion), it is perhaps necessary to repeat the question: “Is there a pulse still to be found in the country’s battered body? Are people still trying? And, most importantly, how do they try?”

For fear of drowning in the heavy gloom which lately seems to coat everything in Lebanon, one had better return to that fleeting moment of euphoric optimism that immediately followed October 17, 2019. That moment was a sort of a passageway in time between two stages, storing open possibilities and providing a glaring opportunity for change. The streets seemed ripe; ready to receive both discourses and actions that broke away from the rhetoric of the “post-civil war Lebanese Republic”. All that was being born out of the uprising labelled itself either “alternative”, “new", “revolutionary”, or “reforming”, but whatever its nature be, it was always characteristically filled with a unique zeal, an excitement for what was possible, and a desire to shake what had – for so long - been stagnant.

What had been stagnant is in fact the country's unmatched political system; one which has perched over every soul and stifled every aspiration for over thirty years. Understanding how this system has functioned can be helpful in realizing what the existence of such initiatives means under the country’s circumstances. Ever since the Taif Agreement in 1990, and with the succession of the Lebanese “civil peace” governments, politics has, by and large, been sucked out of public office positions in the country. Save for the routine party feuds, narrow sectarian/ partisan agendas, and quota distributions of state “shares” among the politicians, “politics” in its essence has always been lacking. Meanwhile, a peculiar and fragile internal agreement, which merely envelopes disputes and only releases them to the surface when need be, has been dearly preserved among all local parties. Indeed, they were all friends and enemies at the same time. The slimy word sometimes used in the media to describe them is the “Lebanese frenemies”. In this sense, the most popular of the uprising’s slogans “Everyone means Everyone” seems most fitting to describe the ruling class. Those in power make a point of perpetuating their petty feuds and failing to agree, and by doing so, they indefinitely accept the conditions that make state governance impossible. They (“everyone”) run the country’s affairs as they please, while maintaining a minimum of that which simultaneously keeps them all dissatisfied, feeling like their share in power could have been a little greater still.

The stagnant situation comprised politics which is void of politics; interested neither in public service nor in effectiveness. It was a business that ran on subservience and a deep-rooted clientelism, through which “those above” are allowed to circumvent the anger and frustration of “those below”. Temporary and permanent loyalties are bought and sold, namely along the sectarian divides in the country, providing the so-called “street legitimacy” or “popular representation”. In reality, clientelism and inciting fear on sectarian grounds were key strategies for politicians to maintain the loyalty of the people. Perhaps the mythical “state of institutions, law and order” that Lebanese citizens always hear so much about, is nothing more than a perverse relationship between different gangs and their cronies, rather than an organizing framework between a political system and constituent political parties on the one hand, and citizens who expect their government to provide their basic rights, on the other.

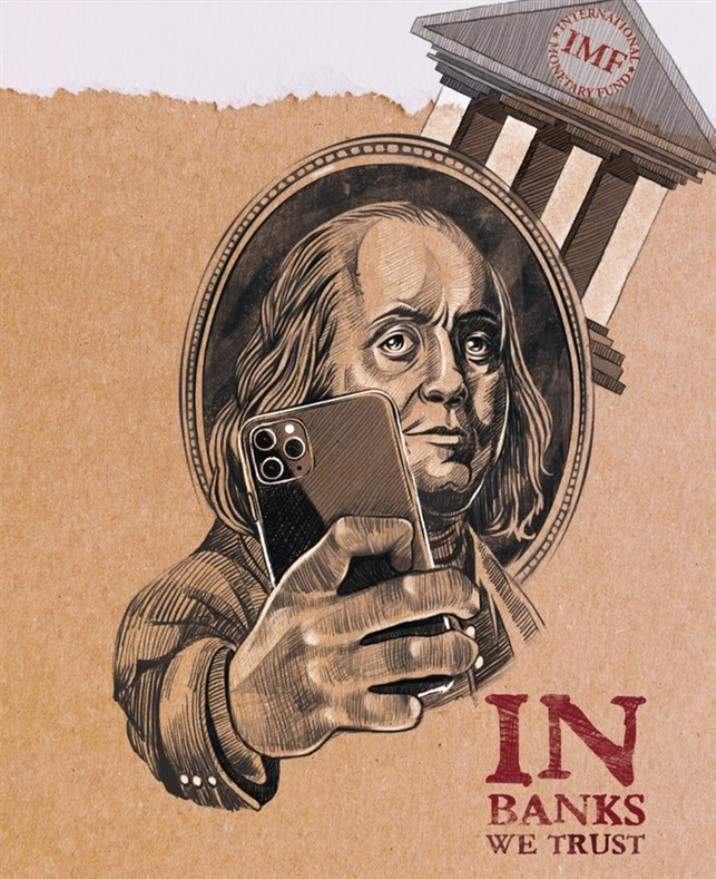

This structurally dysfunctional system has proven to stifle any real reform, yet it has been the norm in Lebanon. The relative calm before October 17 was the “normal” that preceded the plunge. Then came the unprecedented wildfires in the country’s western mountains, followed by the government’s intention to impose a so-called “WhatsApp tax” which sparked the first street protests. The new taxes coupled with news of an impending economic collapse quickly translated into a wide uprising across the country, from end to end. From there on signs of disaster manifested: the rapid decline of the Lebanese pound, the seizure of depositors' money in banks, astronomical increases in prices, and slaughtered dreams.

It was in this extremely complex, highly flammable, and dim atmosphere that these attempts and initiatives were born. If one insists on evoking the above-mentioned conditions as a permanent backdrop to the scene, it would quickly become clear that the task of penetrating this minefield of rigid political and social spheres in which all popular groups are implicated, is an arduous mission. Hence, it can be said that these attempts are indeed “adventures”, some of which are spontaneous, while a few are linked to alternative political projects. Nevertheless, could these initiatives, born in the exceptional moment of a popular insurgence, find ways to outlast their ephemeral circumstances and instead become long term standing projects?

1) Print and online Publications

It is no secret that the mainstream media in Lebanon is organically linked to political money. Media sociologist, Nabil Dajani, points out that independent (mainstream) media in Lebanon is a myth, and is in fact controlled by parties, political leaders and money-holders. He notes that most content on these platforms seems alien to the daily concerns of citizens, and leads to preserving, or even deepening division (1) . On the other hand, Lebanese newspapers have been successively dying out due to financing crises that have afflicted even the most prominent of them in the recent few years, creating an enormous vacuum in the press scene.

Remarkably, after the October uprising, several independent media and cultural initiatives decided to restore the tradition of paper publishing, next to online publishing, at a time when the enthusiasm for print was rapidly diminishing in the mainstream. In the following paragraphs, the text tries to introduce and probe some of those experiments, noting their certain heterogeneity and their distinct forms and contents. Their sparse discourses perhaps reflect the fact that the October uprising was also a space for many voices of a wide range of Lebanese groups that do not necessarily conform on every front, but who have agreed on reclaiming their voice in the media, as on the streets.

“October 17” Newspaper

On November 28, 2019, the first issue of the newspaper that chose “October 17” (2) as its name, was published. Its media website and printed newspaper were the outcome of many discussions and ideas that interacted in the squares themselves and emerged from the spontaneous dialogue circles that became staples of the revolutionary nights in all regions. In this spirit, the newspaper’s editor-in-chief, Bashir Abou Zeid, began his debut editorial with the line “A salute from the people, in the language of the people”.

The founders of the October 17 newspaper assert their complete independence, stating that their funding comes exclusively from donations from Lebanese participants in the popular uprising and from expatriates who wanted to be part of the movement even when they couldn’t physically be on the streets. Writers, designers, editors, and other workers are all volunteers. The newspaper is published on a monthly basis and distributed free of charge. During the days of the daily protests in the squares, the October 17 paper was handed out to the demonstrators in all Lebanese regions and had distribution points from Beirut to Nabatiyeh, Tripoli, Choueifat and other Lebanese regions, confirming the decentralization of the protest movement and the necessity of being present in all regions.

Upon its publication, October 17 was received as “the revolution’s paper and mouthpiece”, however, the newspaper does not claim an exclusive media representation of the uprising. In fact, it openly welcomes texts, photographs, and illustrations from everyone. Its content ranges from opinion articles to texts on culture and poetry, in addition to its main segment which shares daily documentation of the events in the streets. Its website also gives a permanent homepage space which honors “the memory of the martyrs of the revolution.”

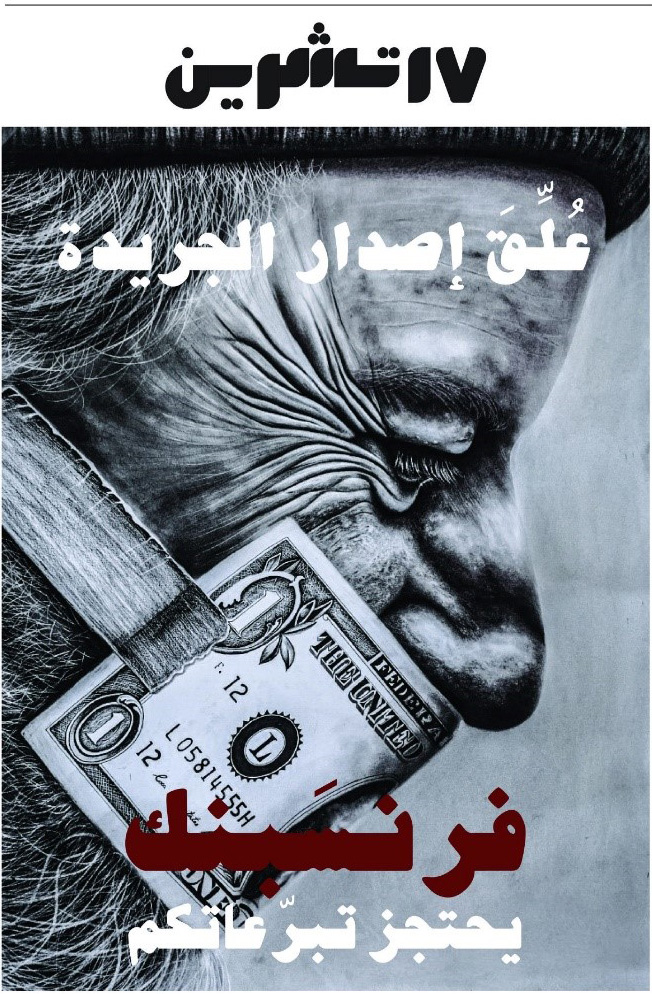

The paper itself did not escape the insolent abuses of the private banks. In March 2020, the October 17 newspaper announced that it would be suspending all publication due to Fransabank’s withholding their donation money, which had been collected two months earlier in their Fransabank account through the crowdfunding platform “Zoomaal,” according to a statement on the paper’s Facebook page. The founders of the paper protested in front of Fransabank’s Hamra branch, declaring in their statement: “We have no choice but to partake in this struggle which has been imposed on us, in order to survive. If they should empty our pens of all ink, we would continue to fill the papers using the ashes from the burned down criminal institutions.”

While the money is still withheld by the bank to date, the newspaper resumed printing in June 2020, with a fully volunteer-based staff and after launching another crowdfunding campaign that does not rely on banking channels. October 17 may have been the most widespread new publication among the crowds at the height of the popular insurgence, before the movement lost momentum, and it was the very first print publication/ website to be born out of the event, with its debut issue having been published in November 2019, only a month after the protests began.

“Al-Khandaq”

After the October 17 newspaper, yet another print publication emerged. The monthly newspaper, al-Khandaq (3) is a self-proclaimed “adventure in a crumbling world.” Its name, meaning “the trench” in English, plays on the word as a symbol of “taking sides” and assuming an unambiguous stance on political matters. The newspaper’s editor-in-chief, Bashar Lakkis, explains to Assafir al-Arabi that al-Khandaq adopts a clear choice based on its belief “that the battle against corruption is in no way separate from the battle against imperialism.”

“In our opinion, both of these confrontations go hand in hand,” he continues. “We’re not being idealistic, and we’re well aware that whichever side one chooses would prove to have its share of flaws and of benefits as well. Politics is, in fact, a group of compulsions that force one to find a balance between them. In short, we believed in the necessity of confronting corruption, together with the necessity of maintaining a confrontational front against the hostile United States of America and Israel,” Lakkis explains. Hence, the newspaper adopts the slogan “Resolution, Commitment, Confrontation,” and while its rhetoric is often viewed as close to that of Hezbollah, Lakkis categorically denies any affiliation to any party or group, guaranteeing that the project depends solely on people’s donations and the volunteer efforts of individuals who believe in the importance of the project and work in every way to keep it going.

“Yes, our main approach is related to preserving the resistance. However, we are calling for the resistance to turn into a revitalizing project that can reflect on all aspects of life... This is our explicit stance, and it is one which generally does not go down well with anyone in Lebanon,” says Lakkis. The newspaper appears to be, in part, a response to a renewed debate among the different groups of protests over Hezbollah's armed faction as a controversial topic and the party's political internal alliances and role in power. This issue is indicative of the broad spectrum of participants in the protests across the country and their varying perspectives on several matters, despite their consensus on some of the titular issues that brought them together in all regions over the weeks of the uprising.

On al-Khandaq’s website, one finds headings that address local matters and others which deal with wider scopes. Some of these headings are: Arab and international affairs, Africa, Israeli matters, while other segments include articles on philosophy, culture, media, and sports, in a format that somewhat resembles the classical daily papers.

Al-Khandaq newspaper presents itself as a space “for confrontational press, rather than a postbox in which political messages are exchanged, as is the case of the local mainstream media scene.” For the newspaper, this means declaring a bias to convictions, not to political parties and agendas. “We have a bias towards what we believe is right; towards the option that we think would help us avoid further widening the rifts and deepening the crisis," Lakkis concludes

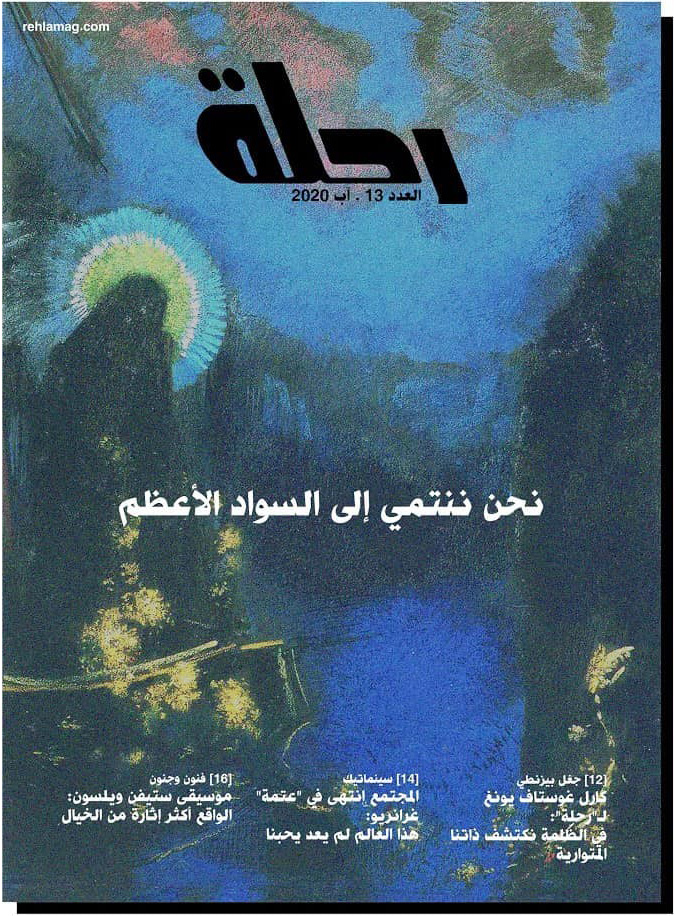

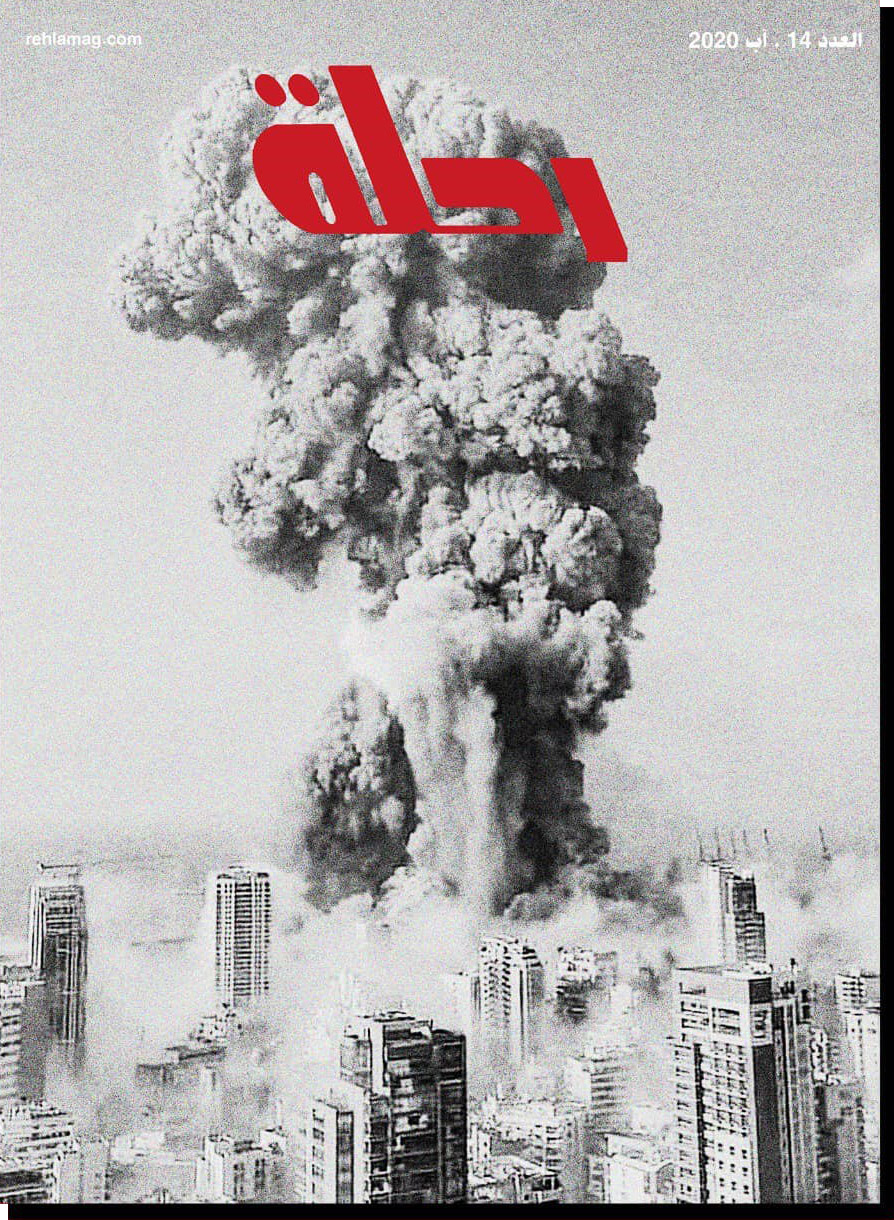

“Rehla”

“Experimental, underground, free” is how Rehla (meaning “Journey”) magazine (4) succinctly defines itself. The magazine is a distinctive experiment in terms of its non-generic language and its tendency to experiment with both form and content. Starting off as a sporadically published pamphlet made by a group of friends, Rehla predates the October 17 uprising. However, the protests in 2019 prompted the revival of the project that had been halted for a while; this time with greater editorial seriousness and at a steady monthly pace. Rehla’s editor-in-chief, Haramoun Hamieh, tells Assafir al-Arabi that “October 17 was an exceptional moment and an opportunity for us to get together as friends, but also as a group of people, each of whom is directly concerned with what’s been going on in the streets. The people of the October uprising tried to say that our problems and dreams were collective. We, too, believe that our individual problems are not so individual, as they have causes in the public sphere. So, we deemed it more useful to think and write together…”

On their self-introductory page, Rehla’s statement begins with a quote by writer Christina Engela, “If you don't do politics- trust me- politics will do you.” Their “journey” is a ride in the amusement park of politics, as they put it, “and in order to imagine Sisyphus happy, we must first pave the way and make sure that the trip happens..." It is a journey that’s been founded on a zero-budget, zero-cost base, as the founders have agreed that money must not be a detrimental issue for the continuity of publishing. With the work being fully voluntary, and with a little pitching in among the staff of friends, monthly issues could be sustained. Rehla has also recently launched a crowdfunding page on Patreon.

Each issue of Rehla has a chosen theme: darkness, alienation, nostalgia, dystopia, and other key words pop up. The articles touch on philosophy, poetry, cinema, architecture and politics in the broad intellectual sense of the word, as there is no news analysis or coverage of the mainstream sort in the magazine’s material. Rehla also publishes a monthly video essay (created and edited by Ali J. Dalloul ) (5), which has become a popular staple of the magazine.

Hamieh says Rehla is constantly trying to rebel against the algorithms of Google and social media websites. It aims to shatter the walls between writers and readers by working as a “slow media” which targets loyal readers who feel truly involved and interested in the project, and would thus seek it needless of the medium of advertisement. But what is it that makes Rehla tempting enough to be sought after? According to Hamieh, even independent Arab media platforms rely on funders who impose one or another kind of red lines, and most-recently, many of those boundaries have to do with political correctness. “While we realize the need of these platforms for funds in order to realistically function under their circumstances, we at Rehla are doing our best not to fall into that pit. It’s a trap because sometimes you lose the privilege of writing with absolute frankness. It is assumed that people won’t be widely accepting of non-popular opinion in the mainstream, although the primary role of the “alternative” media is supposed to be the advancement of an “alternative viewpoint” which challenges predominant narratives. Unfortunately, even “the alternative” has often become linked to supply and demand,” he concludes.

2) The parallel social media

Naturally, the media was also active online, as many pages appeared on social media platforms; namely Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Those pages shared news about the latest updates from the streets, announced rallies and called people to join protests, did live online coverage, posted the names of the arrested protestors, shared the latest developments about the banks, supported citizens in demanding their withheld money, and announced the statements of the different revolutionary groups. Some of these groups are: Shabab el-Masref (6) , Al-Saha News, Nationalize the Banks group (7), Kafih page, Lebanon is Uprising page, among others. At the peak of the demonstrations, these pages were transformed into primary, rather than secondary, news sources, which were more reliable at times than the mainstream media reports. Their content was continuously fed by news, photos, and videos from activists and protestors themselves, comprising a large number of photos and videos straight from the field.

Other online media pages focused on specific causes, such as the page “Save Bisri Valley” (8), which campaigned against the Bisri dam project, citing grave environmental and cultural ramifications to it, and explaining that while the project would destroy a biodiverse valley with money borrowed from the IMF, it was still bound to fail in solving the water problem.

Among the emerging groups, several represented alternative unions such as the Alternative Journalists Syndicate. Those fresh unions became increasingly familiar to the Lebanese as the protest movement progressed. Despite the absence of wholesome organization in the uprising, the online social media pages, albeit random and dissimilar, became widespread in cyberspace, bypassing all mainstream channels and democratizing, sourcing and accessing information.

Lebanon: A Special Type of Rent

13-12-2020

Naturally, in a situation characterized by social unrest and accompanied by state violence against demonstrators, countless rumors and inaccurate or fake news are bound to seep through. The numerous online media pages that popped up with the movement may have played a double role, providing much alternative content that may or may not be accurate, but also allowing the public to compare and scrutinize news from multiple sources.

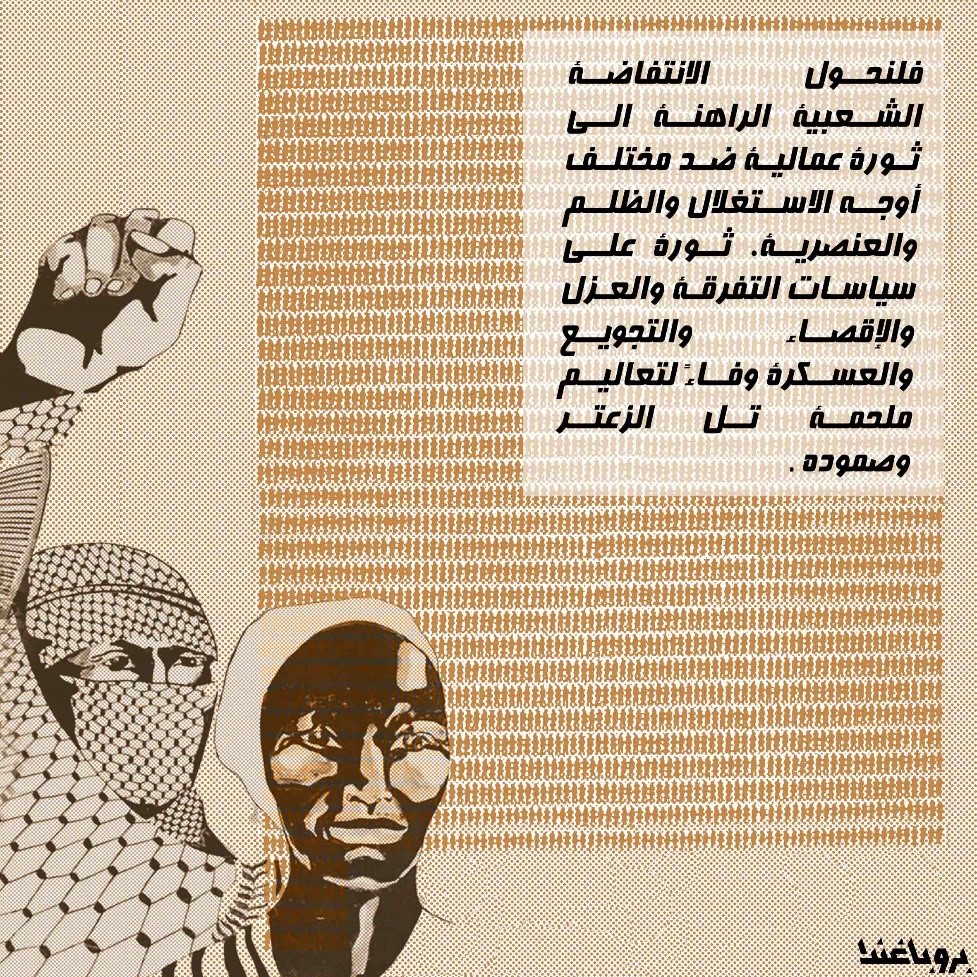

“Propaganda”: the media as a tool for incitation

One of the social media pages that chose not to report news was “Propaganda”, which instead claimed the slogan “Analyze, Incite, Organize,” as it unequivocally declares its encouragement of direct political action. Propaganda’s team tells Assafir al-Arabi that “the online formula for Propaganda may have crystallized after the 2019 uprising, however, this agitating platform is an extension of a much older, deep-rooted left-wing liberation movement, implanted in the first uprisings of the peoples of the region against the successive colonizers that have tried to take hold over this geographic area, leading to the establishment of the region’s state entities with their repressive, bourgeois, and proxy political regimes.”

The team explains that the name “Propaganda” fully expresses the scope of their work as a politicized media platform which has no interest in reporting news in a neutral way, as the platform seeks to analyze events and urge the working class to organize in confronting capitalist power. According to the team, Lebanon “is not a series of events and misfortunes, but rather an arena for conflicting narratives which grapple in the disparities amongst the waves of popular anger and the will to engage in a popular, autonomous class organization.”

Propaganda’s pages on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram share posters in which illustrations, photographs and texts serve the purpose of declaring a political stance and calling for action. The page also intermittently publishes narrated videos in which the voice-over builds an analysis or urges people to act, based on the presented data, footage, and archival bits related to certain realities.

Amidst the cataclysmic and frustrating political/economic climate in the country, Propaganda’s team believes that their platform was born not out of the need to address any momentary, circumstantial issues, but as a crystallization of the political ideology of Marxist internationalism which the team adheres to. “Establishing a media platform is not our end goal, but merely a tool which allows us to forward our endeavors to build a revolutionary organization,” they say. “Placing Lebanon in the context of global politics, we believe the effectiveness of our media platform is linked to the dynamics of this ideological current which has become more effective in the global political scene than it has been in the past few decades,” says Propaganda, whose team operates entirely on a voluntary basis.

Propaganda’s team describe their work as such: “We carry out this process of ideological deconstruction / analysis through engaging with the working class in direct action on the ground. For us, the role of the media does not end with reporting the news, but rather starts from it and evolves towards a systematic analysis which not only sides with the people in their suffering, but also strives for organizing strategies in the process of liberation from those systems which consistently reproduce that suffering”. Hence, their approach consists in playing the role of the antithesis to the ruling class and regime, rather than just another opposition group. “This process requires the removal of the popular movement from the immediate narrow demands (to the wider contexts),” the team adds. Hence, Propaganda’s posts address everything from feminist, socialist, classist, and workers’ struggles against the bourgeoisie, the capitalist neoliberal systems, and colonialism - not only in Lebanon, but in the Arab region and the rest of the world.

Conclusion

This essay naturally falls short of encompassing the wide range of media, cultural, and creative initiatives that were born out of the stimulating moment of the October 17, 2019 uprising and its subsequent protest movements. However, the text tried to sketch out a rough anthology of media and press projects/practices that have emerged during that exceptional period. The discussed experiences are indicative of the breadth of those initiatives, which are all largely distinct in their objectives, results and methods, and can even fall on polar opposites when it comes to their theoretical bases and political drives. Some of them might find meeting points with other groups, while others might find themselves on entirely parallel paths, but they are all liable to judgement by the people and the protestors (themselves a diverse group). The people have the liberty to agree, find nuances, critique, and disagree with these platforms’ rhetoric, without necessarily breaking the uprising’s togetherness. Such pitfalls can be avoided if the protesting groups remain attentive to the dangers of reproducing the old patterns of the polarized mainstream media or falling into the pits of ineffective exhibitionism.

The importance of these new spaces for expression, in all their asymmetries, is that they reveal traces of life; a pulsating core in a country which has had more than its fair share of calamities on every front, to the point that its stagnation has been mistaken for lifelessness. The problems are many: rampant corruption in the power relations between the media, money and politicians, capital and its domination of the cultural scenes, the bourgeois art spaces which alienate the popular classes, workers and students, the cultural hegemony of the center (the capital, Beirut) and the exclusion of the marginalized peripheries from most developmental projects over the years… In the midst of all these shackles, the only available spaces for the youth to engage in have most recently been related to NGOs and funds from foreign bodies, which appear out of nowhere and claim to give the youth a voice, a greater margin of freedom, and “modern” ways of expression. This is the world into which the new initiatives have stepped.

Taking all of the above into consideration, and adding to it the ripples caused by the movements in the streets of Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon, Nabatiyeh and other Lebanese regions, the inevitability of the emergence of a large number of diverse initiatives that took it upon themselves to open up new fields of expression- becomes clear, especially in the absence of a coherent vision or of multiple serious revolutionary projects that could keep up with the spontaneous nature of the insurgence and its accelerating events.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 11/12/2020

1)Dajani, N. 2019. The Media in Lebanon. Fragmentation and Conflict in the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

2) The website of the “October 17” paper: https://17teshreen.com/

3) Al Khandaq’s website: http://al-khandak.com/

4) Rehla’s website: https://www.rehlamag.com/

Video essay of the 11th issue of Rehla. Edited by Ali Dalloul. Source: Rehla

5) https://www.facebook.com/155417794618528/videos/598692754334188

6) https://www.facebook.com/msmasref

7) https://www.facebook.com/ta2mimalmasaref

8) https://www.facebook.com/savebisri