This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

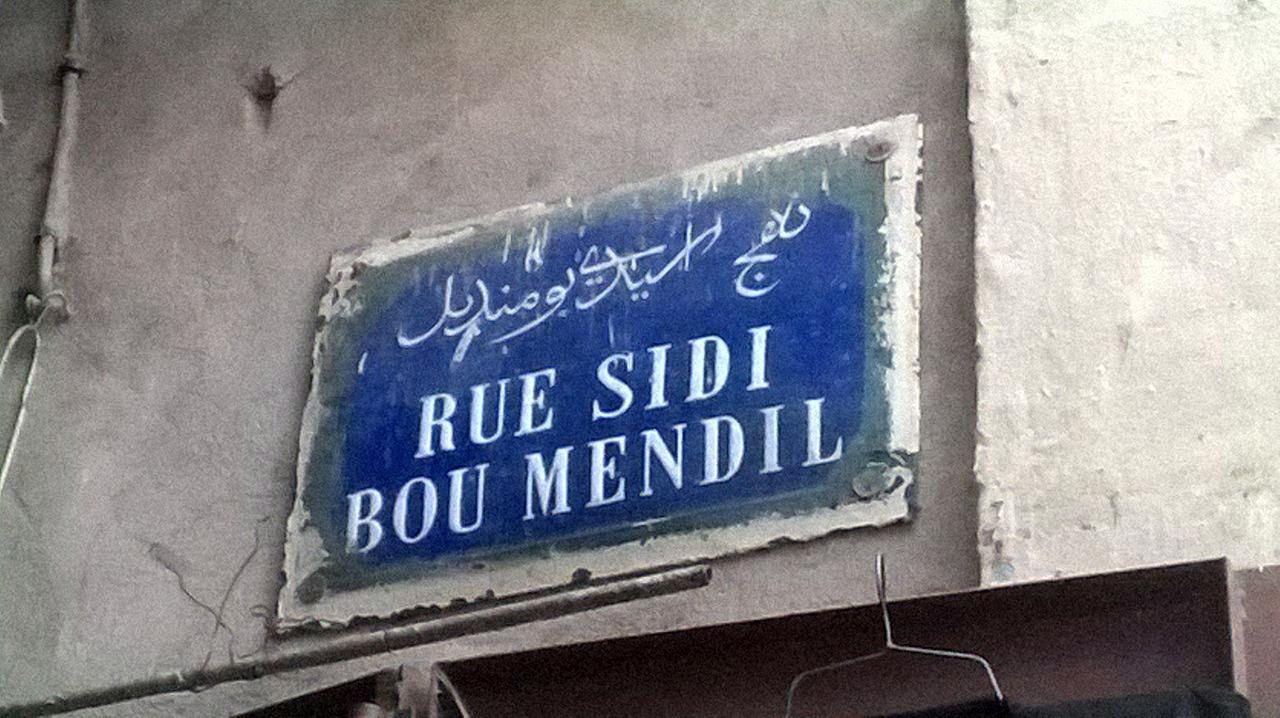

The popular souk in the Boumendil district, one of Tunisia's largest markets, is significant not only as a center for “parallel” trade, but also as a central market located in the very heart of the Tunisian capital, close to the government’s headquarters at El-Casbah and Habib Bourguiba Street. The Sidi Boumendil market is a bunch of interconnected alleys packed with shops and goods sold on the streets’ corners. It is a place where “citizenship” is exercised in the special ways of the “people of the margins”, right under the noses of authorities. The market - with its hawkers, permanent pavement stalls, shops and stores - extends from the "Sidi El Bshir" square to the "Barzali” square. Although business may be conducted differently depending on each merchant, most of them make their living in ways which do not comply with the official regulations.

Thirty years ago, the Boumendil market did not contained more than six shops that all sold spices and condiments. Today, it is packed with hundreds of traders who come, mostly, from the Tunisian inlands which have been neglected by the successive governments for decades. They are easily recognized by their distinct local dialects when calling on their goods in their high-pitched voices that have been echoing in all corners of the market since the 1990s. That was when migrants from “Jelmah” began to flock to Boumendil, individually and collectively, carrying the goods they had smuggled with the protection and complicity of officials related to the head of the regime.

In the Beginning was “Jelmah”

Jelmah is an agricultural area in the Sidi Bouzid province in the center of Tunisia. According to the Regional Development Index, the province ranks 20th nationally.

And, as per the results of the first phase of the five-point Development Plan for the period between 2016 and 2020, ten of its administrative districts (among the 13 present in the Sidi Bouzid province) rank between 217th and 258th of the state’s districts.

The agricultural nature of the region, the absence of an infrastructure that connects the different areas of the province and the declining conditions of facilities and services all prompted the inhabitants of the Sidi Bouzid province and of Jelmah in particular to get involved in smuggling activities with the “Trabelsia” family.

The relationship between one of Jelmah’s sons and the brother-in-law of the deposed president was sufficient to form a cohesive network of smugglers, merchants and street peddlers. Members of the network rely on family kinship. A significant part of them are from the "Awlad Khelfa" tribe. Family ties facilitate the mobilization of a large numbers of people and establishing a wider presence between the border areas and the capital’s markets: “What is bonded by blood cannot be divided by the hardships of the “contra*” (*smuggling)!” Children inherit from their parents the “trade secrets” and the mechanisms to circumvent any potential dangers. They memorize the terms that refer to "smuggling" and the methods, routes and systems of relations between the different actors in the trafficking network, until they know them like the back of their hands.

The experiences of the young people of Jelmah and Sidi Bouzid within the Boumendil market and its surroundings usually begin during their junior high school years, when they come to the capital seeking jobs during holidays and weekends. However, they continue to work in the market beyond their university years when they don’t find an employment.

In fact, a study conducted by the International Labor Office (ILO) revealed that more than 75 percent of young Tunisians aged between 15 and 29 work in the parallel economy.

The Octopus Extends its Tentacles… Beyond the Market

Many of the Boumendil young merchants are “small smugglers” who are “newbies” in the market. They take advantage of kinship relations to acquire goods from suppliers and sell them in the small shops and pavement stalls. Their suppliers may be their own brothers, cousins or friends, and the little traders usually only pay them once their goods have been sold. When the products go through customs control, they reach the market easily, however, “true kinship” among members of the same tribe is really tested when they have to cooperate to smuggle goods through land borders and into the markets.

The “small smugglers" devise new innovative ways every day to move their goods across the borders with Libya and Algeria, either in their own cars, mass transportation vehicles or small pickup trucks. If they are stopped by a patrol, they either pay a "fee” to the patrol members (5 to 10 dinars) or see their goods confiscated and fined. Security also often ignores the smuggled goods of the little traffickers in exchange for information they might provide about terrorist activities. On the other hand, a number of employees in the security service take advantage of their colleagues to partake, themselves, in smuggling activities, transferring illegal goods in their own cars across borders.

Poor students and low-income workers do not miss a chance to join the "small traffickers" often to smuggle cigarettes, electronics, clothes and shisha tobacco in their personal bags while traveling on buses or public vehicles. These means of transportation are only inspected in the rare cases of an emergency and, because of the obvious precarious financial situation of those small smugglers, the security guards would probably overlook their bags anyway.

Many of the goods that spread all over the Boumendil market enter Tunisia formally, with legal permissions through the ports, but then, their direction is “diverted” from the official markets to parallel routes.

After selling the goods, hawkers and street vendors in Boumendil share the profits directly with their suppliers. The owners of the stores receive shares of the profits proportionate to the efforts they made to acquire the containers coming through the ports or to extract the goods that trucks carry through land borders. Brokers who facilitate the arrival and removal of containers, including customs officers, security officials and influential politicians, also receive large commissions.

The major merchants of Boumendil acquire goods from senior smugglers, or the so-called “barons”. Under the command of the latter, night convoys travel with the goods, mostly under the protection of private security networks. These convoys operate in what they call “the searchlight style”: a car loaded with cash drives in the lead, while the others, heavily loaded with goods (electronic devices, cigarettes, gasoline, etc.), follow. The “searchlight” (el-kashaf) bribes the security patrols and, if they accept the payment, the rest of the cars are motioned to continue. However, if a patrol refuses to take the money, the rest of the convoy would quickly disappear out of sight and wait for another patrol to take over.

According to a report by the World Bank, there is a steady increase in informal trade activities along large parts of the Tunisian borders with Libya and Algeria. The report indicates that transport costs around 200 Tunisian Dinars for a truckload (about a ton) of normal goods, and that it could reach up to 1000 Dinars for more sensitive products. In the past, tobacco and alcohol were the most lucrative commodities, but smuggling has now become a gateway for arms and drugs. Many of these goods journey through dangerous routes to finally arrive to the capital’s markets, such as Boumendil.

Nothing has Changed After the Revolution

In the early years after the revolution, the Boumendil Souk, like many other popular markets, experienced a decline in its activities as suppliers ceased to operate and containers were blocked for weeks - or months - at different ports. In a letter to the Prime Minister of the transitional government (7 March - 23 October, 2011) Beji Caid el-Sebsi, Al-Moncef Bey and Al-Sabbaghin, merchants of Boumedil, wrote that more than 10 thousand Tunisians were negatively affected by the disruption of their families’ businesses in markets that contain more than two thousand stores. They also acknowledged in their letter that more than ten people used to share a single container of goods and that their work was facilitated by intermediaries from the "Trabelsia" family.

The interruption of the smuggling by land and the containers’ standstill in ports did not last long. The “Trabelsia” were replaced by other families, or, as the Tunisians would sarcastically comment, "there goes Ben Ali and here come the forty thieves!". The merchants of Boumendil are but the weakest link in a complex network that functions like an “octopus”, is run by the "barons" and overlooked by the authorities. Whenever the municipal police raid the market, it is the owners of the pavement stalls whose goods are confiscated first. Unless they are able to escape, they are subject to prosecution. Meanwhile, the owners of the regular shops are safe, although their goods come from the same sources and are often not credited by formal bills.

The young Boumendil merchants feel alienated in the new urban space. They are the newcomers rejected by the old merchants of the souk and antagonized by the young people of the surrounding neighborhoods who claim that these newcomers "stole their daily bread”. They carry a double stigma: They are known as those who come from the inner marginal cities, and they are also the "Canatriyyah" (contra-men/smugglers).

Not only smuggled goods are sold at Boumendil. Many of the products in the market had actually entered Tunisia officially with legal permissions through the ports, but then, they “diverted” from the official markets to parallel routes. Other Tunisian goods also leave the factories where they have been manufactured and head to parallel markets like Boumendil and others to be sold for at least half of their original prices.

According to the economist Mustafa el-Jwaili, these operations are carried under political and security protection. For example, two years ago, at the port of Halq el-Wadi, officials were surprised to find a malfunction in the surveillance cameras, especially in those monitoring the port's main gates. The administration demanded that the company in charge of the cameras secures the control cables by installing them inside the walls, but, soon enough, a tractor hit the main wall provoking its collapse! Those who know the parallel markets’ business confirm that many goods leave the port to destinations other than their initial ones, while containers carrying unauthorized goods keep on arriving to the port.

Security forces, municipal guards and policemen mobilize to track down street vendors and merchants of the popular markets, accusing the "Canatriyyah" (Contra-men) of transgression and monopolizing. Meanwhile, the senior smugglers take advantage of their relations with politicians or high-ranking officials in the Ministries of Interior, Economy and others to accumulate wealth safely, unfearful of persecution.

Unclear Boundaries

The phenomenons of smuggling and parallel trade were not an outcome of the revolution nor of the loosening of security after January 14th, 2011.

The smuggling of various consumer goods, such as foodstuff, electronic appliances and gasoline, has always happened right before the eyes of the Tunisian authorities. This is primarily due to the involvement of the sons-in-law and some members of the entourage of the deposed president who provided logistical facilitations, acquired goods and even protected smugglers from legal prosecution. They exploited their influence and the corruption of the customs apparatus in return for profits.

Secondly, these activities have always been overlooked because, in the absence of real and effective development policies, they provide a livelihood for a large number of residents of the inlands.

Moreover, there are no clear borders in Tunisia between formal and informal economies. For example, chemicals, lead and copper are smuggled into the country and redirected into organized economic routes after being purchased by licensed industrial companies.

The members of the Ben Ali and the Trabelsia families secured, in their own names, exporting permits for their entourage and accomplices. These permits are intended to be used by either them or others in their names, in return for commissions that compensate the customs tax. The parallel economy has contributed in creating black markets, such as Boumendil, that display the unregulated and untaxed goods smuggled by the Trabelsia family.

The Inevitable Margins

One of the paradoxes revealed by the phenomenon of smuggling is the reality of the Boumendil traders.

The sons of Jelmah fled from the misery of their marginal inland areas and arrived to the market looking for a living, with a desire to participate in the economic activities of the society. But the market, like a mousetrap, closed in on them. They found themselves trapped inside another “margin”; only this time it is an urban, harsher one.

Boumendil merchants live in constant fear of municipal police raids and the confiscation of their goods. Their greatest and most vital skill is thus their ability to collect their goods from the pavement and run like the wind when necessary.

The Boumendil merchants feel alienated in the new urban space. They are the newcomers rejected by the old merchants of the souk and antagonized by the young people of the surrounding neighborhoods who claim that these newcomers "stole their daily bread”. They are discerned by their local dialects when they call out on their goods. They also carry a double stigma: they are those who come from “behind the blocks” (from the inner cities), and they are also the "Canatriyyah" (contra-men/smugglers). These stigmatized sellers continue to refuse to integrate into urban society and often prefer to live with their peers within closed communities in specific neighborhoods.

The Boumendil traders who "rebelled" against the world of production - whether economic or symbolic in the form of a system of cultural values - are the most marginalized within the economic and social system and have become social outcasts . Apart from social stigmatization and the pejorative attitudes they endure, the Boumendil traders, especially those who do not own any shop, live in the constant fear of municipal police raids and the confiscation of their goods. Their greatest and most vital skill is therefore their ability to collect their goods from the pavement in a split second and run like the wind when necessary. This skill defines their competence to work and their ability to survive in the streets of the market that stretch like veins inside the body of the capital where the presence of security is abundant.

The owners of the shops selling billed and taxed Tunisian products do not forgive the pavement stalls, their inequitable competition and the attractiveness of their goods. The decline in the purchasing power of Tunisians contributed to the rising of the street trading. Tunisians of the middle and lower classes would rather buy a 350 ml bottle of a branded bottle of oil for 5.5 Dinars in the street, than paying 11.7 Dinars to buy the same product from a neighboring shop. It does not matter to the buyers whether the origins of this bottle are “unknown” or if it was exposed to the sunlight for long hours. What matters is that it satisfies their aesthetic preferences and saves them a few dinars.

Boumendil is an increasingly tense and stressful space inside which a sense of alienation is growing. It is a male-dominated space par excellence. The majority of the merchants in the souk are men while most of the shoppers are women who usually feel uncomfortable, fearing for their purses from the pickpockets and for their bodies from the harassers.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 31/05/2018