This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Brown land, a few cattle, and a sky that heeds the prayers for rain. These are the elements the Moroccan small farmer has or aspires to have. The land is the low-hanging fruit, a resource whose value is created through none other than plowing it and yielding its produce of grains, fruits, and the like. For centuries, agricultural land in Morocco has been the elixir of life, ensuring survival and sustenance. But it requires a lot, including legal documentation and registration, and more importantly, the provision of seeds, fertilizers, modern irrigation techniques, and other costs that are only affordable for the well-to-do or for those farmers who receive government subsidies which are mostly granted only to large, commercial farms.

Morocco is an agricultural country par excellence, with about 8.7 million hectares of arable land distributed over multiple sectors and holders, including state-owned and collective lands, as well as those owned by private sector companies and private investors. The country does not currently experience a severe food crisis, and Moroccans generally do not suffer from hunger. However, Morocco’s food security is threatened, as the country lacks self-sufficiency in several basic foods, such as grains and sugar (1). Meanwhile, Morocco is considered Europe's breadbasket; in other words, it meets the needs of European countries for agricultural products, and it exports half of its production of vegetables and fruits (especially greenhouse crops and citruses) to these countries.

During the colonial period in the first decades of the 20th century, Morocco was the French’s “fertile farm”. In the wake of its independence, Morocco tried to establish an agricultural policy as an emerging country preparing for an "agrarian reform" that would achieve self-sufficiency. However, it could not withstand for long in the face of domestic political and economic problems. Exacerbated by international pressures, those problems forced the country to comply with the preconditions for the commodification of the agricultural sector in favor of the foreign market and large commercial producers.

The land belongs to those who till it

“The land belongs to those who till it.” That was the revolutionary slogan adopted by the national parties in the 1960s for an agrarian reform aimed at reclaiming the lands seized by French colonists and establishing solidarity-based and cooperative farming. They coined this slogan based on the notion of equitably redistributing land to smallholder farmers. But the slogan remained a utopian dream which never came true. The state, represented by the Ministry of Agriculture, confiscated these lands from the French without distributing them in a way that benefited the small-peasant class.

Morocco: A Kingdom of Rent

18-04-2022

Generally, the independent Moroccan authority did not have a conclusive vision of the agrarian reform it wished to implement. However, it adopted agricultural experiments that began to bear fruit in practice, such as setting up land-reform cooperatives and collective plowing, or what is locally called Tweeza. In the 1960s, which were marked by increased nationalization and agrarian reform measures in developing countries (known as “third world” countries at the time), Morocco adopted a five-year plan, whose main slogan was "Agriculture First, Not Last." It planned to build dams and establish special commissions and directorates for farming and agriculture, such as the National Office of Irrigation, the National Office for Rural Modernization, the Agricultural Investment Offices, the regional directorates of agriculture, and others. These offices specialized in monitoring and managing this sector, serving as an executive body for the policies and directives of the state in its visions for agrarian reform.

After independence, the government’s schemes maintained the duality of its agricultural methods, both modern and traditional, preserving the interests of notables and large landlords while, at the same time, distributing lands to landless farmers in a way that fails to meet the results expected of agrarian reform.

In the second half of the 1960s, Morocco announced it would irrigate one million hectares by 2000. That royal decree aimed at managing water and facing climate change, especially recurrent drought. Also, the parliament passed a law for the reclamation of agricultural lands within the one million hectares irrigation project. The law aimed to obligate farmers to boost their production and to benefit from a system of grants and subsidies which motivates them to mechanize and modernize their farming practices.

The Moroccan state inherited modern agricultural organization methods from French colonialism and tried to apply them to large-scale farms, but it did not want to adopt them as a comprehensive system of interest for all farmers, big and small. That was because Morocco's agriculture imposed social norms (land inheritance, extended family style, etc.) and cultural norms represented in the tribes’ control over farming and irrigation system.

Like other developing countries, Morocco was then facing a historical challenge. Either it keeps pace with the modern patterns, including modernizing, mechanizing, and developing agriculture to benefit from its productive and profitable returns, or it maintains its traditional farming patterns. It is worth noting that traditional farming was a type of cultural practice rooted in the conscience of the small Moroccan farmer, who could not accept modern solutions because they were, in his view, “exotic fads” alien to his inherited patterns.

In that situation, the state urgently needed to rehabilitate traditional agriculture and develop the modern techniques learned from colonialism. In the face of the escalation of political conflicts and crises in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the ruling authority took advantage of these political struggles and social-class conflicts. Then, the state thought it was in its interest to distribute 50,000 hectares of the land recovered from foreign feudal lords to about 60,000 landless farmers. It was an attempt to form a class of “lucky” smallholder farmers with the aim of “enriching the poor without impoverishing the rich,” according to the description of sociologist Paul Bascon (2). This took place at a time when the country witnessed military coups that almost turned things upside down.

Somehow, it led to the failure of agrarian reform or the failure to implement it as required, or at least the inability to propose a vision and a societal project based on contracts between all parties regardless of political ideologies. The government’s schemes maintained the duality of its agricultural methods, both modern and traditional, preserving the interests of notables and large landlords while, at the same time, distributing lands to landless farmers in a way that fails to meet the results expected of agrarian reform.

Then came the structural adjustment

In the 1980s, the agricultural sector in Morocco suffered a “heart attack,” as described by the late King Hassan II, the ramifications of which on Morocco’s economy were resounding, as a large part of the economy depended on the agricultural sector which represented between 15% and 20% of GDP. The root cause of the crisis was the debts that amounted to a staggering $12 billion. So what is to be done?

Borrowing is the classic prescription of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which grants a loan in exchange for its ability to control, intervene, and monitor from afar the country's economic trends. From then on, Morocco entered a pivotal stage in the history of its agricultural sector. After recovering its lands from the French colonists during the 1960s and 1970s, neo-colonialism came seeping through the window. "Reducing governmental interference in economic affairs," including the agricultural sector, is one of those readymade IMF prescriptions. The state thereby gradually lifted its hand from this sector, allowing large private companies to replace it in taking control, and all doors were flung wide open for them to benefit from the capabilities of the state. As for the small and medium agri-producers, who were left vulnerable to the vagaries of the climate and the fluctuations in rainfall, the solution was to migrate towards the cities like other villagers who find themselves compelled to leave their bone-dry lands.

Debt reached $12 billion in the 1980s, and the IMF hand a readymade prescription. It grants a loan in exchange for its ability to control, intervene, and monitor from afar the country's economic trends. From then on, Morocco entered a pivotal stage in the history of its agricultural sector. After recovering its lands from the French colonists during the 1960s and 1970s, neo-colonialism came seeping through the window.

Based on the requirements of the IMF, the state gradually lifted its hand from the agricultural sector, allowing large private companies to replace it in taking control, and all doors were flung wide open for them to benefit from the capabilities of the state. As for the small and medium agri-producers, who were left vulnerable to the vagaries of the climate and the fluctuations in rainfall, the solution was to migrate towards the cities like other villagers who find themselves compelled to leave their bone-dry lands.

In the 1990s, Morocco took a second step in the same direction. It concluded extensive agreements with its EU and US partners within the framework of the Free Trade Agreement. That step turned the agricultural sector into a free market in which major companies and large commercial groups compete. At that stage, more emphasis was placed on commercial crops devoted to export. The goal was to meet the needs of the Western market, pay off the debt, and religiously implement the dictates of the IMF. “The IMF calls on each country to specialize in the production of its own distinctive local materials and to export them abroad to bring in hard currency that will enable it to purchase the required materials from the international market (3).”

These dictates have been the foundation of a new sector called commercial agriculture, or agribusiness. It controls all stages of the production process: modern plowing, germination, fertilization, harvesting, packaging, and, finally, exporting to foreign markets.

Although Morocco has adopted its agricultural policy as per the dictates of external powers, this policy has nevertheless helped move the local economic drive that depends mainly on agricultural production. It has also introduced unprecedented modern patterns in irrigation and related industries. But the question is whether these major companies have contributed to meeting the needs of the local market for food. In fact, they have in part; most of the vegetables and fruits in the local market come from medium-sized farms. As for large farms, they export their top quality products to foreign markets, leaving their poor quality products to the local market.

Fruitful land for large-scale commercial farms

Hundreds of hectares of green and fruitful lands stretch into the horizon. We can see them from far and near along the fertile plains that make up a considerable part of Morocco's northern, western, and central regions. But who owns them

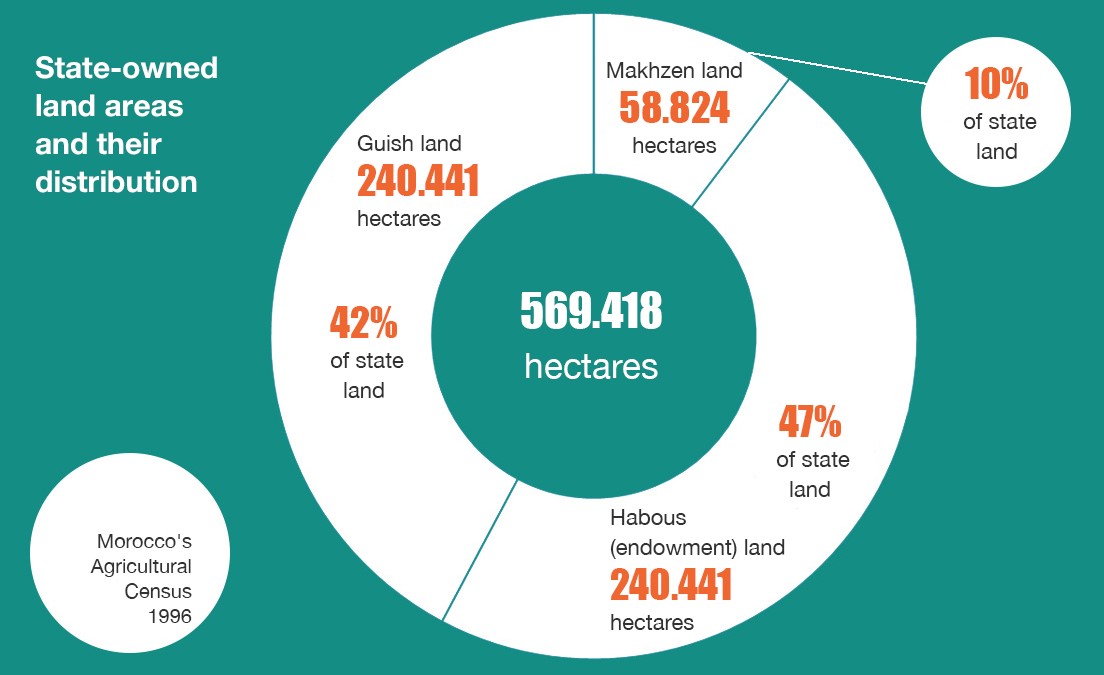

Most of Morocco's agricultural properties and lands are owned by large holder families with an extended and deep-rooted history of deals within a complex network of overlapping interests with Morocco's political elite. Until the mid-1990s, those families acquired 747,000 hectares of the land recovered from the French colonists. The state-owned land has shrunk over the years, decreasing from 491,000 hectares in 1981 to 238,000 in 1996, of which 132,000 hectares belong to the state-affiliated companies of SODEA and SOGETA, which were offered for privatization. They were either ceded under long-term lease contracts or sold through economic agreements with local or foreign investors. Sometimes, lands were also granted to political and influential figures as a kind of “gift”, “reward”, or bribe for their “services to the authority”.

According to a report by Morocco's National Authority for the Protection of Public Funds and Transparency, the area of land run by the two companies has shrunk from 305,000 hectares to 124,000 hectares. Moreover, the area of cultivated land does not exceed 99,000 hectares. Starting in 2006, the two companies relinquished their lands over two phases, relinquishing about 44,000 hectares in the first phase and about 38,000 hectares in the second. As part of the so-called agrarian reform, the two companies leased the remaining land lots at nominal prices for 99 years. Other land lots were “seized” by some influential figures, and others were granted to politicians and figures close to the government. According to the Authority's report, all the lands run by SODEA were ceded to private sector companies so that the company could "cover up the long-standing waste and embezzlement of the returns of the most fertile farms in the agricultural sector for many years."

Hundreds of hectares of green and fruitful lands stretch into the horizon. We can see them from far and near along the fertile plains that make up a considerable part of Morocco's northern, western, and central regions. Most of these agricultural lands are owned by large holder families with an extended and deep-rooted history of deals within a complex network of overlapping interests with Morocco's political elite.

More precisely, eight major companies have dominated Morocco's marketing and commercial agriculture sector, where Moroccan private sector companies own about 14,000 hectares. On the other hand, the French companies Azura and Soproville-Edel are investing in the cultivation of more than 2,500 hectares, which they acquired after the market liberalization policy was adopted by Morocco in the 1980s.

The large landlords and investors in agriculture have not been satisfied with the privilege of having vast agricultural lands. In fact, they pressured the state to obtain more concessions, such as benefiting from the tax exemption stipulated in the Green Morocco Plan, which Morocco adopted in 2008. Unions and human rights organizations leveled criticisms at those big producers because they imposed working conditions they described as “hard” and “inhumane.” Under the terms and conditions of employment, laborers work under fixed-term and seasonal contracts according to the productivity of the agricultural season. Their minimum agricultural wage, which does not exceed $180 per month, is much lower than wages in other sectors. In addition, the working conditions have deprived most workers of the services of the National Social Security Fund, a government institution for insurance and retirement. The workers registered in this insurance institution do not exceed 12% of the total workers (4).

Gulf investors are also seeking to own or rent agricultural lands in the most fertile areas in Morocco. The Director General of the Agricultural Development Agency announced that five to ten Gulf companies had participated in an international tender in Morocco to invest in cultivating 20,000 hectares of the state's most fertile agricultural land. According to the government official, Morocco will undertake a long-term lease. Tabuk Agricultural Development Company, a Saudi company, and Al-Qudra Holding, an Emirati company, as well as other investors from Bahrain and Qatar, are participating in the tender.

Eight major companies have taken over Morocco's marketing and commercial agriculture sector, in which Moroccan private sector companies own about 14,000 hectares. On the other hand, the French companies Azura and Soproville-Edel are investing in the cultivation of more than 2,500 hectares, which they acquired after Morocco adopted the market liberalization policy in the 1980s.

Morocco is looking to quadruple its land lease to foreign investors to reach 500,000 hectares by 2020 to "raise production and accelerate the modernization of the agricultural sector." Until 2014, Morocco had leased about 105,000 hectares of agricultural areas with capital and investments amounting to $3.5 billion. The government concluded half of those contracts with French, Spanish, and Italian investors, while the share of the Gulf countries did not exceed 3%. The government leased these lands for 20 to 50% of their market value under long-term contracts of up to 40 years. However, the government could expropriate these lands if the investors failed to fulfill the obligations stipulated in contracts and agreements.

Erratic rainfall for small farmers

The smallholder farmer's production depends on the fluctuations in rainfall, which has itself become scarce. Hence, Muhammad5, a farmer who lives in the town of Bin el-Ouidane, and other small farmers usually perform Istisqaa, an Islamic prayer asking Allah for rain. However, the irony is that the problem starts precisely when it rains, as it often rains erratically! Sometimes, when rain falls heavily for a few consecutive days, it causes soil degradation or infertility due to soil erosion. At the beginning of the current agricultural season, for example, it rained at a steady rate only in the first few months, just before the plowing process, which takes place in October and November. Then, rainfall gradually decreased in the following months, until it disappeared at the beginning of the current year 2019. The southern regions have remained the most damaged by the lack of rain. "Premature harvest" was the recurrent phrase uttered by every small southern farmer during the spring month of March 2019. The crop is wilted, its leaves are yellow, and there is no point of waiting for a few spring showers.

Water is a concern for the small farmer despite his limited land area. Muhammad, who owns only five hectares, his land is exposed to seasonal droughts from time to time. As for the dam's water, he does not benefit from it because he does not have enough money to acquire drip irrigation techniques that save 40 percent of water consumption.

According to Paul Bascon (6), a sociologist specialized in the rural Moroccan transformations, the policy of building dams, which the state adopted to collect and manage water for the purpose of developing agriculture, has gradually lost its "old nature as a strategic factor in arid and desert areas, because [the dams] have been placed under the disposal of the private sector companies in proportion to the area of land they possess. This can only reinforce the dominance of private land ownership within the social competition."

Muhammad's problems are not limited to the lack of money, but stem mainly from the lack of documentation of his agricultural property, unlike Abdul Rahim who was able to benefit from the support granted to small farmers who own land not exceeding five hectares to register their property per the preconditions set by the government. The authorities seem to be rushing to tackle the problems facing the land registry. In February 2019, the government issued amendments to the 1929 decree defining frameworks for “Al-Aradi al-Sulaliyya” (or tribal lands) to “solve the complex problems” associated with the tribal and family system. The Ministry of Interior also stated that it would implement the amendments and register those tribal lands with the real estate authorities.

The map of agricultural land distribution

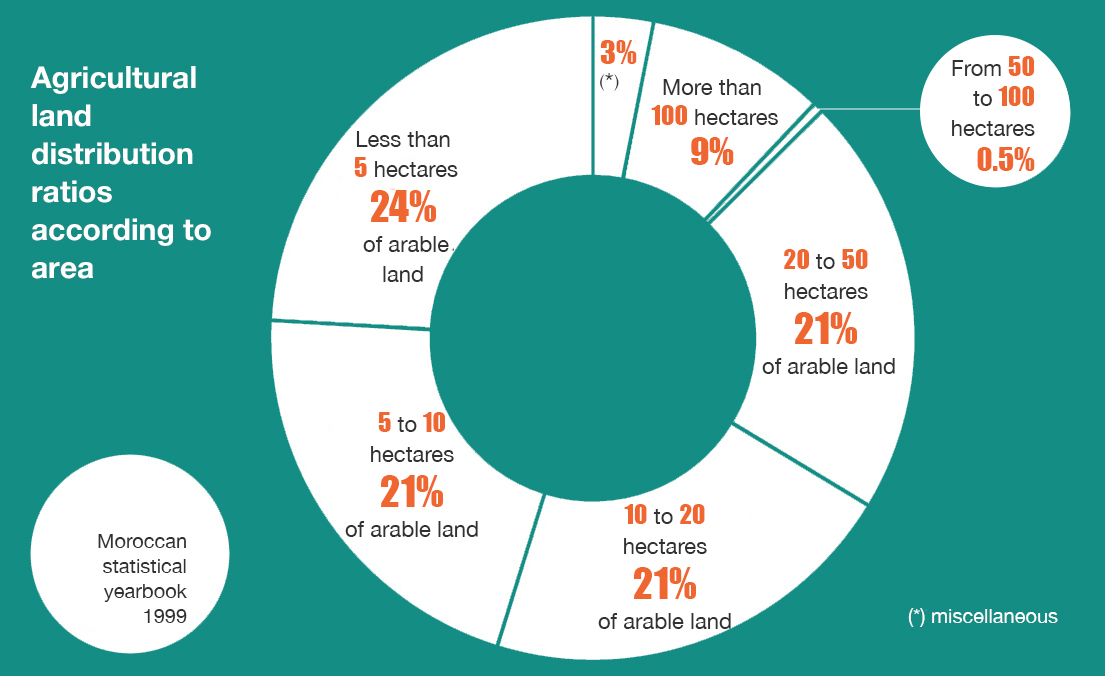

Most small-scale exploited lands belonging to smallholder farmers are susceptible to fragmentation due to the inheritance system, disputes, rural migration, and problems related to the scarcity of financial and natural resources necessary for the optimal use of these lands (7).

• land is the land the “Makhzen” (state) had originally given to some tribes to protect the nearby cities, granting them exploitation rights – without being able to own the land - in return for providing military services to the state, such as deterring the rebellious tribes that refuse to pay taxes to the treasury.

• (Habous) land is run by the Ministry of Endowments and Islamic Affairs. Its proceeds are allocated to charitable and religious services. Habous land - which is often donated by wealthy individuals, groups, or the Makhzen - cannot be sold. According to a census more recent than the 1996 census (8), the land covers an area of about 84,000 hectares and represents 1% of Morocco’s agricultural land.

• Makhzen land: The Makhzen is the ruling political and administrative body. The term is also popularly used in Morocco as a word meaning "State" or "Government".

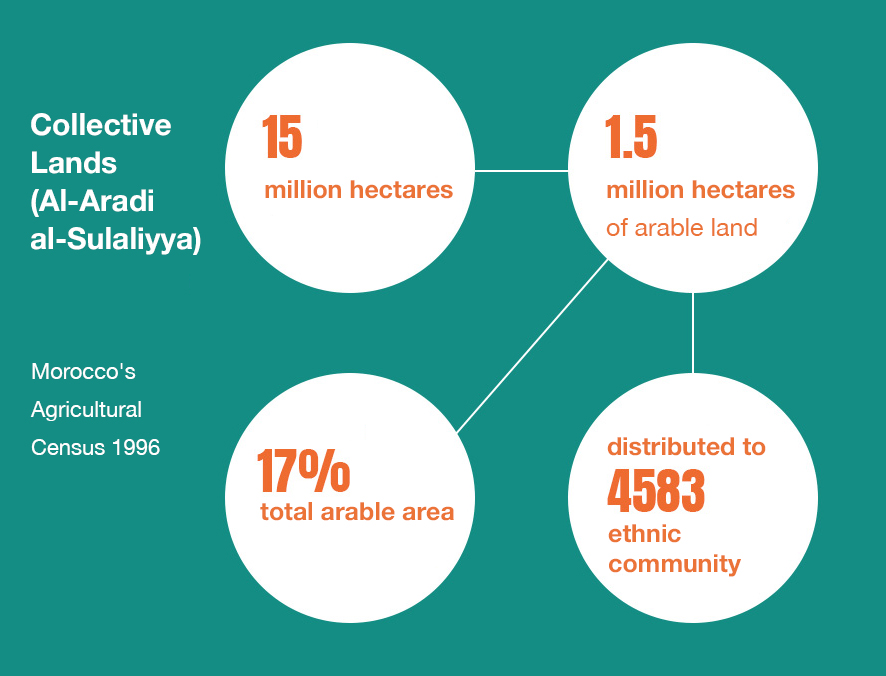

The total area of the Sulaliyya tribal lands is about 15 million hectares, distributed over 4,583 ethnic communities. It is run and accessed by principles established by local customary norms. Per the 1996 general census of the Ministry of Agriculture, its arable area is 1,544,696 hectares, representing 17.7% of Morocco's total arable area. Those lands are managed by the Royal Decree issued on April 27, 1929, which was amended in February 2019 to add provisions related to usufruct rights and its management. The decree also mentioned the possibility of ceding these lands to private sector and public (governmental) agencies to implement investment projects. Recently, the Ministry of Interior announced that 2019 would be the year for the census of those tribal lands and their documentation in the deeds registry.

Citrus fruits and greenhouse crops: Sous is the garden of European investments

Moroccan tomatoes arrive to the European consumer in fresh red, elegantly and attractively packaged. However, the devil is in the details. Most tomatoes are cultivated in the Sous region, distinguished by its mild and warm climate all year round, which allows tomatoes to grow fast with the quality required by EU standards. France is among the countries that invest heavily in such marketing crops through a company that owns 14 farms. They cover an area of about 400 hectares of greenhouses designed for producing cherry tomatoes with a volume of 37,000 tons for the European market. These lands are owned by one of the heirs of the big landowners in Morocco.

Activists and smallholders have accused this company and other investment companies in the agricultural marketing sector of draining tremendous water resources. Lehsein, a smallholder farmer from the Chtouka province of Sous, has explained that such large farms had drained the water bed by drilling 600-meter depth water wells with modern techniques. That made his small well, which does not exceed 60 meters in depth, vulnerable to running out of water.

“There’s nothing left for us,” Lehsein summed up the conditions of small farmers, who used to receive government subsidies before Morocco entered the stage of the imposed structural adjustment. Local farmers like him often find themselves caught between harsh economic realities: the high cost of living on the one hand and the absence of any guarantees for the continuity of their agricultural production on the other hand. According to Lehsein, they have no choice but to sell their livestock and lands if they’re lucky to find a buyer, or to otherwise abandon them and emigrate. In the worst-case scenario, they work on a farmland as wage earners under employers' terms, which do not comply with their minimum rights stipulated in the Labor Law. Lehsein, too, is about to leave everything behind if rain does not fall and save his land.

Production in Sous

-In 2013, the greenhouse crops amounted to 1,340,000 tons.

-The production of citruses in 2013 amounted to 893,000 tons (9).

National production (agricultural season 2016-2017)

-The volume of tomato exports amounted to 517,000 tons, worth $565 million. 78% of which was sold to the EU and 19% to Eastern European countries.

-The volume of greenhouse crops’ exports reached 1,881,000 tons, while the value of vegetable exports amounted to about $566 million.

What about Green Morocco?

Since 2008, Morocco has adopted the Green Morocco Plan, presented by the state as an ambitious project and one of Morocco’s economic drivers. The state asserts that the project has attracted huge investments and local and foreign capital, amounting to about $6.7 billion (according to the latest figures released by the Ministry of Agriculture in 2017). The Ministry of Agriculture sees that many achievements have been made in terms of the increase in the production of agricultural products such as greenhouse crops, citruses, and grains, which are generally suitable for export to EU countries.

The Green Morocco Plan aimed to develop agricultural growth under two pillars. The first is “strengthening and developing high-productivity agriculture that responds to market requirements by encouraging private investments and new models of the equitable collection.” The Ministry of Agriculture added that “it includes between 700 and 900 projects, representing about 110 to 150 billion dirhams (about $10.3 billion to about $14.1 billion) of investments over ten years.” The second pillar, per the Ministry of Agriculture, aspires to “fight poverty in rural areas by significantly increasing agricultural income in the most vulnerable areas." Under this pillar, 550 solidarity projects are expected to be completed, with an investment ranging between 15 and 20 billion dirhams (about $1.4 billion to about $1.8 billion) over ten years. In general, the Green Morocco Plan is financed by local governmental and semi-governmental bodies and institutions, as well as by foreign institutions such as the IMF and funds from the European Union.

According to critics, the Green Morocco Plan has not yet achieved self-sufficiency, that is, provided food security, nor has it even started to revitalize the economic in a way that could absorb unemployment in the countryside and cities. Moreover, it has focused only on production for export. It does not care about the deficit in basic foodstuffs that accumulate annually, which makes Morocco one of the largest importers of grains, oilseeds, and sugar in the Mediterranean region. In addition, the reality is that smallholders have not benefited from the outcomes of the Green Morocco Plan nor its subsidy because it is mainly intended for large landlords.

During presenting the current Finance Bill to Parliament, the Minister of Agriculture confirmed that his ministry had not excluded smallholders from the plan. He said that his ministry would distribute one million hectares to small farmers and included 156 new projects that would benefit 64,000 smallholders. In addition, the Ministry of Agriculture allocated projects related to olive chains. They included 191,000 beneficiaries and 238,000 livestock breeders, including red meat chains.

Furthermore, the number of solidarity projects allocated to smallholders in the last ten years reached 813, with investments estimated at $1.9 billion. Part of them was approved for restructuring of cooperatives with an area of 850,000 hectares.

According to critics, the Green Morocco Plan has not yet achieved self-sufficiency, that is, provided food security, nor has it even started to move the economic wheels to absorb unemployment in the countryside and cities. Moreover, it has focused only on production for export. It does not care about the deficit in basic foodstuffs that accumulate annually, which makes Morocco one of the largest importers of grains, oilseeds, and sugar in the Mediterranean region.

However, it seems that this government plan has been fraught with problems and pitfalls that economist Najib Aksabi has summarized in four points. The first is the plan's failure to create production independence due to the dependence of production on rain. “One of the main objectives of the Green Morocco Plan was to reduce the impact of dependence on climatic fluctuations and to secure a minimum level of independence to agricultural production. But this has not been achieved so far,” Aksabi said. The second pitfall lies in Morocco's failure to achieve self-sufficiency in vital food materials such as grains, sugar, and others, as "the quantity of imported grains remained unchanged." The third problem has to do with exports, as “the country has doubled its production of vegetables and fruits intended for export, but was unable to create new markets for the surplus," he explained. “The final pitfall is that the goal of creating 1.5 million jobs between 2008 and 2020 has not been met. On the contrary, official figures indicate that 150,000 jobs were lost between 2008 and 2017,” Aksabi added.

Furthermore, the Audit Court's annual report for 2018 stated that there had been a decline in the volume of irrigated areas, which ranged between 38% and 45% of the cultivated land. This volume does not comply with the provisions of the domestic agreements, which recommended watering 67% of it. On the other hand, the report referred to the remarkable "development" in producing durum wheat and barley. It stated that the area planted with both products had tripled. However, the Audit Court expressed doubts about the criteria and indicators adopted in setting the desired goals, whether in the domestic agreements or the Green Morocco Plan. In fact, it became clear to the Audit Court’s observers that there was a wide gap between the written goals and the practical achievements on the ground.

All in all..

Morocco's agricultural policies remain hostage to its commitments as a food basket of the land’s finest produce meant for the European and foreign consumer who takes priority over the local consumer.

Despite the construction of hundreds of dams throughout Morocco, rain remains the principal indicator for agricultural production. That, of course, does not affect the large landlords in the same severe manner it does small framers, with further losses or circumstantial gains dependent of climate fluctuations.

Economists and agricultural experts have unanimously agreed that Morocco can meet its staple food requirements by encouraging subsistence and rain-fed farming. However, the problem of how to structure, organize and document this type of land persists. That is because most subsistence and rain-fed lands are fragmented or neglected by their owners due to family issues, such as inheritance, or distribution according to tribal customary norms. In the end, the biggest challenge facing agriculture in Morocco, and other developing countries, is to secure food without dependency. Currently, this does not seem possible in the foreseeable future; the dictates of international financial institutions and the stipulations of agreements with foreign partners will have their say over the coming years. However, the state's political will can change the course of this situation by providing its citizens with their food baskets before meeting the requirements of the European market. In other words, the state has the power to decide not to allow the West to “have our cake and eat it”.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 01/04/2019

1- According to the statistics of the Ministry of Agriculture, 16 million tons of wheat were imported during the last four years, representing 39% of the country’s total need.

2- An interview with the sociologist Paul Bascon, conducted by Tahar bin Jelloun. It was published in the French newspaper Le Monde on January 24, 1979, and in the Moroccan Journal of Economics and Sociology in Morocco, double issue 155-156, 1986.

3- According to Moroccan economic and agricultural analyst Najib Aksabi.

4- The dilemma of the Moroccan agro-export model. Omar AZIKI (Secretary General of ATTAC/CADTM MOROCCO)

5- In Morocco, the drought took over the dam, report by Théa Ollivier, Libération.

6- Interview with sociologist Paul Bascon, previous reference.

7- Moroccan statistical yearbook 1999.

8- The statistical figure as mentioned in the book, The Rural Society: Questions of Deferred Development, by Moroccan sociologist Abdul Rahim al-Otari, p. 25, first edition 2009.

9- Statistics of the Moroccan Ministry of Agriculture.