This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

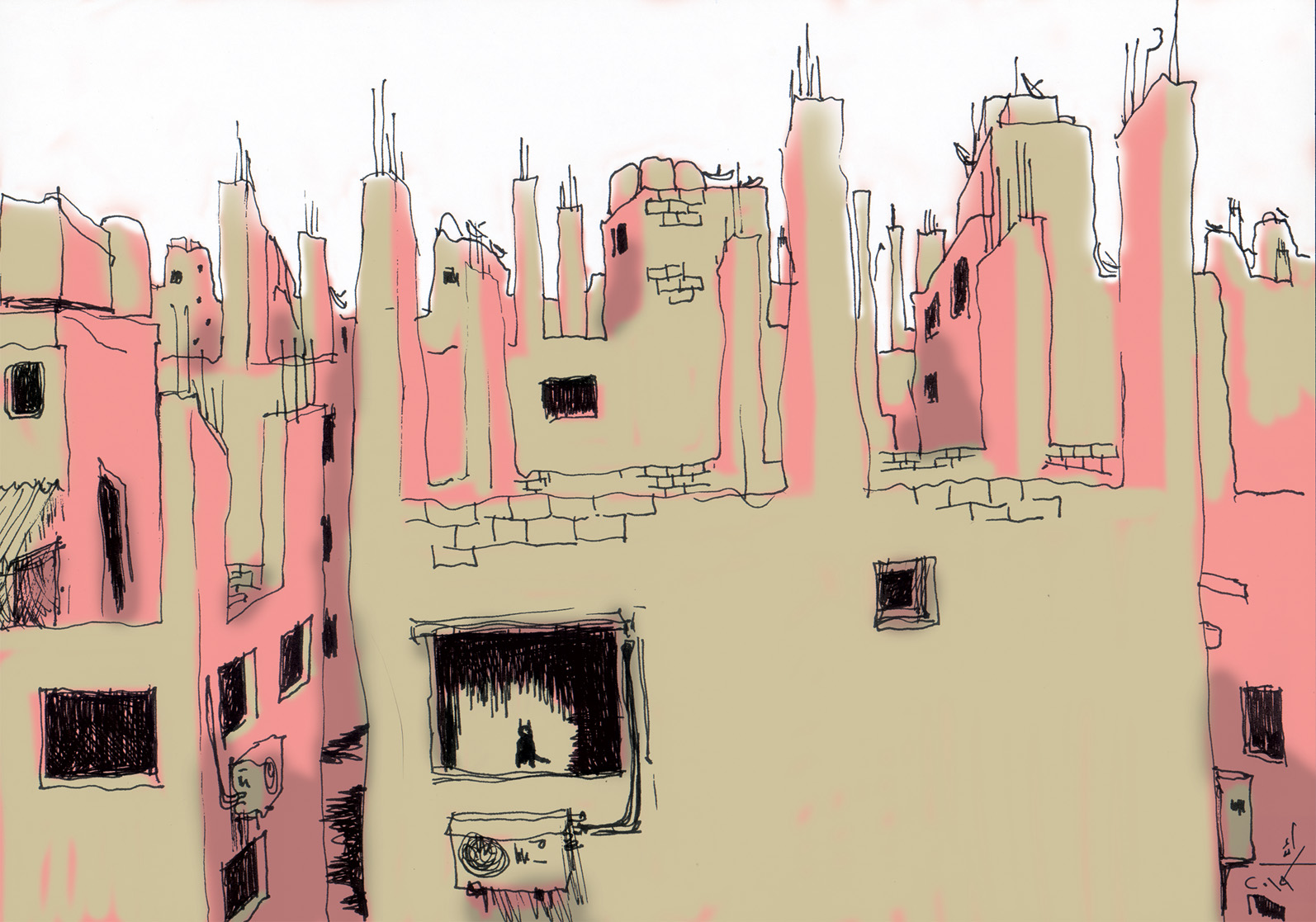

Shantytowns in Morocco are called “barariques”, derived from the French “baraques”, meaning tin shacks. This “undesirable landscape” is widely dubbed “khnouna” (meaning “snot”) in Moroccan Arabic, especially when those grey tin entities peep through the shimmering glass skyscrapers, or when a new tramway line penetrates it, passing pompously through an odd, incoherent scene which amalgams modern forms and improvised spaces.

These neighbourhoods’ populations didn’t choose to live in shantytowns. They didn’t ask for it, but were forced into it. Shantytowns began with the French and Spanish colonial era at the beginning of the twentieth century. The policy to take over rural lands and expropriate them (by hook or crook) pushed rural populations to migrate into the cities and their peripheries. Additionally, years of drought hailed in, along with disease and hunger. Tin boxes mushroomed near the factories (as happened in the Kariyan Central neighbourhood in Casablanca), and after independence, the situation aggravated as shantytowns spread into most cities. In the early 2000s the Moroccan authorities decided – publicly and strictly – to put an end to these shantytowns. However, the government’s “Zero Shantytown Project” would not be fully realised, with the government announcing its failure last year. It sufficed itself with the elimination of 59 shantytowns out of 85 (1).

Agadir’s morphology: An organized centre and an overcrowded periphery

Unlike most Moroccan cities, Agadir’s city centre wasn’t constructed in the classical manner, and it wasn’t a mix of modern and historic. The 1960 earthquake destroyed everything and levelled down every landmark in the city. Only the fragments of forgotten walls remained scattered here and there. “A blessing in disguise” is what some would say, arguing that the destructive earthquake can be a chance to build a new and modern city, with standards that comply with an organized distribution of neighbourhoods, essential facilities, and infrastructures. That process of construction, however, moved slowly; the city inhabitants feared a recurrence of the natural catastrophe, knowing that their city happens to be located by the biggest fault in North Africa (according to geologists).

Inezgane

With looming earthquakes in mind, locals headed to some suburbs and peripheries. Inezgane (with more than 130 thousand inhabitants) was one of them. At the beginning, it was no more than a small city under French colonial control. Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, it would transform into a concrete jungle, completely filled with shantytowns by the valley, out of the local authority’s sight.

The nascent city would be a hybrid formation of consecutive migrations due to years of drought that spread over Moroccan villages (in the early 1980s). Most inhabitants have hailed from the rural Sousse region (2), while the rest have hailed from several areas that include the western and south-eastern coastal cities as well as the southern regions of the desert.

“I’m not sure why God would create a city like Inezgane”, says a person who implicitly comments on the city’s reality and the chaos that characterizes it. The city welcomes visitors with the biggest taxi and bus station in southern Morocco, but is full of beggars, pickpockets, and (abandoned) street children; they are joined by people with mental disorders, often shunned by their families and without shelters or sanatoriums to accommodate their needs.

Like other inhabitants of nearby cities, Naima (3) barely manages to get out of one of the worn-out taxis (4), overcrowd with six passengers, for both shorter and longer trips.

Near the station, and all along the city’s main road, peddlers sell their goods, chanting out loud, right before religious holidays, rkha (which is street Moroccan for “cheap”) or rebaja (which means “discount” or “lowered prices” in Spanish).

The Inezgane margins (especially the neighbourhoods adjacent to the valley) pulled more inhabitants in for their low real estate prices. The local authorities equally ignored illegal construction in the 1970s and 1990s, with all the ensuing governmental negligence when it comes to providing essential services and facilities (schools, healthcare centres, public transportation…).

Space for pedestrians is practically nonexistent on the sidewalk. For Naima, Inezgane is a prime location to do one’s shopping for the week. It is the largest commercial centre in the Moroccan south (with more than 2652 stores) (5), and it offers local and imported goods (mostly from China) at reasonable prices. Chaos is the name of the game in this place, where parallel (unregulated) economic activity thrives through the notable presence of street vendors and independent craftsmen (plumbers, handymen, etc.) who live in neighbourhoods adjacent to the Sousse Valley.

Morocco: A Kingdom of Rent

18-04-2022

The "Gloomy" Economy of Morocco

15-07-2019

The margins of Inezgane (especially the neighbourhoods adjacent to the valley) have pulled in more inhabitants than other areas due to their low real estate prices. The local authorities equally ignored illegal construction in the 1970s and 1990s, with all the ensuing governmental negligence when it comes to providing essential services and facilities (schools, healthcare centres, public transportation…), as has happened in a neighbourhood adjacent to the valley, locally known as Dawwar al-Leil (the Night’s Roundabout). The name is no coincidence; rather, it describes the illegal practices that would be carried out under cover of darkness: illegal construction, widespread prostitution, and drug dealing. With the beginning of the third millennium, however, Inezgane neighbourhoods no longer lived by the rhythms of these “neighbourhoods of the night”. “Improvements” were made that slightly effaced some of the “shanty characteristics” but without completely eliminating them; by providing some basic and infrastructure services (sanitation, schools, transportation, and pathways…). Chaos is still present as an inappropriate residential morphology, as overcrowding, and asymmetric alleyways. This hybrid state may also be perceived in the inhabitants’ practices. One such example is that the rural heritage is still sometimes manifest in breeding a few herds of sheep or poultry, even after the urban cement invasion of the neighbourhood.

In general, marginal cities (Inezgane, Aït Melloul, Dachira), lurking right behind Agadir and its “brilliant” touristic façade, constitute a hybrid case, made with a little bit of randomness and spatial chaos. These traits are most apparent and striking in the city of Koléa.

Koléa

Neither village nor city. This is what one might infer at first glance of Koléa (25 km south of Agadir). Somewhere in between these two notions (6), this town was thus born, with mixed and complex socioeconomic and cultural characteristics, which cannot be categorised within a premade framework, as it combines distorted modern urban patterns and others that draw on a crumbling rural legacy.

Showing signs of development in the early 1990s, the city experienced a demographic upsurge with a development rate that is the highest in the Sousse Massa region (5.69 percent, according to the 2014 statistics). The number of inhabitants rose from around 40 thousand people in 2004 to double that number in just one decade – reaching more than 80 thousand people in 2014… And the numbers are still going strong!

The Koléa population came from several Moroccan areas, most of which are from adjacent or faraway villages, as well as from nearby town peripheries (Inezgane, Dachira, Aït Melloul, etc.).

Koléa (25 km south of Agadir) was born as a combination of distorted modern urban patterns and others that draw on a crumbling rural legacy. Its population has doubled, from around 40 thousand people in 2004 to more than 80 thousand people in 2014. The town was formed of the people who had migrated from nearby or faraway villages, as well as those who hailed from other adjacent urban peripheries.

Primary observations of the city entrance held much disapproval, especially among the users of the only main road. The latter isn’t well paved and is at the receiving end of a “surgical operation” (as the inhabitants describe it) every now and then; public construction projects are repeatedly carried out to integrate sanitation, which has yet to reach some alleyways and neighbourhoods, especially the marginal ones. Sheep herds are also seen around, in search of dry plant remains or cooked leftovers in the vacant lands close to that road. Carriages may equally be seen crowding cars and trucks, as reckless adolescent motorbikes compete over space with them, along with many passers-by along the dusty road and a few hitch-hikers under the scorching noon sun, waving their hands at any form of transportation for a ride. (7)

Capital controls lifestyles

In the wee small hours of the morning, Naima stands semi upright next to her colleagues, near a sign that indicates a bus stop. Her face visibly shows fear and tension after she had left her “mouse hole” (as she describes her home), piled amidst hundreds of sardine-packed residences. The women standing with Naima are not waiting for a bus, but for a small truck that drives them all, huddled together for half an hour, into the “ranches” (new agricultural areas or farms), which extend behind their city where they work as day labourers.

The factories in Aït Melloul city (7 kilometres from Koléa) on the one hand and the agricultural villages centralised in the rural zone on the other (Chtouka Aït Baha province) take in hundreds of working women who live in this city. With the beginning of the third millennium, demand for these women would rise more than ever. Most male workers see this phenomenon as a threat to their “manliness”, as women have become the main, or sometimes the only breadwinners in some households.

Unlike Naima, the main breadwinner in her family, who works all year long in factories, and temporarily and seasonally in villages, her husband Ahmad finds himself to be unemployed (usually working gigs). At first, he didn’t like it that his wife would leave in the early hours of the morning to return home at around midnight. With time, however, he would justify such a step by saying: “To live is a question, and the answer is to bring in money, and at any price”. His consent isn’t based on empowering women, but rather on capitalist conditions that necessitate a workforce comprising women.

Such a phenomenon is notable in most Moroccan peripheries and shantytowns. According to the High Commission of Planning statistics in 2014 on private sector users of factories, agricultural villages, and intermediate contractors, more than 86 percent of females in Koléa are workers, as opposed to 51 percent of males. Indeed, this is due to the prevalent social conditions (unemployment, social “precariousness”, and others).

The factories in the nearby Aït Melloul on the one hand and the rural domains in rural villages on the other took in hundreds of working women who live in Koléa. With the beginning of the third millennium, demand rose over these women workers. Men perceive this phenomenon as threatening to their “manhood”, as women became the main, if not the sole, breadwinners in numerous households.

Ahmad and Naima’s case is quite representative of the bulk of villagers who flocked into Koléa at the beginning (1990s) as a result of the drought that had drained their lands dry. At the time, migration into the city was practically the only solution. The new economic conditions impact the lifestyle patterns of individuals who have hailed from a rural social structure. The modern, chain production patterns of villages, and the ensuing urban-industrial production patterns in the peripheries of the cities, have constituted both an opportunity and a shock at once. It was an opportunity to exit the misery from which villagers suffered and a “cultural shock” because the modern economic system dictated every detail, on both cultural and social levels: women’s participation in the job market and in the management of household expenses, the younger generation’s tendency to assume open-mindedness in clothing, speech, behaviour, and so on…

A middle class on the hunt for concrete jungles

Koléa is home to state institutions and structures: the municipality, governmental administrations, as well as the Royal Moroccan Gendarmerie, which manages the inhabitants’ affairs. The problem, however, stems from the nonexistent management of such needs, especially when it comes to security – considered to be the number one demand shared by all inhabitants.

Daily life, however, isn’t entirely left for people to figure out on their own; it is partly regulated by the law, partly subjected to customary regulations, or left unregulated, outside these frameworks. One example would be the issue of sanitation networks, which is currently managed beyond the state institutions. The governmental body responsible for sanitation fails to play that role, whereby privately-owned tanks empty out the sanitation reservoirs and dump their liquids into empty lands near the wooded zone. As for transportation, on the other hand, the available public means of transportation are insufficient for the needs of all commuters, which is why residents seek alternatives in unofficial means of transportation, like private car rides…

“We’re not poor, miserable scum, as neighbouring cities see us,” says Kamal, a public-school teacher, in critique of the narrow and reductive perception of his city. He affirms that many employees and teachers inhabit the area. And indeed, Koléa is no longer a place for the low-income people to resort to, but also for public employees, like teachers and middle-income administrative employees (8).

Real estate has obscenely grown in adjacent cities, whereby those very groups could no longer afford to pay back the long term housing loans (with a timeline of 30 years sometimes), in addition to wishes to construct multiple floor buildings – that is, a separate house with several floors, which enables rental investments in some of those floors – like medium or small sized apartments, as well as the ability to rent out a garage in the ground floor, for artisans, craftsmen, or businessmen. In parallel, local authorities sometimes look the other way on administrative conditions related to compulsory building and planning licences in faraway marginal neighbourhoods, making use of a relative drop in land prices (in comparison to surrounding cities), especially those that belong to the “Housing Cooperatives” (9), in an easier manner than bank loans, with the ability to purchase construction materials and pay for them in instalments.

The average employee usually prefers to own a house rather than rent one, even if it is a small apartment (10), a “tomb for the living” (as Moroccans describe it).

Kamal has also been trying to own a house with several floors (even if with a small area), as it enables him to expand vertically and invest in the ground floor (by turning it into a small housing unit and a garage for rent). Despite his education and urbanism, he was still holding onto rural patterns inherited from his parents; he looks forward to having a big family, rather than a nuclear one as is customary among the modern western families. His economic state, however (financial income and the ensuing necessities) force him to suffice with having two or three kids at most.

Young people in search of lost roles

“I choose this hairstyle so that I don’t look like I’m a coward and a poor guy”, was what young adults (between the ages of 15 and 23) would usually say to justify adopting a lifestyle that has become common among them, but alien in the eyes of their micro community (the neighbourhood and city).

Jamal is a young man around twenty years old. He is one of the “Koléa” guys who make up 26.5 percent (11) of the population. He carefully maintains the haircut that most of his neighbourhood inhabitants have adopted: a shaved head on the sides with a little bit of hair that slides into the back. Ripped jeans and a dark coloured t-shirt, and of course his “life companion” (hidden in his pants) the long knife, which he would never give up. As such, a twenty-year old young man tries, like the rest of the young men in his city, to assume “delinquency” (against the customary morality).

Barely a day goes by without hearing of a new crime, an offence, or a robbery assault. The inhabitants are aware that a security approach alone cannot suffice, as appropriate social services and conditions must also be provided to pave the way for a dignified life without marginalization or “huqra” (contempt). Being subjected to “huqra” fuels the youth’s desire to join worlds of violence, as they seek to prove their “masculinity” by joining a gang.

This group of young men seeks to fill in for the missing social roles in their communities. The lack in some roles is usually due to the profound shock that had hit the social structure, disrupting the former hierarchy and the values that enveloped it. Their disintegration stems from being rapidly uprooted from their places of origin. Such a shift wasn’t accompanied by any kind of stability either, whether in work or housing -regardless of how miserable those may be - but would be characterized by a precarious state of “barely getting by”.

Currently a resident of the city to which he hailed from the village, Jamal adopted this lifestyle as a defence mechanism against his micro milieu, following an adolescence full of bullying, verbal and economic violence from his neighbourhood and school companions as he appears and behaves like a “naïve” villager, or to avoid being called a “damdouma” (a coward and a poor guy). The young man tries to dissociate from his rural or even familial legacy in terms of morals and behaviour, while rebelling against the family and institutional authority (the state, the school, the police…), and to look for his alleged “masculinity” and “manliness” by belonging to a group (cliqua, an alteration of the French “clique”) or to gangs that steal and even rape, with their members enjoying common hobbies, such as additions to alcohols and bad hashish.

Barely a day goes by without hearing of a new crime, an offence, or a robbery assault, some of which leave people with permanent disabilities. The security question among the population has been rendered more crucial by the year, and is more present than any other social or human rights demand. 13 policemen (according to media sources in 2014) is an insufficient number to make a city full of crime secure. The local authorities, however, have been assuaging these fears with promises to build police departments and police patrols to control the situation and “clean” the city from people with criminal records.

The inhabitants are aware that a security approach alone cannot suffice, as social services must also be provided to establish the conditions for a dignified life without marginalization or “huqra” (contempt). To the youth, feeling the contempt of the state and others justifies their belonging to worlds of violence. The repeat that “the decision-makers and those in charge have cost us everything, robbed us, and disdained us.”

This class of young men in the city (like their counterparts in the margins and shantytowns of Morocco) will often point fingers at the state first; they would curse and swear at it in their daily talk and on social media, to the point where they would chant “Fi bledi zalmouni” (“they’ve wronged me in my own country”) in football fields as a form of protest to express collective rage. The marginalised neighbourhood guys, shoved into the “black ends” of a city, try to defy their being labelled as “brahech” (adolescents), which they consider a condescending term, by practising violence as a performative act.

This group seeks to fill in for the missing social roles in their communities. The lack in some roles is usually due to the profound shock that had hit the social structure, disrupting the former hierarchy and the values that used to envelope it. Such a disintegration stems from being rapidly uprooted from their places of origin, which would usually happen in a catastrophic manner, rather than as a natural development. The shift wasn’t accompanied by any stability either, whether in work or housing -regardless of how miserable those may be - but would be characterized by a precarious state of “barely getting by”. For instance, this group often assumes the part of the “big brother”, in the patriarchal and macho guardianship over their sisters or the neighbourhood’s girls, to protect their “honour” and make sure that they “respect the moralities of the neighbourhood”. At other times, the guys themselves feel the urge to practice their patriarchal and violent masculinity by harassing the neighbourhood girls or, in “the best of scenarios”, by supporting their friend from the hood in a fight or a violent argument.

It does not matter who gets elected

The electoral campaign began, with blue paper bills (200 dirhams) raining down on the electorate, along with gifts, promises, and soulless speeches offered with phoney smiles. When asked who they would vote for, the inhabitants would say: “It doesn’t matter if we elect a socialist party, Islamist party, or a ruling party from within the government itself. What matters is “who can serve us most?””

Koléa, like its counterparts of hybrid Moroccan cities, has consecutively lived under the reigns of various parties, leftist, rightist, Islamist, and governmental.

The end result was neither facilities nor any trace of a development that could impact people in a profound way. The city labelled as “a criminal stronghold” seeks to denounce the description in any way possible. The inhabitants no longer care for the politicians’ electoral slogans nor for their partisan alliances following the due date; they no longer care for their disputes as they vote for local projects that usually never see the light of day. They are even indifferent to news of the politicians’ involvement in political corruption files. “We feel ashamed. We don’t want our city to face this kind of fate…” – the inhabitants express their desire to improve the infrastructure and general conditions of the city they live in.

Practically, the city’s “elected” politicians promise to realise an integrative project that includes disinfection works (like establishing sanitation networks) valued at 56 million dirhams (around 5.6 million dollars). The important internal roads will “see the light of day” (as they say), like the first part of the regional road 1005, which would facilitate entrance into the city, as would a new line for the public buses that would pass through neighbourhoods next to the city. They also promise to consolidate public street lighting in a number of rural residential complexes and towns, to provide neighbourhoods with eco-friendly and economic light, as well as pave the alleyways. In terms of security, the people’s prime concern, the “elected” reassure them that a police station shall be established in the old municipal headquarters.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 10/10/2019

1- The government spokesperson, Mustafa al-Khalafi, stated that when the Zero Shantytowns project had been announced, the objective was to obtain 85 shantytown-free cities, which stipulates the construction of 270 thousand residential units. Instead, 277 thousand units were built; that is, the objective was more than met. However, as statistics were updated, there was now a need for 420 thousand residential units, which is an indicative figure – as it means that 59 out of the intended 85 shantytowns have been eliminated.

2- An area located in southern Morocco. It was named after the Sousse valley, which crosses the Taroduant and Agadir lands and their surrounding cities and towns.

3- All names that appear in this text are pseudonyms.

4- Since 2014, Morocco has adopted a plan to replace older taxis with bigger and more comfortable ones, through the support provided by the Ministry of Interior. Worn-out taxis, however, still exist (especially in big cities) as subsidies were lifted.

5- The figure only concerns the municipal market, the Tuesday market, the fruits and vegetables market, and the grains market, and not the liberty market, the liberty and metal scrap market, and the Qisariyat (a modern commercial complex).

6- Geographically, Koléa is located between the mostly rural Chtouka Aït Baha province and the Inzegane Aït Melloul region, where a hybrid urbanism prevails.

7- Koléa is home to different means of transportation, including urban transportation buses (a Spanish owned company), mini buses, and larger taxis, most of which drive people to Aït Melloul, Inzegane, and central Agadir. Demand for these, however, is on the rise; and so they are overcrowded on a daily basis, especially when it comes to urban buses, which have been subjected to numerous incidents of vandalism and robberies.

8- The public sector employees in the city make up 4.5 percent (the High Commission for Planning statistics in 2014).

9- An institution similar to an association or a cooperative with an aim to establish residential projects with low cost, to the benefits of its members – they pay determined sums of money over a stretched period of time as they share the purchased land and payment of its costs among themselves.

10- The current price used among real-estate companies is around 250 thousand dirhams (around 25 thousand dollars) of an area that ranges between 50 and 80 m2.

11- The percentage of people aged 20 to 34, and is at 9.4 percent of people aged 15 to 19 (According to the High Commission for Planning’s 2014 statistics).