B’Tselem, an Israeli organisation that monitors human rights violations, perpetrated by the Israeli occupation in the West Bank and Gaza, has recently issued a statement in which it announces adopting a new legal theoretical framework. The latter reclassifies the political situation “between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea”, by which the organisation gives up its previous discourse claiming “Israel is a democratic state though administers a system of occupation in the territories occupied in 1967.” It therefore realises now that “the territories under Israeli control are organised under a single principle: advancing and cementing the supremacy of one group – Jews – over another – Palestinians,” and proceeds to call it an “apartheid”.

The statement B’Tselem published fuelled a heated debate, ongoing for a few years now, about the definition of the Israeli regime. The debate has been taking place in the “human rights” sphere – that is, between Palestinian, international, and Israeli human rights organisations, United Nations bodies such as the UNHRC, the EU, along with European and American funds, and various academics researching fields related to the Palestinian question. Following its statement, the controversy centred around questions like: Why wait till now? Why has B’Tselem objected to adopting such a framework for so many years? Why refuse joining forces with human rights alliances to strengthen their position in that regard? Then, how come B’Tselem receives worldwide attention while Palestinian organisations, with that same position, remain ignored? Why not refer to Israel is a “settler-colonial” state? And how does B’Tselem’s analysis fundamentally differ from the Palestinian organisations’, though both call it “apartheid”?

While important, these discussions take place in a “human rights” realm, which seems to be a world of its own. It rarely peeps outside to see the foundations upon which the debate was originally based. It rarely observes the de-facto infrastructure that rules interorganisational relations, creates a hierarchy of legitimacy amongst them, and generates asymmetries of power and sway over formulating the international human-rights discourse. Naturally, such asymmetries are rarely professional or objective.

The Geneva Underground

The de facto structure that rules this domain is comprised of a number of different forces, starting with American and European funds (which play a decisive role in strengthening and weakening organisations), and Western ministries of foreign affairs, all the way to massive Israeli pressure, certainly, activated through several Zionist arms that engage in action and pressure tactics, and miss no opportunity to throw around false claims of “pro-terrorism” and “antisemitism”.

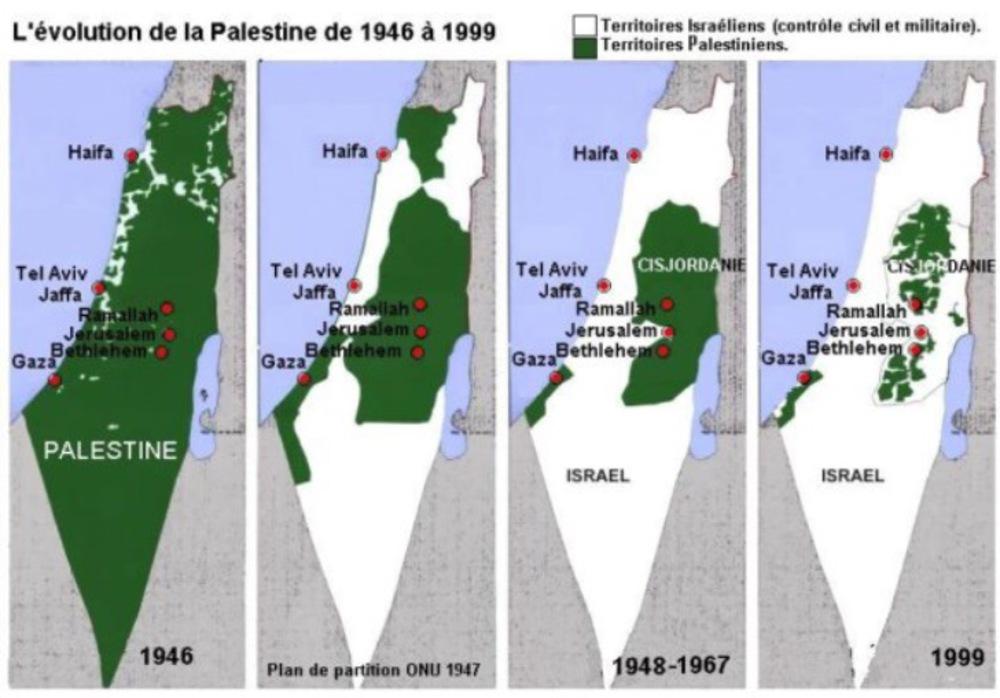

Most debates avoid discussing these entities and the effect they have on human rights organisations, their work, or relations. By choosing to remain silent about such structures, they turn into a “supernatural” force that sets the rules of the game to suit oppressive European and American interests and political visions, saturated with a sense of guardianship over the Arab region, and congruent, to a large extent, with Western government policies and their colonial baggage. The moment those financial and political forces disappear, the UN rights domain shows up in its pure and impartial attire, founded upon practices and platforms of a conventional discourse, linguistically sterilised, formulated in cautious diplomacy, and unwilling to tread but the punctilious paths of international conventions (irrespective of the glaring truths). Most importantly, though, intertwined questions eventually disintegrate; as such, to study the occupation of Gaza ceases to be directly linked with the West Bank, while connecting 1948 Palestinians with West Bank Palestinians is rendered a taboo. Needless to say, when discussed, these questions get historically decontextualised, all originally rooted in the Nakba and the establishment of Israel.

From a legal perspective, intertwined questions disintegrate; as such, to study the occupation of Gaza ceases to be directly linked with the West Bank, while connecting 1948 Palestinians with West Bank Palestinians is rendered a taboo.

Furthermore, the human rights theatre is designed to appear as a neutral space, clear of political identities. As such, it enjoys an important particularity, seldom discussed, despite its exceptionality: this is one of the rare domains where Palestinian organisations permit themselves to collaborate and coordinate with Israeli organisations on a regular basis, and without upsetting their patriotic standing among Palestinians. Such exception, which Palestinians would never afford other domains (cultural, social, or otherwise), lies beneath a multileveled premise that begs studying.

Such “neutral ground” prescribes that organisations maintain a high sense of rights-based professionalism, thus tricking us into thinking that they align themselves with nothing but the universal values of human rights. In fact, the delusion goes back to their definition as “independent” and “nongovernmental”. Those organisations are thus stripped of their national, ethnic, and class bearings, whereby all political incentives and goals, all political plans, disappear behind a rights-based discourse. It is precisely here that a meaningful difference lies between Palestinian and Israeli organisations, under which lie several substantial and hushed-up differences.

Them and us… spot the difference!

The “independence” of Palestinian organisations means their disconnection from any political liberation project. In fact, the rise of “nongovernmental organisations” in Palestine correlates (even if complexly or indirectly) with the collapse of the national liberation project. While Palestinian organisations are indeed disconnected from both Ramallah and Gaza governments, the story doesn’t end here. They are surveyed and persecuted for any connections they may make with Palestinian factions (besides Fatah) defined, in the West, as “terrorist”. As such, they could be punished for employing former political prisoners, subscribing to any political affiliations, or making any statements (or publishing a Facebook post), even if it came out of their most junior employee. The vast majority of organisations had to even distance themselves from the call for the boycott of Israel, and avoid referring to it in any shape or form. In other words, those human rights organisations do not pertain to a Palestinian political ground that has its own independent vision and plans; they neither belong to a political movement nor act as a legal arm as part of a national strategy. Human rights, in Palestinian organisations, a supreme value in and of itself, are played out as the latter wait for a political Godot to revive the Palestinian struggle and put it back on its emancipatory track, or for a turn of events that has the world willing to take Israel to court.

In the beginning, Zionist colonialism in Palestine was created from a racist principle – the “establishment of a Jewish State”. Its entity was founded on massacres, displacement, and the destruction of hundreds of villages and towns in 1948. A manifold legal configuration was thus established, which would go on to justify, in dozens of ways, the theft of Palestinian property, starting with the Absentees Property Law (1950).

This is far from what Israeli human rights organisations experience. While they are indeed nongovernmental –even anti-government–, Israel, its Zionist ideology, and socio-political streams remain much bigger than the government. Those organisations belong to a central, rather foundational, socio-political ground in the Zionist enterprise. They belong to an ethnic European Ashkenazi class that believes it pioneered the colonial enterprise and the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. Such Ashkenazi hegemony –or the “First Israel” as it is called– took over the absolute majority of pillaged resources, a list topped by Palestinian land and property. Resorting to Ben Gurion’s party, Mapai, under which rallied the majority of this class, and which dominated Israeli governments during the first thirty years following the Nakba, this social class took over administrative positions, and controlled the media, legal system, academia, and politics. Besides ethnically cleansing Palestinians and stealing their possessions, this class maltreated those Jewish immigrants hailing from Arab countries, turning them into an exploited workforce that suffered horrible social conditions.

This class still forms a political stream that prides itself on having established a Jewish state, and is convinced to be so close to losing that progressive, enlightened, democratic Israel that brandishes its European values. It even believes that the aftermath of the 1967 occupation, especially after the Likud party took over in 1977, is draining Israel in return for expanding settlement in the West Bank and Gaza, that its practices harm the enlightened democratic tenets that define Israel, and, most importantly, that perpetuating such occupation would end up with Arabs demographically outnumbering Jews between the river and the sea, thus losing Jewish majority, and, with it, the Jewish state enterprise.

Not history already

These socio-political associations continue today. Israeli human rights organisations have connections in the political arena, participate in parliamentary life, have their own representative media which they consider their own home-base, have strong presence in academic circles and, until a few years ago, enjoyed a certain extent of influence in the supreme court. They have the support of civil society institutions, like the New Israel Fund, founded by liberal Jews from the United States in 1979 (two years after the Likud replaced Mapai as the ruling party), in an attempt to pump donation money into organisations that represented their specific political spectrum. Until today, the fund still plays a key role in funding organisations and steering their political discourse. It is part of a much bigger picture, one in which Zionist American Jews –most of whom are affiliated with liberalism– support those organisations through influential pressure groups (like J Street) and with huge amounts of money.

To refute B’Tselem’s claim would require no more than a few lines, or perhaps a five-letter word: the Nakba… but a word nowhere to be found in the dictionaries of Israeli human rights organisations, which belong to a social base that created the Nakba and profited from it.

B’Tselem, along with many other Israeli human rights organisations, is part of this stream that sees upholding Palestinian human rights not only as a noble value per se, but also as a means to strengthen Israel’s position, to preserve its security and existence as a “democratic” Jewish state. In other words, to them, securing the rights of 1967 Palestinians, and granting civil rights to 1948 Palestinians, is the safest way to maintain settler colonialism and sustain it. Many human rights associations have shown similar views, too. Among those views, for example, is opposing a reinforced siege on Gaza because “the Israeli army and intelligence services had recommended improving Gazan economic conditions to avert escalations”. Another is to quote the Shabak (the Israel Security Agency) in its recommendation to oppose delegitimising a 1948 Palestinian party – to avoid its radicalisation. Another example is opposing extrajudicial executions, committed by the occupation army, because they contradicted “military ethics”. Numerous other versions exist, which stem from the same belief that the continued occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip would unravel in distorting Israel and destroying its enlightened democratic enterprise in the region.

The new B’Tselem position, then, should be understood within this ideological context. Its position does not change its understanding of Israel’s colonial racist essence; it rather intensifies an internal Israeli battle against Netanyahu’s government, after the domestic situation in Israel had reached a complete impasse, as they see it, all the while a regime-change or a transformed political decision-making seem doomed.

A bolded revision

In its statement in which it adopted an “apartheid” framework, B’Tselem bolded a highlighted heading in which it revisited its definition of Israel as a state of apartheid. Their revision escaped most news coverages and discussions, however. The organisation describes the regime it calls an apartheid as such: it “was not born in one day or of a single speech. It is a process that has gradually grown more institutionalised and explicit […] over time.”

Such a discussion conveniently forgets that Jewish organisations around the world, and even within the occupied territories, have been working for years without receiving that same international validation. Those include, for instance, Jewish Voices for Peace and Zochrot – both organisations fighting a public and courageous war against Zionism while documenting the ethnic cleansing that took place in 1948 and after.

To our limited knowledge, Zionist colonialism in Palestine was founded on a racist principle – the “establishment of a Jewish State”. Its entity was founded on massacres, displacement, and the destruction of hundreds of villages and towns in 1948. A manifold legal configuration was established, which would go on to justify, in dozens of ways, the theft of Palestinian land and possessions, starting with the Absentees Property Law (1950) and the remainder of land expropriation laws enacted in the first decade following the establishment of the state… All of which prove that the oppressive, racial, apartheid in Israel was not born “over time” and has not “gradually grown”. That is what the Martial Law proves too, which was applied with the Nakba in 1947 and effectively until the mid-1970s. It was first applied to 1948 Palestinians, where residents of the Galilee, the Triangle Area, and the Naqab were imprisoned within segregated areas which they could only exit with travel permits issued by the military; then, in 1967, a military rule over Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza was added, still in effect to this day. Add to that the brutal suppression of all political action, and the naturalisation policies that exclusively benefit Jews (the Jewish Law of “Return”, and the Citizenship Law) – both of which were indispensable to the foundation of Israel.

To refute B’Tselem’s claim would require no more than a few lines, then, or perhaps a five-letter word: the Nakba… a word nowhere to be seen in the dictionaries of Israeli human rights organisations. The latter belong to a social base that created the Nakba and profited from it. One need not search long to find boundless discussions about the most horrific crimes committed after 1967… However, to revisit anything preceding 1967 will always be taboo. The word Nakba shakes both social and economic foundations of that stream. The Nakba, and the questions it raises – such as the Palestinian refugee’s historical right of return, and the crimes of ethnic cleansing, along with the Palestinians’ right to self-determination, wherever they may be – are all elements that undermine the cornerstones of such a stream.

It’s about Zionism, not Jewish identity

One could often detect in B’Tselem’s discussions an identity politics busy with an ethnic race for rights-based or academic resources, as well as with claiming that the “white Jewishness” of organisations renders their voices louder and more effective. Such a discussion conveniently forgets that Jewish organisations around the world, and even within the occupied territories, have been working for years without receiving that same international validation. Those include, but are not limited to, Jewish Voices for Peace and Zochrot – both organisations fighting a public and courageous war against Zionism while documenting the ethnic cleansing that took place in 1948 and after.

B’Tselem refuses to engage with the Palestinian definition of Israel’s regime, or to consider Israel as a “settler colonialism that practises apartheid”, as defined by Palestinian organisations. This last definition connotes racial segregation not as a regime that lives off racist premises per se, but rather as a tool used to perpetuate colonial and settler presence.

The factors that grant B’Tselem its privileges in that imbalanced human rights field, is neither the Jewishness of its team nor the fact that it defines itself as Israeli – but rather that they are committed to colonial Zionist principles and belong to one of its streams. Such a stream, though now marginalised in Israel, still receives great support from US Zionists, where an extensive network of pro-Israel funds, institutions, and pressure groups, highly influential in the Democratic Party (which represents American Jews, as more than 75% support the Democrats) is concentrated. Additionally, more than a third of American Jews belong to Reform Judaism (the strongest third, class-wise) which clashes time and again with the religious-settler stream in Israel over Israel’s secular identity. As such, enormous funds are pumped from the United States into “secular” –and “leftist”– Israeli organisations to support them in their struggle for an “enlightened” Israeli identity. Perhaps the most obvious example could be seen in the millions of dollars sent by American Jews during Israel’s parliamentarian elections to overthrow Netanyahu’s government. The Israeli human rights organisations’ link to that stream explains why an organisation such as B’Tselem would refuse to engage with the Palestinian definition of Israel’s regime, or to consider Israel as “settler colonialism that practises apartheid”, as do Palestinian organisations. This last definition connotes racial segregation not as a regime that lives off racist premises per se, but rather as a tool used to perpetuate colonial and settler presence.

No matter how resigned and forgiving Palestinian organisations are willing to be, it is hard to imagine they would ever approve of such Zionist values. The very same colonial power relations, then, and political hegemony that exist between Israelis and Palestinians all throughout Palestine, are also replicated in the human rights domain. They hide, however, in the back of impeccable stages: on the one hand, we have Israeli organisations that function within coherent social and ideological structures, promoting their own interests through human rights tools, all the while intersecting with what is deemed acceptable politics in American and European terms, and, on the other, Palestinian organisations lacking political vision, scarred and torn apart by that very political fragmentation they fight. As such, an Israeli organisation’s word and its political and legal analysis would receive much more validation and popularity – but not because they uphold historical truths or accurate knowledgeability.

Lest B’Tselem become our escape from ourselves

In the “human rights” stock market, and in the shadow of a violent and continuous Israeli attack on that realm, where it throws accusations of antisemitism and pro-terrorism any way it likes, American and European funds prefer to invest in the least risky options: in those that do not claim to fight Zionism, talk about seeking Israel’s interests, too, and reject BDS in its totality (which, by the way, was viciously attacked by the New Israel Fund –which also funds B’Tselem, and other organisations– in its attempt to internationally delegitimise the boycott movement).

In the human rights domain, colonial power relations and hegemony between Israelis and Palestinians are replicated. They hide, however, in the back of impeccable stages: on the one hand, we have Israeli organisations that function within coherent social and ideological structures, promoting their own interests through human rights tools, all the while intersecting with what is deemed acceptable politics in American and European terms, and, on the other, Palestinian organisations lacking political vision and scarred and torn apart by that very political fragmentation they fight.

Israeli human rights organisations are not only aware of such privileges, but also wring every last drop out of them. They do so in two methods: first, they distinguish themselves from Palestinian organisations, which affords them financial lucrativeness and legitimised influence. Second, and most importantly, they impose, as they have many a time, legal frameworks and rights-based discourses on oppressed Palestinian communities, which are legal frameworks that have serious political repercussions that tear apart and fragment both Palestinian people and their rights. Israeli organisations move forward with such projects, in complete disregard of Palestinians and repulsive patronisation of these stifled human rights voices, which demand those frameworks be abandoned. Perhaps the most recent blatant example is when Israeli human rights actors tried to get international recognition for the Naqab Bedouins as an “indigenous people”, basing their demand on a folkloric narrative and the idea of an old-fashioned “lifestyle”.

And yet, Israeli human rights organisations are what they are. They never misrepresented themselves or lied about their values. There therefore is no room for shock here. Palestinian human rights activists’ anger, following the B’Tselem statement, is very understandable, however. They work in a field which they assumed to be fair, objective, and legal only to face injustices and discrimination there, too. Still, to be shocked, on the other hand, would presume some form of a shaken trust, an “anonymous” trust misplaced in Israeli organisations that have always been clear about their affiliations and views, and in a United Nations that never managed to seal one tangible win for Palestinians. This here is our own problem; we are the ones who lack a national liberation project and vision, whose rights-based dimension, incidentally, should constitute but one front, no more. Only within a context of a comprehensive emancipatory vision could a rights-based action enhance Palestinians’ human reality and uphold their rights. Only then might we realise the unbridgeable gap between us and Israeli organisations.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 30/01/2021