" This file was produced as part of the activities of the Independent Media Network on the Arab World. This regional cooperation brings together Maghreb Emergent, Assafir Al-Arabi, Mada Masr, Babelmed, Mashallah News, Nawaat, 7iber and Orient XXI."

Layla Yammine*

In one of the biggest private hospitals in the country, Hotel Dieu de France (HDF), Doctor Rami Bou Khalil spends much of his professional time negotiating with patients. There are so many who cannot afford the medications he prescribes to them that they come back to the clinic and ask for a change. Either in dosage, quantity, frequency or quality. Not because the patients feel fine, or because of side effects, but because the major side effect is, they say, “the cost of the medications.”

Dr. Rami Bou Khalil is a 44-year-old psychiatrist, practising his profession since 2012, and currently the head of the department of psychiatry at HDF as well as associate professor of psychiatry at the Université Saint-Joseph in Beirut. “I cannot say that the overall situation of people’s mental health is good, but people who are wealthy are getting high quality mental health treatments.”

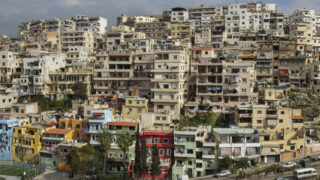

Since Dr. Bou Khalil started practising psychiatry, poverty in Lebanon has increased, especially since 2019. From 2012 to 2022, it went from 12 percent to 44 percent according to the World Bank, while the multidimensional poverty rate doubled from 42 % in 2019 to 82 % of the total population in 2021.

These drastic numbers result from an economic collapse described by the World Bank as being one of the “most severe crises episodes globally since the mid-nineteenth century.” The collapse has crippled the overall public healthcare system, which was already fragile and fractured due to the lack of national policies working towards a universal healthcare system.

The tremendous pressure since the start of the financial collapse has left millions of people unable to afford basic healthcare services.

Arab World: Mental Health, a Political Issue

26-06-2024

Already before this, Lebanon’s healthcare system catered to the privileged few. With very little reliance on support from the government, the country’s more marginalised communities remain exposed to any health issue, notably mental health issues.

The privatisation system, which is vastly common in Lebanon, has left many unable to reach mental health support when needed, with mental health services being so expensive that few can afford them.

These services range from simple access to counselling, long-term therapy with psychologists, therapy with psychiatrists and medication, all the way to mental health institutions. All of which are not covered by private health insurances, which, in parallel, 45 % of the population does not have any kind of insurance in the first place.

Not for everyone

In a small local coffee shop right next to the Lebanese International University (LIU), Samia and Nour (not their real names) sit with the rest of their friends. They joke, share notes from different classes, and sometimes are just there for each other. This coffee shop holds all their secrets.

Samia is a 21-year-old student at LIU, graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Radio and Television. The financial collapse has “ruined her life,” she says. She wanted to be a lawyer and study at the Lebanese University. But after the economic crisis, her father lost his job, became sterner with her, and possessive. He did not allow her to go to the Lebanese University because it was far from their house – a ten-minute car ride.

Instead, she had to find something else in a university that is closer to her parental house. During that phase, her siblings became the family’s providers which put extra pressure on her, because she always felt like she owed them.

Samia had to find a job; it was the only way she could start coming out of her family’s grip. The only job she could find was in retail. That was enough for her, because having a job meant one important thing: being able to pay for therapy.

“I knew that therapy sessions could cost as much as $20! Where could I get this amount from? It was impossible to find anyone who would accept less,” she says, frustrated. “Where would I go then? To NGOs?” she adds sarcastically. What Samia did not know is that some therapists charge up to $150 per session and that $20 was the minimum cost in very few clinics.

Instead, she sought help among her contacts. “I have a friend who studies psychology, he was my only resource, so I reached out and told him that I was looking for someone to help. I really needed it.”

Samia expressed her frustrations and financial restraints, so her friend, after a long search, was able to link her with an understanding professional who accepted a lesser charge than usual.

“And thank God I found him. In the few months I have worked with him, a lot has changed. I started understanding myself better, and my surroundings,” she explains, with a smile on her face.

Yet again, Samia had to stop the sessions, abruptly. She had left her job and could not afford the nominal price of the sessions.

Turning a blind eye?

In May 2014, the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) launched The National Mental Health Program, with the support of the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF and International Medical Corps (IMC). Even though the MoPH says that “the implementation of this strategy is successfully ongoing since its launching,” according to their website, there is yet a lot to do on the ground for it to effectively reach and impact the wider population. Additionally, the lack of proper funding plays a big role in its efficiency.

And so, in 2023, the MoPH launched yet another strategy, aimed at guiding the work that should be done in the next seven years, until 2030, the “National Health Strategy: Vision 2030.” This vision aims at setting out the framework for a sustainable and modernised recovery of the mental health sector and intended to address the challenges of leading a burned-out health system.

Meanwhile, the ministry also published on their website two main documents: the first one is a list of licensed psychologists in Lebanon, including their full names, the number of their licences and their specialisations, while excluding their contact information, locations and pricing of the sessions.

In parallel, the second document published is a list of primary health care centres that have a psychiatrist and specialised mental health medications, located all over the country. It was last updated in 2023. These centres aim to offer the essential health care for individuals and families in the community, at an affordable cost.

The problem with these small steps is that their effectiveness is very limited within intense budget cuts, where, by 2020, only 5 % of total governmental health expenditure was allocated to mental health services, and 1% of the Ministry of Public Health’s budget. Additionally, the low wages for public workers, and the limited access for the public – who still cannot afford a therapist, also restricts the efficiency of the ministry’s plan.

“People that want to access mental health services, but cannot afford to do so, can go to the primary health care centres,” Dr. Bou Khalil says. “But I don’t know how well oriented and informed patients are about the presence of these services.”

Additionally, Dr. Bou Khalil explains that the demand is much higher than what those centres are providing right now. “Millions of people for only 20 centres or so?” he wonders rhetorically. In fact, the overall number of primary health care centres that have a psychiatrist and specialised mental health medications is 58 centres, scattered across Lebanon, but they are not enough to cater to the high demand in public health services and especially mental health services.

The crisis also led to the exodus of doctors and medical professionals from Lebanon, which led to the migration of around 3,500 doctors, among them psychiatrists. As for many of those who are left here, many of them usually work in the private sector, considering that the devaluation of the Lebanese currency has significantly reduced the value of the public servants’ income. Dr. Bou Khalil thinks that not many psychiatrists would now accept working in the public sector because of the low wages and devalued currency. And they are not the only ones. According to a study done by the Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), 81 percent of the employed population are working in the private sector, while 16.1 percent are working in the public sector, by January 2022.

In parallel, the number of mental health specialists is scarce considering the overall number of the population. As of 2020, for every 100,000 persons in Lebanon, there are 1.21 psychiatrists, 3.14 nurses and 3.3 psychologists.

Lebanon: A Special Type of Rent

13-12-2020

Samia says that she would go if such services were available. “If the state provides these services, I will definitely go. Actually, I’d be the first one to go!”, she exclaims. “Right now, our economic situation is very bad. We need these services.”

But meanwhile Samia and her friends find solace among each other. “We all have a story and an issue, some have financial issues, some have family issues, some have education issues… we just support each other in the best way we know and can.”

Less stigma?

Nour, who is 35 years old and studies Radio and Television, the same major as Samia, is one of her friends. A few years back, he was working at a local TV station and had to shoot a report with a psychologist. After hearing her speak about mental health, it made him rethink his preconceived notions about the topic.

He used to think that those who sought mental health support were “mentally ill,” he says. But he decided to try a few sessions without telling anyone about it and felt its effect in his life. “Things, like the way I perceive myself and others, changed for me. I learned how to deal with my society and bullies around me,” he explains. “I felt as if a rock was removed off of my chest.”

Nour remembers when he was younger, playing with his neighbours, and how they used to bully each other and call each other “mentally ill,” or “insane.” Some kids even used to threaten each other with psychiatrists. “I swear I will take you to a psychiatrist!” they would say. “But this is ignorance,” Nour adds.

Samia thinks that the economic crisis really pushed people to rethink the importance of mental health. “The subject was taboo,” she says.

“People used to think that whoever goes to a psychiatrist, or a therapist is mentally ill, or insane, and the person would be stigmatised immediately. But after the crisis, I think people are looking at the situation from a different perspective.”

But now, Nour also had to stop therapy. “I cannot even pay $10 for the session. I have financial priorities now, but I wish I could go back.”

He is now forced to make choices and prioritise basic survival needs over his own mental health situation.

Dr. Bou Khalil sees things like this with many patients. “They cannot take care of themselves and their mental health because they need to pay the bills, so they self-medicate, and some start using cannabis and alcohol instead,” he explains with frustration.

Exhaustion

Since the financial collapse, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the explosion in Beirut’s port, the mental state of people has become very fragile. Dr. Bou Khalil says that the period immediately following these traumatic events was extremely hard.

“We were witnessing people putting an end to their lives because they couldn’t feed their children, they couldn’t find jobs, they had lost their money in the banks. Violence and self-harm became the usual headlines in the news,” Bou Khalil says.

But in the last year or so, people have tried hard to push back against all the collective and individual traumas, where the percentage of suicide cases declined almost 19 % in 2022 from 2019. But with the deep lack of services, many are still incapable of seeking help.

According to Dr. Bou Khalil, the situation can be improved by increasing awareness, reducing stigma and improving and covering for services.

“We are all destroyed,” Samia says with tears in her eyes. “All of us, all the Lebanese people, are. Our situation is dire.”

“People are exhausted,” says Dr. Bou Khalil. Many live in uncertainty and leave their mental health unchecked and untreated.

Yet other traumas are lingering: war. Since October 7, the population has been exposed to daily images of violence and atrocities stemming from Gaza, and since October 8, Israeli aggression in the south of Lebanon has been increasing. More than 450 people have been killed as a result and hundreds injured, villages partially destroyed. Most fear that this war will expand, and its wrath will fall upon the entire country, increasing the daily anguish, fear, and anxieties of what’s next.

Samia was laying back on the light green coffee shop’s couch, comfortable, smiling, and talking about her friends and her support system. But the moment she thought about the future, her body got tense, she sat straight up, washed the smile off her face, joined her fingers together as if she was praying, and said, almost whispering, “nobody knows what will happen, we have to go through it day by day for now.”

“We are not protected. […] We are vulnerable to high levels of psychological breakdowns and mental health problems,” says Dr. Bou Khalil.

- Researcher from Lebanon

- This article is written by Leila Yammine for Mashallah News as a part of a file produced by the Independent Media Network on the Arab World. This regional cooperation brings together Maghreb Emergent, Assafir Al-Arabi, Mada Masr, Babelmed, Mashallah News, Nawaat, 7iber and Orient XXI.