This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

For some women, the journey starts as soon as their schooling is interrupted, and due to their families’ poverty, their poor or non-existent education, and the lack of alternatives, the workshop becomes their fate. For others, it begins after a failed marriage or divorce, which means the women become dependent on their families again, the very families that married them off in the first place to lighten their financial burdens. This homecoming complicates things for everyone, and women find themselves in need to justify their presence in the home by bringing in some money. Since very few of them are willing to work as domestic workers, the workshop presents itself as their only option.

Then there are those whose journey starts with discovering that their husbands are unemployed or barely working, and so the workshop becomes their way of providing for the entire family. These families tend to include a considerable number of children, who, almost without the mothers’ noticing, seem to multiply like rabbits. Unplanned mothers, unplanned wives, and unplanned workers; everything in their lives seems to arrive as if by accident.

Tens of thousands of women work in one of Morocco's largest and most precarious manufacturing sectors under bad conditions, often working unpaid overtime, without any rights or Social Security, and in exchange for meagre wages. They are fully exploited, not to mention sexually harassed, due to their financial need, lack of qualifications, and the absence of other opportunities in their lives.

These are the women powering the textile industry in Morocco, which was, for a long time, one of the main industrial sectors in the country before technological industries entered the scene. Dependence on this sector declined as production from Turkey and China – two giants on the clothing and textile industry - flooded the global markets.

The importance of this industry for the employment of the people in Tangier is understood when considering that the city includes four Industrial Zones. The most recent of these, Tangier’s Automotive City, is run by manufacturers of cars and airplane parts. The three other zones are Gzenaya, Mghogha, and Al-Majd, with the latter mostly operating textile factories. Among the three, the Free Industrial Zone Gzenaya is the largest, attracting global conglomerates from different manufacturing sectors including: automotive, aviation, textile, food manufacturing, electronics, and services.

Early suffering

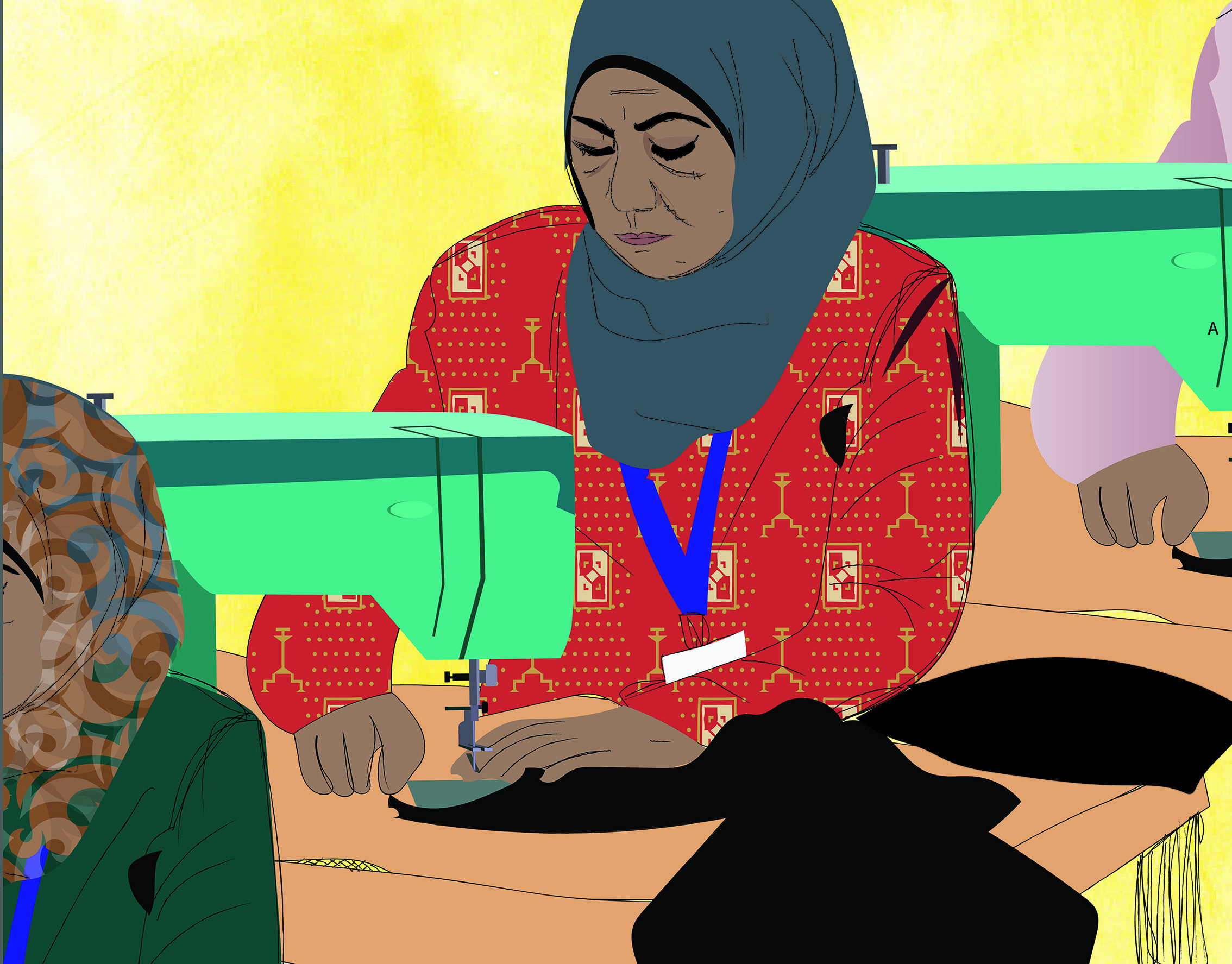

The women of the Industrial Zone in Tangier - the second most economically important city that includes the largest number of textile manufacturers - start their day at five in the morning. They return home after nine to twelve hours of physically demanding, back-breaking labour, with only a 30-minute break for having lunch and using the toilet. Each takes her place behind the sewing machine, like a robot operating another robot.

The plight of a textile worker begins before sunrise, with the issue of transportation. Workers wake up early to reach the designated meeting point, which is usually far from where they live, to catch the shuttle bus that takes them to work. The bus driver refuses to make any stops other than the designated ones. Since they leave before dawn, this daily trek leaves them vulnerable to theft, attacks, and sexual harassment. On their journey, they are easy prey for predators and thieves.

Tens of thousands of women work in one of Morocco's largest and most precarious manufacturing sectors under bad conditions, often working unpaid overtime, without any rights or Social Security, and in exchange for meagre wages. They are exploited – not to mention sexually harassed - due to their financial need, lack of qualifications, and the absence of other opportunities in their lives.

If they are late for work for any reason, a day’s wage is deducted from their salary. If they complain about the trip, the shuttle driver’s response is that he’s obligated to do one trip there and back, in one hour’s time, without any delays, covering a distance of more than 20 kilometers, and making many stops to transport the workers. If he’s ever late, for whatever reason, the company manager would issue a complaint against him to the transportation company, and he would lose his job.

It’s a cycle that grinds all workers, both men and women, but it is especially harmful to women, who are subject to harassment and blackmail in the workshop, the shuttle bus, and even on the streets. Their workday starts right away without a chance to catch a breath. These women are forbidden from using their phones, going to the bathroom, or talking to their fellow workers. They are only allowed to stop working at twelve thirty, when the supervisors grant them those precious thirty minutes. They are constantly under the surveillance of the company’s security men.

Women in Fieldwork: Ytto Convoys in Morocco

30-07-2022

An investigative report about textile factories in Tangier, conducted by a Spanish television channel in early 2019, revealed many violations related to poor work conditions in the industry, from tight work spaces that don’t meet health standards to workers being exploited for pay that does not exceed 500 dirhams (about $50 dollars) a week. The report also showed that the female workers in some of the textile factories in Tangier work for long hours to produce cheap clothes, which are later sold in Spanish stores for expensive prices. Spanish investors seem to have found a golden opportunity in the Moroccan textile industry, which awards them with huge profits in return for cheap labour and low production costs. Some items of clothes get sold for 10 times their real cost. No official numbers exist outlining the actual profits of the companies that handle these Spanish brands, but some sources report that nearly 95% of textile and clothing factories in the Industrial Zones in Tangier work for foreign clientele, mostly Spanish, followed by the French.

More hours and fewer rights

If the workshop manager wants to double production due to a rush order or increased demand, work hours could extend until nine at night. In return, the workers are paid for a regular work day, set by labour laws at 7-hours per day, at the minimum wage cost of 11.77 dirhams per hour. The workers are never paid more than that. In fact, insurance is deducted from their salaries, but seldom does the employer pay the sums deducted to Social Security, in the event that the workers are declared to Social Security in the first place. The employer evades paying Social Security dues which pile up as the months and years go by, due to the lack of oversight and the complicity of corrupt government workers. The victim is always the women workers. If accumulating dues to Social Security become enormous, contractors may declare bankruptcy to avoid paying them.

According to a report from the National Social Security Fund that pertains to their female benefactors, the number of workers declared at the Fund jumped from 184,623 in the year 1990 to one million and 109,737 thousand in the year 2018.

Other than the factories in the city’s Industrial Zones, there are hundreds of “garages” in residential neighbourhoods that operate as textile factories. That is why official numbers don’t reflect actual numbers of workshops in Tangier. Usually, there are more than 350 workers in an area that is barely 500 square meters. Most of the women in this sector have never signed a contract. For those who have contracts, their wages aren’t declared in total to the National Social Security Fund. Even those whose wages are declared are usually surprised that their managers never pay their insurance premiums. These discoveries could come either early on, or after years of work. There are many cases like these, some reach the courts, while others are advocated for by organizations that specialize in women workers’ rights.

During the period 2000-2018, the percentage of female workers declared to the National Social Security Fund (in all sectors including textile) was 31% of the total number of female workers. According to a report from the National Social Security Fund that pertains to their female beneficiaries, the number of workers declared at the Fund jumped from 184,623 in 1990 to 1,109,737 in 2018 (that is, an annual increase of 6.6%).

As for retirement, the same report mentions a noticeable leap in the number of days accumulated by retired women during the last 29 years, from 4,858 to 6,172 days; a 27% increase as opposed to the 3% increase for their male counterparts. This may be due to the fact that the number of women who have entered the workforce in Morocco has substantially increased in the last quarter of the century, while the number of men has remained the same, with the consideration that the phenomenon of women in the workforce is new to Moroccan society, only adopted in the last few decades.

In Morocco: Women Draw Light out of Darkness

06-07-2022

When it comes to family benefits, the report highlighted that only 13% of beneficiaries are women. This is because when a husband and wife are both covered, only the husband has the right to receive family benefits. There are some cases where the right to receive these benefits can be transferred to the women, such as in the case of divorce, when a woman has custody of the children, or if the husband is unemployed. The report also mentioned that 39% of women declared to the Fund in 2018 have benefited from obligatory health insurance, while the rest couldn’t, either because their premiums haven’t been paid, or because of a clerical error in their registration or processing.

Harsh working conditions and unfair layoffs

Talking about these sufferings is a tear-jerker for those women who have worked for the textile industry while holding back their tears for years. In one worker’s case, her 30-year silence ended with her losing her eyesight during her time in a textile factory in the Tangier City Port. She then found herself unemployed, along with 270 of her coworkers, when the owner simply shut down the workshop without giving them notice in 2018.

Another worker, who started working in a textile factory in her early twenties, found herself unable to thread a needle after two decades of work because of eyesight issues. The manager demoted her to a janitor once she became “obsolete” for the workshop - treated like an old sewing machine. As if it wasn’t enough that she lost her eyesight in return for a wage that, in the best of cases, didn’t exceed 2,300 dirhams a month, the workshop had only declared her to Social Security in 1993, after she had been working “illegally” for 10 years. Even after she got her Social Insurance card, she couldn’t take advantage of it because her employers never made the necessary payments.

When it comes to family benefits, the report highlighted that only 13% of beneficiaries are women. This is because when a husband and wife are both covered, only the husband has the right to receive family benefits.

Although the National Social Security Fund’s Office of Control and Inspection attempts to implement legislation that ensures social protection and addresses compulsory enrollment, registration, and declaration of wages; employers always find ways to circumvent the Fund’s measures.

Nadia, who has worked in a textile factory in a residential neighbourhood for a year, was not declared to Social Security even though she had directly demanded it. She was always met with the same indifferent response from the employers: “If you don’t like it here, there are others who would kill for the opportunity.” And so the workers suffer in silence, facing daily oppression. They can’t complain to inspectors either for a number of reasons, including the fact that those in charge always take the employers’ side, while workers are the weakest link in the chain. Most women do not join labour unions that could protect them out of fear of intimidation or getting fired. In addition, most of these women are under or uneducated and are unfamiliar with the mechanisms of labour unions. Most labour contractors warn workers against joining a union, threatening them with losing their jobs. The fact that these women are desperate, with no financial means or other alternatives, makes them even more susceptible to exploitative work environments, which in turn makes them the perfect employees for these companies.

One worker revealed that she only decided to join the union after she had lost her job. While she was employed, her boss used to say, “I will fire anyone who wants to join a union, and there won’t be any consequences for me”. After firing her, he blatantly told her and her coworkers: “Go to the authorities and submit a complaint. Let’s see what happens. I owe you nothing”.

After being fired, holding on to the termination letter is crucial to ensure a worker's rights. But most of these women have had very little or no schooling at all, so they’re unaware of their rights. One worker tells a story in which she reached out to the labour inspector’s office, so the inspector summoned the factory owner and confronted him. Because the worker kept her termination letter and her Social Insurance documents, whose dues weren’t paid by the employer, the factory had to resolve the conflict amicably. Under pressure from the inspector, the worker returned to work after two months. However, her case is the exception out of many who have lost their rights and jobs.

According to a report published on October 23, 2018 by the organization ATTAC Morocco (A leftist group advocating for the rights of workers and other disenfranchised groups, which is based in Paris and has branches in different countries including Morocco), the managing owner of one company steals employees’ wages (a worker may work for nine hours which are logged in by the manager as eight, for instance), doesn’t pay for overtime as per Article 201 of the labour law, and denies workers time off for public holidays. Managers and owners also often deny their workers formal written contracts, which always leaves workers in a precarious position, constantly at risk of losing their jobs.

The report adds that a larger number of workers are denied Social Security and health insurance. In addition, health and safety standards are not met in their workplaces: the women suffer from back pain because of inappropriate chairs, the workspaces are packed, which poses an ever-present fire hazard, while sewing machines sit back to back, and workshops also lack proper First Aid kits. As for the cafeteria, if it even exists, it doesn’t abide by health and safety standards, it is not large enough to accommodate the workers, and it serves very expensive food.

Layoffs through fraud

The workers are often surprised that production is halted in the companies they work for and that they are laid off without prior notice. This entails compensations as guaranteed by the labour laws for “technical unemployment”, as well as other rights. In one company, female workers found themselves without pay for three months.

Male and female workers hence band together, staging protests in front of the company that has dispensed with their services, and appealing to courts with a collective lawsuit. As a result, they encounter several attempts to push them into individual litigation through the justice system. The protestors then realize the absence of their “allies” - including the Directorate of Labour, local authorities and the Regional Committee for Inspection and Reconciliation (which never convene) - who were supposed to intervene and pressure the owners of the factories to fulfil their financial obligations.

Textile workers also don’t get compensated for paid vacation days (national and religious holidays), nor are they compensated for annual holidays. One unionized worker, who was recently suspended from a textile factory, has confirmed that most companies located in the city’s Second Industrial Zone do not provide the workers with necessary facilities, including a medical facility.

According to a report by a labour committee in the industrial zone, female workers are also subjected to verbal insults and abuse, as well as sexual harassment and exploitation from their employers or other superiors. Company owners in the industrial zones coordinate efforts to block the emergence or success of any unionized action. They do this by alleviating the pressure on the company experiencing labour strikes, whereby production demands are met by other companies instead.

Meanwhile, solidarity and labour coordination remain weak. With a complete absence of any central supervision of disparate trade unions, the workers have no protection from transgressions by the employers (often called the Patrona, adapted from the French “Patronat”) who are represented by the General Confederation of Enterprises in Morocco. Self-organized groups of workers try to coordinate union action, but the presence of women in these bodies remains minimal.

Few options and poor supervision

For most female workers, there aren’t any alternatives to working in the textile industry. Work in that industry is better than other options that are available for women without education or vocational training. At least textile factory workers, make more than those working as domestic workers, in stores, in kindergartens, or doing jobs in factories that are even less profitable or formalized.

Samira used to work in a kindergarten and her salary never exceeded 1,000 dirhams a month for an average of 12-hour workdays. Even though her work in the kindergarten is less physically demanding, since it involves taking care of up to four infants, it takes up her entire day. This mother of two gets home just in time to prepare the following day’s lunch, then, drained of energy, she falls asleep without being able to do anything else. Meanwhile, in the workshop, the starting salary is 2,500 dirhams for eight hours of work on normal days, when there is no extra demand that requires overtime, which could go up to 12 hours.

Morocco: A Kingdom of Rent

18-04-2022

For Samira, the latter is the better option. She has chosen to remain in this job for over 10 years. Now, she’s in charge of a sewing machine and her salary exceeds 4,000 thousand dirhams. Considering that her school education does not exceed the elementary level and that her husband's work pays little, her job at the factory represents her best possible option in the absence of other opportunities.

The value of the sector's exports amounts to 39 billion dirhams (about four billion dollars), while the local textile and clothing market suffers from unregulated labor, smuggling, and the general lack of an infrastructure. The workers in the sector have also been complaining about the competition since the market was opened under the free trade agreement.

Rarely do women who work in textile get promoted, because the managers are usually men. After gaining experience in the field, the only opportunity for promotion available to them is to supervise a group of workers within the factory. So most of them remain in the same place, behind the same machine, for years.

All workers emphasize the lack of supervision, even though one of the tasks of the labour inspectorate is to ensure that working conditions are up to par with Moroccan labour law. However, with a small number of inspectors, and the possibility of collusion between them and the employers, they become ineffective. For the women working in the textile industry, working as an inspector does not lead to any real improvement in their working conditions.

Declining markets and fewer jobs

Women workers are suffering from the lack of opportunities in the textile industry because of the sector’s decline in Morocco due to imported products competing with local products. As the form of production, the majority of employees in the textile sector in Morocco work through subcontracts (whereby one company assigns another to produce a commodity on its behalf). The Spanish market constitutes the largest destination for products, accounting for more than 40% of exports.

The Moroccan textile sector faces great challenges, despite being the largest source of employment in Morocco's industrial sector, with 600,000 jobs, of which 200,000 are in the formal sector and about 400,000 are in the informal or parallel sector, according to data from the Moroccan Association of the Textile and Clothing Industry (AMITH).

The value of the sector's exports amounts to 39 billion dirhams (about four billion dollars), while the local textile and clothing market suffers from unregulated labor, smuggling, and the general lack of an infrastructure. The workers in the sector have been complaining about the competition since the market opened under the free trade agreement, opening up the Moroccan market to 56 countries. This results in flooding the market with foreign goods, particularly from Turkey and China, according to professionals in the sector.

According to the State’s Secretariat of Foreign Trade, the textile and clothing sector in Morocco is a strategic and vital sector, constituting the equivalent of 35% of national industrial jobs and 4% of total employment in Morocco. The State Secretariat in charge of foreign trade in the Ministry of Industry, Trade, Investment and the Digital Economy revealed that, at the beginning of 2019, the continuous rise in Turkish exports to Morocco, which reached 200% between 2013 and 2017, has led to the loss of about 46,000 jobs in the period between 2013 and 2016. According to the same statistics, the market share of local production has decreased from 79.70% in 2013 to 69.30% in 2016.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Serene Husni

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 01/04/2019