This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

At a distance of 50 kilometers to the North West of the Sixth of October City near Cairo, one can see in the horizon, amidst the barren desert, big reclaimed farms of 170 thousand feddans (1). Meanwhile, diggers and reclaiming workers are working in full swing to bring the project’s area to one million feddans that have been allocated to 70 major investors, private companies, and some government agencies. The first thing that one notices is the huge cost of this enormous project, in which the government digs the water wells and provides the irrigation systems, in addition to other services, including a 500-megawatt power plant. Meanwhile, the investors acquire the land at a very low price and enjoy payment facilities.

This project, known as “Egypt’s Future”, constitutes the cornerstone of the strategy initiated by President Abdel Fattah El-Sissi. It reclaims 1.5 million feddans in the first stage of the project that is set to eventually cover 4 million feddans. For the execution, El-Sissi relied on the ministry of agriculture and the army through the founding of a company called The National Project to Develop Egypt’s Rural Areas that includes leading figures from both sides.

The 1.5-million-feddans phase has received a lot of publicity and repeated the official discourse that has depicted it as a national project that will change Egypt’s future and achieve its food security. Yet, the current preferences of El-Sissi’s administration reveal a different target. The Egyptian authorities seek to create a new and more profitable agricultural pole, based on the concentrating of vast properties in the hands of the major domestic and foreign companies, as well as the army in particular, which has been given substantial agricultural allocations -away from the original agricultural blocs on the banks of the Nile. El-Sissi seems impressed and inspired by this policy and by the army‘s profitable farms that spread everywhere. Those farms were established at different eras and are rooted in former president Sadat’s decision to allow the army to engage in civilian production.

It is not particularly odd to notice that the government has allocated a big part of the agricultural budget to execute this project, which is sponsored by El-Sissi and constitutes a fundamental part of his presidential program, despite the fact that venturing to cultivate the desert has been a risky experiment since the middle of the last century. This means that it runs the risk of turning into another ghost project, as has happened in earlier projects (2).

As we move away from this positive facet of conquering and cultivating the desert, the situation at the two banks of the Nile seems bleak. These governmental trends have further aggravated the fragile and declining conditions of the farmers and villages that have been deteriorating since the open door policies which were adopted by President Sadat in the 1970s, and the subsequent laws that served feudalists and big companies at the expense of the small farmers.

Policies liberalizing the agricultural sector

The advent of El-Sissi in 2013 was welcomed among the ranks of small farmers in Egypt. They saw in him the image of a new military general who could follow the path of former president Gamal Abdel Nasser in making huge agricultural reforms that served a large part of them. However, they were soon shocked by the radical, liberal policies that had an impact on the agricultural sector. In 2014, the government decided to remove all subsidies to agricultural production inputs. It also did not interfere to help the farmers following the floating of the currency in November 2016. This was accompanied by reducing the expenditure on the irrigation sector. Besides, it coincided with the rise of the complaints of many farmers from the deterioration of the canals and the low level of water that could not even reach some of the lands, especially in the Delta and some of the other governorates that are far from the flow of the Nile, like Fayoum in the west of Egypt.

These liberal policies, accumulated since the rule of Sadat, led to a four-fold rise in the prices of fertilizers in the end of 2014 (from 1500 Egyptian pounds per ton to 5600). The prices of seeds also increased at a rate of 100 percent, not to mention the rise in the prices of diesel and pesticides. The Ministry of Awqaf (endowments), which according to official figures owns 390 thousand agricultural feddans, increased the small farmers’ rent from 1800 pounds in 2013 to 5700 in 2019. All this led to the erosion of the marginal profit of the farmers in a state that already suffers from a large gap in income, making agriculture a non-favorable sector for the new generations.

There are two emergent phenomena which pose a threat in the long run to agriculture at the banks of the Nile. The first is the migration of the youth from the villages to the major cities, Cairo in particular, as well as abroad, seeking big and quick profits so that they would compensate for the insufficient incomes they made on agriculture. They run away from the tough living conditions and the aggravating shortage in basic services in their villages, looking for jobs to help out their families. The second phenomenon is the resorting of many farmers – especially after the January 2011 revolution - to selling their lands for construction in order to compensate for the insufficient agricultural incomes. According to official estimates, the areas Egypt lost due to construction after the revolution range between 84.66 thousand feddans and 120 thousand. As a result, the Egyptian government has launched extensive campaigns to remove the infringements on the agricultural lands and imposed heavy fines, in an attempt to hinder construction projects on agricultural lands.

Policies transforming farmers to “wage workers”

According to the latest statistics of the Egyptian government’s Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics for the fiscal year 2016-2017, the total area of the cultivated lands in Egypt is about 9.13 million feddans (some researchers believe that these figures are exaggerated), of which 6.9 million are in the old countryside, the valley, and the Delta, while agriculture contributes about 14.7 percent of the gross national product.

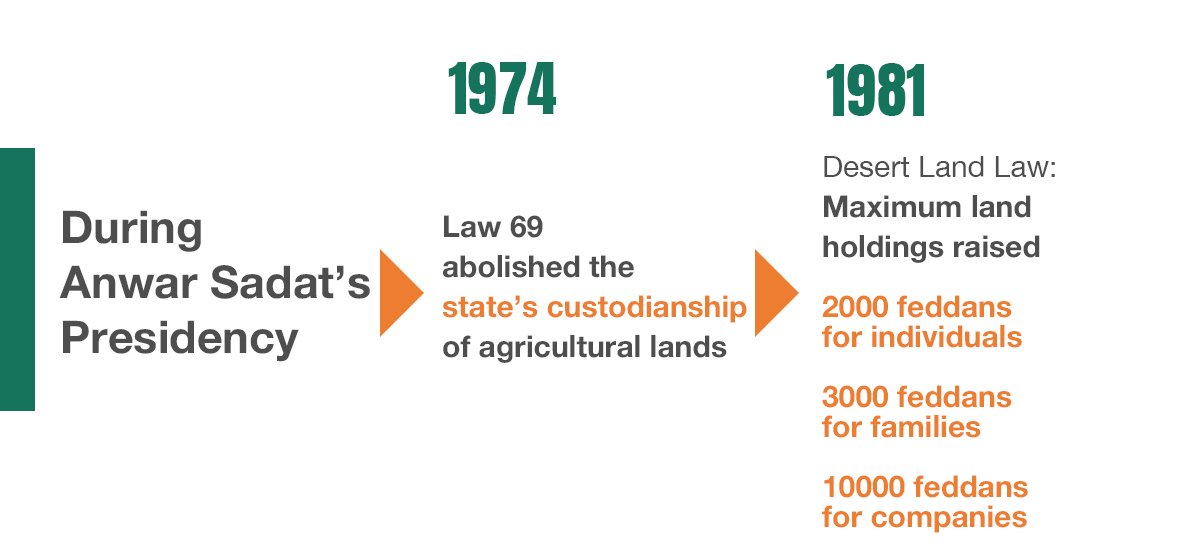

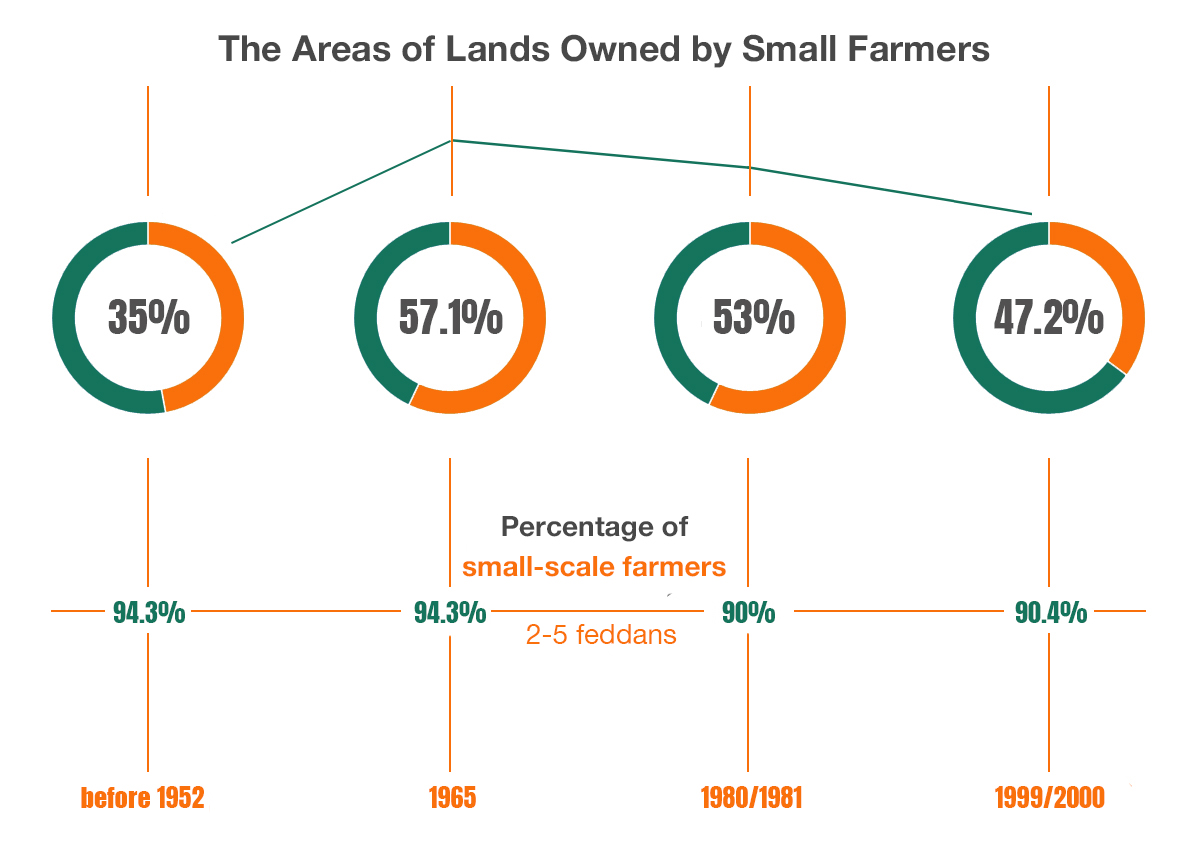

The Free Officers Revolution of 1952 shed light on the harsh living conditions of the small farmers in Egypt. Those farmers were affected by the colonial policies that turned Egypt into a production unit that serves London’s treasury. The pre-revolution era witnessed a huge concentration of agricultural lands in the hands of few feudalists and descendants of foreign families, who enjoyed political influence through the king and the colonial authorities. Although, at that time, while the small farmers represented 94.3 percent of the total holders, they owned only 35.4 percent of all agricultural lands.

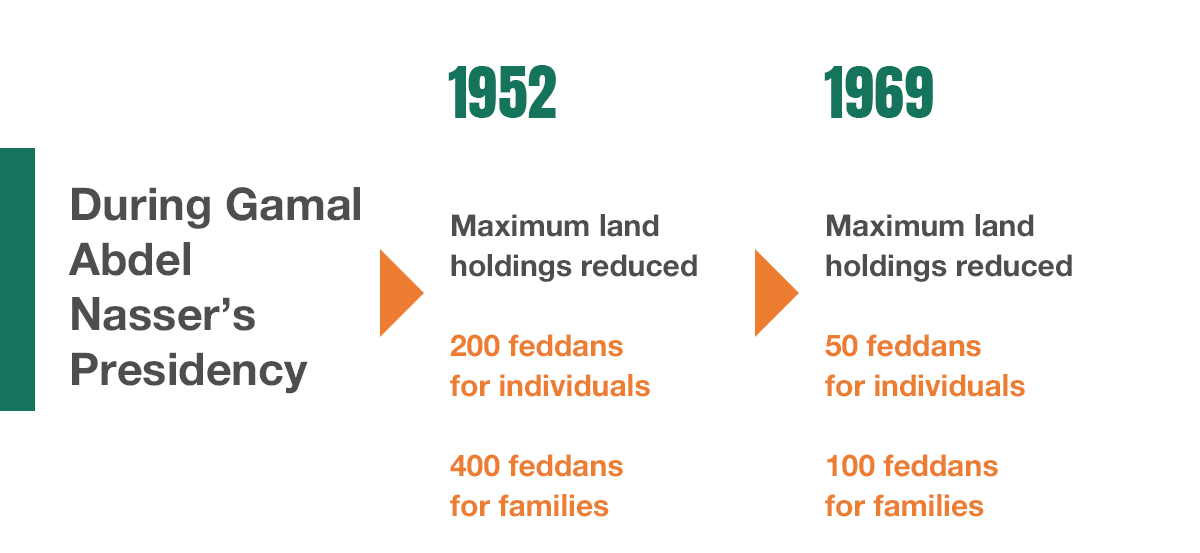

After the overthrowing of the monarchy and the declaration of the republic in the early 1950s, the state’s policy towards land ownership passed through three stages. It began by Abdel Nasser‘s declaration of a series of land reform laws, starting with setting a cap on the area of permissible land ownership, in an attempt to weaken the influence of the overthrown regime’s men and win the support of the poor class. In 1952, Abdel Nasser limited maximum land holdings to 200 feddans for individuals and 400 for families before it was decreased yet again in 1969 to 50 feddans for individuals and 100 for families. The state distributed some excess lands, in addition to those appropriated from the Muhammad Ali dynasty, on the small farmers, whether through lease or ownership in return for long-term installments before they were canceled.

Because of these policies, the share of the poor and small farmers in agricultural land holdings increased form 35.4 percent to 57.1 percent in 1965. According to a study by researcher Hassanein Kishk (3), these reforms were accompanied with offering production inputs subsidized by the government through the agricultural cooperatives that were founded in all villages. Through these cooperatives, the government was able to control all crops, as well as purchases and sales. They also provided loans to the farmers in return for the crops.

However, these profits gained by the farmers as a result of Adbul Nasser’s socialist policies soon began to shrink when his successor assumed power. A year after ending the war in 1973, Sadat endorsed law 69 of 1974, by which he abolished the state’s custodianship of agricultural lands and lifted the state’s custodianship on the lands seized by the Public Authority for Agrarian Reform from the major holders during the era of Abdel Nasser. He then gave these lands to their inheritors after evacuating the farmers who had acquired them by lease from the government itself. This meant hundreds of small farmers lost the lands they used to cultivate. Afterwards, the law of the desert lands of 1981 raised the limit of maximum holdings for individuals to 2 thousand feddans, 3 thousand for families, and 10 thousand for companies.

Together, these two laws dealt a blow to the maximum limit of land holdings as set by Abdel Nasser and paved the way for a new era (with the open door policies of the 1970s) that concentrated the ownership of the lands in the hands of businessmen and rising companies. The trend was further consolidated during the era of Sadat’s successor, Husni Mubarak. These policies drastically changed the percentage of small farmers’ land holdings, reducing it to 53 percent of the overall holders of cultivated lands according to the Central Agency for Mobilization and Statistics report of 1981, as compared to 57.1 percent in 1965. Under Mubarak, the policies of agricultural and economic liberalization accelerated, coupled with encouraging private capital to invest in agriculture, especially with the mounting pressures of the IMF following the two loans Egypt obtained in the beginning of the nineties - through policies that called for reducing subsidies in the inputs of agricultural production including seeds and fertilizers as well as continuing to weaken the role of cooperatives to the benefit of the Agricultural Development Bank that played a role in giving loans to the farmers.

A year after ending the war in 1973, Sadat endorsed law 69 of 1974 by which he abolished the state’s custodianship of agricultural lands and lifted the state custodianship on the lands seized by the Public Authority for Agrarian Reform from the big holders during the era of Abdel Nasser and gave them to their inheritors after evicting the farmers who had acquired them by lease from the government itself.

In 1992, Mubarak issued law 96 to “correct rental relations between landlords and tenants”, which was put into practice in 1997. This law annihilated whatever was left of the gains attained by the farmers from the reforms of Abdel Nasser, as the law decontrolled the rent prices of agricultural lands and allowed major landlords to retrieve the lands that were leased to farmers. This law, according to researcher Saqr al-Nour (4), has led to the expulsion of about 904 thousand tenants (31.1 percent of the owners) and the loss of land possessions of 431 thousand families who either turned into wage workers for the major holders or moved into other sectors. The law also led to quadrupling the rent of agricultural lands from 200 Egyptian pounds per feddan to 800 pounds during the first five years that followed its taking effect, before it jumped to 17 times as much in the year 2009.

This law caused demonstrations and violent clashes between the small farmers and the police and landlords in more than 100 villages, most of them in the Delta and the middle of Egypt. This resulted, according to the Land Center for Human Rights, in the death of 32 farmers and the injury of 751, in addition to cases of torture, intimidation and illegal detention by the police.

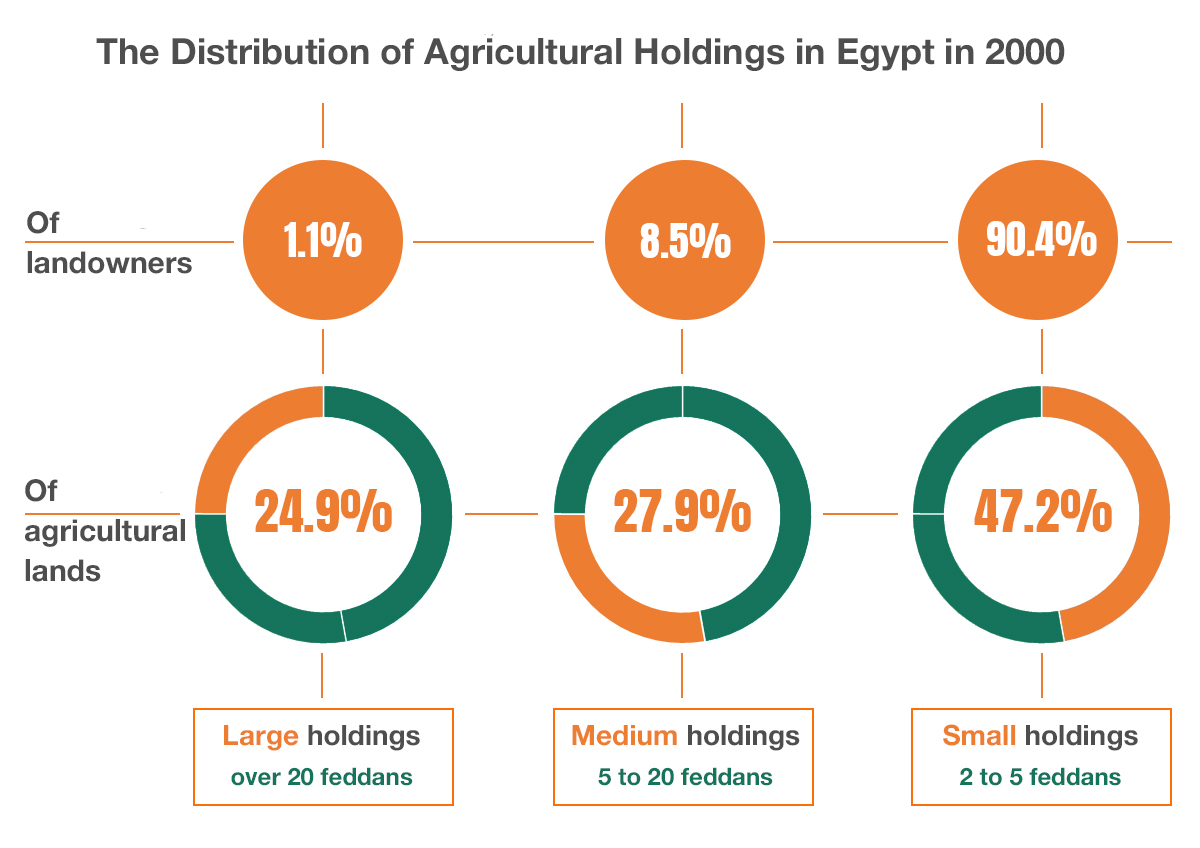

However, the liberal policies adopted by Mubarak were import-oriented through the encouragement of large holdings, which was a clear objective of the 1992 law, reducing small holdings, privatizing lands owned by public agricultural companies, re-pricing certain products, especially fruits, and launching the project of reclaiming one million feddans, which were dominated by big holders and influential state officials, to cultivate export crops. These policies led to the decrease of the areas of possessions of small farmers from 53 percent in 1981 to 47.2 percent in 2000. Meanwhile, medium land holdings (from five to ten feddans) rose to 27.6 percent, held by 8.5 percent of the holders, while 1.1 percent of them held 24.9 percent of the agricultural area, as per the seventh agricultural census in Egypt 1999/2000, carried out by the Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation (the most recent census in this field).

Mubarak regime’s privatization of hundreds of thousands of the reclaimed lands, which were given for cheap prices to businessmen and members of the then ruling national party, as well as Gulf companies amid big corruption scandals, caused widespread anger. The Egyptian-Kuwaiti company of the Kuwaiti Al-Kharafi Group acquired 28 thousand feddans at the desert hinterland to the west of Ayyat for 200 Egyptian pounds per feddan (which is much less than the rental price for the small farmers as defined by the Landlord and Tenant Law). The General Authority for Reconstruction Projects and Agricultural Development Projects facilitated the seizing of businessman Ibrahim Dusouki al-Banna 37 thousand Feddans in the Wadi al-Natroun region. Businessman Suleiman Amer also obtained, between 1997 and 2005, 750 feddans on the Cairo-Alexandria road, which he turned into touristic resorts instead of cultivating them. A report by the General Authority for Reconstruction Projects and Agricultural Development published in May 2017 disclosed that 810 companies that took hold, during the era of Mubarak and after the January 2011 revolution, of an area of 2.8 million feddans of desert lands, invested a big part of them in construction projects instead of agriculture. The report explained that the government’s dues of these lands exceeded 300 billion pounds.

In a report entitled “By the Numbers: Those Who Plundered Egypt’s Wealth,” published in Al-Ahram daily four days after the ousting of Mubarak, engineer Omar al-Shawadfi, head of the National Center for Planning State Land Uses (NCPSLU), announced that the “land mafias” had already seized some 16 million feddans of the Egyptian people’s land during the era of Mubarak. The report also revealed that the government had allocated 100 kilometers of land to the northwest of the Gulf of Suez to five firms, which included four prominent businessmen of the National Democratic Party. They are Ahmed Ezz, the former policy secretary of the party who sold a part of his share to the Kuwaiti Al-Kharafi Group, Muhammad Farid Khamis, Muhammad Abu al-Enein, and Naguib Sawiris.

A report by the General Authority for Reconstruction Projects and Agricultural Development published in May 2017 disclosed that 810 companies that took hold during the era of Mubarak and after the January 2011 revolution of an area of 2.8 million feddans of desert lands have invested a big part of these lands in construction rather than agriculture. The government’s dues of these lands exceeded 300 billion pounds.

During the era of Mubarak, the MPs of the Asyout governorate seized 1500 feddans on the road of Asyout-The Red Sea, while others seized 3500 feddans of a land that was supposed to be allocated for growing a woodland forest in Abnub. In Aswan, too, 28 of the ruling party’s leading figures seized 223 thousand feddans.

Said Khalil (5), the former technical advisor of the Land Recovery Committee, which was established by the current authorities, explains that the illegal seizure of land in the Mubarak era, as well as the inequitable allocations of other lands, were some of the reasons that led to the mounting rage against that regime. He further asserted that several companies are involved in these seizures, such as Kayan that seized 32.642 feddans of the reclamation lands and the “European Countryside”, which seized about 500 thousand feddans.

In parallel, influential figures of the Mubarak regime and MPs were taking control over the agricultural desert hinterlands in the Southern governorates. For Example, the MPs in the Asyout Governorate seized 1500 feddans on the road of Asyout-The Red Sea, while others seized 3500 feddans in Abnub, of a land that was supposed to be allocated for growing a woodland forest. Also, in Aswan, 28 of the ruling party’s leading figures seized 223 thousand feddans.

Favoring Gulf companies

The liberal policies of Mubarak’s regime drove many Saudi, Emirati, and Kuwaiti companies to rush to exploit these lands and turn them into a food basket that serves their countries. The ruling regime launched a major advertising campaign claiming that the new reclamation projects, especially Toshka and Sharq el-Ouwaynat that were launched in the mid-nineties in the south-west of Egypt, were meant to create a new delta in that region to lift some pressure off the Nile delta and motivate the young generations to cultivate vast regions that are irrigated by Lake Nasser in southern Egypt and various wells. However, the numbers of distributed lands show that the biggest beneficiaries from these projects were Gulf companies.

Selling Egypt's Assets: Who Has Ownership?

14-06-2022

The Toshka project (aka The New Valley Project) extends over an area of 540 thousand feddans, making up 5.9 percent of the total 9.13 million feddans of cultivated land in Egypt. Within the project, Kingdom Agricultural Development Company, which is owned by Prince Al-Walid bin Talal, got 100 thousand feddans of land, while Al-Rajhi Saudi company and the giant Emirati company Al-Dahra also got 100 thousand feddans each. In April 2010, the Al-Rajhi company welcomed its first barely crop that was cultivated on an area of 25 thousand feddans, “as the first product of the King Abdullah Initiative for Overseas Agricultural Investment”. The Emirati Al-Dahra Company also announced that it expects its wheat product from the same project to reach 300 thousand tons by 2016. These figures reveal that these three Gulf companies possess 55.5 of the project’s total area.

The Sharq el-Ouwaynat project was divided much in the same way. The Saudi company Rakhaa for Agricultural Investment possessed 24 thousand feddans, of which it cultivates 10 thousand feddans with wheat, Lucerne, potatoes, and corn. The Jannat for Overseas Investment Company, owned by a conglomeration of Saudi agricultural companies, exploits 10 thousand hectares and cultivates them with barely, fodder and wheat. The Al-Akeel Investment Group acquired 21 thousand feddans in Sharq el-Ouwaynat and other governorates. The Emirati Jenaan Investment Company acquired 160 thousand feddans in Sharq el-Ouwaynat and the Minya Governorate in Upper Egypt. The company exploited these lands in the beginning to produce fodder and export it to Abu Dhabi before changing its policy in 2013 into cultivating wheat. Al-Dahra Company possesses 16,185 feddans, in Sharq el-Ouwaynat, which annually produce 50 thousand metric tons of fodder and about 100 thousand tons of wheat yearly.

The Toshka (540 thousand feddans) and Sharq el-Ouwaynat projects that were launched in the mid-nineties in the south-west of Egypt were meant to create a new delta in that region that lifts some pressure on the Nile Valley and motivates the young generations to cultivate vast regions that are irrigated by Lake Nasser and various wells. However, the numbers show that the biggest beneficiaries from this land distribution project were Gulf companies.

Despite the fact that the seizure of lands by companies, businessmen and close associates of Mubarak was one of the causes of the January 2011 revolution, foreign companies, with the exception of Al-Walid bin Talal Company, did not give up the lands they had taken over before the revolution. Al-Walid’s company relinquished 75 thousand feddans of unexploited lands in Toshka, before the army’s National Service Projects Organization (NSPO) bought the remaining share of the company and sued the Kuwaiti Al-Kharir Company for the lands it acquired in Al-Ayyat through suspected corruption and its intention of constructing on them instead of cultivating them. On the contrary, the successive governments after the January 2011 revolution continued to encourage Gulf companies to seize more lands, portraying it as an important inflow of foreign investment into the country. These governments enabled many of these companies to benefit from the lands that were allocated to them during Mubarak’s era, especially in the Toshka Project, as well as buy new lands. The Emirati Jenaan Company, for example, acquired 10 thousand feddans in 2012 from the Ganzouri Government for an animal farm it founded in the south of the Nile Valley.

When El-Sissi assumed power in the second half of 2013, the states that backed his regime and the army were given priority to acquire the lands to be reclaimed, especially those of the 1.5-Million-Feddan Project that El-Sissi had launched in December 2015. Nine months before the project was even initiated, the Emirati Al-Dahra Company expressed its wish to take part in the project, revealing that the Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture had held a meeting with 30 Gulf companies to discuss the project’s implementation.

In January 2017, the Al-Reef al-Masri Company that oversees the project announced that Saudi, Emirati, Kuwaiti and Greek companies have requested to acquire lands, of a minimum of 10 thousand feddans each, within this project.

In August of the same year, the Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture announced that it signed a cooperation protocol with a South Korean company to cultivate 300 thousand feddans in the south east of the Qattara Depression to plant stevia for sugar production since there were no stevia sugar production factories in Egypt. The Egyptian-Kuwaiti Company of Al-Kharafi Group revealed last October that it had built a huge wood factory over an area of 30 feddans in the Minya Governorate, which it had lately acquired. The company is also currently negotiating with the Egyptian government the possibility to acquire 6 thousand feddans near the sewage plants to grow a woodland forest to feed the factory. In December 2018, the Emirati Al-Ghurair and Marban groups announced that they had reached an agreement with the state-owned National Bank of Egypt to reclaim 180 thousand feddans in the west of Minya to plant beets and build the biggest sugar factory in the world.

An increasingly neglected countryside

This trend, based on supporting the big agricultural land acquisitions intended for export, focusing the attention of successive governments on the provision of certain services in the cities whose inhabitants’ rage was a source of disturbance to them, in addition to accelerating the implementation of the liberal economic policies adopted by El-Sissi, have all negatively affected public spending on Egyptian rural areas and agriculture in them.

Although the January revolution drew the attention of the authorities to the necessity of providing services to the people - if only for fear of repeated social and political upheavals, the state still failed to take the rural areas into account, probably because rural rage seemed inconsequential and haphazard.

Many villages complain about the lack or shortage in services, such as the low number of schools as per the number of citizens, the poor quality of the drinking water and its continuous interruption, the absence of sewage systems and medical services, and the lack of industrial projects that can absorb the workforce which often migrates instead to the cities, living in the slums which grow on the cities’ peripheries.

About 76 percent of Egypt’s agricultural lands are located in the Nile Valley and along the Delta, which in comparison to desert lands, enjoy high fertility and easy access to water. Hence, the government’s policies have targeted these lands to overcome the “problem” of small acquisitions.

In 2018, the government waged a wide campaign to remove the rice seedlings in several Delta governorates, as these plants are water intensive. The decision to reduce the areas cultivated with bananas and sugar canes for the same reason aroused fear from dislocating thousands of families that depend on these crops.

One of the major problems facing the farmers is the inability of a significant part of them to repay their debt to the state. The Agricultural Development Bank which started out with the declared aim of solving the farmers’ financial hardships by providing them with loans, with their lands as collateral, has become the monster that haunts them with legal proceedings and lawsuits, even jailing some farmers for failing to meet their debt payments.

Debt write-off for farmers was discussed after the January 2011 revolution, but the former minister of agriculture, Ayman Fareed Abu Hadid, ended this debate in May 2014, when he announced that the farmers’ debts of 3.4 million Egyptian pounds are not to be pardoned.

About 76 percent of Egypt’s agricultural lands are located in the Nile Valley and along the Delta, which in comparison to desert lands, enjoy high fertility and easy access to water. Hence, the government’s policies have targeted these lands to overcome the “problem” of small acquisitions, and to make the most of them through guiding the farmers to specific crops that respond to the country’s internal needs or serve exports.

The government offered several incentives for producing export-oriented crops, such as citruses and potatoes. According to a report by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, the areas cultivated with oranges in Egypt reached 306.9 thousand feddans in 2017 and produced 3.2 million tons of crops, thus competing with Spain as the number-one orange exporter. The government also aims to increase the areas of lands cultivated with aromatic plants to increase exports and bring millions of dollars to the country, through the strategy of redirecting 69 thousand feddans in the Bani Suef Governorate to the south of Cairo to cultivate these plants.

Nevertheless, with the onset of the water crisis, and Ethiopia’s commencement of filling the Renaissance Dam, the biggest dam on the Nile River, the Egyptian government became stricter in implementing its policy of reducing the cultivation of water intensive crops. In 2015, it banned the cultivation of rice in Upper Egypt and the middle and the south of the Delta and increased the fines on those who violated the decision, before it decided to remove the violating farms. In 2018, the government waged a wide campaign to remove the rice seedlings in several Delta governorates, as these plants are water intensive. The decision to reduce the areas cultivated with bananas and sugar canes for the same reason aroused the fears of the thousands of families that depended on these crops as a major source of income, as they dreaded the risk of dislocation.

The consecutive and cumulative liberal policies in the last three decades in Egypt demonstrate the transition of agriculture into a sector that serves major holders and large companies. Meanwhile, the role of the small-scale farmers in this sector is continuously diminishing, or it is restricted to attempts to direct these farmers to serving policies that increase exports. These policies have gravely impoverished the small farmers, as the agricultural yields decline year after year, threatening the profession of farming and the future of villages in Egypt.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Ghassan Rimlawi

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 12/03/2019

1-Feddan is a unit of area. It is equal to 4200 square meters, or 0.42 hectares.

2- This is what the book “Egypt’s Desert Dreams: Development or Disaster” by Dutch researcher, David Sims, warned of.

3- Published on “The Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights” in February, 2010.

4- Professor of Rural Sociology in the Ganoub El-Wadi University in Egypt. The study is published on www.academia.edu

5- An exclusive interview with Assafir Al-Arabi.