This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The protestors of the Hirak, while chanting their slogans and protest songs in unison in the Algerian capital, imposed the loud recognition of football stadiums as major political spaces. The passionately angry chants of football supporters have overflowed from the stadiums onto the streets of cities all over Algeria. The stadium has thus emerged as a center for popular mobilization and the production of politically-charged symbols that resonated profoundly in public opinion, transcending all social categories. The abundance of studies, historical and sociological analyses, and diverse articles by journalists or political commentators covering various aspects of football in Algeria proves the importance of the sport in the socio-political landscape, and a simple internet search can confirm this (1).

In Algeria, as in many countries where entertainment is scarce or inaccessible to the working class, football undoubtedly reigns over all sports, more so in terms of being a grand spectacle rather than a sport for mass participation. While large stadiums have been built throughout the country since the 1970s, the infrastructure for training and playing spaces in the neighborhoods is scarce and far from meeting the expectations of a neglected youth. The investment in local sports facilities is indeed very limited, negligible in comparison to the needs. In working-class neighborhoods, football is predominantly played in the streets or in vacant lands.

Despite the lack of a public policy for the development of sports activities, the Algerian public's enthusiasm for the sport remains strong. Every Friday, the stands of every stadium in the country become equally packed with supporters, especially during the matches of the national team, which are marked by a passionate intensity that overflows into the public space, filling it with an electrifying energy.

Football's origins and anti-colonial emancipation

The enthusiasm for this sport, its political significance, and the emotional charge it carries are integral parts of Algeria’s history. Football played a significant role in the resistance to colonialism. The first all-Algerian sports clubs emerged during the height of colonial domination in the early 20th century, a few years before the arrogant celebration of a century of colonization in Algeria in 1930.

Although other sports clubs dispute its precedence, such as the Mouloudia Club of Oran (MCO) or the Constantine Sports Club (CSC), which claim earlier founding dates, the highly popular Mouloudia Club of Algiers (MCA), officially established in 1921, is considered the oldest Algerian football club.

These clubs, which quickly multiplied across the country, were named after their cities of origin and often made references to Islam to distinguish themselves from European teams composed mainly of "pieds-noirs" (French colonizers born in Algeria), with whom the competition was not only athletic but also carried deeper social implications. And thus, football became an active factor in the formation of a modern national political consciousness.

In fact, even before the founding of the Algerian Muslim Scouts Movement (the first public school for nationalist youth) in 1935, football clubs served as the initial structures for political expression, with some more openly anti-colonialist than others. Naturally, the colonial authorities understood the danger that these gatherings could pose and attempted through various means to prevent football clubs from becoming hotbeds of nationalist sentiment. Consequently, a number of constraints were imposed on these clubs, such as the requirement to integrate one or more non-Muslim players into their teams and to reserve the use of their premises exclusively for activities directly related to sports (2).

The clashes between "indigenous" football supporters and the pieds-noirs (North African French colonizers) in the strictly segregated stands often mirrored the conflicts between players on the pitch (3). The victory of a North African team (4) over the French team in a friendly match in Paris in September 1954, two months before the start of the national liberation war on November 1, 1954, was perceived as a prophetic event by many independence aficionados (5).

The matches played during the early months of the liberation war were marked by increasingly violent clashes between "indigenous" (Algerian) supporters and pieds-noirs (Europeans) and often escalated into riots. Following the call from the National Liberation Front (FLN), Algerian sports clubs permanently withdrew from all official competitions.

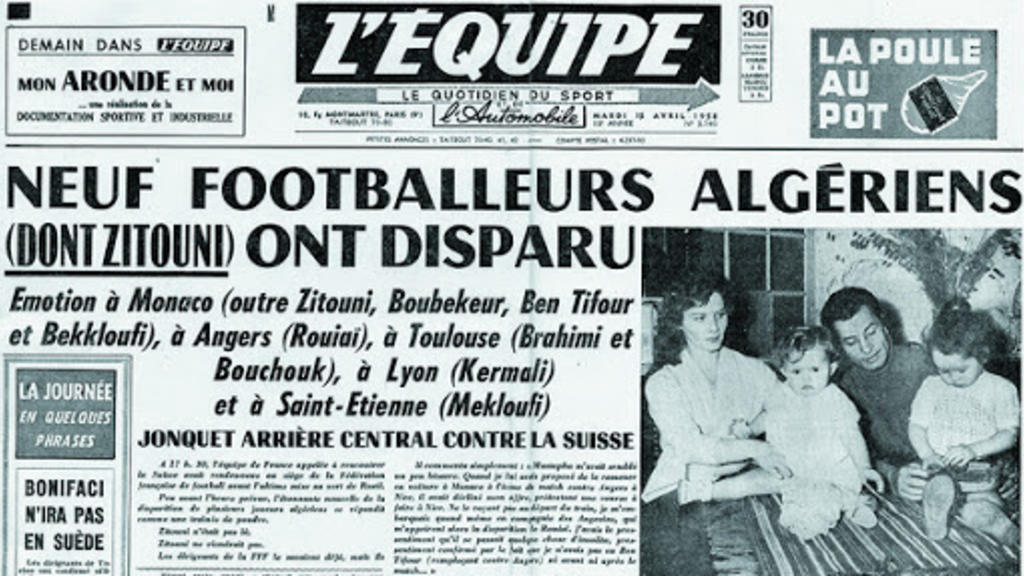

However, politically, the most remarkable victory for the FLN was the defection of well-known Algerian footballers playing in major French clubs (6) in April 1958. The FLN’s football team, known as the ALN, had been established a few months earlier in 1957, at the height of the liberation war, and it became the national team of the resisting Algeria. The team played nearly 90 matches worldwide until 1962 and served as an effective lever for international propaganda. For the Algerian sports public, the team became a unifying symbol of the reclamation of a violated dignity. Throughout the years, it has created unparalleled enthusiasm and a deep attachment to the national team that persists to this day.

The stadium as an outlet and protest forum

This period in which the national team and resistance football were founded remains vivid in collective memory, but the post-independence reality bears little resemblance to that treasured legacy. In fact, the sport was generally considered secondary by the authoritarian regime that had emerged from the power struggle during the summer of 1962 (7). While successive leaders were interested in the political benefits of the game, in terms of the popularity of the game and the social base it provides, they refrained from investing in its development. The generalization of education represented the main strategy of successive administrations towards the youth. As a result, Algerian football was founded without a real sports project, while the 1977 reform was the only genuine attempt to organize the sport and lay the foundations for infrastructures that could meet the expectations of a young and rapidly growing demographic.

The victory of a North African team over the French team in a friendly match in Paris in September 1954, two months before the start of the national liberation war on November 1, 1954, was perceived as a prophetic event by many independence enthusiasts.

Following the call from the National Liberation Front (FLN), Algerian sports clubs permanently withdrew from all official competitions. The most politically remarkable victory for the FLN was the defection of well-known Algerian footballers playing in major French clubs in April 1958.

This “socialist-inspired” reform aimed to connect the most important sports associations to public enterprises in order to provide them with the necessary means for the development of their activities. While this justification is undoubtedly sincere, there is little doubt that the intention of the decision-makers at the time was primarily to deprive the poorly organized political forces of a means of influencing the youth. Indeed, the end of the reign of Houari Boumediene, who died in December 1978, coincided with the emergence of identity tensions in Kabylia, following a policy of Arabization that disregarded the historical specificities and socio-cultural particularities of the country. As a result, during the Algerian Cup final in June 1976, President Boumediene, who was present in the official VIP box, was booed by supporters of the Jeunesse Sportive de Kabylie (JSK).

Since that unprecedented event, football stadiums, once rare spaces for gatherings and free expression, gradually transformed into echo chambers of popular discontent. The outstanding performance of the national team during the 1982 World Cup, and the subsequent deceit (8) it was subjected to, briefly ignited a collective fervor in a time of accelerated degradation caused by the deteriorating socio-economic situation since the fall of oil prices in 1986. In this period of mounting tension, the presence of officials in the stadiums was met with ridicule and insults from football fans in the stands. During the 1980s, football matches, especially derbies that reignited rivalries extending beyond mere sports competition, often culminated in anarchic demonstrations and confrontations, at times escalating into highly violent clashes with the security services.

Tensions manifested at the power summit in the beginning of October 1988, between supporters of a neo-liberal “infitah” (openness) and defenders of the status quo, resulting in “spontaneous” demonstrations that attracted thousands of young people across the country. Against a backdrop of prevalent unemployment, shortages of all kinds, and price hikes, these upheavals expressed the conditions endured by the working classes of a society oppressed by the rule of the single party. These upheavals were violently repressed by the army and the political police in a horrific carnage that led to several hundred deaths, most of whom were very young people, accompanied by atrocious human rights violations.

Between political police and oligarchs: manipulation and diversion

Since that event, stadiums have been bastions of popular political expression, serving as a mass outlet for the youth who chant their anger and despair in the form of insults directed at all authorities. The coup d'état on January 11, 1992, which interrupted the democratic process that was initiated following the events of October 1988, marked the beginning of a long period of hyper-violence and bloodshed. During the "dirty war" against civilians, which lasted until the early 2000s, tens of thousands of Algerians died in questionable circumstances (9). The perpetrators of these crimes against humanity have largely remained unknown, and those of them who were identified enjoy total immunity. Throughout this harrowing period, the football stands echoed provocative chants glorifying some leaders of terrorist groups that claimed to represent Islam. The supporters were unaware at the time that these “Emirs” were, in fact, infiltrators or agents planted by the political police. The fact would become clear to them only later (10).

Against a backdrop of widespread unemployment, shortages of all kinds, and price hikes, upheavals erupted in 1988, reflecting the conditions endured by the working class of a society oppressed by the rule of the single party. These upheavals were violently repressed by the army and the political police in a horrific carnage that led to several hundred deaths, accompanied by atrocious human rights violations.

Since halting all matches was an impossible task during that period of violence in the 1990s, the authorities resorted to a strategy of exerting control and attempting to channel the outrage of passionate football fans. To achieve this, political police employed loyal individuals who were aligned with their political agenda to seize control of the Algerian Football Federation (AFF) and football clubs. The police also made efforts to establish communication channels with the fervent fanbase, known as the “tifosis”.

However, infiltrating and manipulating these groups of supporters proved to be a complicated task. These grassroots, informal groups comprise young people from neighborhoods who know each other very well. So despite all the police measures, officials who attended games in the stadiums every Friday had to endure the barrage of insults and curses shot at them by a furious, politically charged public.

In the early 2010s, in line with the privatization policy that resulted from the rescheduling agreements with the IMF in 1994 and 1995 and in the predatory business climate of the Bouteflika era, the authorities decided to professionalize football for the top football clubs in Algeria. Oligarchs became the heads of the clubs, and the political police relied on their proven corruption to absorb the head supporters and tune down the wrath of young fans. Despite the tremendous injection of capital into the game, this professionalization of clubs and the erratic management of the complicit “businessmen” have brought absolutely nothing in terms of the quality of national Algerian football and have not led to reducing the supporters’ anger.

These millions of football fans and “tifosis” do not align themselves with any particular opposition group but rather only express their love for their country. These irredentist and diligent young people believe that meaningful progress cannot be expected of a brutal and completely corrupt military-police dictatorship.

Nevertheless, the decision-makers, anxious to divert attention from a furious public that has grown weary of the mediocrity and incompetence of the rulers, find in the unwavering support of large segments of the population for the national football team an effective lever for improving the general climate of the country through tactics of distraction.

A tifo displayed as Mouloudia Club enters the field

Thus, in November 2009, the regime did not hesitate to exploit the strong indignation of the public following the violence suffered by the Algerian national team in Cairo. The authorities of the two countries did absolutely nothing to calm the poisoned atmosphere (11). On the contrary, Egyptian and Algerian media vindictively escalated the hostility. The Algerian air fleets, civil and military, were mobilized, as per President Bouteflika’s instructions, to transport thousands of angry supporters to Sudan, which hosted the away match. The victory achieved in that match was an ephemeral moment of communion between the people and the decision-makers. The successes of the "Fennecs" (desert foxes, as the players of the Algerian team are called) during the 2013/2019 period, which culminated in their coronation at the African Cup, were celebrated by the public in bursts of collective joy rarely seen since the country’s independence.

The stages of irredentism

However, these rare moments of euphoria were short-lived, as the stadiums remained boiling cauldrons where the pent-up anger of the disadvantaged youth exploded unreservedly. This anger was not solely directed at the country's leaders. Known for their unwavering solidarity with Palestine, football supporters never hesitated to voice their discontent (12) and openly criticize those who have turned their backs on the Palestinian cause (13).

The fans of USMA sing for Palestine and condemn those who have abandoned the Palestinian cause

In the early 2010s, in line with the privatization policy and in the predatory business climate of the Bouteflika era, the authorities decided to professionalize football for the top clubs in the country.

Oligarchs became the heads of the clubs, and the political police relied on their proven corruption to absorb the head supporters and tune down the wrath of young fans.

The popular demonstrations of the Algerian Hirak, which started on 22 February 2019 and quickly spread to cities across the nation, provided a platform for the protesters to showcase their remarkable creativity through slogans, songs, and banners. However, what caught the attention of observers initially was a song titled “La Casa d'El Mouradia ” (14), chanted in unison by people of all classes and social segments.

The song “La Casa d’El Mouradia” sung in unison by USMA fans

This song, memorized by heart by many, drew inspiration from “La Casa de Papel ,” (15) a popular Spanish TV series. The chant was created by supporters of USMA (16), a widely popular football club based in the capital. The club's “tifosis”, known for their inventive stadium performances, excel in combining mockery, sarcasm, and political protest.

The COVID-19 pandemic, exhaustion, and violent repression caused the street demonstrations to dwindle in the major cities, but the chants of football supporters in “Darja,” the language spoken by the capital's residents but understood by all Algerians, continued to echo the despair of a politicized and intelligent youth (17) who realize what is at stake and know that the full weight of the responsibility lies upon the ruling class.

These grassroots, informal groups of supporters comprise young people from neighborhoods who know each other very well. Despite all the police measures, officials who attended games in the stadiums every Friday were the target of a barrage of insults shot at them by a furious, politically charged public.

These millions of football fans and “tifosis” do not align themselves with any particular opposition group but rather only express their love for their country. These irredentist and diligent young people believe that meaningful progress cannot emerge from a brutal and corrupt military-police dictatorship. Who can dispute the argument that this senile regime, resistant to any form of development, offers the youth nothing more than the catastrophic escape into drugs or illegal exile to Europe, where they face countless risks? It is obvious that the immoral, incompetent figures at the head of the regimes are responsible for the bleak future that awaits the youth.

Football in Egypt: Where People Find Solace

08-06-2023

Through football, their only open platform, Algerian youth relentlessly express their rejection of the injustice and contempt they are subjected to. This sport which has served as a vehicle for decolonial rebellion and the pursuit of freedom and dignity continues to act as an amplifier of the political demands of the Algerian people.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabah Jalloul

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 30/05/2023

1- In this article, the author primarily refers to the study by the late Djamel Boulebier published in French in 1999 entitled "Football, urban life and democracy", Insaniyat Magazine. Online since November 30, 2012: DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/insaniyat.8324

2- See Football in the Algerian War - Philip Dine and Didier Rey. https://tinyurl.com/mrx7vyvf

3- "The stadium quickly became a "microcosm of ethnic clashes," as per a report from the governor of Constantine addressing the violence provoked by supporters of the Muslim club of the Jeunesse Sportive Djidjellienne in 1937, in: From a propaganda tool to a reflection of the Algerian War: The National Liberation Front’s football team, 1954-1962. Vincent Jacquet - Bulletin de l'Institut Pierre Renouvin 2018/1 (N° 47)

4- Alongside the legendary Ben Mbarek, the North African team lined up the Algerians Mustapha Zitouni, Abdelaziz Bentifour, Mokhtar Aribi, Abderrahmane Boubekeur, Abderrahamane Meftah, Rachid Belaid and Said Haddad, the Moroccans Abderrahmane Mahdjoub, Mohamed Abderrazak and Salem Benmiloud, as well as the Tunisian Kassem Hassouna.

5- Yves Gastaud – University of Nice: https://tinyurl.com/8nnm2sv7

6- The National Liberation Front team at the heart of the struggle for Algerian independence: https://t.ly/2_6k

7- A talk by Muhannad Amer Ammar at the symposium organized by the “Ecole Normale Supérieure” in Lyon in June 2006 on the political crisis after independence in the summer of 1962: https://t.ly/M3S

8- On the peculiar circumstances that accompanied this event, see: https://t.ly/gapl

9- See Algeria: The Death Machine: https://algeria-watch.org/?p=52437

10- See Report No. 19 of the 2004 TPP: https://www.algerie-tpp.org/tpp/pdf

11- See “The rigged matches of dictatorships” Algeria-Watch, O. Benderra 13.12-2009: https://algeria-watch.org/?p=65722

12- USMA supporters in 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3rosmpLneMI

13- Algeria apologizes to Riyadh for a banner raised in a stadium: https://t.ly/KSK4

14- The complete chant is transcribed in Omar Zelig’s article in the folder “The 2019 Uprisings: A Constitutive Creativity”, published in Assafir Al-Arabi: https://assafirarabi.com/en/36326/2021/02/28/an-incomplete-algerian-symphony/

15- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZVSEBEUcTY

16- https://www.usm-alger.com/site/index.php/histoire

17- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ncWc_IpcVv0