This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

This study aims to analyse the nature of the relationship between public policy, urban ecology, and social relations in some of Casablanca’s neighbourhoods, Morocco’s economic capital. The expulsion of shantytown and old city residents from an urban milieu that pushes social relations into new urban forms (apartment buildings), where mass housing prevails, has negatively affected social relations. Security concerns and the prevalence of individual values have, in turn, shaped new urban forms. Likewise, as families in big cities tend to close in on themselves, one notices similarities between the violent and bloody uprisings and the growing production of what is called “enclosed residential enclaves”.

Introduction

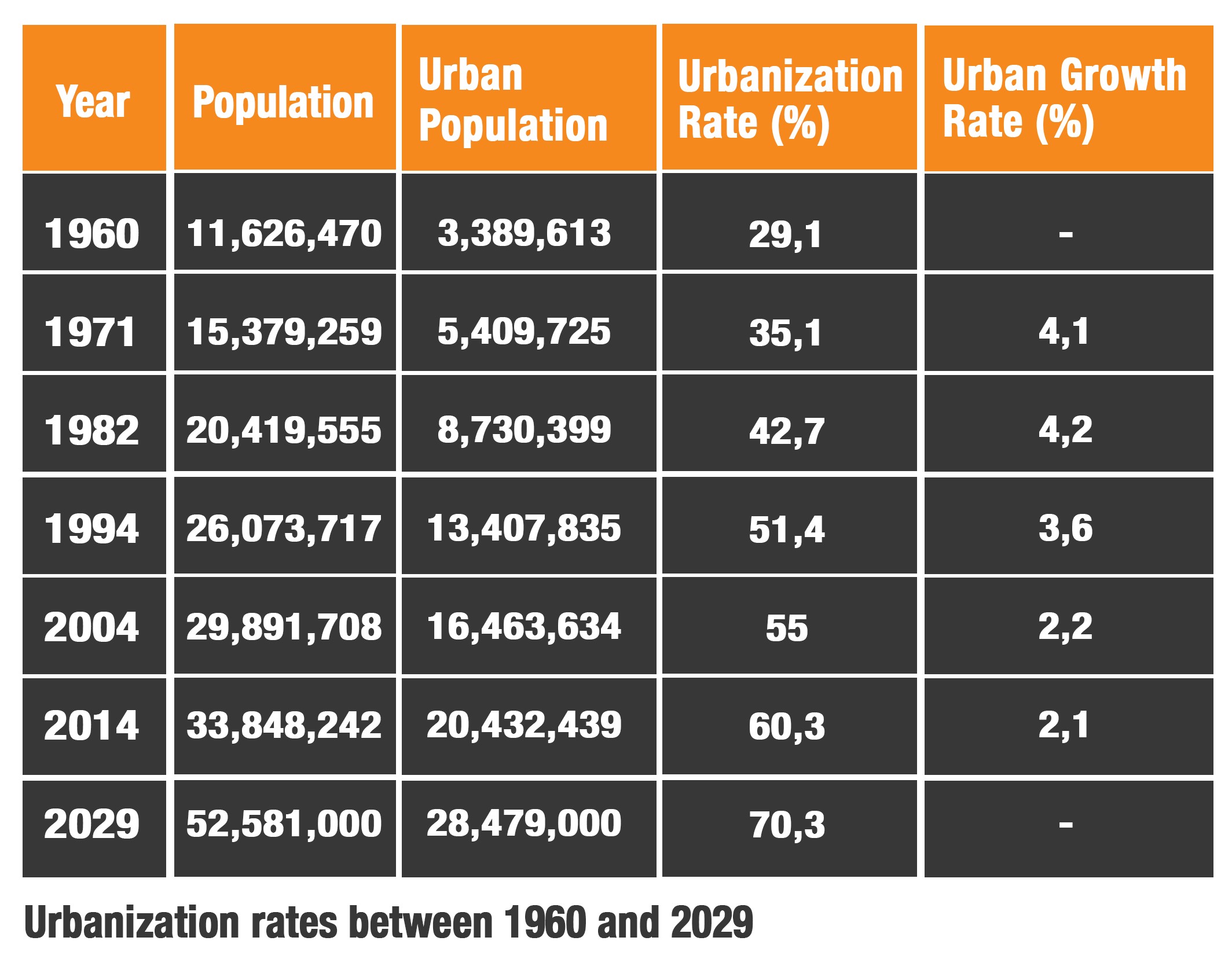

In the early twentieth century, and before the colonial administration imposed its rule over the country (1912-1956), urbanization rates in Morocco were small – 8 percent. In a period of fifty years (1960-2014), urbanization leaped from 29 to more than 60 percent – and, according to official projections by the Office of the High Commissioner for Planning, could reach more than 70 percent in 2030. The inhabitants of the biggest seven cities make up more than 41 percent of the total urban population – 25 percent of the population (1) in 2014.

Official statistics indicate that demographic growth in big cities, like Casablanca, is basically carried out through organic development, and doesn’t rely on rural immigration. These demographic changes and their ensuing social and urban impacts have produced an urban society with a new individualist culture, values, and behavioural patterns, indistinguishable from the new capitalist system imposed by the colonial administration. These are also a result of the ecological form of large human masses clustered in a restricted area, called the metropole or mégapole. Ever since the early twentieth century, colonial intervention, along with the implementation of a new economic system, have resulted in an intensive and rapid process of urbanisation (rural immigration and concentration into cities). However, the rural or tribal concentration would not be reproduced in urban spaces. Spatial gatherings have always been based on relatively small units. Until the beginning of the 1980s, cities grew in a spontaneous manner, and have theoretically submitted to models designed in the colonial era (1952-1955).

The city as a political stake

Urban politics took off with the early 1970s, in a context of the five-year economic and social development plan (1973-1977). Due to the little experience, competence, frameworks, and weak financial resources, the state’s intervention was slow and limited to preparing housing plans for low-income social groups. No comprehensive planning of cities was developed in neither short nor mid or long terms. However, in 1981, the city would suddenly, and for the first time, become a huge political stake. That year would stand out for the social revolts that broke out following the union call for a general strike, which resulted in tensions in large, medium, and small cities (2). Those social protests shocked politicians and the national public opinion due to their violent, rather deadly, repercussions – as the military intervention would result in hundreds of victims.

Right after the revolt, a political arrangement for the urban community would be rethought. It would be based on putting a stop to physical violence as a sole means for social repression (arrest, terrorization, assassinations, imprisonment for the crime of expressing one’s views, isolating scientists and preachers, confiscating newspapers, discontinuing magazines…) and new “modern” approaches would be prepared instead.

Being young at old Sidi Mumen, Morocco

29-03-2015

Casablanca: From High-Rises To Slums

23-10-2013

Primarily, these new approaches consist of ensuring an improved surveillance of the population, carried out through tools of urban planning (the Administrative Plan for Urban Development 1981-1984 and Collective Development Plans 1984-1989). The state would begin to implement an intensive policy of social housing, hoping to achieve social integration processes to populations considered “groups that pose danger” (3) to the overall situation. Between 1983 and 1987, more than 9,000 housing units would be constructed in Casablanca at lightning speed, in order to accommodate shantytown families from the Ben Msick neighbourhood, which alone housed more than 80,000 people in 1982.

In 1981, the “city” in Morocco would suddenly become a huge political stake. That year would stand out for the social revolts that broke out following the unions’ call for a general strike, which shook politicians and the national public opinion as a result of their violent repercussions, as the military intervention left behind thousands of victims.

Urban development plans would launch fierce campaigns against neighbourhoods considered to be hubs for violent social upheavals. A plan was thus prepared to demolish a large number of houses to shrink the demographics and expand the highly crowded urban space. Demographic density and visibility in urban spaces were some of the standards that justified the state’s intervention in the neighbourhoods that were home to the rebellion.

In this authoritarian political context, none of the concerned actors (architects, contractors, land owners, the population…) were brought in to co-create the new construction documents. Even apartment owners couldn’t organize a collective protest, although their new homes were also facing demolition orders, so that public facilities would take their place, according to urban development plans for 1987. As such, spatial (neighbourly) proximity was rendered powerless in organizing social protests.

Weak control over urbanization

The state, along with all its sectors, doesn’t play an active role in urban planning, controlling urbanization, or in actually directing it; (4) internal urban dynamics go beyond the state. Shantytowns would only grow in big cities following 2011, which coincided with the Arab Spring; the state apparatuses would choose not to intervene with violence against the nationals who violated state laws, for political and security reasons. Shantytowns would grow at a fast rate and the public space would be pervaded by popup markets of fruits and vegetables and fishes, as some streets filled with street vendors. Madiouna Street, one of the largest streets of Casablanca, became a vendors’ street, rather than a mere passage for cars. More than a year had to pass by, following the shrinking social unrest that is, for the local authorities to be able to control the situation. Street vendors not only proliferated popular neighbourhoods, but also “nomad” vendors challenged local authorities by planting their products in the streets of the city centre.

The urban development plans launched a brutal campaign against the neighbourhoods considered hubs for the violent social eruption. A plan was put in place to destroy a large number of houses to guarantee reduced demographic density and the expansion of the highly populated urban fabric.

Although development plans have been prepared, the state laws are still violated in terms of construction; it tries to catch up to urbanization by building facilities, destroying shantytowns, restructuring large neighbourhoods, and destroying other informal settlements. While authorities dismantled older shantytowns, they would find themselves faced with newfound unplanned areas, be they intended for housing or labour.

Towards abolishing shantytowns?

In its general policy, the state launched a program titled “Shanty-free cities” in 2004, with a financial cap of nearly 32 billion dirhams to completely eliminate shantytowns in cities, and to enable 300,388 households housed in those spaces to find proper housing. In December 2015, 55 out of 85 cities were announced shantytown-free. The households that previously lived in shantytowns and have received proper housing, or are already promised places under construction, make up 82 percent of that population.

The national research (5) to evaluate the impact of fighting unplanned housing (shantytowns) has revealed “a clear improvement in every index related to the living conditions of the families that have benefitted from the Shanty-free program, whether in access to education, healthcare, social services, or infrastructure, as well as in improving children’s living conditions”.

Shantytowns would grow in big cities following 2011. The state apparatuses would choose not to intervene with violence, for political and security reasons. Shantytowns would grow at a fast rate and the public space would be pervaded by popup markets of fruits and vegetables and fishes, as some streets filled with street vendors.

The research noted a reduced poverty rate of 28.3 percent as opposed to 48.7 percent of households in previous shantytowns. Furthermore, there was a marked drop in unemployment rates, from 27.3 to 23.5 percent, along with a higher rate of enrolment at schools or vocational institutes, exceeding 96 percent among children and young people aged 5 to 14.

While the official report concludes with a positive evaluation, it fails to address the spatial marginalization of these fragile social groups, just as it disregards the nature of the new social relations that the adopted housing policy produces.

New special social relations have emerged with the demographic growth, urban expansion, and the increasing and different urban problems (expulsion of the inhabitants who live in shantytowns into the suburbs, lack of work opportunities, unemployment, housing crisis, delinquency, divorce, lacking a sense of safety…) have been proportionately growing along social discrimination and striking spatial segregation. This new social situation encourages the spread of new values related to individualism and financial rivalry, leading to the creation of new social relations marked by restraint, caution, and introversion. As such, neighbourhoods have ceased to be that space that translates into some form of a collective, or that territorial unit defined by strong social links.

Collective narratives (as heard through field testimonies), would hold a scent of nostalgia, tears, and longing for a past long gone. Everyone remembers the time when harmonious and perfect social and religious relations prevailed; a time when “the door to my house remained open night and day”. Now, a house door symbolises borders that must not be crossed. It demarcates a microcosm, and becomes an element of separation and an inhabited space that protects family intimacy. An ever-closed door expresses the desire to keep all strangers away from the family.

The word “distance” was another recurrent theme in the interviewees’ talk. One seventy-year-old widower, who used to live in the old city, said: “Back in our days, respect and solidarity prevailed. If one day you couldn’t prepare your own dinner, your neighbour would invite you to share their food. Today, a neighbour could easily barbecue right before your eyes and leave you to consume no more than the smell… Neighbours no longer care for you. The manners of neighbourly living are gradually disappearing with this generation.”

A city is more than the houses, roads, or social and economic facilities inside it. It is also the networks of social relations weaved among its residents. Manifestations of urbanization indicate a radical change in the overall patterns of social life. The more a population grows, the more distinct and heterogeneous it becomes. This translates into disappearing kinships, weakened neighbourly relations, and a collapse of the traditional foundations for social cohesion, whereby social relations become impersonal.

New social relations appeared, especially with the demographic growth, urban expansion, and the increasing and diversifying urban problems, which are proportionate to the increasing social discrimination and striking spatial segregation. Neighbourhoods stopped being that space that translates into some form of a collective, or that territorial unit defined by strong social links.

The national research on social bonds (6) carried out by the Royal Institute for Strategic Studies (Rabat) indicates weakened neighbourly relations and the prevalence of values connected with introversion, and this does not concern big cities only. In our daily lives, we notice households clearly and increasingly inclined to search for “personal isolation”. The prevalent social logic is to create distance among neighbours, or with the “other”, in general. Establishing a buffer zone, or a distance from the neighbours, has been imposed as a positive value by urban ecology. Hence, when an individual tries to open up to others by making small talk and asking some regular questions, that is, not intimate ones, they’re labelled as “intrusive”. Anonymity imposes lack of confidence, and so creates distance among neighbours.

Solidarity and cooperation

In parallel, as individualism prevails in big cities, leading to the retreat into the family, all households agree that neighbours in general are cooperative in times of death or illness. In such difficult times, neighbours who live in buildings or in one of the new neighbouring streets prepare food and welcome mourners. The elected local council also seeks to provide large tents to accommodate all the neighbours and relatives of the deceased.

Sometimes the neighbours experience exemplary forms of solidarity, following the collapse of a house, a fire or a flood, or after the state apparatuses threaten to demolish some shanty houses. While waiting for help to arrive, some young men might go as far as risking their own lives to save their neighbours. However, as soon as the tragic event is overcome, life goes back to normal…(7) This kind of social solidarity happens naturally and spontaneously. Some neighbourhood associations have also been trying to create and strengthen social relations among neighbours, but their impact remains quite limited.

Conclusion

The issue of social bonds appears nowhere in the discourses of political parties. They are nowhere to be seen in public discussions or conversations, nor among architects, within the Ministry of Housing, local authorities, or media. The government’s main concern consists of accomplishing and building social housing as well as eliminating all shantytowns in Moroccan cities, without considering the social and political implications of their interventions, nor the outcomes of the new social relations that are coming into being in these new marginal areas.

On the other hand, the question of social bonds and living spaces had been raised in high-level decision-making centres. In 2009-2011, the Royal Institute for Strategic Studies in Rabat financed a research, initiated by the royal advisor Mezyan Belfkih, on social ties across the nation. Likewise, the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council (a constitutional establishment) organized a workshop on living spaces.

Moving from an authoritarian political system that produced violent rebellions in the 1980s into a system that seeks to “open up” to society has resulted in new collective nonviolent actions (protests, rallies, sit-ins…) in public spaces in the late 1990s. One could consider a sit-in, protest, or public gathering as new spaces wherein social ties could be created, as opposed to the general “coldness” of social relations in big cities.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 28/11/2019

1- As per the latest official census of housing and population carried out by the Office of the High Commissioner for Planning in Rabat, 2014.

For further reading, see Rachik, Abderrahmane. Protest Movements in Morocco: 2- From revolt to protest, trans. Hussain Sahban, a report in Arabic and in French, Rabat, 2014.

3- Besides, a religious policy would be implemented, presumed to guarantee surveillance over Islamic movements and independent scientists, as well as “recruit” religious scholars.

4- Rachik, Abderragmane. Politique urbaine et espace périphérique à Casablanca. Sarrebruck: Éditions universitaires européennes, 2016.

5- For the results of the national research to evaluate the impact of fighting inadequate housing carried out by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Policy, see http://www.maroc.ma.

6- Institut royal des études stratégiques, Le lien social au Maroc, an unpublished investigation, Rabat, 2012. (A research the writer has participated in between 2008-2011)

7- Wealthy social groups have been resorting to party planners to receive mourners during wakes.