This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Tunisia's area and its natural resources are both limited, especially if we compare them with the country’s eastern and western neighbors: Libya and Algeria. Tunisians have always said that their untold wealth is human resources and “gray matter” (that is, the brains of citizens), as late Tunisian President Habib Bourguiba used to say. Indeed, natural resources are often limited, but so is the population. Nevertheless, a large part of the population has a high level of education and an epistemic capital that allows for the proper exploitation of these resources and the exploration of other potential ones. This text will address only three natural resources due to their importance and/or their abundance and/or their impact on the economy, environment, and society. These resources are water, phosphates, and fossil fuels.

Water: the ghost of thirst

In recent years, "green" Tunisia has been teetering on the edge of water poverty. This dangerous situation, which might worsen in the upcoming years, is due to several reasons, some of which are natural-climatic, while others are the responsibility of humans, whether these are rulers or ruled.

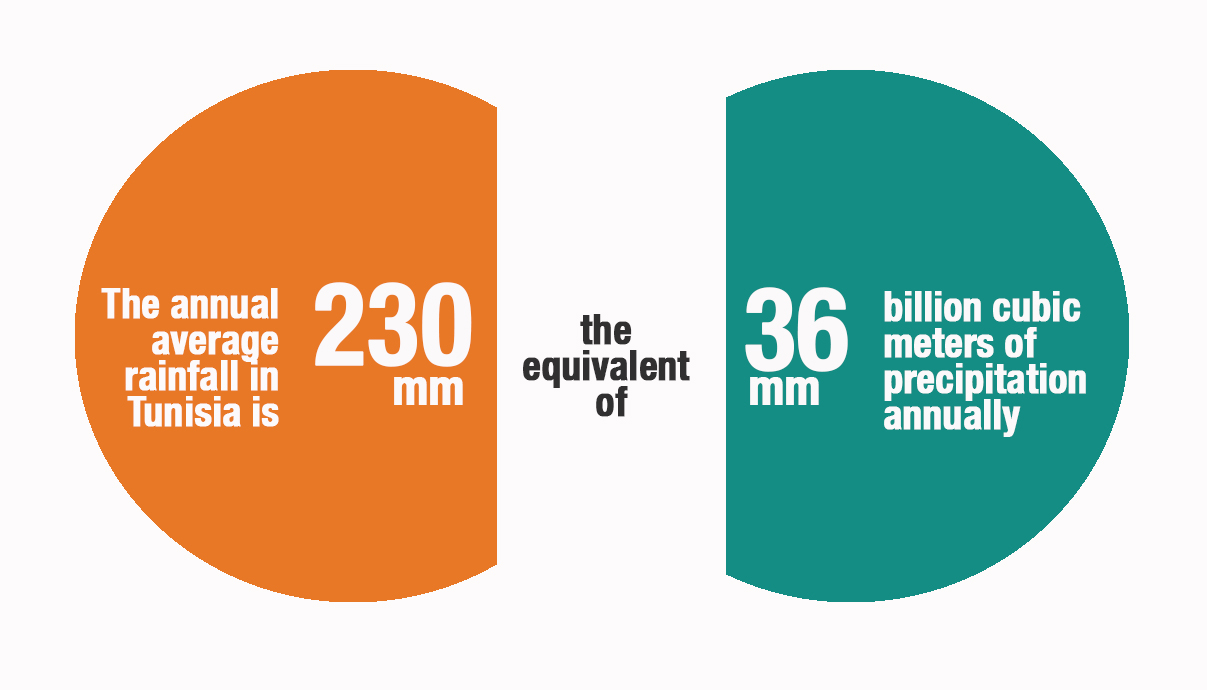

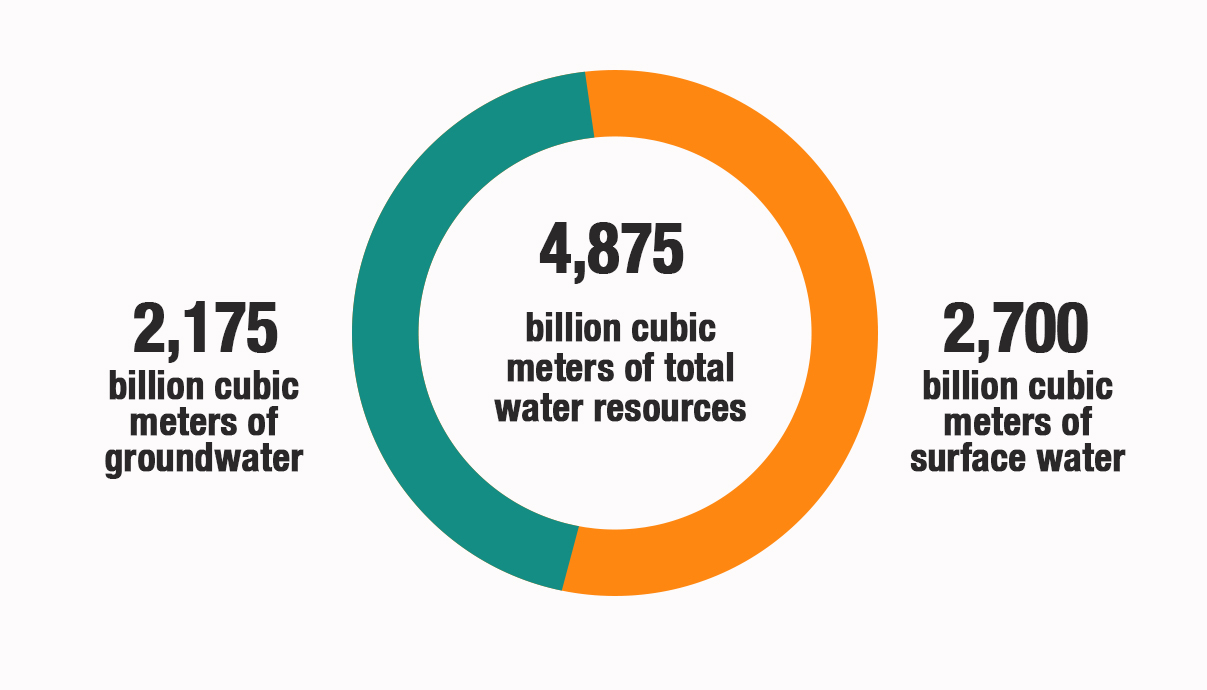

The average annual rainfall in Tunisia is 230 millimeters per year, which is equivalent to 36 billion cubic meters of precipitation annually. Moreover, arid and semi-arid climate dominates most of the country. Tunisia has water resources estimated at 4.875 billion cubic meters, of which 2.175 billion cubic meters are from groundwater, and the rest is from surface water. Surface water storage is based on a hydraulic infrastructure that consists of 40 dams, nearly 1,000 mountain lakes, and 400 mountain dams, giving Tunisia a storage capacity of approximately 3 billion cubic meters. There are 16 water treatment plants, 12 underground water desalination plants, and one seawater desalination plant. Per the official figures provided by the Société Nationale d'Exploitation et de Distribution des Eaux (SONEDE; National Company of Water Exploitation and Distribution), the percentage of Tunisians connected to the potable water supply network is 100 percent in urban areas and 97 percent in rural areas. In conclusion, water resources are limited, but there are considerable efforts, plans, and a hydraulic infrastructure to increase the volume, storage, and distribution of these resources. Where do the problems lie then? And why does water poverty threaten Tunisia?

One of the main problems associated with water availability is the economic policies adopted by the government. Since the late 1960s, the government has chosen to rely on a “light” and diversified economy based on the export of phosphates, agricultural materials, light manufacturing industries, and low-cost beach tourism. This policy provided jobs and brought in large revenues in hard currency, but this had its high environmental, especially aquatic, costs.

There are three main problems; the first of which concerns rainwater harvesting systems such as dams and mountain lakes. Despite enormous investments and national strategies, there are significant shortcomings in this area. The storage capacity of dams and similar facilities is still insufficient to accommodate the precipitation waters, which are largely wasted in vain and into the sea or bogs, despite them being already limited. Even this limited storage capacity is not guaranteed, as many Tunisian dams lose up to 40% of their storage capacity due to sediments and lack of maintenance.

The second major problem is the depletion of water resources due to the economic policies adopted by the government. Since the late 1960s, the government has chosen to rely on a “light” and diversified economy based on the export of phosphates, agricultural materials, light manufacturing industries (mostly owned by foreigners), and low-cost beach tourism. This policy created economic dynamism, provided jobs, and brought in large revenues in hard currency, which had high environmental, especially aquatic, costs.

The third major problem is the distribution of potable water networks and irrigation networks. Water distribution does not pose a big problem in urban areas, as SONEDE connects homes, shops, and factories to the centralized treatment network. However, the so-called water societies/ associations are in charge of linking houses and agricultural lands outside the cities to the water supply networks. They are councils made up of representatives of the residents of the relevant area, who supervise an electric water pumping plant and take charge of collecting invoices and maintaining equipment. However, neither the experience nor the organization of the supervisors of these councils is suitable for managing facilities of such importance, which results in a huge water waste. Moreover, water distribution among agricultural lands is usually affected by political loyalties (in the era of the dictatorship), nepotism, and family and tribal affiliations. According to official figures, there are only 400 “exemplary” associations out of 2,500 associations, which means that more than 80% of the structures that control the distribution of more than 80% of water have problems ranging from lack of maintenance, misconduct, and corruption.

Phosphates: a blessing and a curse

Phosphate is the most important natural and mining resource in Tunisia in terms of financial returns and the volume of reserves available. It has a special place in the country's modern history, as its story began with the French occupation of Tunisia and continues to this day. Phosphate mines contributed to building the Tunisian trade union movement and in assisting the national movement and the armed resistance to colonialism. This natural resource later played a leading role in providing the financial resources to build a post-independence Tunisia.

In 1885, four years after the occupation of Tunisia, the French geologist Philip Thomas discovered the presence of significant amounts of phosphate in the Metlaoui area in the southwest governorate of Gafsa. It was not long before the colonial authorities began to plunder this resource. In 1897, they granted a license to a French company to explore and exploit phosphates on a precondition that it pays for laying a railway between the mines and the seaport of Sfax, in the center of eastern Tunisia. The Phosphate Company and the Gafsa railways started by digging tunnels for underground mines in the Metlaoui area in 1899, the Redeyef area in 1903, the Om El Araies area in 1904, and the Mdhila area in 1920, creating the Gafsa Mining Basin.

Phosphate mines contributed to building the Tunisian trade union movement and assisting the national movement and the armed resistance to colonialism. They played a leading role in providing the financial resources to build a post-independence Tunisia.

About 30,000 people work, directly and indirectly, in the various stages of phosphate exploitation, which means that this industry is the breadwinner for hundreds of thousands of Tunisians. It also brings large funds to the state treasury. However, this does not conceal the health, environmental, and social tolls of phosphate exploitation, which are terrifyingly high.

In addition to extracting crude phosphate in Gafsa and sending it abroad, chemical processing industries have emerged that produce agricultural fertilizers and phosphoric acid in Sfax. At the beginning of the 1960s - after the independence of Tunisia and the company’s nationalization - production progressed significantly, reaching 3 million tons annually. Then it increased to 4 million tons in the 1970s, 5 million tons in the 1980s, and 7 million tons in the 1990s, reaching 8 million tons at the start of the third millennium and maintaining its production capacity until 2010. In the two decades preceding the 2011 Tunisian revolution, phosphates contributed about 5 percent of the crude output and about 10 percent of the value of exports. Tunisia was among the top five global producers and exporters of this substance.

About 30,000 people work, directly and indirectly, in the various stages of phosphate exploitation, which means that this industry is the breadwinner for hundreds of thousands of Tunisians. It also brings large funds to the state treasury from profits and hard currency. All this does not conceal the health, environmental, and social tolls, which are terrifyingly high. The health toll not only concerns the large number of workers who died in the Damous mining tunnel, suffered serious accidents, or became chronically ill. It also threatens hundreds of thousands of Tunisians who live in areas adjacent to the phosphate extraction, washing, transporting, and transfer facilities in Gafsa, Gabes, and Sfax. These cities' residents suffer from a high prevalence of respiratory and skin diseases and high rates of various types of cancer compared with the rest of the country.

The environmental toll is multifaceted, as the phosphate industry depletes large amounts of water during washing, fertilization, and waste disposal. It is worth noting that most production and processing plants are in the southwest and southeast, which are the water-poorest areas in the country. Phosphate, its derivatives, factory fumes, and waste radiation seep into the air, land, water table, and the sea to create chronic and aggravating pollution.

The severity of the socio-economic toll varies from one area to another. For example, in the Gafsa Mining Basin, we can say without exaggeration that the Phosphate Company compensates for the absence of the state, as it is almost the only operator that is concerned with the issues of supplying electricity and drinking water. It also supports health and educational facilities, transportation companies, and cultural and sports activities. This continued until the beginning of the 1990s when the company adopted a restructuring plan that led to its merging with the Tunisian Chemical Group, which limited its independence, as well as reduced social expenditures in return for establishing a fund to support the mining areas and redirect economic activities there. The heaviest blow was the company's abandonment of the underground mines that require a large number of workers and its reliance on surface mines and sections that produce more quality and less expensive phosphate and rely on equipment and machinery more than people. The lack of job opportunities created widespread corruption when hiring. Bribery, loyalty to the ruling party, nepotism, and tribal affiliations are the standards for recruiting, rather than skills and competencies. All these factors created a state of increasing tensions that culminated in the outbreak of the uprising in the Gafsa Mining Basin in January 2008, which lasted for several months despite the repression and siege.

The concentration of phosphate industries in Gabes hit two key sectors: agriculture and tourism. The oases -- near which factories were erected -- could have been used for tourism. These oases overlooking the sea are unique; they were rich in pomegranate, henna, and apple plants. But pollution, unpleasant odors, and the distortion of the general appearance by factories and the commercial port all "killed" entire areas and deprived them of agriculture, sea fishing, and even the enjoyment of the sea and the beach. In Sfax, the air pollution in the areas surrounding the phosphate processing plants caused a drop in land prices, which attracted the poorer classes. As a result, residential communities, which are highly exposed to multiple pollution risks, were formed. Moreover, the infiltration of pollution into the air, the water table, and the sea greatly damaged the neighboring farming estates.

The phosphate sector has been suffering since the 2011 revolution. From 8 million tons annually in 2010, production fell to 2 million tons in 2011, and it has not recovered much since. The social movement, that has been going on for years, is the main reason for the decline in phosphate production.

Protesters have gone on strike at phosphate production and processing plants or blocked the passage of trains carrying crude phosphate. The protesters have two prime demands: allocating part of the revenues to develop the phosphate industrial areas and employing part of their unemployed citizens in the factories of the Phosphate Company and the chemical complex. Since there is no clear and practical conception of the issue of wealth distribution, the actual demand is employment. Thus, the factories of the Phosphate Company and the chemical complex, whose needs of workers and employees do not exceed a few thousand, find themselves required to employ tens of thousands of young people with or without qualifications.

The environmental and social bill may increase if the state does not restructure the sector according to a strategy that increases and diversifies production. More importantly, this strategy should give top priority to protecting the environment from mines, processing plants, and export seaports. It also has to reduce wastewater in laundries and allocate a big part of the profits to support real and sustainable development.

Fossil fuels: a black box?

This issue is perhaps the most ambiguous regarding Tunisia's natural resources. It often raises controversy about the reality of the available reserves. Many Tunisians believe that successive post-independence Tunisian Governments have hidden the real volume of oil and natural gas production. Some people's perception about the size of the country's energy resources is based on a simple logic. Tunisia lies right between two major fuel producers in the world, Algeria and Libya, so how can it not be rich? This argument does not take into account the desert area in Tunisia and the concentration of oil and gas fields in Algeria and Libya, which are hundreds of kilometers away from Tunisia.

El-Sissi and Resource Management in Egypt

27-03-2022

There is also considerable confusion, fueled by some Tunisian media, when it comes to this issue. The confusion caused by the oil and gas producing companies and petroleum service companies - which take care of transportation, maintenance, cleaning, and providing the needs of workers in the fields - has led some to believe that there are hundreds of oil companies in Tunisia. There is confusion about the difference between exploration licenses, exploitation licenses, and development licenses, not to mention the confusion between preliminary studies/estimated figures, real reserves, and the extent of oil extraction potential.

This does not mean that Tunisia does not have oil and gas resources. Tunisia ranks 48th in the world in oil, with a production of nearly 65,000 barrels per day (120,000 in the early 1980s), and 53rd in gas, producing more than 3 million cubic meters per day. The exploitation of oil and gas fields in Tunisia began in the 1960s. Most of it is concentrated in the desert areas and the southeast area of the Gulf of Gabes and is distributed between land and sea fields. The state-owned Entreprise Tunisienne d'Activités Pétrolières (ETAP) is in charge of the petroleum sector, while the Société Tunisienne de l'Electricité et du Gaz (STEG) is considered the first party concerned with the exploitation of natural gas for the production of electric power and heating.

Tunisia's reserves are estimated at 400 million barrels of oil and about 65 billion cubic meters of natural gas. Until the early 1980s, Tunisia was self-sufficient at the level of hydrocarbons, thanks to its production and the taxes it collects from the Algerian gas pipelines that cross Tunisia toward Italy. However, since the late 1990s, the energy shortage has gradually worsened. After the revolution, it reached what is estimated today at nearly 59 percent of the needs of the country. With the devaluation of the national currency and the constant increase in the country's imports of hydrocarbons, the bill became very exorbitant.

In addition to the obvious reasons such as the natural depletion of some fields and wells and the increase in the country's energy needs due to demographic growth and changing consumption patterns (cars, home electrical appliances, air conditioners, etc.), several other factors can help explain this shortage.

Tunisia was self-sufficient in hydrocarbons, thanks to its production and the taxes it collects from the Algerian gas pipelines that cross Tunisia toward Italy. However, since the late 1990s, the energy shortage has been gradually worsening. After the revolution, it reached what is estimated today at nearly 59 percent of the needs of the population.

Corruption is one of those factors. There had been exploration and exploitation licenses granted to specific companies, even though their offers were not the best. Perhaps the most prominent examples of this were the cases of the offshore ile Chergui field and the Skhira refinery (both in the central-eastern governorate of Sfax). Before the 2011 revolution, the right to exploit the ile Chergui field was granted to the British company Petrofac under suspicious circumstances. After the fall of late Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, it became clear that one of his sons-in-law had facilitated the company’s obtaining of the license after he received $2 billion in bribes from one of the company’s senior managers.

In 2007, Qatar won the project of building the Skhira refinery. However, the project was postponed due to political disagreements between the two countries because of Al-Jazeera Channel and because senior Tunisian officials demanded considerable bribes. There are also cases where corruption was accompanied by dereliction of duty. In 2018, the Tunisian Prime Minister dismissed the Minister of Energy and several senior officials after revealing that a petroleum company continued to enjoy exploration and exploitation concessions in the El Menzel field (off the coast of the central-eastern governorate of Monastir), despite the expiration of its license on 31 December 2009.

Corruption in this sector is not related to the volume of production, but rather to contracts and licenses for exploration and exploitation. Corruption is also present in the reports made by experts and consultants about estimates of the available reserves when exploring a field. This last fact is very important because the state relies on these reports to decide whether it will participate in the production expenses and share the proceeds with a private company, or leave the whole thing to the investors and just collect taxes.

The most serious problems lie in the policies of exploiting fossil fuel resources, which are characterized by ill management and the absence of clear strategies. At the beginning of its exploitation of oil and natural gas, the Tunisian state was adopting a policy of partnership with foreign companies to extract, refine, and market fossil fuels. This option was understandable given Tunisia's insufficient material and technical capabilities. But it was supposed, after two or three decades, to control the entire stages, from exploration to marketing. This is especially true after the state established several public institutions concerned with studies, transport, and refinery, and after it built generations of engineers and experts. But what happened was the opposite. Since the 1990s, the state has tended to leave the matter to foreign companies almost entirely. It also gave up part of its monopolized services to the private sector, especially in the logistical field.

Other than the natural depletion of some wells and the increasing consumption of energy, corruption is one of the factors explaining the energy shortage. There were exploration and exploitation licenses granted to certain companies, although their offers were not the best. For example, to make it easier for a British company to obtain a license, one of Ben Ali's sons-in-law took a $2 billion bribe.

If new oilfields and wells are not discovered and exploited, Tunisia's oil resources will be depleted before the middle of this century, and the energy shortage will become almost complete. So, what is the solution? Some suggest the exploitation of shale gas, aka schist gas. According to preliminary studies, there are two Tunisian areas rich in shale gas and shale oil: the first is in the southeastern governorate of Tataouine, and the second is in the central-western governorate of Kairouan. The exploitable reserve in both areas is estimated at 600 billion cubic meters. The country appears to be going down this path, despite the objection of many to the environmental and water costs of extracting this type of resource.

But the real solution is to rely more and more on alternative energies. They are renewable, cost less in the long run than traditional energy resources, and most importantly, they are environmental-friendly. Tunisia has great potential in solar energy (more than 3000 hours of sunshine per year and more than 100 square kilometers to install thermal energy storage systems) and, to a lesser extent, wind energy. The state seeks to raise the contribution of alternative energy in electricity production to 30% in 2030 instead of the current 3%. However, government policies in this field are still unclear, and procedures are slow.

In conclusion...

Tunisia also has iron, gypsum, marble, lead, zinc, cobalt, and other substances. However, their quantities are either limited or have not yet been exploited.

In most cases, the authorities do not manage resources optimally. Resources are drained, neglected, or given to foreigners for exploitation. Weak financial and technical capabilities may explain some of the failures, but other factors certainly exist. The most important of these are corruption, short-sightedness, and the absence of transparency, as well as the adoption of policies whose primary concern is to bring in hard currency and raise productivity, without much consideration for environmental-health aspects and social impacts.

Tunisia today finds itself facing great challenges, as it is threatened by thirst, desertification, and the almost complete depletion of its hydrocarbon reserves within two or three decades. But it is still manageable. The main problem lies in the political and economic-developmental choices of the country’s rulers. The dominant elites do not seem to have a clear and practical vision for prospective solutions. In fact, it seems that they lack an accurate understanding of the problem, and they have no vision whatsoever concerning the exploitation of natural resources - other than attracting foreign investment and finding markets to export the surplus. Even the opposition parties, forces, and trade unions rarely address this issue, and if they do, they usually chant slogans and clichés of political propaganda. Elites, the media, and even public opinion are preoccupied with "more important" issues such as "identity," "the civil state," and "equality in inheritance." Of course, everyone has the right to set their priorities. But they may be deprived of this intellectual “luxury” when drinking water and irrigation water is depleted, when they go thirsty and hungry, when they do not find enough resources to generate electric power, or when the air they breathe becomes saturated with polluting substances and diseases.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 14/06/2019