This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Mauritania’s underground, land, and seas treasure different kinds of natural resources. The country has minerals, like iron, copper, and gold, and enjoys its own share of petrol. It will soon see a gas boom, and has seashores rich with fisheries. Some of its terrain also boasts of extended and fertile lands. That, however, is not reflected in the people’s reality. According to the Mauritanian government, the poverty rate in Mauritania has reached 31 percent, while other statistics note 45 percent of the population, 75 percent of which is rural.

Not everyone can see the glitter of gold

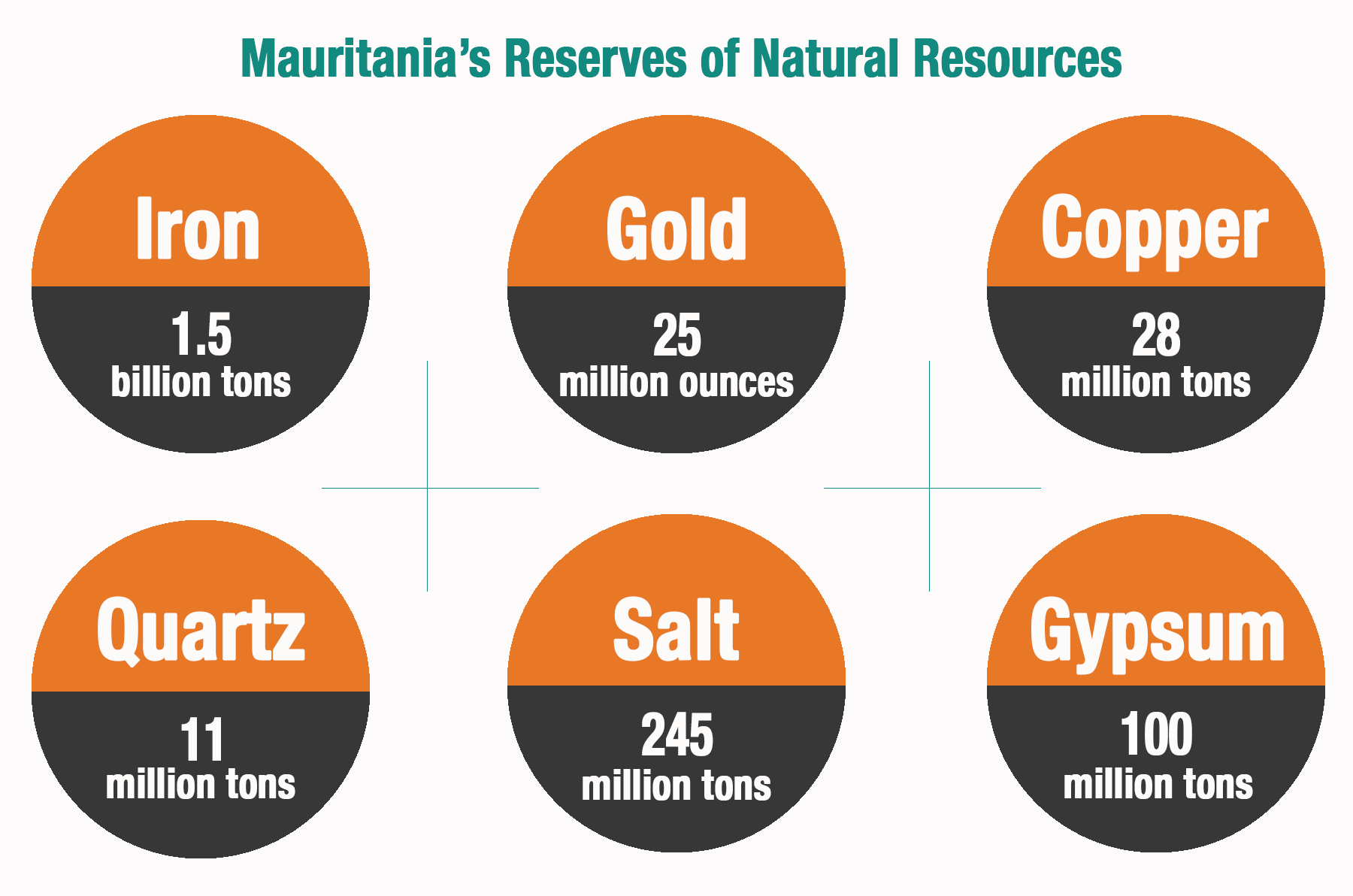

Mauritania’s iron reserves reach 1.5 billion tonnes. Its extraction began with French colonialism, with MIFERMA (1952), a partnership between French colonials and occidental merchants. Mauritania’s post-independence shares made up only 5 percent of this production, and the country has been exporting iron ore since 1963.

In 1974, Mokhtar Oueld Dadah, the first post-colonial president of Mauritania, would nationalise the company, following national struggles, and would become known as La Société nationale industrielle et minière (SNIM). Today, Mauritania holds 78 percent of the company’s shares, the Industrial Kuwaiti Bank holds 7 percent, along with other investors… In recent years, however, due to corruption, drained by offshore investments and the granting of private loans, the company has been in decline, and is now close to bankruptcy (1).

Mauritania’s gold reserve, which, like copper, hadn’t been truly used until 2008, amounts up to 25 million ounces, and its copper reserve amounts to 28 million tonnes. Mauritania is full of other minerals too, like quartz, of which it has a reserve of 11 million tonnes, and salt, of which it has a reserve of 245 million tonnes, whereas its gypsum reserve amounts up to 100 million tonnes (2).

More than 82 agents, both foreign and Mauritanian, invest in minerals. Furthermore, the opportunity to invest in traditional gold surface excavations opened to Mauritanian nationals in 2016, a domain that thousands of Mauritanians entered in the hope of enhancing their financial situation. This was, however, a trap for most of them, and a path towards suffering. Sidi Abdullah al-Bukhari (3), one of the people who tried out this domain, says: “Traditional excavators experience many forms of suffering. Many diseases have appeared among them, especially those related to malnutrition, as the food available in the area is terribly bad. When it comes to the climate, the area has strong winds and severe dust, which affects the excavation equipment and power generators. The area is also extremely hot in the summer and extremely cold in the winter.”

The Canadian Kinross company, which works through what is called the Kinross Tasiast Mauritania, is the biggest gold exploiter in Mauritania. It channels a mere 4 percent of its production to the government, in accordance with the distribution contract. This meagre percentage angers Mauritanians, who have launched many calls for revisiting the entire agreement, as the company is also accused of contaminating the environment.

Getting a traditional excavation permit costs five thousand ouguiya (the local currency, whereby one dollar equals 356 thousand ouguiyas) and requires a copy of one’s ID and personal picture. Sidi Abdullah says: “Some people have gone there in the hope of changing their reality, but lost their money, found no gold in return, and returned home disappointed.” Al-Bukhari sees that the “biggest winners are the tax collectors, the truck owners that drive people there, the stone-grinding machine owners, and the handymen like electricity generator technicians and tunnel diggers.” The path to reach the heart of Indoor (the field was inaugurated in 2018) in northern Mauritania is arduous. That field is the biggest of the areas open to surface excavation; the trucks drive excavators back and forth, as private cars are prohibited from going there.

Al-Bukhari shares his own experience of excavation: “Clandestine ways are inevitable if you want to sell the gold you excavate; the central bank pricing and calibration are unfair. The worst distress that could happen to an excavator is a medical emergency, as transporting patients is quite complicated.” That’s why there have been many death cases among the excavators, that is, in addition to being swept into the soil of the trenches that they dig…

There are 125 untraditional (industrial) excavation permits and 13 exploitation permits. Those include iron, gold, copper, quartz, and salt, with more than 15 thousand workers employed, half of whom do not work on a permanent basis.

The Canadian Kinross company, which works through what is called the Kinross Tasiast Mauritania, is the biggest gold exploiter in Mauritania. It channels a mere 4 percent of its production to the government, in accordance with the distribution contract. This meagre percentage angers Mauritanians, who have launched many calls for revisiting the entire agreement, as the company is also accused of contaminating the environment.

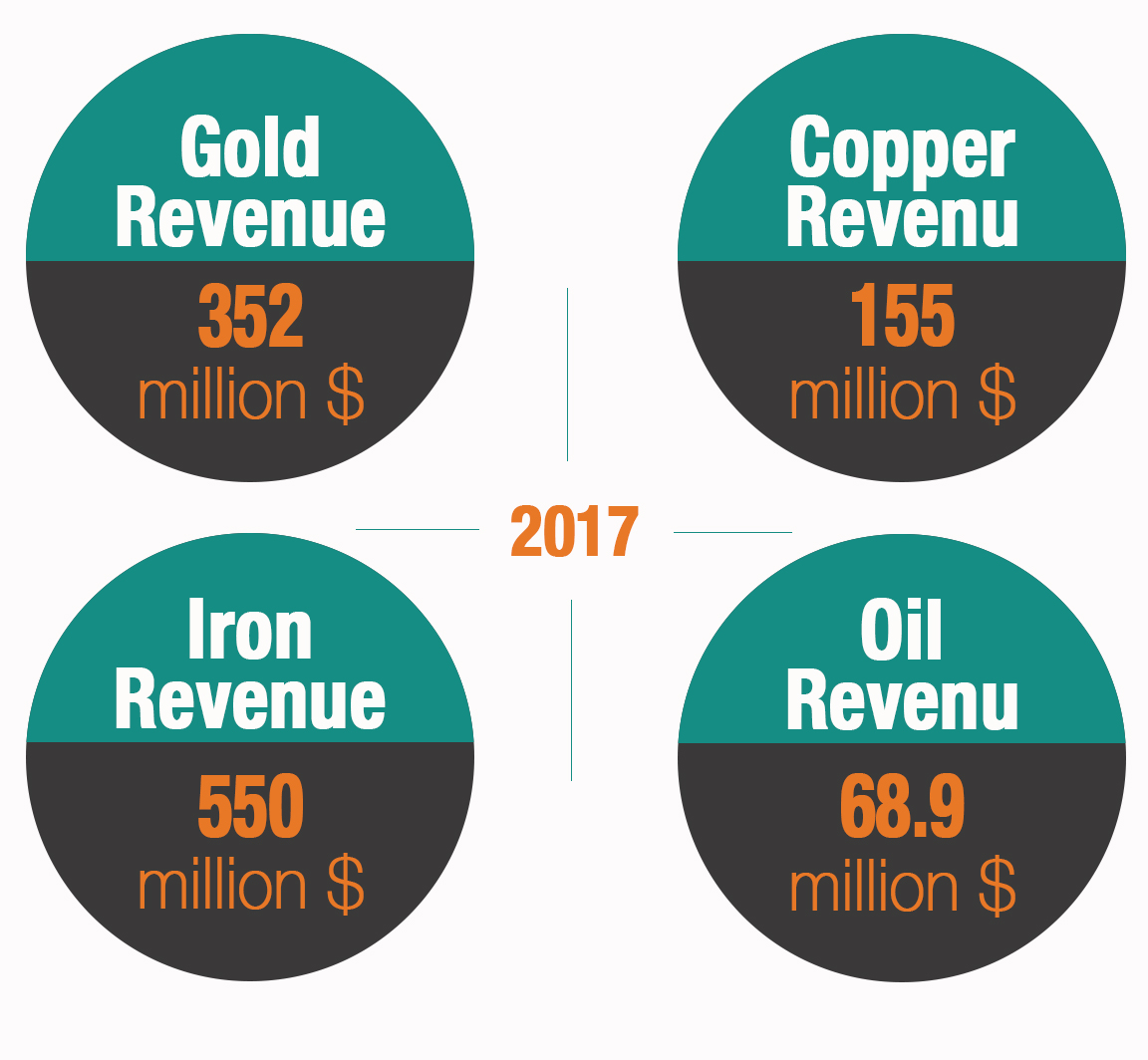

In 2017, the number of acquired gold resources has reached 352 million dollars (4), which amounts up to 100 million dollars increase compared to 2016, thanks to increased production (292,500 ounces as opposed to 229,000 ounces in 2016) due to extending the company’s excavation work and mine development.

El-Sissi and Resource Management in Egypt

27-03-2022

Moreover, in 2017, revenues accrued from copper reached 155 million dollars, while petrol revenue reached 68.9 million dollars. Exploitation of the Shanqeet field completely halted on the last day of 2017 as its productivity decreased. However, and despite that, the decision to shut it down was a shock to economic experts in Mauritania, and no explanations were given. The Malaysian company Petronas excavates petrol.

Mauritania has rich seashores

The Mauritanian seashores (spread along 755 km) are home to more than 300 types of fish, 170 of which are internationally marketable for their high quality. According to the Minister of Fishing and Maritime Economy (5), revenue from fish exports reached more than a billion US dollars, while the size of caught fishes reached 700 thousand tonnes. The minister confirmed that the fishing sector provided 60 thousand Mauritanians with jobs. Europeans top the list of beneficiaries of Mauritanian fishing, followed by the Japanese and the Chinese, while Mauritanians work with basic tools, without any governmental support.

Maritime resources have been over-drained by foreign fleets, which have no signed agreements with Mauritania to fish within limits. The agreements do not observe the environment, scooping up the seabed and harming traditional fisherpersons, who face dangers that bigger ships create, such as getting run over.

Maritime resources have been over-drained by foreign fleets, which have no signed agreements with Mauritania to fish within limits. The agreements do not observe the environment, scooping up the seabed and harming traditional fisherpersons, who face dangers that bigger ships create, such as getting run over. Mauritanian fisherpersons have been demanding the authorities to make development plans to help them and develop their sector as well as the local market, rather than take care of the international market only and foreign fleets, which have been left to squander the territorial waters unwatched. The fisheries represent a third of the country’s overall wealth.

Interest in Mauritanian seashores began with the Portuguese in 1432, through explorer Gil Eanes de Murara, followed by the Dutch and the French. The actual exploitation of wealth, however, only began in 1890, through a company in the Canary Islands, among which were multiple European countries.

The Paris Agreement, concluded between France and Spain in 1905, chronicles the beginning of French exploitation of Mauritanian maritime resources (6), where a French city was founded in northern Mauritania, Port Etienne, (now Nouadhibou), and then, in a short period of time, many French companies that work in the fishing sector showed up.

How are Mauritania’s resources managed?

Mauritania is a country with a small population (4 million people); hence, wondering about the way its resources are run is not only justifiable but crucial. In his study, Moussa Fall affirms (7): “Governance is being evaluated through the efficiency of exploiting resources in this or that country. As regards Mauritania, if we were to add up the different budget sectors and the revenue from hard currency between January 1st, 2009 and December 31st, 2017, we’d receive the following total: 3.514 billion ouguiyas of internal revenue and 28.535 billion dollars of foreign revenue. Having examined those numbers, the first question that comes to mind is this: Who would have imagined that the country had received these amounts of revenes at this moment in time? The second question would be: Where did all these resources go, considering the scanty results on the ground? If we were to exclude the efforts made to secure our external borders and some secondary facilities, the positive effect that one would expect from such resources is invisible in terms of citizens’ welfare and the country’s development in general.”

He adds: “The financial policies reflect the strategies applied in every country. In Mauritania, since 2009, the government has adopted financial policies that prioritise the following items: 1) Resources are rechannelled as investments (16 percent of the GDP), which are nonprofitable investments, 2) To pay back foreign debt, (5 percent of the GDP), at an elevated level due to over-indebtedness, and which dangerously reduces manoeuvring margins in terms of financing development, 3) Transfers and grants, to spend resources (3 percent of the GDP), and which inflated in the past years as tens of public institutes were created”. In his study, Fall affirms; ‘The attention that these three items have received has reduced the resources allocated to other domains, especially social sectors. Frequently, the country disregards the health sectors. These sectors, essentially consisting of education, health, national unity, and social cohesion have been pushed down to the bottom of our agenda”.

If we were to add up the different budget sectors and the revenues from hard currency between 2009 and 2017, we’d receive the following total: 3.514 billion ouguiyas of internal revenue and 28.535 billion dollars of foreign revenue. So, where did all these resources go, considering the scanty results on the ground?

Mauritanian financial expert (8), Mohammed Oueld el-Aabed, says: “From a theoretical aspect, natural resources in Mauritania are managed in accordance with their corresponding budgetary arrangements. The minerals as well as the fishing budgets, along with their relevant implementation documents, both include the guides and measures that would enable a transparent management of both these resources – that is, in an aim to guarantee their ideal contribution to the developmental process. Notably, in 2005, the Mauritanian state has adopted principles of the transparent extractivism initiative, which stipulates that all cash flows produced from mineral exploitation, including gold, petrol, and gas, must be declared. In 2013, a transparency initiative was adopted in the fishing sector.” Oueld al-Aabed continues: “Observers agree that transparency in both extractivism and fishing is still lacking, whereby permits are granted to exploit such resources beyond the determined courses of action. The state partners, especially the IMF and World Bank, have repeatedly alerted the Mauritanian authorities to the need for observing the legal texts so that the country is able to make use of its best natural resources […] Undoubtedly, failing to observe transparency in exploiting natural resources, especially gold and fisheries; the consequence is an immense injustice towards the state that doesn’t receive, in this case, the full financial rights resulting from granting excavation and exploitation permits thereafter. As soon as it stabilized following the 2008 coup, the current regime began limiting the issuing all production-division contracts in combustible materials to the executive branch, whereas the legislative branch would only approve them prior to their conclusion.”

So that gas has a better fate

Mauritania is about to experience a massive gas boom, whose exports would commence in 2021 and 2022, starting from the gas well in Tortue Ahmeyim – a shared field between Mauritania and Senegal, through the British Petroleum Company and Kosmos. The British Company estimates the reserves of that area to have more than 450 m2, as a new well, not too far from the capital, Nouakchott, has also been discovered, within Mauritania’s territorial waters. This field’s reserves have more than 60 trillion m2 of gas. It brought up much discussion on the importance of gas not having the same fate as its predecessors, of which Mauritania did not benefit.

Oueld el-Aabed says: “The country is about to experience a boom of exploiting important resources. Notably, until now, the Mauritanian government hasn’t provided the national public opinion with sufficient information about the subject. The Senegalese government, however, has assigned a few days of consultancy regarding the most ideal ways to benefit from the expected financial boom.”

Conclusion

The contradiction between the digital data available on the natural resources in Mauritania and the reality of the state and its people unveils the flawed management of its wealth. Changing this approach would necessitate adopting approaches based on transparency and committing to a management that reduces corruption opportunities. This, then, cannot happen in the shadow of a system accused of and involved in corruption, lacking in the management of its wealth and public affairs.

According to the 2018 Corruption Perception Index published by Transparency Global, corruption affects the management of the country – as it is ranks 144 out of 180 states, and has received 27 out of 100 points.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 27/06/2019

1) “Mismanagement and debts have weighed down on the Mauritanian economic giant, SNIM. An investigative report published in the Mauritanian Alakhbar newspaper in November 2018.

2) According to a statement that the Minister of Minerals made before the deputies of the national assembly on December 5th, 2016.

3) In an interview with the excavator conducted on April 2nd, 2019.

4) “The Lost Decade”, a study by Mauritanian economist Moussa Fall, published in instalments in the Mauritanian Al-Akhbar, starting July 30th, 2018.

5) A statement that the minister made for Rai Al-Youm in February 2019.

6) “Contribution to understand the reality of the fishing sector in Mauritania”, by researcher Al-Heiba Oueld Sid el-Kheir, published in Al-Qalam newspaper on February 5th, 2016.

7) Ibid.

8) In an interview held on April 3rd, 2019.