This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

“Who says the coronavirus doesn’t exist!” Salem (a pseudonym) is a man in his fifties; agitated, he curses himself and others when he remembers how, for months, he would insist to his family and friends that “There’s no coronavirus. It’s all lies”. That was before he caught the nasty disease, taking him away from his couch that evening, moving him from that municipal crane in which he works mornings, right into a hospital bed, where he suffered excruciating pain. He was also surprised to experience a sudden and unexpected fear, for life itself. It crept up from within the depths of his former denial, stimulating his certainty. Salem curses himself nonstop and seems completely convinced of every word he now utters: “You must take care!”, “It’s no harmless deal. No, not harmless at all, it’s tough!” (1) He reiterates as he breathes and sighs in relief, both literally and metaphorically, after finally recovering from illness. One feels that Salem is now as serious and dedicated to prevention as he previously was to disbelieving it, underestimating it, and reassuring his acquaintances with the likes of such thoughts.

At first sight, this man’s ambivalence may seem strange. Still, this is more than natural in a world where people often tend to doubt anything they do not fully understand or explain it by building on whatever prior information they had. In fact, this is what we all do, irrespective of our educational levels, scientific knowledge, socioeconomic background, or other such matters. We are fairly bound by our fear of the unfamiliar unknown, and must certainly be orbiting in the space of previous knowledge, cumulated throughout the years. As such, when addressing common myths about the coronavirus pandemic, its vaccines, or perhaps even conspiracy theories around it, all the way to underestimating it all together, this article does not reproach, mock, or judge any of these attitudes or opinions. Rather, it only attempts to revisit some patterns of such beliefs, in Lebanon in specific, and questions its causes and origins.

Although the widespread propagation of such beliefs and theories is potentially damaging to human health and life, understanding them, as a first step towards refuting them, is worthwhile. This is especially true in today’s world, as major events that presage radical changes to life on this planet abound, the extent of which we’re yet to comprehend, like climate change and pandemics.

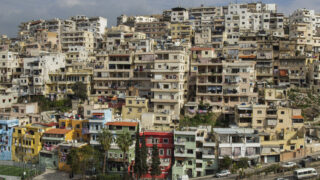

Coronavirus the “Lebanese”

Out on the street, there is talk about the explosion. (2) Other neighbours share their latest experiences with the prices of meat, vegetables, and essential items. One person asks about an indispensable medicine out of stock here, while another bursts angry at having queued since dawn, for hours, for gasoline at the station. A lady complains about the night-time power outages – and out goes sleep with them…Ever since late 2019 and until today, the more days go by in Lebanon, the more the number of topics that exhaust and burden the Lebanese grows. To question people’s concern over the latest coronavirus news, protection, and vaccination thus grows more uncomfortable by the day. It even seems a “luxury” the Lebanese do not have, although it absolutely concerns them. “Have you been vaccinated?”, “Which surgical masks do you use? FFP3, FFP2, or KN95/N95?” These seem questions exclusive to so-called First World citizens, as opposed to “Haven’t they turned on the power generator yet?” or “Where can I find this antibiotic? It’s out of stock!”, and other such questions.

According to the 2019 Ministry of Health statistics, 30 per cent of the Lebanese take tranquilisers regularly, another 30 per cent take them intermittently, while more than 40 per cent have suffered psychological strain at one point or another in their lives that required a treatment of tranquilisers or antidepressants.

The truth we must constantly repeat when speaking of the coronavirus in Lebanon is that the pandemic certainly hasn’t been the biggest of this little country’s worries in the past two years. Such a situation sets it apart from many countries around the world, where, for one year and a half, their primary concern has been the pandemic. Yet, it is shared in many other Arab countries that, like Lebanon, know what it’s like to have problems even bigger than a lethal global pandemic (as strange and scary as that may sound). Hence, it is understandable why some resorted to undermining the pandemic, either intentionally or unintentionally as part of an automatic reaction. To this one may add the question of mental health; in malfunctioning countries with stark incompetence that upsets productive and social roles, mental strain is quite perceptible. Lebanon is no exception to the rule: according to the statistics of the Ministry of Health in 2019 (3), 30 per cent of Lebanese take tranquilisers regularly, another 30 per cent take them intermittently, while more than 40 per cent have suffered psychological strain at one point or another in their lives that required a treatment of tranquilisers or antidepressants. Notably, these numbers leave out vulnerable groups like Palestinian or Syrian refugees and migrant workers, who are also prone to vast psychological and emotional stress. One must also note that these numbers refer to the period that preceded the beginning of the devastating economic “collapse”, which means it must only be worse now, especially with most pharmacies suffering interruption in medicinal supplies!

What “Precautions” in a Country like Yemen?

02-08-2021

This then is how bleak the picture has become, forming the daily life of citizens, residents, and refugees who, when asked about the coronavirus, can only answer that it has become the “least of their troubles”.

Conspiracy as a form of public opinion

Besides the trivialisation of a pandemic on account of other more urgent and direct life problems, one may note other instances of trivialisation, though premised elsewhere.

Those sometimes bluntly surfaced on social media, and particularly on Facebook, where one encounters a number of pages managed by Lebanese citizens and used to that effect. There’s not necessarily a vast number of them, but they’re there. And sometimes they’re influencers and make or break the opinions of their acquaintances and followers. By closely observing some of these pages, one notices recurrent patterns of a mocking or argumentative discourse, or both in the same breath. One of these pages wonders (4) why a “burning explosive super virus like Covid-19” needs such a ‘grand media campaign” to tell us, 24 hours a day, that it is a deadly fatal virus. The page mocks “the dramatic productions played out before the camera so spontaneously” and accuses ministries of health across the world of exaggerating the number of deaths. Finally, and most importantly, the page is armed with what it calls “given scientific facts” in order to contest science itself. For instance, the page has co-opted the very same #I_believe_in_science hashtag, which is rather normally used to encourage prevention or vaccination. In so doing, it virtually states that “It is because we believe in science that we refuse to believe what is being said about the gravity of Covid-19 and its outbreak”.

Proponents of such an idea often resort to foreigners who claim to be important doctors and share their opinions that dramatize the vaccines and intimidate people against it, giving false or unconfirmed information about the virus. They upload those videos with Arabic subtitles, which spread like wildfire on WhatsApp groups, and possibly circulate most among the older generations who use the application. It is almost certain that not one family group on WhatsApp has not had at least one of those cautionary videos that attempt to debunk medical information around the subject.

People’s disregard for protection from the virus doesn’t necessarily stem from denying its effect or their conviction in one of the conspiracy theories around it. Rather, it is often a mere fatalist decision, in resignation to God, nature, or luck – to each their own belief.

Such pages across Facebook often belong to individuals rather than groups. In some cases, one may detect a recurrent pattern of linking the pandemic with conspiracy theories, global freemasonry, for instance, Zionism, or even the devil himself. One of those individuals expresses what’s happening as “psychological warfare” to “control people’s minds and subjugate them to decisions that they wouldn’t accept in a normal situation”. Likewise, the staff and serpent on that WHO logo is said to be a reference to the story of Moses, Pharaoh, and his sorcerers (the sorcerers of the World Health Organisation, perhaps?). Some mockingly call the latter the Kahha (cough) Organisation, implying that it is it that spreads the virus in the first place… and other such theories that aren’t exclusive to the aforementioned page administrator (a Lebanese guy and college graduate, incidentally). Pandemic denial isn’t limited to older or uneducated people, then, but is rather common among individuals and groups all over the world.

In a number of industrialised countries, things reached the point of demonstrations in protest of the protective measures and in rejection of wearing masks.

Premised on some studies in political and social sciences (5), one may more comprehensively wonder about the origin of conspiracy theories. Those are present in most major events and mostly, rather constantly, accompany crises, pandemics, and sudden changes in public social and political life. This is precisely the case of Covid-19, the extent of its spread, and its effects. It would be understandable to dismiss such convictions as either the result of pathological symptoms (like paranoia), spread of misinformation, or what could be called broken knowledge – when considering how conspiracy theories are often prone to irrationality and illogic. As there is no scientific or precise method that could be used to look into each of these convictions, and as they are undoubtedly capable of circulating and spreading quite widely (not only in so-called third-world counties, but also in Europe, the United States, and a number of industrialised counties), the weight of questioning why people adopt and defend such theories could only fall upon those who wish to reason and pose that question.

J. Erik Oliver, a researcher in political sciences, asserts that conspiracy theories are simply just another type of political discourse that provides a framework through which public events could be explained. He considers conspiracies to be a mere form of public opinion and, therefore, subject to the same effects that determine traditional mass beliefs. Such narratives originate at contact points and in parallel with elite or prevalent discourses.

Pandemics, Politics, and Religion

Matters get further complicated when conspiracy theories intertwine with other factors that contribute to feeding fear and doubts among the Lebanese, like religion or politics. In one video, a priest is seen preaching to believers (6) that “The forces of evil have created the coronavirus by following the teachings of demons in hell… These are all followers of the Antichrist, like Bill Gates”. He then adds “We have a vaccine stronger than them all.

What is it? We take the Holy Communion after confessing to our sins. We paint our foreheads, chests, and hands with holy oil. We drink sanctified water”. He then concludes, “They make people live in fear and terror so that they wouldn’t leave their homes, so that they wouldn’t pray”. On the other hand, on that Facebook page that promoted conspiracy theories, Quranic verses like “Rushing forth, heads masked” (7) is used in reference to those “servile” people who wear masks to protect themselves from the virus. All the while, the verse is decontextualised, stripped of its original setting that describes the horrors of judgement day and resurrection. Those clerics deeply impact their congregations and religious folk who look up them as men with authority. In parallel, some clerics did use their platforms to encourage people to protect and vaccinate themselves.

In the meantime, there’s politicians and their influence. In December 2020, in one of the news pieces in Aljumhuriya Newspaper, it was said that the president of the Lebanese Republic, Michel Aoun, wouldn’t take the vaccine and would simply continue to apply preventive measures in Baabda Palace in order to protect himself from the virus. Still, in February 2021, only two months following such statements, Aoun finally took the vaccine. As a political leader and president of a republic, the influence of such news on public opinion (among the Lebanese in general and Aounists in specific) cannot be taken lightly. Similarly, during an interview broadcast in December 2020, when asked whether he would get the coronavirus vaccine, Hassan Nasrallah answered that he would rather wait than get the US-made Pfizer vaccine once in Lebanon. Such a statement instigated an all-out controversy on social media, specifically among Hezbollah supporters, on vaccines in general and Pfizer vaccines in specific. Although vaccination campaigns had already started in a number of different countries, including the United States, the aforementioned statement reignited conspiracy theories to the effect that Americans rather wanted to “test their vaccines on peoples of the region before they did theirs”.

One of the coronavirus-denying pages is managed by a Lebanese, who took it upon himself to scold the “resistance crowds” in Lebanon for their disregard to Ali Khamenei, supreme leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, who proclaimed “distrust in American and British vaccines”. The page held receiving vaccines like AstraZeneca and others against these followers, and, in many of their posts, even attacked Minister of Health Hamad Hassan, counted among Hezbollah governmental appointees. One of those posts considered that he had better avoid importing those Western vaccines than be “enslaved to the World Health Organisation and western countries”.

The Minister of Health “holds his sword” against the coronavirus

The Lebanese Minister of Health himself constituted a rather strange phenomenon in handling the coronavirus pandemic in Lebanon, with its own implications on the population. The Lebanese remember the minister’s tweets during the first wave of the pandemic in the country, with his infamous words of “no need to panic”, which many considered a form of medically baseless reassurance. Right after, a wave of overwhelming infections broke out and completely exhausted the health sector. Once the first wave was curbed, the minister responded to one of the tweets that wondered whether “a second wave coming?” with much confidence and certainty: “it wouldn’t dare!”. Such a strange answer, which, once more, formed yet another reassurance based in neither scientific facts, studies, or serious data, came as self-praise to himself and the minister’s capacity of warding off any new coronary waves… as if it were that simple. Such lightness of being resurfaced time and again in the minister’s positions. Once, cameras captured him brandishing his sword in proclamation of his victory over the coronavirus in Baalbek, carried atop shoulders (in June 2020, that is, much before the second, and tougher, wave hit). Television channels caught him cutting through a large cake in celebration, amidst citizens who decided to symbolically celebrate Hassan Nasrallah’s birthday, and despite lockdown orders. The minister’s management of the crisis was objectionable, and calls were made for his dismissal, even from within his own party. His confusing and incomprehensible statements caused resentment among both opponents and supporters.

Even when he gave up his positive attitude, trying to comfort the doctors of Lebanon in their ordeal, for the loss of their colleagues who passed away from Covid-19, the minister’s vocabulary didn’t help. He wrote a peculiar sentence: “The tidings of comfort have run out, the pathways have narrowed down in a spiral of oppression, a classic example of the moaning of poverty and gloating of fate, brushing against the verge of a blackness we fear. We have been afflicted with mist before our sound judgement – an anger hitting all manner of life and modesty. The untainted white received its share of slander, despite all the praise and eulogies. Doctors of Lebanon, forgive us.” The tweet provoked mockery and sarcasm among its readers, with its incomprehensible wording and exaggerated sensationalism – a trope equally present in the minister’s other tweets.

One may say that the role the minister of health played in the past two years has lacked the seriousness and gravity required to manage a crisis of this dimension. It also contributed to creating false impressions about the simplicity of overcoming the crisis, or prematurely implied that it has been overcome.

Artists fluctuate and affect public opinion

People’s disregard for protection from the virus doesn’t necessarily stem from denying its effect or their conviction in one of the conspiracy theories around it. Rather, it is often a mere decision that stems from some fatalism or resigning their fate to God, nature, or luck – to each their own belief. Blind faith in maktoub (the foreordained) is prevalent in a religious Lebanese society, though with various degrees of religiosity. Following death or a coronavirus infection, sentences like “he has been struck” are often heard, inspired by the tenet of “Say ‘Never will we be struck except by what Allah has decreed for us’” (8). Once more, this is characteristic of the peoples of the region and the way they have handled the pandemic. For example, in Egypt, during an interview at El Gouna Film Festival, which kept its 2020 edition amidst the peak of the second coronavirus wave, actor Yasmine Sabri’s following comment created a buzz in social media. In response to a reporter’s question on how worried she was about the coronavirus, she said: “Whoever catches it catches it, whoever continues continues, and survival is of the fittest”. Even if not religious, such lightness reflects a cross-communal approach to a weighty matter over which humans have no direct control. Here, one may note the positions of a few artists, singers, and actors who influence Lebanese and Arab public opinion. These, too, have contributed their own share of misinformation and fearmongering, but also sometimes urged people to take the necessary precautions.

Doubt, panic, falsified facts, and rumours are the characteristics of crises. The Lebanese have been encountering all these when asking for their money at the bank, their wages that barely equal a hundred dollars by now, or when trying to make up their minds about the coronavirus.

For instance, Lebanese singer Ragheb Alama was one of the most prominent people to have changed their mind before public opinion. “I fear this vaccine. The coronavirus itself is a conspiracy, and the vaccine is an even dirtier conspiracy… an international political conspiracy”. (9) Thus proclaimed Alama in a television interview with Al-Jadeed Channel, insisting that anytime he sat around a group of people, he would ask “Would you take the vaccine?” only to affirm that the answers were in the negative “at a one hundred per cent rate.” According to his own statistics! However, Alama himself declared, a few weeks following his first statement: “I’m waiting for the arrival of the vaccine into Lebanon and will be the first to take it”. Lebanese singer Haifa Wehbe, with 7.5 million Instagram followers, addressed her followers through an InstaStory: “40 years have gone by and no preventive treatment against cancer or AIDS has been discovered; they’ll need at least 100 more years to do so; even the common cold has no treatment. As for the coronavirus, its vaccine has been discovered in less than a year, and they expect me to take it. Thank you, but no thank you. I won’t take it”. Haifa Wehbe confuses bacterial and nonbacterial diseases, and distrusts the vaccine without having the necessary facts, just like many of us foreign to the medical domain do. The difference, however, between any of our acquaintances who repeat such thoughts and Haifa Wehbe is that she has millions of people for a public – a public who could indeed be impacted by a public persona’s opinion who enjoys such popularity.

One may clearly notice, however, that after one year of living with the virus and upon entering 2021, and with the beginning of the vaccination campaigns around the world, Lebanese, Arab, and international artists have become much more careful about giving any negative statements about the vaccines or questioning the coronavirus. To the contrary, a race between those influencers, artists, and politicians has been ongoing for vaccination. They’ve been publishing their pictures as they get the vaccine and encourage people to do so as well. Notably, however, these celebrities do not have to wait in line or register through official platforms like the rest of the people; a considerable number of them went to the United Arab Emirates to receive the vaccine with their families quite early, way before their turn came in Lebanon. They then published pictures and videos on their pages and thanked the United Arab Emirates for their hospitality. (10)

Conclusion

Lebanon has been under the yoke of a number of simultaneous burdens. It suffers unrest and economic, living, political, and sanitary anxiety. Lack of things “certain”, solid, and final in the country throughout these past two years has been an inextricable feature of all life dimensions, way beyond the coronavirus pandemic. Doubt, panic, falsified facts, and rumours are the characteristics of crises. The Lebanese have been encountering all such phenomena when asking for their money at the bank, their wages that barely equal a hundred dollars by now, or when trying to make up their minds about the coronavirus.

Were we to zoom out and look at the world at large, we couldn’t but link this entire human and universal experience with our fragility as humans, individuals, and different communities, but also as one universal community that lives on the same planet and has suddenly ended up forced to come face to face with its fragility. It has been forced to reflect on its relationships, politics, philosophies, human-to-human relations but also human-to-nature relations, and in such an unforeseen and urgent matter that cannot afford any delay. Faced with the initial fear and ignorance of what, how, and why things happen, it is only natural for ideas to explode and for doubt and worry to prevail. One positive thing remains in Lebanon’s case, however – and despite its negligibility – manifest in the waning waves of antivaxxers and the noticeable increase (11) in vaccination turnout.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 18/07/2021

1)Testimony of a Lebanese on his experience of the coronavirus. “Salem” is a pseudonym.

2) Beirut’s port explosion, August 4th, 2020, which reaped the lives of more than 200 people and injured 6,000.

3) Ministry of Health statistics in a report titled “Mental Health and Substance Abuse” (2019).

4) A personal page run by an individual.

5) J. Eric Oliver and Thomas J. Wood. “Conspiracy Theories and Paranoid Style(s) of Mass Opinion”, American Journal of Political Science 58 (4): 952-966.

6) Link to video: https://twitter.com/i/status/1327289193995907079

7) Surat Ibrahim 43.

8) Surat At-Tawbah 51: “Say, ‘Never will we be struck except by what Allah has decreed for us; He is our protector.’ And upon Allah let the believers rely.”

9) A BBC Arabic report on Ragheb Alama changing his mind on the coronavirus and vaccines: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=POyeArzLmvQ

10) In the United Arab Emirates, it has been trending in recent months to grant Lebanese and Syrian artists (like Najwa Karam and Assi El Hellani from Lebanon, all the way to the grand actor Yasser al-Azma from Syria, for instance) wholesale golden residencies that allow them long-term residency in the UAE, where they enjoy numerous privileges like vaccination and others.

11) According to an extensive survey carried out by the Arab Barometer, 65 per cent of the Lebanese comprised in the statistics said that they would likely or very likely get the Covid-19 vaccine as soon as it became available, which renders Lebanon as one of the Arab counties with the highest rates of openness and turnout to the vaccination, following Morocco and Libya.