Amal cannot forget the face in the picture on the wall where she used to work. A woman in her thirties, she is the mother of several children and the wife of a man she has not seen in years. They were separated when the Sudanese regime arrested both due to their tribal affiliation, she says. Despite her pregnancy, prison officers beat and abused her. Tears choke Amal’s words as she remembers the painful events, and she does not want to tell more. she was released two weeks later. Whereas She knows nothing of her husband’s fate. Since then.

After her release, she made the decision to take her children to Egypt. She first stayed in the flat of a friend living with her husband and children in Cairo. “They didn’t put up with us for long, me and my children and a new baby on the way… They threw us out after one week.”

Refugees who arrive in Cairo tend to move into low-income neighbourhoods like Faisal, Ard el-Lewa and El-Hay El-Asher in the Nasr City district, which offer cheap accommodation. These are areas where the citizens complain about the prevalence of baltagiya – criminal gangs –, theft and harassment, especially from tuk-tuk drivers, and the insecurity of the streets at night. The suffering of African refugees is compounded by racist harassment against them and their children in the street.

Amal found shelter and support for a while with another friend who lived alone with her daughter. She then found a job as a domestic worker.

This was not the first house Amal ever worked in, and it would not be the last. She usually spends limited periods with one employer and then finds work somewhere else, with periods of unemployment in between. But what occurred in this house, she cannot forget.

The family that employed her consisted of the lady of the house – ‘Madam’ – and her son, daughter and husband, the man in the picture on the wall. When Madam travelled, Amal continued to take care of household duties. But one day the man took advantage of his wife’s absence and raped Amal.

Dr Jaidaa Mekky, Assistant Professor of Psychological and Neurological Diseases at the University of Alexandria, explains that sexual violence is a power-based crime; the perpetrator is motivated by the display of his power more than by pleasure. He is therefore usually older, bigger and more influential than his victim.

Hurt and frightened, Amal left the house and never returned. She did not tell anyone about what had happened, saying, “The man threatened me with his status. He said if I go and complain, he will know… I remained silent… I’m scared.” After the rape, she suffered from insomnia. “I couldn’t sleep because of this man’s threat.” It took her weeks to overcome the first shock.

A victim of rape can be afflicted by a “severe nervous shock”, Dr Jaidaa points out, which may come in addition to physical harm that requires medical attention, such as a fracture or wound. The duration of this post-traumatic stress varies from case to case, as do the symptoms, which may include anxiety, panic attacks, phobia, increased heart rate, visual and sleep disorders, nightmares and daytime flashbacks to the incident.

Amal has not had the luxury of rest and recovery. She had no choice but to find another job to to feed her children, beside the “insufficient” aid she receives from a refugee organisation. Although she is skilled in handicrafts and able to carry out administrative tasks, there is not enough money to be made from such work to even cover the rent. She therefore sought another position as domestic worker.

According to her account, Amal reveals that this rape incident was not her only experience with sexual assault. During a summer month, she found a day job at a villa with a wage of 300 Egyptian pounds. When the woman left “to run some errands and said she would not be back late”, she did not keep her word and left Amal alone with the fifty-year-old man. “I have developed a phobia of being left alone with the men,” Amal says.

The man sat down in his underwear and asked Amal to massage him. “When I refused, he threatened to fire me, so I left.” She was also denied her wages for a whole day’s work. She only had 12 pounds in her wallet. She walked from the villa to get to the main road.

“The streets there are quiet. It was about 4pm.” Suddenly three young men blocked her way. “They dragged me into an abandoned house, beat me and raped me… The three raped me… I tried to scream, but they twisted my arms and gagged me… And there was no one there to help me.”

In tears, Amal points at her arms, where the effects of the assault, and She still felt pain in her wrist, which had been sprained. She also had been hit in the upper thighs, and the next day of the incident, "my whole body was swollen."

Amal knows the three men had been sent by the man from the villa, as they reproached her for “not listening to what you’re told” and threatened to accuse her of theft if she went to the police. “I was, of course, scared.”

With that, the picture of the first man who threatened her is back on her mind.

696 Rape Cases in One Year

Amal is one of numerous African women who have come to Egypt as refugees and find themselves often defenceless targets of sexual violence, as perpetrators feel they will not be held accountable for their actions. According to a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Cairo report, Egypt Response Plan for Refugees and Asylum-Seekers from Sub-Saharan Africa, Iraq, and Yemen 2019, 1,231 cases of sexual and gender-based violence were reported to the UNHCR and its partner CARE International, by Africans and other nationalities (Iraqi and Yemeni) in 2018. They make up 81 percent of the total number of reported cases for that year. Of those 1,231 cases, 696 were rapes, 239 were sexual assaults, 155 were physical assaults, 109 were psychological/emotional abuse, and 28 were forced marriages.(1)

Important questions the report does not answer, however, are: Do these statistics include incidents in the host country, as well as those occurring on the transitional journey and in countries of origin? How are these crimes linked to racism? And are the perpetrators from the host or the refugee country?

Numerous other UNHCR reports, studies and media reports (2) show that assaults on refugees are certainly not limited to Egypt.

Africans form the second largest refugee community in Egypt after Syrians, who make up half of all refugees in the country. At the end of 2018, refugees from four African countries – in order: Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea and South Sudan – accounted for 36 percent of the refugee population, according to the UNHCR statistics. The latest statistics (September 2020) indicate that this has risen to over 40 percent (In a different order of countries: Sudan / South Sudan / Eritrea / Ethiopia, and this does not include other African nationalities such as Somalis ...), while Iraqis and Yemenis together make up about 6 percent . (3)

Amal is not the only one in her family who has come in contact with violence. Her adolescent daughter was on her way home from school when a group of young men followed her and tried to force her into their car. She was lucky to be rescued by a passer-by who heard her screams. This incident left her not only with deep cuts on her hand, but also with psychological scars that show in her growing refusal to go to school or leave the house at all. She still experiences episodes of panic, and suddenly starts screaming.

Amal and her daughter received psychological treatment at a specialized organization. But the mother believes that "there is no improvement”.

Dr Jaidaa points to the greater impact that sexual violence has on the psyche of refugees due to their displacement, particularly when they differ from the host population in language, religion or appearance and are subject to discrimination, especially women. They are more likely to become depressed and to feel helpless or powerless in the absence of a Psychological safety net made up of family and friends. The younger the victim, the more severe the effects of sexual violence.

According to 2018 UNHCR statistics, 267 out of 1,231 cases involved minors (217 girls and 50 boys); 13 of these children were separated and 80 were unaccompanied (which means the majority of cases concern children that live with their families). Of the 267 crimes against minors, 107 were rapes, 97 were sexual assaults, 33 were cases of psychological abuse, 25 were forced marriages, and 5 involved physical assault. The report notes that all cases have “been identified and consequently counselled by the SGBV [Sexual and Gender Based Violence] unit”.

85 Rape Cases in One Month

During the first ten months of 2019, the number of reported cases of sexual and gender-based violence reached 1,312 cases, 90% of them were of African nationalities. “In the month of October 2019 alone, UNHCR, in liaison with CARE International, responded to 142 SGBV cases, out of which 89.4 per cent affected women and girls, and 10.6 per cent affected men and boys. Rape remains the highest reported offense of all SGBV incidents. In October 2019, a total of 85 incidents of rape were reported, constituting 60.7 per cent of the total SGBV incidents reported in the month..”, according to the report: "Egypt Response Plan for Refugees and Asylum-Seekers From Sub-Saharan Africa, Iraq & Yemen, 2020".

When Amal was raped the first time, she did not know of the UNHCR reporting mechanism. She describes her helplessness: “I didn’t understand much, and I was scared because he threatened me… I didn’t know what to do.” However, she did report the second rape and the assault on her daughter to UNHCR. They received her reports without further investigation or communication with the police to arrest the perpetrators, Amal says. They focus solely on providing psychosocial support to victims.

Amal does not know anyone in her surroundings who has gone through what she has. It is not a topic anyone really talks about, she says. “It is embarrassing for me to talk about it… I feel ashamed.” Therefore, she has not opened up to many people about her assault, apart from refugee organisation workers and one friend.

Harsh economic conditions

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic last March ushered in tough economic times for Egypt, which have affected Amal’s life as well. The woman who last employed her had to let her go and she failed for months in finding a new work. Her psychotherapy sessions became take place over the phone, which she finds neither comfortable nor useful.

UNHCR financial aid also stopped last December(2019), for no obvious reason, which has happened before and requires her to submit a new application and wait for months until it kicks back in. This makes her feel humiliated, she admits.

Amal is four months behind on her rent (1,250 pounds per month) and her landlord has begun to press her to pay, if only in part, as he is losing patience. She relies on food aid from the Catholic Church to feed her kids. “Sugar, angel hair pasta… and sometimes they put a chicken in the bag.” But the same products arrive month after month, driving her children to despair. “Pasta and rice every day… They don’t eat, they just cry.”...” I have no money to buy them anything”.

Sometimes she does not even have enough money for transport and must go the long way from home to the refugee aid association by foot to ask for help, only to return disappointed. “Really, is this not death?”

According to the UNHCR website (published in February 2019), “80 percent of refugees in Egypt live under miserable humanitarian conditions and cannot even meet their most basic needs.” UNHCR states that due to a severe lack of funding, it is limited in its ability to assist refugees, which has become even more difficult during the current Covid-19 crisis. The need for support has increased among refugees working in the informal sector, as many have been laid off and unemployed since the beginning of the crisis . (4)

In general, a low economic standard, limited learning opportunities, especially in higher education and lack of language proficiency render the situation of refugees – in any country – very fragile and leave them perceived as outsiders or defenceless targets, vulnerable to exploitation, sexual violence and other dangers. Refugees often dare not report what happens to them. According to the UNHCR report mentioned above, many refugees and asylum seekers from sub-Saharan African countries in Egypt do not speak Arabic or English and are at risk of isolation, face social and economic challenges, and strongly depend on others for their daily interactions and fulfilment of basic needs.

According to 2018 UNHCR statistics, about 48 percent of non-Syrian refugees registered with UNHCR have no education or primary education only, and about 46 percent have completed secondary school or higher education. The report further mentions that “refugee professionals and those with advanced levels of education face further difficulties to be accommodated in the Egyptian labour market” and that getting work in general is a challenge for African refugees, most of whom are subject to exploitation and discrimination. Thousands of African refugee women are employed in the domestic work sector, where some suffer from verbal and physical assault.

Many are forced to share an apartment with other refugees to reduce their cost of living (a UNHCR rental survey from 2018, using a random sampling of refugees and asylum seekers, showed that 60 percent of African, Iraqi and Yemeni respondents lived in separate rooms in shared apartments). However, overcrowded flats increase the possibility of sexual assault.

Amal describes her mental state as unstable, saying she has become to treat her children nervously. The night before we met, she said she did not sleep. She takes antidepressants, a suicide desire comes to her mind by throwing herself out of the window, or putting her hand into a coverless fan, without realizing. She also takes medicine for shortness of breath and suffers from pain in her heart. “I am mentally and physically exhausted… from all of it, all of it,”

Amal’s most important concern at the moment is to find a job for her children’s sake, even if that means bearing abuse until the work is done and she can take her wage. “I don’t have another solution. I will continue the therapy and work for my children… I will endure anything if only my children are safe.”

Dr Jaidaa argues that a victim’s desire to take legal action against the perpetrator is a healthy sign, reflecting that she feels she still exists and has rights. The absence of this desire may be a bad sign, perhaps indicating seeing oneself not as a human being, but as a mere machine that must complete work and turn in order for life to continue. If the effects of rape develop into depression or pathological anxiety, then medication or even admission to a mental health facility is required, because victims may be at risk of hurting themselves or committing suicide, overwhelmed by guilt and depression.

Amal does not want to return to Sudan, for fear of persecution; nor does she want to stay in Egypt. When I ask her about the possibility of marrying again after such a long separation from her husband, she replies with a rhetorical question: “Marry again and have more children?!”

Then she adds: “I honestly still love my husband and hope he comes back. Not enough years have gone by for me to give up on him. I hope one day I will hear his voice again saying, I’m here!”

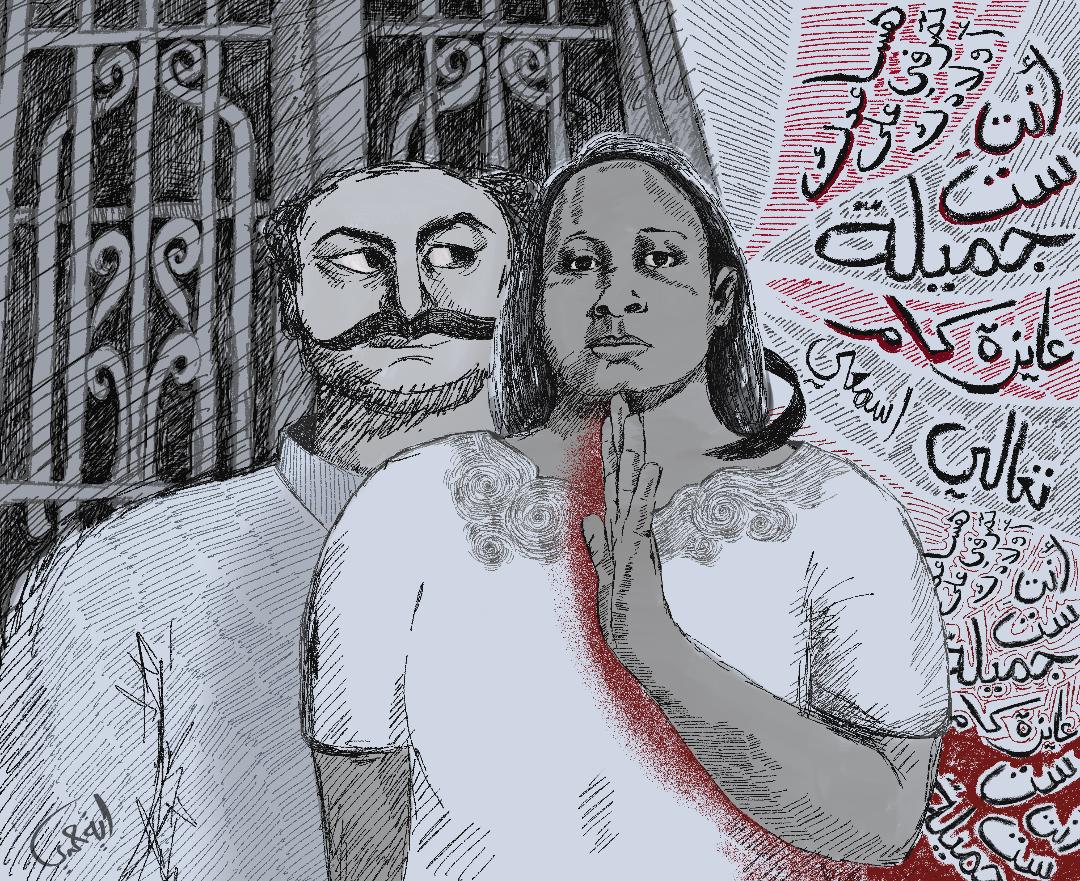

Illustration video of Amal's story

Social Pressures and Reporting Difficulties

As those who work within the competent organizations to assist refugees who fall victim to sexual violence point out, female refugees are often looked upon as “left to their own devices”, as if the law does not protect them the way it protects citizens. They are perceived as defenceless targets and are therefore vulnerable to assault. And although domestic work, where women face potential perpetrators behind closed doors, puts them at greater risk, assault also takes place on the street, in the victim’s own home – for example, when a plumber or electrician comes to fix things – or in the war-torn country of origin. There are cases where the perpetrator is from the refugee community himself.

Male African and Syrian victims are exploited based on their need for shelter, money or work. In the case of children, the perpetrator is most often a person from within their circle of acquaintances or colleagues (children may work as vendors or in mechanics workshop, for example). Refugee aid organisations provide psychological and legal assistance or, if relocation is required, support them with a one-month payment of rent and insurance. The first service they offer victims of rape is a medical examination and treatment to prevent infections and pregnancy, which requires quick reporting. Victims who arrive at a later stage of their pregnancy need to carry the baby to term.

These specialists see that the problem is more complicated than offering immediate solutions to it, and it is hard to control or prevent it entirely. But refugee women can be made aware of the dangers of going out and using transport on their own and late at night and advised to try and stay clear of such situations, this can help reduce their exposure to these accidents. And some victims refrain from reporting the crimes against them, to avoid blame, suspicion and the request for evidence, this is equally the case for refugee and Egyptian women.

Quick reporting is not only required to receive the necessary medical procedures, but also for criminal proof through the effects that the aggressor leaves on the victim's body and clothes, as Intissar Assaied, a lawyer and the general director of Cairo Foundation for Development and Law, says.

According to Article 267 of the Egyptian Penal Code, which applies to anyone who commits a crime within the country, the penalty for rape is the death or Imprisonment for 25 years, after the toughening of the penalties for a number of sexual assault crimes in 2011. Law articles concerned to these crimes continue to be criticized, particularly by women's organizations. A research paper by Nazra Foundation for Feminist Studies, entitled "Sexual Violence between the Philosophy of Law and Implementation Problems" (published on the Foundation's website on May 30, 2018) indicates that there are deficiencies in these articles at the level of concepts and definitions, in addition to problems in implementation, which include: the difficulty of proof and the absence of evidence witnesses, victims may be subjected to temporary detention at the police station after the accused report a vexatious counter-complaint, and the length of the litigation procedures.

Dr Jaidaa says the reporting procedure can increase stress for a victim, since police officers and the judiciary tend to be men who may implicitly accuse the reporting woman of encouraging the crime or being the root of the problem, intensifying her sense of shame. Societal pressure on the victim, sending the message that her death would be best for everyone, can lead to suicide.

Both refugee and citizen women, then, face these difficulties in the legal reporting process, and suffer from the pressures of a society that assigns responsibility for the crime to the victim, searching for fault in her behaviour towards men rather than condemning the perpetrator, bearing in mind that the refugee status is more fragile

The issue of sexual assaults has been for months, and still is a matter of widespread discussion in Egypt, starting in the digital space. Here, women have found platforms to raise their voices freely, to share their stories as survivors of sexual violence and to name their alleged assailants, among them sons of influential people, after years of silence for fear of stigma, reputational damage and threats. This has spurred government, parliament, the judiciary, religious institutions and union activists to move and engage with the issue.

Amidst all this, however, the voices of refugee women have remained absent and of no interest.

Single Women

It is notable that the overwhelming majority of refugee women who have been victims of harassment and rape considered in this investigation (sharing their stories directly or indirectly through other refugees and activists) are single family providers. They lost their husbands to war or arrest in the country of origin, were separated from them in the host country, or came to Egypt unaccompanied. A South Sudanese woman activist says that while there are cases of married women being targeted, the absence of a husband requires a woman to work and engage with more people, increasing the likelihood of exposure to abusers.

In a society that regards single women as weak with no men to defend them, they find themselves more vulnerable to pressure and harassment due to their surroundings, and frequently become objects of greed and suspicion.

Christine from South Sudan, a University of Juba graduate who is now a domestic worker, was stalked by a man from her area whom she did not know. He always waited in front of her building, harassed her and spoke to her in obscene terms. The man, in his forties, wanted to pay her for a relationship. One evening, he suddenly knocked on her apartment door. Although she had locked the door from the inside as usual, she was so scared that she locked herself and the baby in another room until he left. With the help of an organisation she was able to move to a new apartment, as she no longer felt safe in the old one, thinking the man could go further than knocking next time... This is what happened with another refugee, referred to by the activist, who had been raped after her apartment was broken into, before leaving Egypt for Europe.

How much do you want? Come, listen

The consequences of abuse reach far beyond the moment a perpetrator approaches his victim. His actions can poison a woman’s life and damage her dignity and reputation. If the perpetrator stems from her immediate environment, a neighbour or the guard of her building, and she rejects him and threatens to report him, he may start to stir up gossip about her; he may accuse her of receiving men in her flat, making her the object of suspicion and disdain among the people around her. This causes great pain and humiliation.

Children of Rape

The impact of sexual violence may not be limited to a woman‘s mental and physical suffering; it can be life-changing in other ways, such as in the case of pregnancy from rape. While there seem to be no statistics on the number of children born from rape in Egypt in general, or the refugee community in particular, there are living examples that leave no doubt about the psychological, social and legal complexity of the relationship between mother and child, both victims of rape.

Intisar is a refugee from Sudan and a single mother. In order to provide for her children and pay for their education, she accepted work at a private house as carer for an elderly woman. However, horrific crimes awaited her instead. Several men held her hostage in the house for days, beating and raping her.

“They attacked me and knocked me unconscious, hit me so hard on the head that I lost consciousness,” she says. She did not want to remember the details of the “tragedy” after waking up. “I found myself stripped naked… “

As Intisar’s refugee card had expired, the police refused to take her statement. She was also turned away by UNHCR and its partner organisation on the basis that she had to renew her card. Weeks later, she realised she was pregnant. She went to an abortion clinic, but could not complete the procedure because of the side effects of the medication.

She was six months pregnant when she found another organisation that supported her despite the expired documents, requiring only a passport, and there she received psychological counselling. The birth of her child was excruciating due to an internal injury sustained from a previous rape in a Sudanese prison while pregnant, which had caused a miscarriage. After giving birth, questions about the fate of the child arose.

“I had no choice but to keep him,” Intisar recalls. She had to accept a seemingly inescapable fact. With the help of a lawyer appointed by UNHCR, she obtained a birth certificate for the child.

Mohammed Farhat, a lawyer at the Egyptian Foundation for Refugee Rights (EFRR) in Cairo, points to several obstacles that refugee women face in registering children born from rape, even though their rights are legally protected. Obtaining a report on the rape from the competent officer is the first challenge. Sometimes this report is not issued because the victim did not report the crime; other times, the police refuse to issue it.

The matter becomes even more complicated when the assault took place during the refugee’s journey to the host country or in the country of origin. Hospital staff may be unwilling to handle the birth certificate for a child born from rape or an illegal relationship, or an employee may not accept a refugee card as proof of identity, unaware of the special status of refugees. Sometimes an employee refuses to serve the mother and her child due to social prejudice. Farhat adds that the failure to register children turns them into stateless persons.

Intisar is asked about her relationship with the baby. After some silence, she replies, “This is a sore spot with me… It really is a big problem… and I don’t know how to solve it.”

She says the child is physical proof of the crime committed, and the perpetrators continue to threaten her. Can she live in constant fear? Is it better to put the baby in a shelter? Or to be taken by a rich family? ... all of these and other are questions on her mind...“I am truly in hell, in hell, in hell, and I don’t know how to get out of it.” She has not yet filed a paternity lawsuit, fearing damage to the reputation of her family and the future of her son, who “has no guilt”.

Intisar is aware that that she has not fully recovered from her trauma. Her therapist urges her to express her sadness and to cry, but she cannot cry any longer as it gives her headaches. She has lost her sense of taste and has developed a fear of closed places, including even the supermarket.

Despite “one shock after the other”, Intisar laughs and says, “The worst misfortune is the one that makes you laugh”...”I know one thing at the moment… Feelings are completely out of my accounts.. I live life as a duty… because I am responsible for people, without me, they will be lost.”

Intisar’s financial struggles are worsening. The little money she receives from an aid organisation has been reduced to the equivalent of $75 a month. The payment is also usually late, “which means our life is in constant limbo”. From this money, she needs to pay for rent, water and electricity, food, drink and baby supplies. She recently received a message on her mobile from the World Food Programme informing her of the temporary suspension of the care allowance for pregnant and breastfeeding women. The only nappy brand she can afford to buy gives the baby a rash.

From time to time, she has to send her children to earn money at a workshop, long hours for a small wage. During the pandemic, her children have switched to remote learning and the Internet package has become an additional financial burden. For a long time their meals have been reduced to dry bread. Intisar says she has gone twenty days without a single pound in the house, with bills for water, electricity and the rent piling up. “We could find ourselves evicted and on the street any moment.”

A while ago, Intisar thought about doing a project and submitted it to a refugee association, but they denied to fund her on grounds of having received financial support years ago for a project she could not complete it. She concludes the interview by saying that life of refugees in Egypt is very difficult and opportunities in front of them are few. Economic pressures make them vulnerable to exploitation, such as in her case, since everything that has happened to her was because of her financial needs.

This is still the case, only more weight has been added to her shoulders.

*****

-The stories in this investigation are but a few of the many tragedies kept secret by refugees in Egypt.

-The identity of all interviewees has been hidden, by request.

-Paintings: Aya Hamdy

-Illustration video of Amal's story : Mona Ali Allam (Script and Voice Over) and Aya Hamdy (Illustration and Direction).

*****

Translated from Arabic

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 13/10/2020

1- The link of the report in English (pdf) on the UNHCR site, https://www.unhcr.org/eg/wp-content/uploads/sites/36/2019/05/EgyptResponsePlan2019EN-1.pdf

2-See for example a documentary on sexual assault where the victim was a Syrian child in Germany and the perpetrator was a German man who works for the Red Cross

Another documentary addresses sexual assault against Syrian adolescent refugees in Greece

3- Fact Sheet from UNHCR, Egypt, September 2020, via this link https://www.unhcr.org/eg/wp-content/uploads/sites/36/2020/10/UNHCR-Egypt_Fact-Sheet_September-2020.pdf

4- Official response from UNHCR via e-mail, While the response did not include answers to my questions about sexual violence against refugees in Egypt.

This investigation was conducted with the support of Candid Foundation.