This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The complex structure of Yemeni society has made it challenging to analyze. The challenge is made more difficult due to the complications that have accompanied the political and social transformations - the most recent of which is the ongoing war in Yemen since 2015. On the other hand, Yemeni society suffers from poor historiography and systematic social documentation, if any at all. The chronic political turmoil has led Yemenis to focus their attention on managing their lives, away from looking into the reasons behind the disruptions of social relationships or finding the potential ways to regulate these relations.

In addition, the successive political authorities ruling Yemen have consistently classified society as homogeneous, based on the predominant religion (Islam) and the predominant language (Arabic). The classification is not without an authoritarian arbitrariness in the way it deals with the realities of this society, as it aimed to deny the rights of some minority groups, even though their members are Muslims who speak not only Arabic but also the common local dialects. Among these groups are the marginalized people, Muhamasheen, who have been known as “Al-Akhdam” (the servants) in Yemeni society. They are not the only group whose marginalization is partly based on color. Al-Ahjur is a nother group with distinct African features; however, they live a nomadic life in rural and desert areas and rarely have a passion for city life.

Although the tribal tradition in Yemen has helped sort out a social hierarchy based on descent, profession, and property, it has greatly contributed to pushing the Muhamasheen to the very bottom of the social heap.

Where did the Muhamasheen come from?

Some historical sources suggest that the Muhamasheen in Yemen had likely came into existence as a group in the aftermath of the ancient wars between Yemen and Abyssinia. However, there is substantial historical evidence suggesting the key role of migration in their influx into Yemen. The importance of these references to migration lies in the fact that African migrants continue to flock to Yemen to this day from the sea and practice activities similar to the ones taken up by the Muhamasheen. As migration patterns changed and evolved over the ages, it is possible to differentiate between the migration conditions before identity papers and passport control systems. In addition, the coastal cities of Yemen were not far from the waves of the slave trade. However, the history of the Muhamasheen in Yemen did not record cases of official slavery as much as it recorded comprehensive and unfair social discrimination against migrants’ human rights..

Although the tribal tradition in Yemen has helped sort out a social hierarchy based on descent, profession, and property, it has greatly contributed to pushing the Muhamasheen to the very bottom of the social heap in the country.

In the face of this discrimination, which is close to exclusion, the Muhamasheen identified themselves with a stereotypical character reinforced by the tribal society with its various customs and traditions all over the country. But it is clear that one word has been particularly hurtful to the group for generations: "servant." To them, the word is so offensive that they have accepted to be dubbed “Muhamasheen” (marginalized ones) as a lesser-of-evils alternative. They resisted enslavement by delving into the labyrinth of “social alienation”: a way of life that might fit James Scott's description of everyday resistance through non-compliance. Their work as garbage collectors and sanitation workers, with their lack of concern for personal hygiene or access to sanitation services, lack of religiosity, and openness to sexual relations between men and women, are examples of their resistance through non-compliance.

The Muhamasheen in Yemeni cities

The Muhamasheen constitute 12 percent of the total population of Yemen, according to the last population census in 2004. This statistic was confirmed by Numan al-Hudhayfi (1), chairman of the National Union of the Muhamasheen in Yemen. Although they are found all over the country, they are concentrated in the central and southern areas, close to the coasts of the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea: Aden, Lahij, Abyan, Al-Hudaydah, Taizz, and Ibb.

The Muhamasheen resisted enslavement in ways that might fit James Scott's description of everyday resistance through non-compliance. Their work as garbage collectors and sanitation workers, with their lack of concern for personal hygiene or access to sanitation services, lack of religiosity, and sexual openness, are examples of their resistance through non-compliance.

After the September 1962 revolution in the north, internal migration developed, and the Muhamasheen were part of this development. However, their presence in an urban environment has not been accompanied by increased awareness of civil rights, although the article on equal citizenship in the first constitution of the republic stipulated that “Yemenis are equal before the law without discrimination based on gender, origin, language, religion, or sect.”

The situation was different in the south. After the October 1963 revolution, and specifically after the British evacuation in 1967, the socialist regime sought, practically, to integrate them into society. Nevertheless, the neighborhood of Dar Saad, north of the city of Aden, was labelled as the largest informal settlement of the Muhamasheen.

Except for Aden, a British protectorate, the Yemeni cities before the revolutions of September 1962 and October 1963 did not witness an orderly urban expansion outside their old walls. However, the 1970s made a difference. The empty land spaces on which the present-day cities are built outside the ancient walls are crowded with migrants from the countryside or other cities, including the Muhamasheen.

The Yemeni unification between the northern and southern parts in 1990 constituted another turning point in the path of internal migration, and the Muhamasheen were not far from this transformation either. However, their lives at the bottom of the heap continued in parallel with the increasing spread of rural values and tribal customs within the cities. The civic values that were growing slowly, especially in the north, were stifled by the gradual weakening of the power of the Yemeni unification state. Since the accelerating collapse of the state reached its climax with the outbreak of the recent war, civic values have become as weak as a dying man’s last breath.

Foothold

In light of this situation, the Muhamasheen lived in search of a foothold in the cities. The greater the number of streets, the greater their influx into the city as street sweepers, sanitation workers, and shoemakers, specifically shoe tailors. They are jobs that people of tribal origins resented, even if they come from poor families. As their numbers increased in the cities, the Muhamasheen built their huts on the outskirts, forming random gatherings called Mahawi [singular Mahwa, a term typically used to describe a dog shelter].

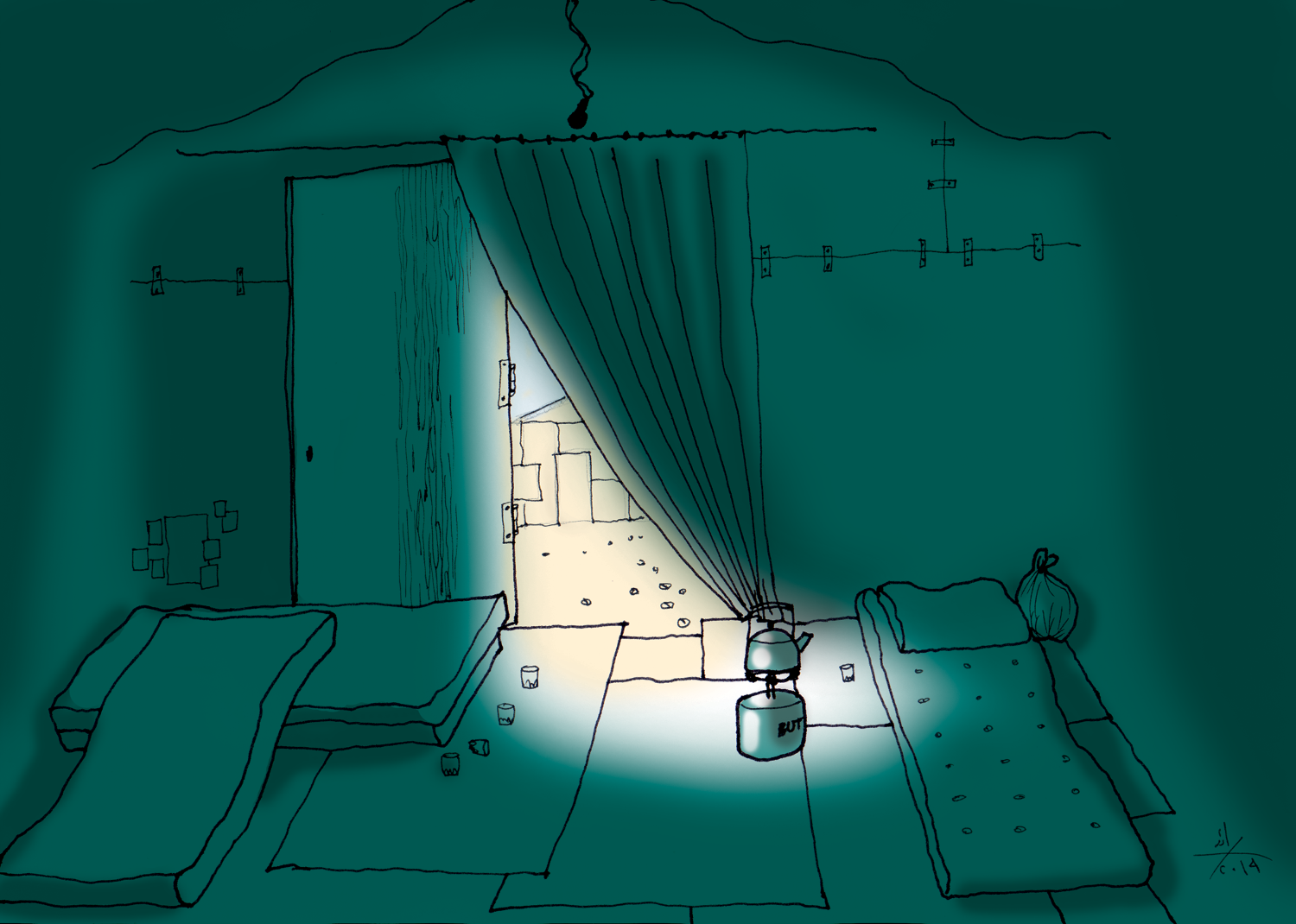

The Mahwa consists of dozens and sometimes hundreds of huts. The hut ("Dima" in Yemeni dialect) is often built of cardboard, zinc sheets, and small pieces of wood. Its area does not exceed 6 to 9 square meters, and it usually does not include attached or outside toilets. In places, where they stay for a long time with no imminent threat of huts being removed by state authorities or landowners, the Muhamasheen might build their huts with small stones and mud, rarely with concrete bricks. But even then, Mahwa is not immune from the threat of demolition; it might even be set on fire if its inhabitants resist.

The Muhamasheen slums in Taizz

According to the population census of 2004, the population of Taizz Governorate is 12.16% of the total population of the Republic of Yemen, with an annual growth rate of 2.47% (2). With this percentage, the governorate is the largest in terms of population and population density as well. The proportion of the city's population relative to the population of the main cities in the country is 11.9% (3).

At least ten slum areas inhabited by the Muhamasheen are in the city of Taizz and its nearby suburbs. Some of them are located in the middle of residential neighborhoods: Mahwa Al-Rawdah behind Al-Thawrah Hospital, Mahwa De Luxe within the areas of the city center, and Mahwa Al-Hasab between the city center and its western margin. There are several Mahawi, which are relatively far from the crowded neighborhoods but are within the city fringe areas: Wadi Jadid, Wadi al-Masal, Al-Mufattish, Bir Basha, and Kalabah. There are also Mahawi in the suburbs near the city: Al-Hawban, Mafraq Mawiyah, and Al-Dabab.

As the numbers of the Muhamasheen increased in the cities, they built their huts on the outskirts, forming random slum areas called Mahawi, which consist of dozens and sometimes hundreds of huts. The hut ("Dima" in Yemeni dialect) is often built of cardboard, zinc sheets, and small pieces of wood.

The Mahwa is a gateway to another realm: late-night Khat-munching sessions, songs played on double loudspeakers, hybrid dances in which Yemeni and African folklore mingle indiscernibly. Before cassette tapes, the Muhamasheen used to participate with the Dawashin in holding wedding concerts in the countryside of Taizz. When the Muhamasheen moved to the city, they took their passion for art, music, and dance with them as if it were their safe haven in the face of the tyranny of discrimination.

From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, the Usayfirah area, north of the city, was associated, in the popular imagination, with the slum dwellings of the Muhamasheen and sewage collection basins. Because the city planning, implemented in 1978, included directing sewage water to Usayfirah, urbanization remained undesirable toward it. But when the empty spaces on the other sides of the city diminished, streets and buildings were constructed in the area. Then the Muhamasheen were forced to look for other places in which to settle, including steep areas overlooking the torrential rain streams.

At the beginning of the third millennium, the government established two residential cities for the Muhamasheen in Taizz, with the support of the European Union and the World Bank, respectively: Al-Amal City in the eastern end of the Suq al-Jumlah-Kalabah area (96 housing units); and Al-Wafa City in the western end of Al-Bararah (240 housing units). It built the latter within the project to protect the city of Taizz from flood disasters. Each housing unit contains at least two rooms, a kitchen, and a bathroom. The residential city was built with concrete bricks and a contiguous horizontal shape to form a square/rectangular neighborhood as a whole, open on one side.

Given the Mahawi population, this housing initiative is a drop in the bucket. There is no official statistic available for the number of the Muhamasheen.

However, compared with the number of their communities and the 12% that Al-Hudhayfi said he obtained (exceptionally) from the National Center for Statistics, these units will not be able to accommodate a third of the Muhamasheen in the city, even if the government distributed each housing unit to two families or three. Thus, the Mahawi remained the most efficient accommodator for the population explosion of the Muhamasheen, with early marriage, unregulated births, reluctance to education, and almost non-existent health care. In addition, some families could not adapt to the lifestyle inside the new housing settlements. Some beneficiaries ceded the ownership of their housing units to other families in exchange for money.

In this context, we must first clarify some terms. The broad social classification divides society into tribal people and servants, or Muhamasheen per the modern definition. Regarding the class/caste based structures, there is a kind of competition over the top social position between the Sayyids (the Hashemites) and the tribes that have the power and ownership. Below them, the caste divisions vary according to occupation: merchants, craftsmen, workers, etc. The groups considered most socially inferior on the grounds of the profession are butchers, barbers, and sometimes restaurant and café workers, who are just “Maqhawi” (café people). In the central areas, there is also another socially inferior group called Al-Dawashin (plural of Dushan, panegyrists who come to give praise to certain people on specific social occasions or events). But this particular phenomenon has been fading in the recent years. In the tribal areas of the north, there is a group that calls itself the “Abna’ al-Khums.” It consists of workers who serve the tribal elders and landowners, singers, musicians, and the craftsmen who take up the crafts traditionally practiced by Yemeni Jews. Ironically, Al-Dawashin and the Abna’ al-Khums are “white”. Although tribal customs have undergone some changes due to the development of society, tribalism can be noticed in some cases. It is especially true because of the tribal leaders’ control over the legislative institution after the September Revolution in the north and the unity between the two parts of Yemen. Although slavery has vanished, families with a history of slavery still have their members -- who are also white -- stigmatized as descendants of slaves. That is why tribes forbid marrying into these groups.

A closed society on the margin

Like in other cities, the Muhamasheen in Taizz form a closed community in the face of the tribal community. Although they go out most of the day to work, and sometimes to beg - especially women and children - they do not welcome the entry of the tribal people into their private space, the Mahwa. Inside this space, a different realm unravels: late-night Khat-munching sessions, songs played on double loudspeakers, hybrid dances in which Yemeni and African folklore mingle indiscernibly, and songs brought by early migrants from their villages. Before the cassettes, the Muhamasheen used to participate with the Al-Dawashin in holding wedding concerts in the countryside of Taizz, with songs, chants, and hybrid dances to the rhythm of drums and flutes. When the Muhamasheen moved to the city, they took their passion for art, music, and dance. They continued to practice them within their closed community as if they were their last safe haven in the face of the tyranny of discrimination. These traditions are similar to those of the Gypsies in other countries in the region. (Gypsies are called Nawar in the Levant and Kawliya in Iraq.) In his book “Kings of Arabia,” Ameen Rihani compared the job of the Dawshan in Yemen to the job of Al-Mshowbish in Lebanon. It is said that Abnaa al-Khums in northern Yemen and Dawashin in central Yemen are of Persian or Turkish origin. Tribes used their services after capturing them in wars. One of them was a popular poet named Ghazal al-Maqdisiyah, who fought against discrimination in the nineteenth century. A famous verse of hers says: “Equal, equal, O servants of God, we are all equal…No one is born as a son of a free woman; no one is born as a son of a slave.”

A single government initiative was launched to enroll the Muhamasheen students in universities without requiring them to fulfill all conditions and by adopting a scholarship system of free education. However, due to the government's lack of interest in improving the labor market to keep pace with the university graduates of the Muhamasheen, most graduates could not find a job anywhere but in the “Cleanliness and City Improvement Fund”; a job they could have obtained without getting an education.

However, there is one exception in which this closed society opens up to the outside. That happens when a member of the tribal community wishes to integrate into the Muhamasheen society. Ironically, the Muhamasheen slums in Taizz have received individual cases of people coming from the tribal community to join them. Although we can count them on one hand, these individuals were motivated by parental persecution and discrimination against them as tribes’ children. On the other hand, there are increasing individual attempts by people from the Muhamasheen community to get closer to the tribal society, despite their awareness of the difficulty of integrating into it. Such an integration begins with education and taking up religious commitments. For the Muhamasheen individual, this means a drastic change in lifestyle and living on the borderline between the “center” of the large society they are entering and the “margin” of their own community. In this way, teachers, civil servants, civic activists, and poets have emerged from the Muhamasheen community.

Although the mutual integration attempts are seen as an indication of the weakness of the tribal structures in Taizz, they cannot be considered an indication that the social status of the Muhamasheen differs from that of their peers in the rest of the Yemeni governorates. The city known as the "Capital of Yemeni Culture" is still far from forging a better relationship with the Muhamasheen who live there. Those who qualify as "organic intellectuals" of the city dwellers face marginalization within the larger society. At best, they can profess their sympathy for the Muhamasheen and their issues; they can mingle with activists who have exited or are trying to break out of the Mahwa lifestyle. Interpersonal relationships often arise out of a shared position of marginalization, but without daring to take the relationship any further.

The tribal community has its misconceptions about the Muhamasheen “who do not bury their dead.” In fact, the Muhamasheen are invisible, alive or dead! If they quarrel with tribes, it always ends up in a reconciliation, even in murder cases. The only difference is that the tribal people have the right to refuse a settlement and demand retribution or revenge.

In practical terms, the nature of the Mahawi dwellings, the difference in social customs, and the absence of political advocacy for the right of the Muhamasheen to integrate stand as the most prominent obstacles to the development of this relationship. Perhaps this is what the representative of the Muhamasheen in the National Dialogue Conference (4) , Numan al-Hudhayfi, meant when he said that the conference members showed him an "ostensible or obligatory respect." However, this “obligation” comes from a desire to avoid accusations of racism; it has nothing to do with compliance with any law criminalizing discrimination based on color or origin.

The Muhamasheen’s tragedy is that they cannot act as equal citizens without being directly insulted with that slur: servant. Moreover, the tribal people do not attend the weddings and funerals of the Muhamasheen, even though marriage contracts are drawn up between the communities by the marriage official who is necessarily a tribal person. In the event of death, many individuals are deprived of a proper religious burial ceremony. Thus, mystery shrouds the deaths and burials of the Muhamasheen community. Instead of caring and sharing, the tribal community weaves baseless misconceptions about the Muhamasheen “who do not bury their dead.” In fact, they are a community of invisible people, alive or dead! If they quarrel with tribes, it always ends up in a reconciliation, even in murder cases. Although reconciliations in murder cases are at the heart of tribal custom, the difference is that the tribesmen have the right to refuse a settlement and demand retribution or revenge. In cases of disputes, the Muhamasheen rarely resort to the police stations because the problems are usually minor and can be settled by the wise men of the Mahwa. In large residential gatherings, the local authorities may appoint a wise man from the Muhamasheen; however, this does not give him the upper hand.

A sole literacy initiative

In the mid-2000s, several voices of Muhamasheen activists began to emerge. Following the mounting international criticism of the miserable situation of this group, the government adopted an initiative to enable the Muhamasheen students with low averages at school to get a university education.

The government set up the initiative in the universities of Taizz and Sanaa. The two universities received these students within the parallel education system, and the government exempted them from all tuition fees as part of this system. Although the initiative was a candle in the dark, it was not without administrative corruption and attempts to exploit the opportunity given to this group to break the state of reluctance to learn. The initiative continued to motivate the children of the Muhamasheen to go to school and university.

However, the illiteracy rate is still high, and reluctance to learn has been linked to their fear of integrating into a society that still demeans them in an offensive manner. However, due to the government's lack of interest in improving the labor market to keep pace with the university graduates of the Muhamasheen, most graduates could not find a job anywhere but in the “Cleanliness and City Improvement Fund”; a job they could have obtained without getting an education, with a daily wage system or a contract, and only recently, with fixed government salaries.

Between two regimes and war

The social barrier remains the most formidable barrier to integrating the Muhamasheen into public life. The beginning of the third millennium was a turning point for the Muhamasheen because the international community was keen to improve their housing and educational conditions and to enable them to join civil service without discrimination. This interest, accompanied by international pressure on the government, led to the emergence of the voices of civil activists among the Muhamasheen, who completed their education and developed their cultural skills by self-effort. President Saleh’s regime allowed these voices to emerge, attracting some to practice civil and human rights activities under the umbrella of the ruling party, the General People's Congress (GPC). Accordingly, the GPC’s base had more members of the Muhamasheen than any other party, including the Socialist Party, which took the lead in integrating the Muhamasheen into society and state institutions during its rule in the south.

The representative of the Muhamasheen in the National Dialogue Conference described the attitude of the other conference members towards him as "ostensible or obligatory respect." However, this “obligation” to be respectful here comes from a desire to avoid accusations of racism; it has nothing to do with compliance with any law criminalizing discrimination based on color or origin.

In Taizz, the votes of the Muhamasheen went to the ruling party candidates. Due to the Muhamasheen’s abstention from the polls and reluctance to engage in many aspects of the life of the larger community, the ruling party formed field committees in each electoral district in the country to encourage individuals to register their names in the voter lists or to transport them on the election day to cast their votes. They were often supervised by people who knew the community and could influence voters.

Because relations within the Muhamasheen community are characterized by the predominance of individualism at the expense of collective cohesion, the ruling party used to form payment committees for the Muhamasheen of Taizz under the supervision of the CCIF management, their employer. If some voters demanded money, the supervisors of the payment committees could give them the allowance of the one election day. However, this is not limited to the Muhamasheen only.

Like census statistics, there are no official statistics available on the numbers of the Muhamasheen voters at the level of each electoral district. However, al-Hudhayfi (5) confirmed that former President Ali Abdullah Saleh promised him that he would support his candidacy for Parliament in the name of the GPC in District 34, one of the city's five electoral districts. This district includes some eastern neighborhoods and part of the northeastern neighborhoods, including the Suq al Jumlah-Kalabah, where the Muhamasheen’s residential city of Al-Amal is located.

This election did not take place in 2009 as was planned. Thus, it was not possible to have any results that could have indicated the rise of the first MP from the Muhamasheen. However, President Hadi, who succeeded Saleh following the protests of the February 2011 revolution, issued a decree to form the National Dialogue Conference panels. They included al-Hudhayfi's name, not as a representative of the Muhamasheen, but in a special list called the President's List.

Ten months after the conference, the final version of the dialogue document included 11 points as constitutional and legal guidelines to address the situation of the Muhamasheen. All the points have recognized their right to equal citizenship in all aspects of social and political life, including enabling them to hold public and senior positions and to join security and military institutions without discrimination. But before that document came into effect, the five-year-old war broke out.

Invisible Slums: “Al-Ghaba” in Tunisia’s Sfax

01-06-2022

The Slums of Algeria: Invisibility and Hope

18-05-2022

In April 2015, during the first month of the war, a residential neighborhood of the Muhamasheen in the eastern suburb of Taizz was bombed by the Arab coalition aircrafts, killing and wounding more than 25 people. It was not the only raid that left victims among the Muhamasheen, but it was the first. As a result, many young people of the Muhamasheen joined the ranks of the Huthi group as fighters or security conscripts. Within the areas of the city under the control of the legitimate government, the Al-Bararah neighborhood was the scene of violent confrontations between the two sides. During those confrontations, the residential city of Al-Wafaa was shelled by the Huthis several times, one of which resulted in the death and injury of more than six people. On the other hand, dozens of the Muhamasheen joined the war fighting in the ranks of the “legitimate government” forces at the time as well.

The dilemma of integration

Upon close examination, the split within the Muhamasheen over supporting one of the two sides of the war appears to be a division that exists in parallel to that present in the larger Yemeni society, and not as part of it. The split within the larger society was defined by a conflict of political and factional interests. Also, the tribal and regional identities that transcend national consensus have constituted a haven - and a springboard at the same time - for those who chose one side of the warring parties. On the other hand, the Muhamasheen had no interests of the sort. Their right to obtain identification papers and their participation in elections did not pave the way to their social empowerment and equal citizenship, as the discrimination faced by this group remains primarily social.

If the relations among other components of society are so unhealthy that they cause political instability, what degree of response can a society in this situation show to integrate the Muhamasheen into it or even recognize their particularity as a minority?

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 03/10/2019

1- A private interview with the author for the purpose of this study.

2- National Information Center, last viewed on 29 August 2019.

3- The second report of the final results of the general population and housing census 2004 (Demographic Characteristics of the Population), issued by the Central Bureau of Statistics in Yemen. It is noted that the "demographic characteristics" in the report did not include any reference to ethnic diversity within Yemeni society.

4- After the Yemeni "youth uprising" that started at Sanaa University on 11 February 2011, the conference, which is supposed to have brought together representatives of all components of Yemeni society, took place between 18 March 2013 and 25 January 2014.

5- The same interview mentioned above.