This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

“We have phosphate and two seas, but we live with poor means!” This slogan is chanted in every protest, expressing the frustration of a large percentage of Moroccans who do not enjoy the minimum levels of decent living in a country that has abundant natural resources. These resources are almost inexhaustible on Morocco’s land and sea, both under and above ground, and in its waters and extended mountains. These diverse and plentiful resources are supposed to enable the country to acquire economic sovereignty without dependency. But the misuse and mismanagement of these resources threaten their depletion in the coming years.

Morocco’s Waters Spring from its Mountains

The waters of Moroccan rivers spring from the country’s mountains extending from the countryside to the Atlas Mountains. Morocco does not share its water resources with its neighbors like the riparian countries on the Nile or the Euphrates. However, the Moroccan citizen’s average annual share of renewable water resources is in constant decline (1). In the 1960s, the renewable water resources per capita for Morocco was 3,000 cubic meters per year. However, it is expected to drop to less than 500 cubic meters by next year, which is considered the beginning of absolute water scarcity (i.e., the amount of water is less than the minimum needed to meet the needs of the people, according to international standards). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) considered this average a “destabilizing factor,” as its 2018 report warned Morocco and the Middle East and North Africa countries that “instability combined with poor water management can become a vicious cycle that further exacerbates social tensions.” The report called for a “shift away from current policies focused on increasing supplies toward long-term management of water resources. Ineffective policies have left the region’s people and communities exposed to the impacts of water scarcity, growing ever more severe as a result of rising demand and climate change.”

Water supply in the past decades did not include all individuals, and the groups of people whose houses were not connected with piped potable water supply were forced to fetch water through public taps placed in marginal and poor neighborhoods and alleys. These taps no longer exist, or barely exist, after the percentage of individual access to water increased (2) and most Moroccans benefited from their right to water resources for individual and domestic consumption at least. But the quality of water is another issue, which is evident in several places. This is in addition to the severe shortage of water flow and the occasional water outage. Moreover, the distribution of water resources is not equal in most areas of the country (3).

As concern about water depletion rises, the authorities confirm that they are in the process of implementing the National Water Plan. The project aims at constructing three dams annually, desalinating seawater with a capacity expected to reach 510 million cubic meters, reusing sewage water, and diverting water from the basins of the major rivers in the northwest to the center-west basins, with about 800 million cubic meters.

Mineral Water Enriches Companies

Article 1 of the Water Law states: “Water is a public property and may not be transferred to a private property.” However, the law does not object to relinquishing the management of water resources to private companies, which generate profits exceeding 2 billion dirhams (about $200 million) per year, with an annual production of 430 million liters of mineral water.

The companies' revenues do not stem from the large volume of individual consumption of bottled water but the selling price per liter. For example, this is the case of the Sidi Ali water bottles, of which a 1.5-liter bottle is sold for six dirhams, which is higher than the price of other international mineral water bottles in the local market. Moroccans did not like the price imposed by the Olmas Mineral Water Company on the Sidi Ali product. So they resorted to boycotting its products, in an unprecedented move that also affected three big companies.

The company in question is the Holmarcom Group, a family holding company founded by the Mohamed Bensalah family and managed by Mariyam Bensalah. The company did not initially recognize the consumer boycott of its products. For many months, it ignored the matter until it released figures indicating a loss of about $17 million (about 173.8 million dirhams) (4). Before the boycott, the bottled mineral water sector did not face foreign competition due to the high customs duties imposed by Morocco on imported mineral water, amounting to 25 percent of its price, and also due to the difficulty of reaching the local market in the absence of an efficient distribution network. However, Moroccans began to buy Spanish and other imported mineral water products, displaying them on their social media pages as a call for a boycott. It is worth noting that mineral water imports have increased by 45% since mid-2018.

The "Gloomy" Economy of Morocco

15-07-2019

The residents of the village Tarmilat, where the water of the boycotted company comes from, and human rights activists accuse the company of illegally exploiting groundwater resources. According to press reports, the company is involved in completely draining wells (5), which has forced it to drill 11 additional wells to transfer water to the source. This is while the villagers suffer from frequent water outages, especially during the summers when water is not available for more than two hours a day. This situation enraged the residents who participated in protests against the company's business, demanding that it provide them with drinking water, save mineral water, and put an end to the depletion of the area's water resources.

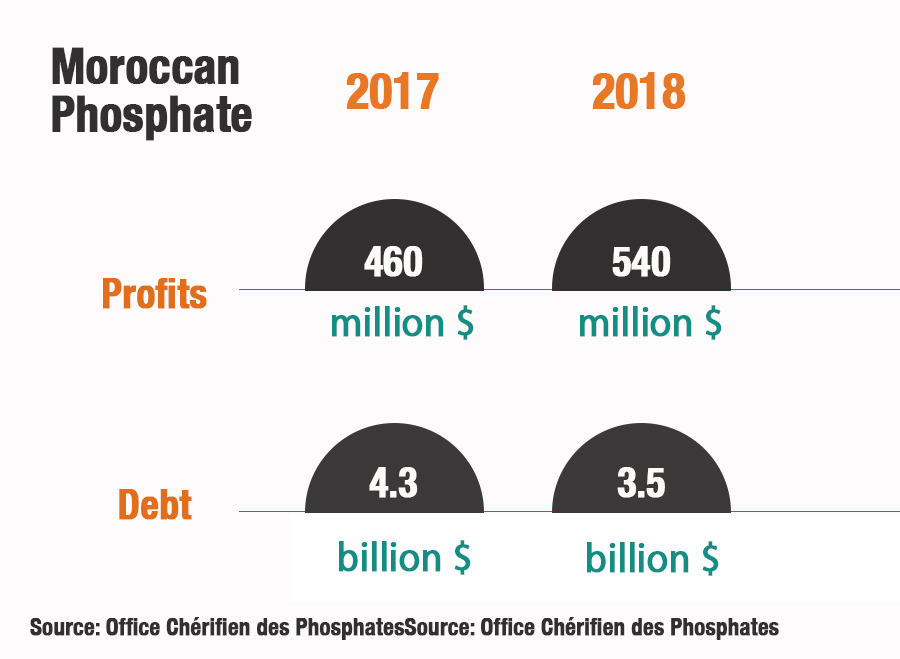

Phosphate: Morocco's Gift with Unknown Profits

Phosphate is Morocco’s gift (6), an underground resource that is indispensable for increasing agricultural production in the whole world. There is no fertile soil without fertilizer and no fertilizer without phosphorous extracted from crude phosphate. Phosphate resources are run by the state-owned company Office Chérifien des Phosphates (OCP), which is a sovereign institution and a "milk cow" for the regime, as Le Monde newspaper once put it. The regime invests the OCP’s revenues to defuse the various political crises the country has known since the 1970s. They were also an important factor in quelling the anger of the Moroccan streets during the protests of the 1980s.

It is still unclear how phosphate revenues are invested. There are no precise details about the size of the embezzled funds, except for what the Moroccan Association for the Protection of Public Funds has declared in 2011: it reported that 10 billion dirhams (about $1 billion) were embezzled from the OCP, whose profits were estimated at $540 million (about 5.4 billion dirhams). Commenting on this, the Northern Miner Journal said those numbers were "suspicious and inaccurate," admitting that the OCP had "money up to its ears," but its resources were "confidential." Furthermore, the OCP does not list its financial transactions on the stock market, which prevents a transparent view of the real numbers of phosphate trade in the country. Also, the OCP does not have an accounting archive, its business deals are not audited, and its production numbers have been illegally inflated.

It is still unclear how phosphate revenues are invested. There are no precise details about the size of the embezzled funds, except for what the Moroccan Association for the Protection of Public Funds has declared in 2011, when it reported that 10 billion dirhams (about $1 billion) were embezzled from the OCP.

Last May, Morocco's Supreme Audit Institution did not dare to present all the details in its report, which sufficed with listing the problems and technical obstacles and giving solutions and recommendations that concern the improvement of the sector. The institution justified its concealment of these facts by saying they were "harmful to the interests" of the OCP.

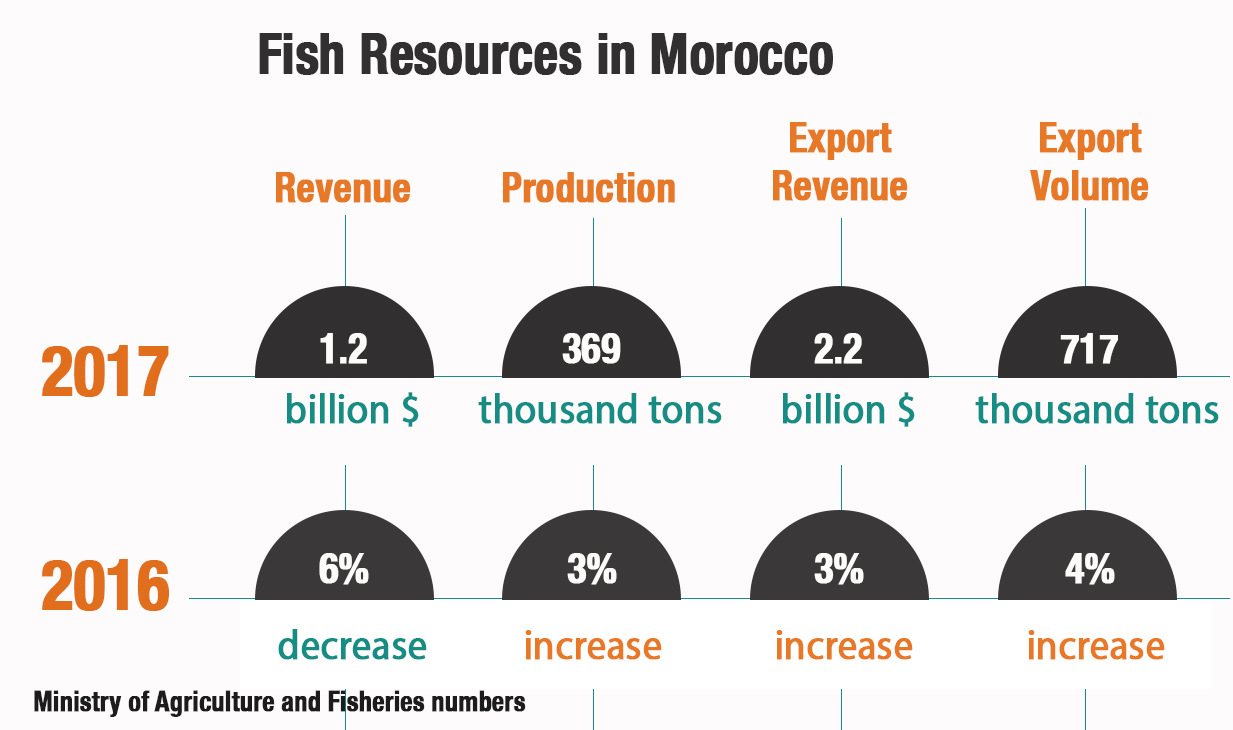

The Country of Fish Eats Very Little Fish

Bordered by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea (7), Morocco has a fish yield exceeding one billion tons annually. It is the first in the Arab world in production and the first exporting country in Africa. Despite this, the average Moroccan consumes between 12 to 14 kilograms of fish per year (most of which is sardine), which is a small amount compared with the global average recommended by FAO (about 17 kilograms), and also compared with the average consumption of countries importing fish from Morocco. For instance, Spain, which has one seafront, has a per capita consumption of 23 kilograms in the worst case.

A partnership between Morocco and the European Union has started in the 1990s as part of the EU-Morocco Association Agreement in various fields, including the fisheries partnership agreement. Proponents of the agreement see it as rewarding. They believe that it pours millions in hard currencies into the state treasury, gives the country opportunities to benefit from the experiences of the European partner, enhances "political and diplomatic cooperation," and defends issues of concern to both parties in international forums, especially the Sahara issue. However, opponents of the agreement believe that it has been “unfair” to Morocco for years, given the “poor” financial return offered by the EU countries to exploit Morocco’s marine resources. In fact, they consider the agreement to be a "submission" to the requirements of the EU and a selling of a vital Moroccan resource at the lowest of prices.

A large number of brokers is a problem adding to the list of obstacles that deprive the local consumer of benefiting from an appropriate price and good quality fish. These people intervene in the details of buying and selling fish, starting from the stage of seaports and ending with the stage of retail selling to street vendors, markets, and fish shops. This image appeared clearly during the past year, as prices showed a large gap between wholesale prices (3.5 dirhams per kilogram) and retail prices (25 to 40 dirhams).

It is not only brokers who are responsible for the high fish prices, the major investors in the sector are also to blame. They forge strong alliances to control the fish price in the local markets. The authority made room for free market selling without caring for the needs of the Moroccan low-income consumer. Therefore, the profit logic achieved its goal, practically and smoothly, in exporting rather than marketing at the local level. There are also other factors that cause the price of fish to rise, including the A to Z costs of fishing. Professionals point out that the prices of fuel, logistics, and labor are also high. In addition, 16 percent of the sale share is always deducted for risk insurance, social security, and local taxes.

Sea Fishery Between Traditional and High Seas Fishing

Most small-scale fishers (or sailors) are not doing well. Their profession is constantly fraught with numerous perils. They earn their livelihood by using small fishing boats (feluccas). Their income depends on the abundance of the easy-to-catch fish. On the other hand, they do not benefit from the risk insurance funds or the compensation for “biological rest” periods (the periods when fishing is banned to allow for fish breeding).

However, the authorities confirm that they have not abandoned sailors, as the government supports them through the Ibhar [Sailing] program, adopted since 2008. However, its implementation faces many obstacles, some of which are administrative and bureaucratic or related to granting loans. Model villages for traditional fishing remain the stable position for this social group. They are located in some coastal villages and provide sailors with more suitable conditions for fishing and infrastructure for receiving and marketing sea products. They provide an organized market for sailors to sell their fish near unloading points, and plants for ice production and fish storage. Model villages also protect the legal status of sailors and grant them social privileges such as enrolling in social security to benefit from its services. However, not all sailors enjoy these privileges. Many still migrate from one sea to another and from disguised unemployment to a temporary change of professions such as practicing crafts related to sea professions or other works that have nothing to do with this field.

The figures released by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries indicated that the coastal and traditional fishing sector profits amounted to about 6.7 billion dirhams (about $670 million) in 2016. The production volume was more than 1.3 million tons, which is a large volume compared with high seas fishing. But if we go into details, we will see that the yields and profits of this dual (coastal and traditional fishing) sector are collected and placed in one basket. This might be intentional to give the impression that the traditional and coastal fishing profits are much greater than the profits of high seas fishing, despite the latter's efficiency and high capabilities. Mixing between traditional fishing and coastal fishing is confusing; the former has its peculiarities and obstacles. It cannot go beyond small sea distances and depths and a two-ton load. As for the coastal fishery, its load can reach 150 tons, and the ships used for it are not the traditional wooden sailing felucca boats.

The profits and privacy of the high seas fishery are revealed by the quality of its fish yields. It excessively targets rare species, such as mollusks and crustaceans (8), which are considered expensive, profitable, and in high demand in international markets. The profits of this type of sea yield are much greater. In 2016, the mollusks revenues were about 3.5 billion dirhams (about $350 million), while the traditional and coastal fishery revenues were about 2.2 billion dirhams (about $220 million). However, the high seas fishery sector depletes fish resources and violates the quota allocated to some fish species, such as the octopus (a mollusk), which has become an endangered marine creature due to overfishing, in violation of the laws and memoranda that determine the permissible quota in each season and period of fishing.

Announcing the names of the corrupt officials was a very sensitive issue, and no one dared to do so. When a Moroccan newspaper published the names of the corrupt figures, it became clear that they belonged to the world of politics and the military and security field. It also appeared that they are influential figures due to their closeness to the head of the state; profiting from this rentier sector was not for free, but was rather “payback”, in return for loyalty and services provided within the framework of intertwined and complex interests that have been in place for decades.

Furthermore, the high seas fishery sector is involved in environmental violations, such as using traditional and unsustainable fishing methods, emptying quantities of unfit fish into the sea, and disrespecting the biological rest periods of sea creatures. However, the revenue of this sector is wasted, and “Morocco does not benefit from it at all,” as emphasized by Muhammad al-Miskawi, chairman of the Moroccan Association for the Protection of Public Funds. In a statement to a Moroccan website, al-Miskawi said: "The beneficiaries of the licenses resort to tricks, including establishing companies that contract with foreign companies which have the means and technology necessary for sea fishing, in exchange for huge compensations that go to foreign banks as well."

During the 2011 demonstrations, Moroccans called for fighting corruption in this sector, holding those involved accountable, and revealing the lists of the beneficiaries of the profits, considering that the sector constitutes a rentier economy. Prime Minister Abdelilah Benkirane said: "Let bygones be bygones," and the government reneged on its promise to expose the clandestine corruption. Those responsible for the agriculture and fisheries sector are also evading any accountability. The topic seemed very sensitive, as no one dared to expose those involved. However, when a Moroccan newspaper (9) published their names, it became clear that they belonged to the worlds of politics, military, and security. It also appeared that they are influential figures due to their closeness to the head of the state; benefitting off this rentier sector was not for free but was rather in exchange for their loyalty and the services they provided within the framework of intertwined and complex interests that have been in place for decades.

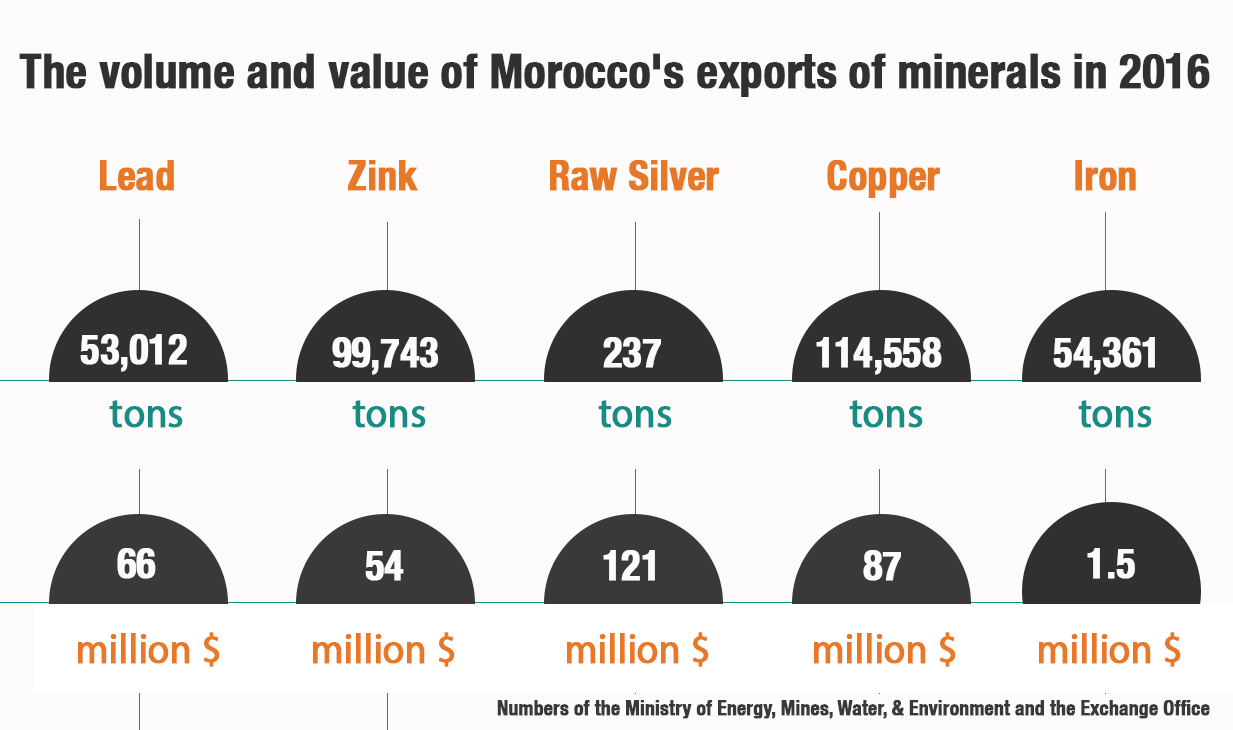

In general, regarding the depletion and mismanagement of natural resources in Morocco, the question of resources is present strongly in Moroccans' everyday meetings and conversations. They are not scarce, as official figures indicate their value amounts to 12.833 billion Moroccan dirhams, i.e., more than $1 trillion (10). So, what if these resources are equally distributed? Certainly then, the voices of Moroccans in the streets and squares would not chant the slogan “we live with poor means,” while “we have phosphate and two seas.” Moreover, the natural resources that revolve in the orbit of the phosphate and the two seas are on the line, risking scarcity and depletion for future generations.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Sabry Zaki

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 18/07/2019

1) According to a report by the World Bank.

2) From 14% in 1994 to 94% in recent years (Economic, Social and Environmental Council).

3) Water per capita in the north exceeds 2,000 cubic meters annually (by virtue of rainfall rates and climatic and terrain factors), while the southern areas provide 150 cubic meters annually for each person.

4) Its financial revenues were 189.5 million dirhams (about $18 million) in 2017, and collapsed to $1.570 million (15.7 million dirhams) in 2018.

5) In Article 112, the Water Law prohibits the exploitation of water in the orbits, as this poses a threat to the water springs or the quality of water.

6) Reserves of 50 billion tons, or about 71% of global reserves.

7) Morocco overlooks two sea fronts, with a coastline of 3,500 km in length, of which 2,900 km on the Atlantic Ocean, and 600 km on the shores of the Mediterranean, with a sea area of 115,000 km².

8) According to figures from the marine fishing sector, the price of red shrimp per kilogram reached 58.52 dirhams, while the price of royal shrimp reached 143.29 dirhams per kilogram during 2017.

9) The names were published in Akhbar al-Yawm newspaper on 8 March 2012. They are leaders in the royal gendarmerie, the army, and the worlds of politics and economics.

10) The figures and statistics of the Economic, Social and Environmental Council confirm that natural resources, which include agricultural and grazing lands, forests, fisheries, mineral and energy resources, and protected areas, have doubled by 2.4 percent in 15 years.

(*) The dollar exchange rate ranges between 9-10 Moroccan dirhams.