This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The Covid-19 virus has brought the entire human race face to face with the shape of their reality. While humanity at large is in one boat and faces one threat, it has deeply disparate capacities to face it. As “We are only as strong as the weakest health system,”(1) this new pandemic cannot be eradicated but through solidarity and cooperation – to guarantee the best humane response possible to fight the virus.

In April 2020, and in cooperation with the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the World Health Organisation (WHO) rolled out the COVAX initiative. COVAX is an international mechanism designated to guarantee fair access to Covid-19 vaccines globally through vaccinating people in impoverished countries and middle-income countries incapable of signing bilateral agreements for vaccine presales. Syria is one of those countries.

Initiative organisers announced their target of providing more than two billion doses to 92 countries in need by the end of this year (2021). The programme faced many challenges, however, related to underfunding, bureaucratic hurdles, or rich states’ tendency to buy most new vaccines. Until June 2021, COVAX contributed no more than 4 percent of more than two billion shots administered worldwide. The programme still needs at least half a billion doses to achieve its primary goal.

Across lines of conflict

WHO has listed Syria among the low-income countries that would be administered their own share of vaccines through COVAX. War has cast its shadow on the process since day one, however. While the official government made its COVAX application on December 15th, 2020, the ruling authorities in northwest Syria made a separate vaccine application, to be supplied to those territories under its control. The remaining areas in northeast Syria, however, would be left without any arrangements for a separate vaccine supply.

Even before vaccine doses were administered, Human Rights Watch (HRW) expressed its concern about the logistical challenges that stand between providing and distributing the vaccines across Syria. Several types of vaccine require specific storage and distribution conditions, including “cold chain management”. This creates an extra burden to a country where conflict, deteriorated living conditions, and altogether damaged infrastructures prevail. It also noted the importance of guaranteeing the most comprehensive and fairest vaccine distribution all over Syria, including all areas controlled by different groups. It stressed that “Although the Syrian government bears primary responsibility for providing health care to everyone in its territory, it has repeatedly withheld vital food, medicine, and aid from political opponents and civilians”.

HRW noted that withholding healthcare is here used as a weapon of war, reiterating its previous documentation of the discriminatory distribution of Covid-19 equipment, even in areas under complete government control. It also recommended that humanitarian agencies should apply pressure to ensure a fair distribution plan and provide independent monitoring of vaccine supplies and administration.

Despite all efforts, Syria generally still ranks as one of the least vaccinated countries in the world. The latest available statistics indicate that, by the beginning of July 2021, the number of vaccine shots given in Syria has exceeded 355 thousand. This would only vaccinate one percent of the population, whereas, according to the latest WHO statistics, half the world’s countries have managed to vaccinate 10 percent of their population.

As camps have been multiplying across Syrian territories, the need for vaccines has grown. A decade of strife unfolded in the biggest crisis of displacement ever seen since World War Two. UN estimates show that 6.6 million people have migrated abroad, while 6.7 million have been internally displaced. The latter category, especially its camp residents, is considered to be the most affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and its implications. They live in an environment that lacks the most basic healthcare determinants and life essentials, where it is difficult to apply any of the recommended measures to prevent a viral spread.

In a UNICEF report in May 2021 titled Lost at Home, internally displaced children were considered to be among the most vulnerable to the direct and indirect impacts of Covid-19. While they lack access in the first place to the bare minimum of basic services, Covid-19 has been making the critical situation for internally displaced children and their families even worse.

Regime-controlled areas: an overarching lack of data

On April 22nd, 2021, the regime’s Ministry of Health announced the arrival of the first batch of Covid-19 vaccines through the WHO-backed COVAX initiative, which contained 203 thousand AstraZeneca doses from the Serum Institute of India. The ministry also quoted the promises of the Ambassador of India to Damascus that more batches would arrive in Syria through COVAX as well.

Contrary to the WHO-administered batch, a number of reports mentioned that the Syrian regime had received different batches of the vaccine. Some such reports matched statements issued by Syrian officials who said that the vaccines were received, while others received no media coverage from the Syrian end, or were rather announced without sufficient instructions on vaccine distribution, rollout, or targeted groups.

Emirati news agencies noted several reports on the arrival of four Emirati airplanes loaded with Covid-19 vaccines into Damascus. They were brought in by the Emirati Red Cross, in coordination with the Syrian Red Cross. The first plane arrived on April 20th, while the last arrived on May 4th. The reports did not provide enough details about the vaccine shipment, barring their description that vaccine quantities were “large”.

The Ambassador of Syria to Moscow said that Syria received the first shipment of the Russian Sputnik V vaccine, according to reports by the Russian news agency, Interfax, in early June 2021 – but with no clarification on shipment size. Sputnik Agency then followed up with a report on July 25th, in which the Russian Ministry of Defence announced handing over 250 thousand Sputnik Light doses aboard a Russian air force cargo airplane, along with diagnostic testing kits.

According to Syrian officials, the Syrian Ministry of Health also received 150 thousand Sinopharm doses, offered by the Chinese government on April 24th, 2021. Later, China sent yet another shipment containing 150 thousand Sinopharm doses on July 29th. The Chinese Foreign Minister also pledged to offer “a new batch of vaccines, containing 500 thousand doses”, according to Sana News Agency.

On May 5th, the Syrian Ministry of Health announced that it launched an e-platform to register requests by those who wished to receive the Covid-19 vaccine. It noted that the vaccines were offered for free and that priority would be given to doctors, nurses, and healthcare workers, followed by groups deemed vulnerable, like the elderly and those with chronic illnesses. A member of the Covid-19 advisory team announced to the local radio, Sham FM, that the Ministry of Health had allocated the Russian and Chinese vaccines to doctors and individuals under 50, and AstraZeneca to those over 50, especially those who suffer from chronic illnesses.

The Syrian Ministry of Health also noted that it has assigned 81 centres for vaccination, specifying their names and addresses. Those were dispersed across the different governorates: 10 main centres were designated in Damascus, 16 in Tarsus, 12 in Rif Dimashq Governorate, 11 in Aleppo, 6 in Hama, 5 in Latakia, 4 in al-Hassakah, 3 in each of Raqqa, Dar‘aa, Quneitra, Homs, Al-Suwayda, and one in each of Deir-Zour and Idlib.

Although vaccine shots arrived to Syria free of charge, the Syrian Prime Ministry issued a decision that stipulated paying a fixed fee by anyone who wished to receive a certificate of vaccination, like a “service fee”. This constitutes an additional burden to a country with more than 80 percent of its population under the poverty line, according to UN estimates.

A doctor working in one of the Damascus hospitals told us that that overall vaccination turnout is still low, adding over the phone that “people spread many rumours among themselves about the AstraZeneca vaccine and its side effects. They have many concerns, while trust in healthcare officials does not suffice to contradict such worries. Unfortunately, vaccination rates are still very low.”

Although vaccination data is digitised, Syrian authorities have yet to issue any official statistics on the number of vaccinated individuals. Media blackout prevails over most questions related to the vaccination rollout. The latest WHO statistics published on Our World in Data website indicate that more than 112 thousand people in Syria have received at least one vaccine shot, which, according the website, amounts to 0.6 percent of the population.

Such severe lack of data seems to match the approach of the official Syrian authority in the way it generally treated the Covid-19 pandemic since its start (2). In March and April 2020, the regime’s response went nowhere beyond some precautionary measures, which were quickly lightened. The overall response was full of discrepancies, secrecy, and an inability to provide most of the main requirements for protection.

Northeast Syria: the smallest share

The region of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria were most unfortunate in questions of Covid-19 vaccines. The agreement with COVAX created regional policies and challenges, as it stipulated sending the region’s share through Damascus. It would later be transported and distributed in north and east Syria under the supervision of WHO.

In March 2021, WHO Syria announced (3) that 90 thousand doses would be allocated to the northern regions of the country. Mobile teams would reach camps that housed tens of thousands of displaced persons. Autonomous Administration officials considered these numbers to be too small, however, compared with the number of people in these parts of Syria – nearly 5 million people – especially with the large numbers of displaced persons in camps within those regions.

The first batch only arrived on May 29th 2021, which contained 17,500 AstraZeneca doses, with promises to send more later. 13,200 doses would be distributed in Al-Hassakah, 4 thousand in East Rif Deir Zour, 6 thousand to Raqqa Governorate. This is considered the first time that this UN organisation directly provided medical supplies to the area.

The Health Authority of the Autonomous Administration stated that it would adopt a plan to administer vaccines through its own healthcare centres, and through its medical units in displaced persons camps. Accordingly, vaccine shipments were then announced into local hospitals and healthcare centres.

According to a joint statement by the Health Authority of North and East Syria, (4) a vaccine batch was supposed to arrive much earlier than that: “WHO sent 203 thousand doses to the Syrian regime in early May, one batch of which was designated for northeast Syria and supposed to arrive from Damascus Airport to Qamishli. The quantity that reached the region, however, turned out to contain a mere 645 doses. It added that the region needs “nearly one million vaccine doses”.

Such delay came as the region was exposed to one of the worst periods of the second Covid-19 wave, underfunding, and a struggle to find essential treatment supplies – according to a report issued by Doctors without Borders in early May 2021. This was especially the case as no border crossing through the UN was allowed; it was thus difficult to deliver aid. The region also suffered a severe lack of services in the shadow of a growing outbreak.

On August 4th, 2021, Jowan Mustafa reaffirmed that the Health Authority of North and East Syria had not received any new doses from WHO, barring the first one, which amounted to 23 thousand doses – insufficient for covering the region’s needs. He warned that the fourth Covid-19 wave could possibly be upon the region – equally dangerous and spreads fast.

Northwest Syria…under UN sponsorship

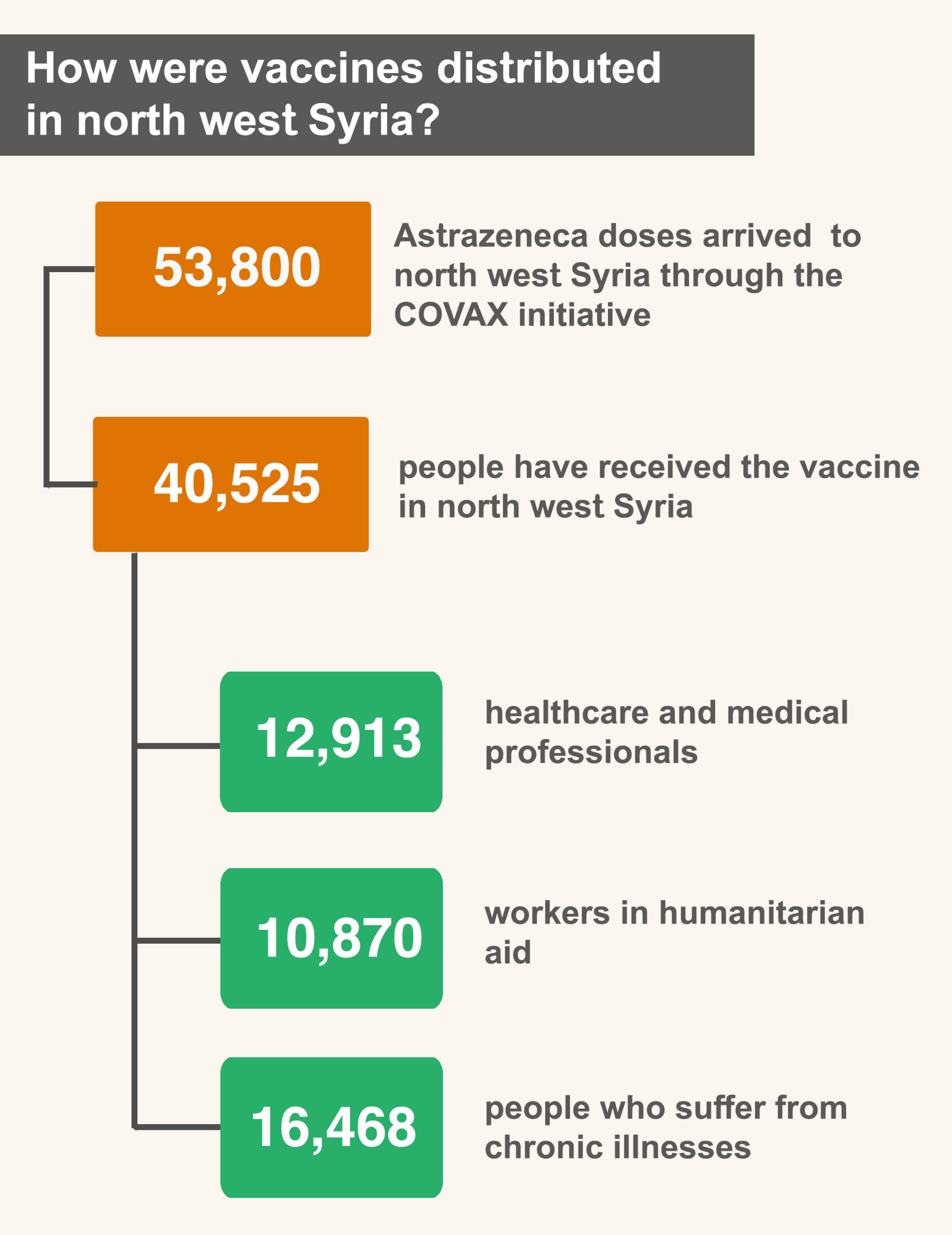

Through Bab al-Hawa crossing, bordering Turkey, the first batch, which 53 thousand and 800 AstraZeneca doses, arrived in April 2021 into northwest Syria – as part of the COVAX initiative. The vaccination campaign is still limited to the first category of elderly people, people with chronic diseases, and humanitarian workers. In coordination with the region’s local councils, the Syria Immunization Group publishes the latest updates about vaccination centres, including hospitals, fixed health centres, as well as mobile medical teams.

On July 9th, 2021, the pandemic observatory, affiliated with the support coordination unit, announced that in northwest Syria, 40 thousand and 525 people had received the Covid-19 vaccine, 12 thousand and 913 of which are healthcare workers, 10 thousand and 870 of which are humanitarian workers, and 16 thousand and 468 of which are people with chronic diseases.

All over Syria, hesitation and rumours marked the first vaccination phase. Media coverage and awareness campaigns launched by northern healthcare authorities, however, were more transparent and detailed than their counterparts. The Syria Immunization Group, which cooperates with healthcare departments and answers to WHO and UNICEF, devoted themselves to publishing reassuring materials that urged people to take the vaccine. The Support Coordination Unit also continued to issue weekly reports that contained everything related to the spread of Covid-19, including vaccine recipients follow-up and observing any side effects that they might experience.

***

Generally speaking, vaccination numbers throughout Syria’s regions are particularly far behind what WHO had hoped they would be – namely, covering nearly 20 percent of the Syrian population by the end of 2021. The vaccination campaign in Syria is thus still lagging behind in terms of quantity and distribution, all in an environment shrouded by waiting and the unknown.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 02/09/2021

1) UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ remarks.

2) Afaf al-Hajji. “Syria: the image of a country torn by war, one year into Covid-19”

3) According to Reuters.

4) Mr Jowan Mustafa to Hawar News Agency.