This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

The Arab Mashriq had been fraught with turning points even before the 9/11 attacks in 2001. Hafez al-Assad had departed with Rabin’s “deposit” leading nowhere, with no peace on the horizon that would restore Syrian sovereignty in the Occupied Golan Heights. Hafez’s son, Bashar succeeded him, with clear support from the French President at the time, Jacques Chirac, and Rafic Hariri’s intervention. The latter had reassumed his position as Lebanon’s prime minister, despite the beginning of the country’s financial downturn that forced him to resign. Israel withdrew from Southern Lebanon, leaving the Syrian army in an uncomfortable position as the only remaining “occupying” force. Despite their uselessness at the time, the Syrian security forces possessed sweeping influence in Lebanon. While Iraq was being stifled by US sanctions, Syria and Lebanon were benefitting from the UN Oil-For-Food Programme (OFFP), even manipulating its measures.

9/11 and pre-invasion

Then, in 2001, 9/11 happened. It wasn’t clear, however, whether every party in the Mashriq had truly realised the implications that those attacks would unfold, especially under an already arrogant and cynical US administration. Consequently, a US-led ‘tempest’ of revenge appeared on the horizon of the whole region, with its first stop being the invasion of Iraq.

Notably, in Syria, those attacks coincided with the crackdown on the "Damascus Spring", where a certain political freedom policy was adopted with the arrival of the young president. Baath party officials and figure heads were influenced by the spirit of the "spring" and began to severely critique the ruling regime. In parallel, the US Secretary of State Colin Powell communicated with President al-Assad, the US was escalating its warnings against smuggling Iraqi oil. This occurred while the Syrian security forces closely worked with US intelligence to monitor and arrest Al-Qaeda operatives in “America’s war on terror”. It is equally worth noting that the Paris II conference was then held, under the auspices of the French government, in November 2002. It aimed to implement the promises of the Paris I conference and secure funding to bolster Lebanon’s economy against financial collapse.

The implications of the invasion in Syria

Preparations to invade Iraq unfolded. France played a leading role in the efforts to stop the Security Council from reaching a resolution that would justify and sanction the invasion. Syria lined up behind France, contrary to the position Hafez al-Assad assumed in 1991, where he pro forma took part in the Gulf War alliance. Baghdad eventually fell in April 2003. As US forces arrived at the Syrian borders and threatened to continue all the way to Damascus, Michel Aoun, and other lobby groups, took the opportunity to push for US sanctions on Syria under the Syria Accountability and Lebanese Sovereignty Restoration Act.

The strategic trap set up by the Israelis worked. The Syrian army withdrew, humiliated, in April 2005. Rafic Hariri had already been assassinated in February 2005. Others fell victim to this trap and the interregional geopolitical conflicts that the invasion of Iraq caused.

The atmosphere in Damascus became tense. A Syrian immigrant in the US was visiting Syria in the summer of 2003. Sitting in a local restaurant, she spoke loudly on the phone with her son, whom she had pushed to join the US Marine Corps, thinking that would help him overcome his drug addiction. Her son was close to her, serving at the Iraqi borders, but his army commander wouldn’t allow him to visit her in Syria. Her friend sarcastically commented: “They won’t let him come alone; they’ll have the entire US army enter Damascus with him!” Another lady, who had never travelled abroad, watched from her balcony as a Syrian official’s son and his men attacked a young man from the neighbourhood, only because his car was standing in the way of their convoy. She yelled before the gathering crowds: “I hope the Americans come and save us from you, as they have done in Iraq!” Those are scenes and words that were virtually impossible to imagine in Syrian minds before.

Soon, the US occupation was tampering with Iraq, showing leniency towards Iran and putting severe pressure on Syria. Bashar al-Assad asked Jacques Chirac for help, by trying to speed up a partnership agreement with Europe that the two countries had long hindered. However, there were two significant stumbling blocks: the first was the Syrian regime’s lack of desire to liberalise the communications sector, controlled by the Makhlouf family (Bashar al-Assad’s relatives) and the Mikati family (Lebanon’s current prime minister); while the second was that Europe insisted that Syria, but not Israel, pledged to abandon any weapons of mass destruction.

France: major ally to lead opponent

The negotiations were doomed to fail in any case, however, as France was also under US pressure due to its position on the invasion of Iraq. As such, a rift was formed between Syria and France, with contradicting interpretations of the reasons behind it. France spoke of a gas agreement that the Syrian authorities refused to give to Total Energies, knowing that it was part of a larger project that the French authorities had halted in the mid-1990s and that the newly implemented US sanctions would impede its realization anyway. Additionally, the French authorities denied entry to a French-Lebanese bank to the first wave of private banks in Syria in 2004, despite the fact that establishing private banks was one of the most significant expressions of economic openness adopted by the new presidency, under the premise of “economic reform precedes political reform”.

In fact, France’s opposition to the Security Council’s adoption of the resolution to invade Iraq had a significant effect on US-French relations. Americans boycotted French goods and changed the name of “French Fries” to “Freedom Fries!” Such historic rift between the two countries would only be contained a year after Baghdad fell: first in June 2004, during D-Day commemorations in Normandy, then at the G8 Summit on Sea Island, off the coast of Georgia. One of the main ways to restore those relations was an agreement between Jacques Chirac and George W. Bush to “re-establish Lebanon’s independence and sovereignty.” And so, cooperation began by issuing the Security Council’s Resolution 1559, which would call for all foreign forces to withdraw from Lebanon (mainly the Syrian army) and for disbanding and disarming all Lebanese militias (Hezbollah being intended).

Dealing with the seismic events of 2001 and 2003 wasn’t easy on the political opposition either, which had begun to gain momentum with the dawn of a new political era in Syria. The biggest challenge the opposition faced, however, was juggling the criticism of the government’s socio-political practices, and its former and current approaches, with growing sectarianism and religious extremism, and with the regional and international shifts.

Just a few months earlier, Chirac had linked, in his speech before the Lebanese parliament, the Syrian army’s withdrawal with Israel’s withdrawal from the Shebaa Farms. As such, the shift in France’s position – which also stemmed from Chirac’s “giving up” on Bashar al-Assad’s rigidity and lack of initiative to address the implications of the invasion of Iraq – finally led to a political “earthquake” across Lebanon and Syria.

Hariri’s assassination and the Syrian withdrawal

It appears that the Syrian regime knew about the agreement between Chirac and W. Bush even before voting on the Security Council resolution, and so chose direct confrontation in Lebanon. Headed by Rafic Hariri, Lebanese deputies then backed a constitutional amendment that allowed for then President Émile Lahoud to extend his term in September 2004. Hariri voted in parliament for the amendment “so that Syria isn’t humiliated in Lebanon”. He later resigned as prime minister in October 2004.

This is how the strategic trap set up by the Israelis worked. The Syrian army withdrew, humiliated, in April 2005. Rafic Hariri had already been assassinated in February 2005, while others fell victim to this trap and the interregional geopolitical conflicts that ensued as a result of the US invasion of Iraq.

Impacts of Iraq’s civil war on Syria

The developments in Iraq were no less seismic. The UN Special Representative for Iraq, sent by the UN after the collapse of the Iraqi state and the disbanding of the Iraqi army, was assassinated. A series of sectarian and “resistance” bombings thus began against the occupation. Shiite militias appeared, backed by Iran, while an alliance was formed between Al-Qaeda and the rest of the former Iraqi military and security personnel. The Iraqi civil war broke out.

Saddam Hussein’s arrest in December 2003 impacted the Syrian Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia, bordering Iraq). In a soccer match in Qamishli in March 2004, Deir Ezzor team fans (Ftuwwah) raised Saddam Hussein’s photos in the face of Kurdish Qamishli fans (Al-Jihad), who, in turn, raised signs that said: “We’d give our lives for Bush!” This unfolded in violent clashes that spread throughout the city and lasted six days. Syrian security forces and the army had to intervene, and dozens of people, mostly Kurds, fell victim to the violence. Thousands of Syrian Kurds thus sought refuge in Iraqi Kurdistan, while sectarian and ethnic conflicts spilled over from Iraq into Syria.

Even before the invasion, Syria (and Jordan) began to see waves of Iraqi refugees. Their numbers increased significantly following the battle of Fallujah, and especially after the bombings of the Shrines of Imam Ali al-Hadi and Hassan al-Askari in Samarra in 2006. By 2007, the number of Iraqi refugees in Syria had reached 1.5 million Sunni, Shiite, Christian, Assyrian, and Yazidi refugees.

In fact, Syria embraced, along with the rest of the region, the logic of “creative chaos” and the so-called “New Middle East” (!), which was being reshaped based on the politics of the US administration, as declared by the US Secretary of State at the time, Condoleezza Rice, starting from Iraq, then Lebanon and Syria.

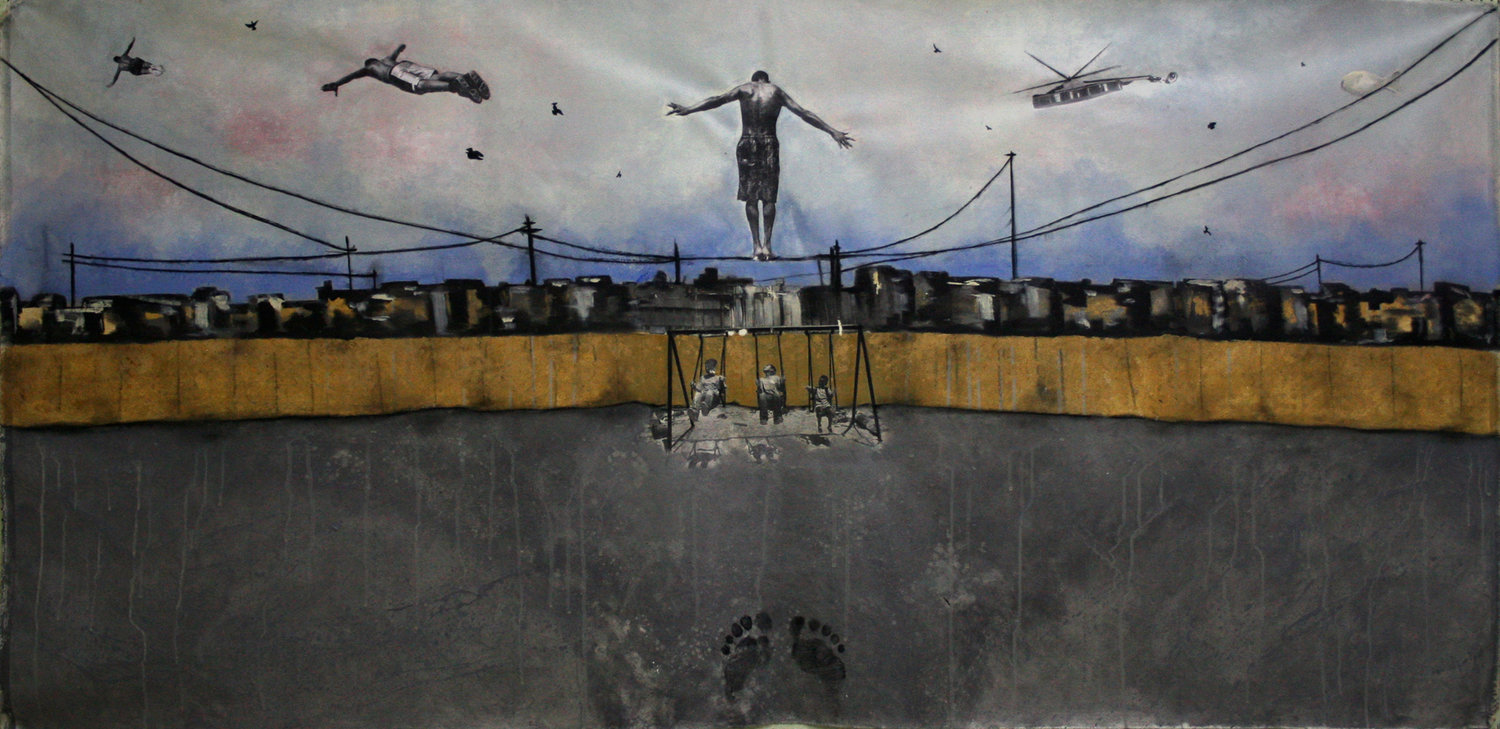

I Am All of These Dead Faces

01-09-2023

However, in September 2006, the Syrian security forces thwarted an attempted bombing of the US embassy in Damascus, which was allegedly planned by al-Qaeda-backed Jund al-Sham. The incident somehow restored US-Syrian relations, though the US administration accused Syria of facilitating access of fighters and arms into Iraq. The situation looked extremely complicated: Syria, an ally to Iran, was also cooperating with Saudi Arabia to support Sunni “resistance” in Iraq.

On the other hand, Syria (as well as Jordan) began to witness waves of Iraqi refugees, starting even before the invasion. At first, small numbers of influential, well-to-do, and middle-class Iraqis began to arrive. They headed to Syrian cities where they joined those Iraqis who had already fled the oppressive regime of Saddam Hussein and his men. However, in 2004, the numbers saw a significant increase, following the battle of Fallujah, and again in 2006, after the bombing of the Shrines of Imam Ali al-Hadi and Hassan al-Askari in Samarra. By 2007, the number of Iraqi refugees in Syria had reached 1.5 million, and included Sunni, Shiite, Christian, Assyrian, and Yazidi refugees (in the aftermath of the battles with the Iraqi Kurdish forces near Mosul). Huge refugee camps were set up for Iraqi refugees of popular classes in the Syrian Jazira, what had significant repercussions on Syria’s economy.

Turkey and Qatar: Syrian allies?

Amidst all these turning points, Turkey invited Bashar al-Assad to visit in January 2004. It was the first visit that a Syrian president had paid to Turkey since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The Turkish parliament had refused to make use of its territories or its NATO military bases to invade Iraq. That same year, Turkey’s then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan visited Syria to sign a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the two countries. Despite strong US opposition, Turkish president Ahmet Necdet Sezer followed suit, visiting Syria in April 2005, during Lebanon’s "Cedar Revolution", in the wake of the assassination of Rafic Hariri. Such a regional political earthquake couldn’t have happened without the invasion of Iraq, even if those moves were theoretically grounded in the advice of Ahmet Davutoglu, then advisor to the prime minister, of adopting the principle of “zero problems towards neighbours.”

Turkey, blocked from joining the EU for fear that it would end up “bordering Syria and Iraq”, set out on a policy of adopting a free movement of goods and individuals with neighbouring countries. Turkey’s policy depended on Syria to overcome the conflict with the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), and on Iraq, whose production capabilities collapsed and became dependent on the competing Iran and Turkey for the majority of its supplies. Turkey also targeted Iraqi Kurdistan, specifically because of its relative stability and impact on the Kurdish question. It also established a solid economic cooperation with Iran.

The Syrian-Turkish rapprochement accelerated with the breakdown of the EU-Syria partnership agreement talks, followed by the fallout with France. In 2007, the FTA between Syria and Turkey came into effect, with major repercussions to the detriment of the industrial sector in Aleppo, which was not on a par with Turkish production and unprepared to compete with it. Bashar al-Assad paid an official visit to Turkey, which was followed by Turkish mediation for Syrian-Israeli negotiations, with the aim of normalizing relations between the two countries and resolving the question of the occupation of the Golan Heights. Turkey’s mediation efforts began following the Israeli assault on Lebanon in 2006 and collapsed following the Israeli assault on Gaza in 2008, resulting in the deterioration of Turkish-Israeli relations. In April 2009, Turkey and Syria conducted joint military maneuvers, which were followed by a visit from President Abdullah Gul to Syria.

The international climate changed, as the EU was experiencing its own challenges. In 2007, French president Nicolas Sarkozy launched a Union for the Mediterranean (UfM). And in 2008, Bashar al-Assad was invited to attend the national celebration of the 14th of July in France, as Turkey brokered the Syrian-Israeli negotiations.

In parallel, as soon as he began his term, the Emir of Qatar Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani and his prime minister Hamad Bin Jasim consolidated their relations with Bashar al-Assad. It seems that these relations weren’t significantly affected by the US army’s intensive use of the Khawr al-Udayd air base in their invasion of Iraq. Rather, such relations strengthened with France’s change of position and the deteriorating relations between al-Assad and Saudi Arabia, following the extension of Lahoud’s term in Lebanon and Rafic Hariri’s assassination. The Prince of Qatar even began the construction of a huge palace on a hill on the road between Damascus and Beirut. Additionally, Qatar played the role of a mediator during the Israeli aggressions on Lebanon in 2006 and Gaza in 2008. At the time, the Qatari Prince seemed unbothered by Bashar al-Assad’s description of the leaders of the Gulf and Egypt as “half men”.

The "Islamic State" and the reconciliation with France

“Creative chaos” in Iraq backfired on the US army, which began to suffer many human losses and critique, especially as the Islamic State emerged. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi formed an alliance with al-Qaeda, run by Oussama bin Laden, who together founded al-Qaeda in Iraq, which became an umbrella organization for many others. Together, they controlled large expanses of Iraq, extending from Mosul to al-Anbar to Diyala Governorates, all the way to Baqubah, their “capital” city, close to Baghdad. Although al-Zarqawi was killed in 2006, the US administration deposed Donald Rumsfeld, who engineered the invasion of Iraq, and executed Saddam Hussein, while significantly increasing the number of its troops in Iraq and establishing militias of Sunni tribes, known as “Sahwat” (“the Awakenings”). It was apparent that Iraq had become a quicksand swamp with the US itself sucked into its chaos.

Ommetaphobia: The Gouged Eyed of Childhood

24-09-2023

The Generation of Loss

19-09-2023

The international climate thus changed, as the EU was experiencing its own challenges. In 2007, the newly-elected French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, launched a Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), which aimed at “guaranteeing peace, stability, and prosperity” for nations at the shores of the Mediterranean, whose peoples’ fates are linked. The project obviously included Syria and Israel. And so, in 2008, Bashar al-Assad was invited to attend the national celebration of the 14th of July in France, as Turkey brokered the Syrian-Israeli negotiations. Three months later, Barack Obama, who promised the complete withdrawal of US troops from Iraq, was elected President of the United States.

Iraq and the Syrian regime, opposition, and society

To Bashar al-Assad, dealing with the 9/11 aftermath and the implications of the invasion of Iraq wasn’t an easy feat. The apparatus of power that he had inherited from his father was in a transitional and unstable phase, as Syrian society woke up from a long slumber with the “departure of the dictator” and the “Damascus Spring”. The country was also transitioning from state capitalism to crony capitalism, which Bashar al-Assad worked on establishing in line with the economic zeitgeist. Although no real competition threatened al-Assad’s presidency in the foreseeable future, the domestic open-door policy was swiftly aborted due to the confusion in decision-making processes regarding power structures, Baath party, and external challenges.

While the beginning of Bashar’s term was characterised by a positive domestic climate, the young president failed to take advantage of it to achieve a “national reconciliation” that could heal the wounds caused by the Hama and Palmyra events (1979-1982). Likewise, in 2004, following the Qamishli events, al-Assad failed to resolve the Kurdish question in Syria, which had been pending since 1962. He faced his father’s old guard, who were involved in the corrupt dealings of the Lebanese warlords, but couldn’t draw a vision or stance regarding the burgeoning financial collapse in Lebanon and its internal political repercussions. He also thwarted the liberalisation approach within the Baath party in 2005, in an aim to keep the latter at the disposal of the power and security apparatuses.

Bashar al-Assad fell into the trap set by the Israeli withdrawal from Southern Lebanon in 2000. A deliberate Syrian withdrawal from Lebanon, however, could have ensured continued Syrian influence in Lebanon; this influence being initially greenlit by the United States. He remained motionless with the US invasion of Iraq and its aftermath, despite the event leading to a seismic destabilization of the region as one of the most important Arab countries collapsed.

Al-Assad also wagered on a confrontation between France and the United States, even though it was baseless, despite the “folly” of the US administration in invading Iraq. Likewise, while his father ensured stability by assuming a balanced approach to both Saudi Arabia and Iran, Bashar opposed Saudi Arabia. Still, the invasion of Iraq and growing Iranian influence there would have inevitably led to a clash between the two countries.

Syrian society was experiencing a “youth tsunami”, marked by massive numbers of young people looking to join the job market and a mass migration from rural to urban centers. Large numbers of Syrian Jazira residents migrated into other provinces. Although Syria had paid off its foreign debts and maintained notable foreign currency reserves, no solution was initiated to the pressing social and economic questions.

Dealing with the seismic events of 2001 and 2003 wasn’t easy on the emerging “political opposition” either, which had begun to gain momentum with the dawn of a new political era in Syria. The opposition parties had inherited a 1950s discourse of ideology and divisions, but sought to liberate public discourse through the "Tuesday Seminars of the Economic Sciences Association", the "Atassi Forums", and the "Committees for the Revival of Civil Society". The biggest challenge the opposition faced, however, was juggling the criticism of the government’s socio-political practices, and its former and current approaches, with growing sectarianism and religious extremism, and with the regional and international shifts.

The opposition tried to address the Hama events by advocating for rapprochement with the Muslim Brotherhood, but the latter chose to join the old guard (Abdul Halim Khaddam, who defected from the power system following Rafic Hariri’s assassination), before the Brotherhood moving into direct conversation with the power, hoping to normalize with it. The opposition then opened up to Lebanese movements (The Damascus-Beirut Declaration in 2006), ignoring the particularity of Lebanon and the exploding regional conflict at the time. Some of its leaders also fell into sectarianism, already pervasive in Lebanon, and exacerbated by the civil war in Iraq.

In the meantime, Syrian society was experiencing a “youth tsunami”, marked by massive numbers of young people looking to join the job market and a mass migration from rural to urban centers. The suburbs of major cities became overcrowded due to the influx of newcomers. Large numbers of Syrian Jazira residents migrated into other provinces. However, although Syria had paid off its foreign debts and maintained notable foreign currency reserves, no solution was initiated to the pressing social and economic questions.

The invasion of Iraq thus deepened the existing gaps within the Syrian power, within the opposition groups, and in the society at large. Those gaps were some of the main factors that led to the Arab Spring’s mutation into a civil war in Syria. The impacts of the invasion continue to affect the region, plunging Syria’s future, territorial integrity, and regional status, as well as those of Lebanon and Iraq, into the unknown.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 31/08/2023

The folder “Twenty Years since the War on Iraq” is a joint production between Assafir Al-Arabi and Jummar, with the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.