This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

On May 8th, 2020, the Egyptian Ministry of Health announced that the number of coronavirus cases exceeded 236 thousand, among which 1,123 had just been confirmed that very day. By then, the overall number of deaths was 13,845. (1)

This is a difficult number to process. It cannot be decontextualised, however, from early statements issued by the Minister of Higher Education during the first wave in June 2020, where he said that the real number of cases in Egypt was no less than 5 times the announced number. He explained that screening all citizens was impossible and that, accordingly, the entire world opted for a statistical model capable of mathematically envisioning the sequence of the viral spread. Based on WHO estimates, no less than 20 percent of Covid-19 patients required medium and intensive healthcare, while 5 percent depended on ventilators.

In light of that, one could say that the current number of infections in Egypt might be no less than one million and 300 thousand cases, that is, more than 1 percent of the population, were we to follow that statistical model. Tens of thousands of them required various healthcare services, to be provided through a system that was already under intense pressure.

In one year, Covid-19 cases thus joined other numbers that cannot be accurately enumerated, but that could be guessed in terms of important pertinent indexes. According to a recent official count that the National Cancer Control Plan conducted and announced in 2006, 113 out of every 100 thousand Egyptians have cancer. That is, the overall number within the Egyptian population indicates more than 100 thousand patients. (2) The number of monthly dialysis patients is more than 50 thousand; there are around one million cirrhosis patients, and nearly 1.8 patients who suffer heart failure.

Egypt’s hospital map has generally suffered a sharp decline in recent years. The numbers of hepatitis hospitals dropped from 100 to 32, and the number of governmental hospitals dropped from 1,179 to 681 in ten years’ time – from 2007 to 2018. The number of private hospitals that same year reached 1,157 – having been 686 in 2008.

Waitlisted general and urgent surgeries amount up to 400 thousand, especially with a growing number of traffic accidents, which reached, according to an official count in 2020 alone, more than 16 thousand accidents. (All these numbers are stated and documented by official bodies, like the National Treatment Programme of Hepatitis, the Egyptian Kidney Association, and official WHO reports on the situation in Egypt). (3)

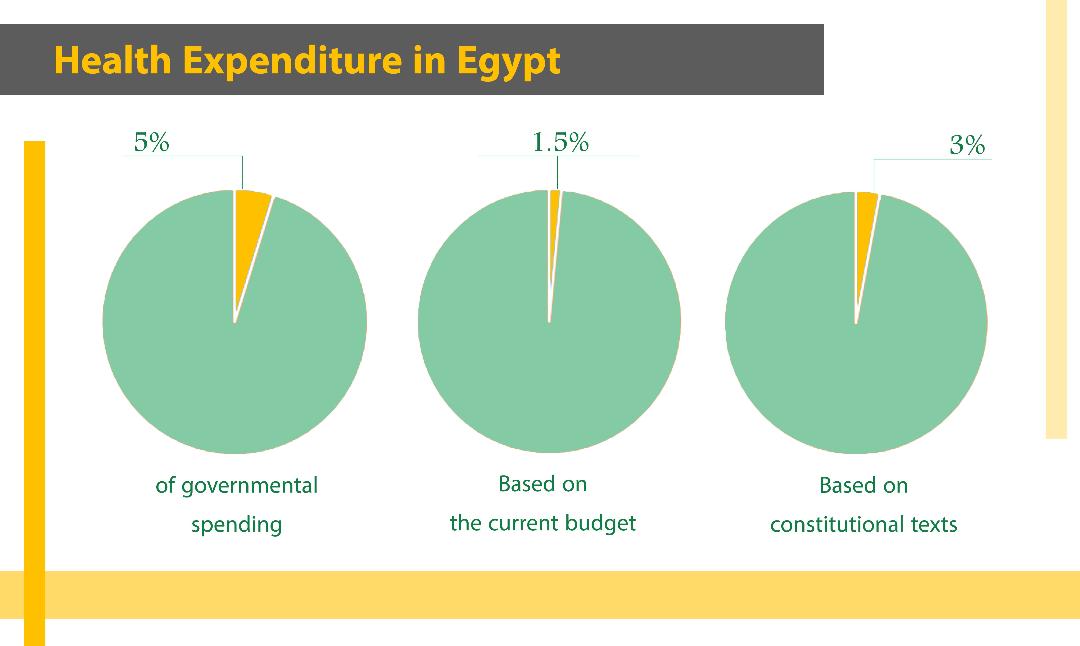

Then we have insignificant financial allocations, which never exceed the 1.5 percent of GDP, equalling 93 billion Egyptian pounds. The Egyptian constitution, however, has already stipulated that 3 percent of its GDP must be allocated to healthcare. While there are announced plans for development, most of them fall under a title of “presidential healthcare initiatives”. Still, new complaints are continuously directed against the healthcare sector in Egypt. The latter has naturally deteriorated, its features becoming clear with the emergence of the terrifying virus. How did the response go? And what was its aftermath?

Waves and preparedness

Egypt has lived through three coronavirus waves thus far. The first hit closer to power. With the end of the first week of March 2020, the Ministry of Health announced the discovery of the first cluster of infections in a cruiser in Luxor, and that the number of infections had reached 45. The numbers quickly multiplied, and, with them, Egypt transitioned from the first stage of the response (a stage of imported infection from abroad) to the stage of local infection – where it could be traced to the source. Although the number of clusters increased, tracking groups were active – in charge of visiting infected areas and tracing back the sequence of viral spread, while running the necessary tests. Naturally, however, with governmental delay in announcing a necessary pack of preventive measures, like border closure and curfew, the average number of cases transitioned into the third stage – social infection, where the source of infection cannot be determined.

In early April 2020, the number of cases in Egypt came close to 1000 infections and 66 deaths. The Ministry of Health announced then its response plan by rehabilitating 9 hospitals as quarantine centres, comprising 407 ICU beds, 346 ventilators, out of 30 hospitals that would later be incorporated into the plan. Nutrition hospitals and breast cancer centres, 46, were adopted as hospitals for triage and referral; while the rest of the hospitals were emptied out of Covid-19, to provide regular medical services.

However, very quickly, problems emerged. Reaching a quarantine hospital was rendered a challenge, as a number of perilous steps had to first be taken prior to getting there. Scenes of overcrowded hospitals multiplied beyond the quarantine map, which led, to a degree, to a kind of chaos.

For example, the National Cancer Institute announced its temporary closure, after discovering 15 infections among the medical staff there. This came after a week of a widely shared video on social media, showing institute nurses and patients’ families complaining of many suspected infections within the institute, as the management refused to run the necessary tests on workers. A few days were enough for things to get out of hand, which forced the management to announce closure and ask all visitors to head to test centres in designated hospitals in case any symptoms were showing.

Accordingly, a temporary closure was announced in a number of hospitals and central healthcare institutes, indefinitely deferring surgical operations.

On the first day of May 2020, 495 new cases were recorded, bringing the overall number of infections to 8,476 and 549 deaths. The number of quarantine hospitals reached 21, in an attempt handle the unavailability of ICU beds, especially when testing was not possible of patients, and whose infection was not categorised as “coronavirus”.

Very quickly, problems emerged. Reaching a quarantine hospital was rendered a challenge, as a number of perilous steps had to first be taken prior to getting there. Scenes of overcrowded hospitals multiplied beyond the quaratine map, which led, to a degree, to a kind of chaos.

A ministerial hotline was provided to receive citizen complaints and triage demands or quarantine referrals. With the first wave peaking, (4) however, the role of the hotline slowed down and was limited to taking note of complaints. In many cases, however, death was quicker to action than solutions (with more than 48 hours of waiting on average).

Egypt’s hospital map has generally suffered a sharp decline in recent years. The numbers of hepatitis hospitals dropped from 100 to 32, and the number of governmental hospitals dropped from 1,179 to 681 in ten years’ time – from 2007 to 2018. The number of private hospitals that same year reached 1,157 – having been 686 in 2008. The governmental share of hospital beds has also dropped in recent years, from 95 thousand and 683 beds to 35 thousand and 320 beds, of which ICU beds make up 5.8 percent with nearly 6 thousand beds and 4,500 ventilators. This means one bed per ten thousand capita, while international estimates indicate that one bed is needed for every 6 thousand citizens.

The private sector digs deeper

Responding to an aggravating situation and increased numbers calling for urgent healthcare services, the private sector entered. Except that it brought along its opportunism and profiteering which, to be precise, do not conform with Article 18 of the constitution, which considers all Egyptians equal in their right to treatment.

In a period no longer than a month, treatment stock prices ranged from 10 thousand to 50 thousand Egyptian pounds per night in an ICU bed, which caused a state of extensive popular anger. In response, the Prime Minister passed a resolution that issued a price list: the cost of spending a day in an internal isolation room is 1,500-3,000 Egyptian pounds. It determined ICU costs at 7,500-10,000 Egyptian pounds, and the cost of a ventilator usage per day around 350-650 dollars a day. Despite the cost increase for Egyptians in comparison with their incomes, whereby the poverty rate stands for 32.5 percent of the population, most hospitals did not comply with the tariff list and imposed their own prices under the pressure of demand.

The most miserable cluster of this third wave was in Sohag province, where things have gotten completely out of control since early April 2021. The number of cases exceeded 150 a day. There, cameras captured families as they recounted stories of their suffering, seeing that no empty spots were available in the central hospital.

According to official reports, 17 companies that work in healthcare and pharmaceuticals are registered in the Egyptian stock market, 16 of which comprise non-Egyptian contributors. While noting that Gulf company control over around 35 percent of the private health sector in Egypt has been growing.

Remission and renewal

The first wave began to recede with early July, whereby the Minister of Health shared the state of quarantine hospitals: “The wave has waned at a high percentage. Occupancy rates are no higher than 60 percent”.

A quiet that lasted less than three months, after which the country re-entered the turmoil. In mid-September 2020, the number of cases reached 10 thousand and 200, and deaths reached 10 thousand. With the end of 2020, the Ministry of Health announced that the number of sorting and isolation hospitals that joined the coronavirus response had reached 320 hospitals. Elevated stress was maintained as the search for empty beds continued with the beginning of the third wave in March 2021, categorised as the most aggressive, still ongoing.

Painful scenes of sorrow followed anew in succession, including the death of 5 ICU patients in a rural central hospital because, as family members proved by directly filming their relatives, oxygen stocks had run out, where a nurse in charge broke down for feeling powerless.

Medical personnel suffered – and still do – from a situation that may well be among the worst worldwide. Lacking protective gear, extensive working hours, stressful working conditions, and a useless bureaucracy that has denied mothers and carers from taking vacations, and championed risky conditions to be fulfilled before one could obtain the right to an antigenic test to screen, calculate, and record infections… All this amidst security pursuits and fired objectors.

The most miserable cluster of this third wave was in Sohag province, where things have gotten completely out of control since early April 2021, when the number of cases exceeded 150 a day. There, cameras captured families as they recounted stories of their suffering, seeing that no empty spots were available in the central hospital.

The testing business

On the other hand, as the virus spread during the first few months, severe shortage of screening tests was maintained in policy, as were the tough conditions to obtaining them. This was a major demand, especially for medical staff, where a large number of doctors and union members considered that shortage to be a direct cause of the increased numbers. Pressure campaigns were thus formed around demanding transparency and a proper management of the health file.

Thus, once the number of cases reached 28 thousand towards the end of the first wave, the number of available spots did not exceed 135 thousand – a ratio of 879 spots per million capita. In the meantime, international probes indicated that, during the first few months of the pandemic outbreak, no less than 1 percent of the population was infected, which reached 10 percent later into the pandemic. (5)

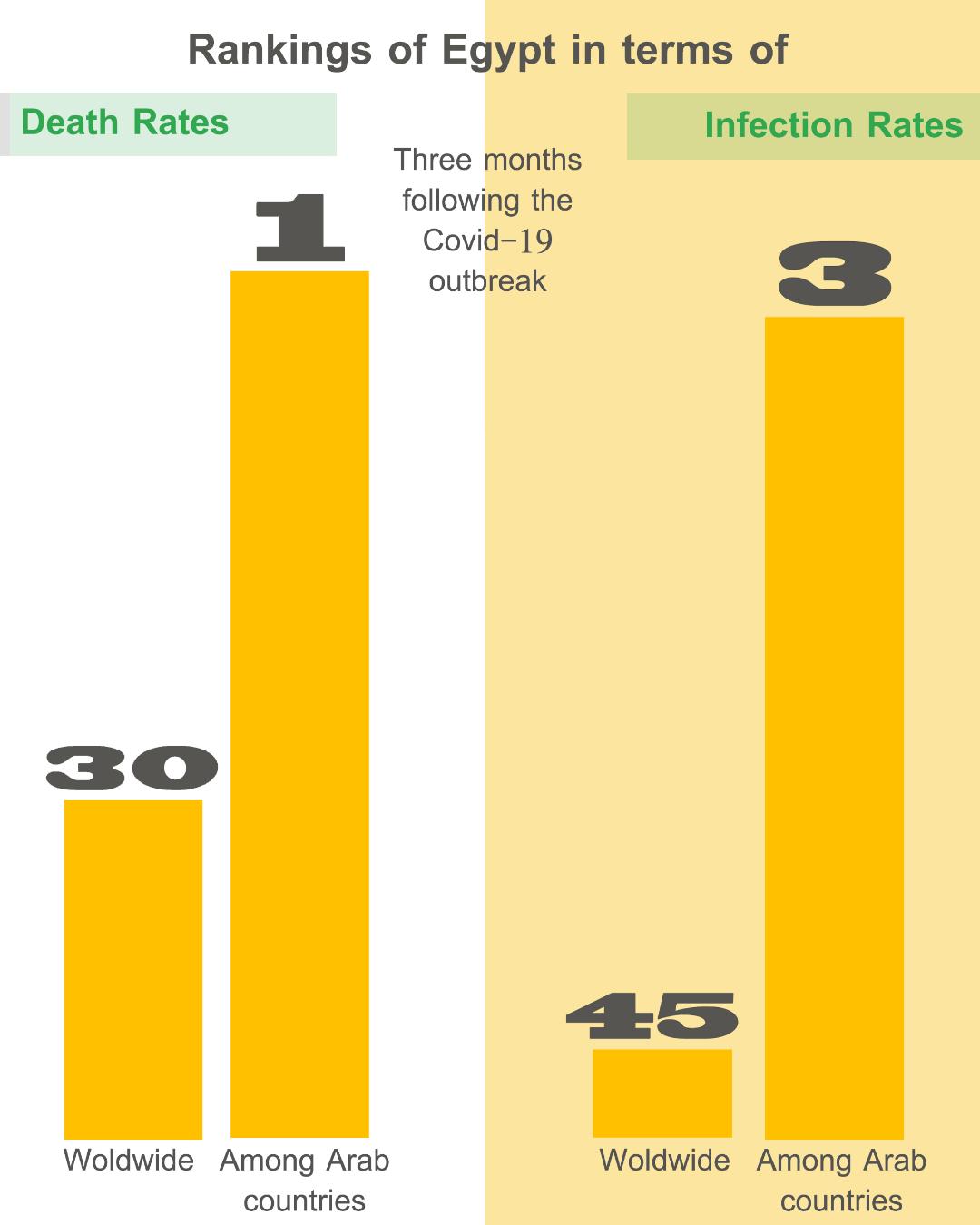

This very feeble rate and the acceleration of elevated infection rates within the country were thus interlinked, eventually taking over Egypt in three months. International ranking was 45 on an infection level, and 30 in terms of death rates. In terms of testing per million capita, Egypt ranked 141st internationally. Among Arab countries, it came in third in terms of officially announced infections, right after Saudi Arabia and Qatar. There, it came in first in terms of death rates, at a 5.9 percent as death rate, much farther away from the two aforementioned countries, which never exceeded 0.06 percent.

The Egyptian government struck three deals, two of which were with the Chinese government and one with a British government. Accordingly, it received 380 thousand PCR tests, which increased throughout the year into one million and 260 thousand tests – at 74 thousand tests per one million citizens.

Medical staff suffering

As waves extended, medical personnel suffered – and still do – from a situation that may well be among the worst worldwide. Lacking protective gear, extensive working hours, stressful working conditions, and a useless bureaucracy that has denied mothers and carers from taking vacations, and championed risky conditions to be fulfilled before one could obtain the right to an antigenic test to screen, calculate, record infections, and issue Covid-19 infection certificates. All this amidst security pursuits and fired objectors. (6)

The rates of “Duty Martyrs” increased among medical cadres, whereby the number of dead doctors exceeded 530 physicians until now (based on statistics carried out by the Doctors Union), while the Minister of Health insisted on a determined number: 130 doctors – those who worked in quarantine hospitals. The number of nurse martyrs exceeded 200, while tens of medical factory technicians, workers, administrators, and paramedics also ended up as duty martyrs.

The Doctors Union is currently fighting to obtain rights for “Doctor Martyrs” households, insure practitioners, and recommend that they abstain from work should protective gear be unavailable to them. That is in addition to the catastrophic file of coronavirus prisoners. Three doctors were arrested and accused of critiquing the system. The head of the Doctors Union, Oussama Abdel Hai said that Doctor Martyrs make up 6 percent of the coronavirus death rates in Egypt. Such is the recurring disaster that the medical cadres in Egypt have been living; it reveals the reality they have suffered all throughout the years, prior to the pandemic.

Shadi Habash is dead, let’s talk for those who remain

03-05-2020

The Murder Factories of Egypt

20-11-2015

According to the Egyptian General Doctors Union, the overall number of officially registered doctors in Egypt is around 244 thousand doctors, with nearly 188 thousand working in public and university sector hospitals, more than 30 thousand in the private sector, and nearly 35 thousand who had migrated abroad. Practically, and according to the same source, this means that for every one thousand citizens in Egypt, there are 2.1 doctors available. The Ministry of Health announced that Egypt understaffing reached more than 50 thousand doctors, a number that’s sincreasing by the year. Based on official estimates, there are around 217 thousand and 105 nurses registered in the Nurses Committee.

In general, medical staff issues have been exacerbated due to a weakened budget. A doctor’s entry level salary in a governmental hospital, who worked right after graduation, starts at 2,200 (120 dollars), but, even upon approaching retirement, would be no more than 7 thousand Egyptian pounds (500 dollars). Likewise, nursing wages in the public sector begin with 1,200 Egyptian pounds (around 65 dollars) and end up with 5,500 Egyptian pounds (around 320 dollars).

As regards healthcare technicians, according to union estimates, the number of their workers in Egypt has reached 8 thousand, while nearly double this number was recorded abroad. Most of them work two or three shifts, divided between the public hospital to which they are officially commissioned (with an entry level salary that rises no more than 1,200 Egyptian pounds, and goes nowhere beyond 3,000 even upon approaching retirement) and private hospitals.

The expenditure crisis and the spectre of endeavours

All the aforementioned reacts, even clashes, with one expression: “underspending”. In a speech he gave before the parliament in early 2021, the Egyptian Minister of Health said that the state, in addition to the annual budget, estimated at 93 billion Egyptian pounds, has provided extra financial support to the healthcare sector in response to Covid-19 – valued at 4 billion Egyptian pounds.

This prompted attentive followers to recall what the president of the republic had announced at the beginning of the outbreak in March 2020 – that he would allocate 100 billion Egyptian pounds to respond to Covid-19. How, then, does such a meagre amount end up given to healthcare, while 20 billion Egyptian pounds were redirected to support the tourism sector? Likewise, this would be compared with a previous presidential announcement, on a different occasion, of allocating 800 billion Egyptian pounds, charged to the Egyptian government, in order to develop the sector of roads and bridges in Egypt in the last five years.

The Doctors Union is currently fighting to obtain rights for “Doctor Martyrs” households, insure practitioners, and recommend that they abstain from work should protective gear be unavailable to them. That is in addition to file of coronavirus prisoners. Three doctors were arrested and accused of critiquing the system.

According to the Egyptian General Doctors Union, the overall number of officially registered doctors in Egypt is around 244 thousand doctors, with nearly 188 thousand working in public and university sector hospitals, more than 30 thousand in the private sector, and nearly 35 thousand who had migrated abroad.

As opposed to that picture, the authorities made sure to maintain efforts of what they called “presidential initiatives”: extensive activities in the domain of fighting liver diseases, early diagnosis of chronic diseases, and women and children’s healthcare. Most of these are, in fact, financed, however, by direct funds from some international institutions, and advertised as such. Furthermore, in 2017, the Egyptian parliament passed the universal healthcare insurance law, as a form of participatory healthcare that aims at developing the sector. However, up until now, only the first part of that first stage was executed – in Suez Canal cities.

**

These are the intermittent problems of the healthcare sector in Egypt, which the pandemic has come to expose in full. Spending remains the key word here. The Egyptian state has failed to figure out the right formula. Famous novelist and doctor Yusuf Idris said in his novel, written in 1957, at the dawn of the launch of the healthcare coverage plan: “Our problem with disease, gentlemen, is that of impoverishment, with the Ministry of Health being most impoverished. To resolve it is to build hospitals and encourage more medical graduates.” A saying that still rings true, and has yet to expire.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 25/05/2021

1)Almost every day, the Egyptian Ministry of Health publishes on its Facebook page a statistical graph that comprises the number of new cases, deaths, and recoveries.

2)The National Cancer Institute in Cairo is one of the most important medical institutes all over Egypt, with 7 thousand patients who frequent it, hailing from all over Egypt’s provinces when seeking treatment.

3)The Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics issues a census report every two years, and always includes an update on the number of patients, hospitals, and available medical equipment in the country, but the space dedicated to such information has been shrinking by the year.

4)On June 19th, 2020, the Ministry of Health announced the highest number of recorded cases in a day, which is 1,774, thus bringing the overall number of infections to 52 thousand and 100, and more than 2,100 deaths, 18 of whom younger than 60.

5)The website, worldometer, is an extended Google service that works by updating epidemic infection rates on a daily basis. Up till now, an international number of deaths has been recorded – and which exceeds 3 million thus far.

6)During the past fifteen years, the Egyptian Doctors Union has been through a number of successful professional strikes, the last of which is 2014, in order to improve salaries and empower and protect doctors within their work spaces.