This publication has benefited from the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. This text may be reproduced in part or in full, provided the source is acknowledged.

Covering the coronavirus pandemic in Syria conjures up the exceptional situation that distinguishes this country. This is a land dispersed into different warring authorities and powers (the Syrian government in regime-controlled areas, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the provisional government in Turkey-controlled areas in Syria, and the Syrian Salvation Government in Idlib [considered the civil wing of the Organisation for the Liberation of the Levant]). This is a land in an ongoing war, undergoing bombardments and battles, and has lost every sense of safety and services across its regions.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) only works in areas controlled by the Syrian regime. Most of its direct efforts in medical aid were carried out there, but were inaccessible to Syria’s northeast and northwest. Gaps in pandemic response efforts thus exacerbated, as did the capacity and quality of the healthcare system, alongside a number of other factors.

We hereby draw as comprehensive a panoramic picture as possible of the interplay between the coronavirus pandemic and the healthcare structures in their different shapes and kinds within Syria, along with the equipment and campaigns provided across its main regions.

A glaring contrast of numbers

Until mid-April 2021, the statistics published on the Ministry of Health website show 21,004 confirmed coronavirus cases and 1,473 deaths in government-controlled areas. These numbers, however, are in question by both local and international actors. For instance, on September 15th, 2020, Imperial College London published a study in which it states that governmental reports counted no more than 1.25 percent of actual deaths from the coronavirus in Damascus. The study reveals that, in the period between September 2nd to 15th, there were 4,380 coronavirus deaths in the city that failed to be officially recorded, adding that those cases managed to get reported thanks to elevated surveillance measures in Damascus, thus inferring that death rates beyond the capital could indeed be much higher – as medical activists and actors were unable to monitor them.

Syria in Context website has estimated that Damascus alone had at least 85 thousand coronavirus cases. In so doing, it based its conclusions on obituary pages published online from July 29th until August 1st 2021, along with satellite pictures of cemeteries, interviews with doctors, and otherwise.

As the Syrian regime relies on a strategy that targeted hospitals in its war on the opposition, even during the outbreak of Covid-19, 49 percent of respondents expressed fear of seeking medical help, for fear of attacks. Remaining medical practitioners risk their lives by continuing to provide medical care under ongoing violence and shortage of medication and equipment.

In May 2020, the Syrian president justified looser restrictions by saying that citizens now faced a choice between “impoverished hunger and illness”, and that “impoverishment-induced hunger was a certain, rather than probable, case, whereas illness was no more than a probability. The result of hunger is already determined, while the results of infection are undetermined”.

The latest estimates, published on April 16th, 2021, are derived from the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), which states that infections within regime-controlled areas have reached 859,600 confirmed cases, of which 545 thousand are recoveries and 22,645 are deaths.

Official medical sources in Damascus had already confirmed the outbreak of a third wave of the virus since March 2021, followed by a statement issued by the director of Al-Mujtahid Hospital in Damascus on March 20th, 2021 to the effect that the regime-controlled areas have reached their epidemic peak, and that this wave was “tougher than its predecessors”.

In northwest Syria, the numbers issued by the Early Warning Alert and Response Network on April 16th, 2021 show a rise in the number of registered cases: 21,623, which comprise 19,661 recoveries and 638 deaths. Susan Khush, director of the response efforts for Syria of Save the Children organisation, had warned at the beginning of the year that the “situation was much worse than numbers revealed”, which the organisation ascribes to insufficient testing and shortage of medical supplies.

Such a warning echoes the words that the healthcare director of Idlib said to the Middle East Eye website in December 2020, noting that the number of Covid-19 deaths could be much higher in northwest Syria because home-deaths were not officially recorded as physicians could not determine whether those were incurred by Covid-19 or otherwise.

In early April this year, the Northern Syria Response Coordinators cautioned against the significant rise in coronavirus cases, followed by the Syrian Civil Defense which warned against a new pandemic wave, “possibly graver than its predecessors”.

Similarly, residents of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria have been facing a most violent and fast-spreading third wave with the arrival of the new variant. The latest numbers published by the Health Board of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, and which cover the beginning of the pandemic until mid-April, note 12,756 coronavirus cases, of which 432 were concluded in death and 1,382 in recovery. A series of new protective measures was thus introduced, be it through imposing curfews or banning assemblies. The reality of pandemic spread in these areas might also differ from the issued numbers, due to insufficient lab tests, a weakened medical infrastructure, and lack of transparency.

An aftermath of war

Ten years of conflict have left destructive marks on healthcare and life systems in Syria. Repeated warning calls would caution against declining hospital capacities and underequipped healthcare systems in the different regions of the country – even before the coronavirus spread. In March 2021, the UNCHR described the situation of healthcare in Syria as “catastrophic”, where only 58 percent of hospitals were fully functional and only 53 percent of medical centres that provided basic services were fully functional. In a report issued by the International Rescue Committee (IRC) on March 3rd, 2021, titled “A decade of attacks on health care in Syria”, the committee documented an extensive and substantial effect on healthcare facilities and healthcare workers. The report noted that 81 percent of surveyed healthcare workers knew a colleague or a patient who was wounded or murdered due to an attack, at least 77 percent had witnessed an average of four attacks on healthcare facilities, while some had witnessed up to 20 attacks throughout the years of war (raids constituted 72 percent of attacks), while 56 percent expressed fears of living near a healthcare facility – lest they be attacked.

Although the healthcare facilities are protected by international law, the report concludes that the “healthcare system is devastated in Syria, and that opposition-controlled areas suffered the biggest damage”.

In March 2020, WHO registered 494 attacks against medical facilities in Syria, of which 337 occurred in northwest Syria – between 2016 and 2019, and noted that only half those 550 medical facilities remained functional.

As the Syrian regime relied on a strategy that targeted hospitals in its war on the opposition, even during the outbreak of Covid-19, 49 percent of respondents expressed fear of seeking medical help, for fear of attacks. Remaining medical practitioners risked their lives by continuing to provide medical care under ongoing violence and shortage of medication and equipment. Notably, some hospitals were set up in cellars or underground shelters for protection. The report also notes that around 70 percent of healthcare workers has left the country, bringing the ratio down to one doctor per ten thousand Syrians. Healthcare workers are therefore forced to work more than 80 hours a week to counteract understaffing. In March 2020, Doctors Without Borders considered that the healthcare system in Syria was indeed on the verge of collapse, with supplies and medical cadres hitting a low point.

Damascus and regime-controlled areas

On March 22nd, 2020, the Syrian minister of health announced the first confirmed coronavirus case in the country, but only after weeks of rumours, announcements of all neighbouring countries that the pandemic had hit their lands, and the emergence of a number of indications suggesting the regime was trying to hide the reality on the ground.

Ever since the announcement of the first case, many facets of the Syrian authorities’ response to the pandemic have been shrouded in mystery and confusion. Medical staff were at the frontlines of responding to the virus, but Human Rights Watch (HRW) accused the regime of failure to provide adequate protection to workers. One such prominent moment took place when the Union of Syrian Doctors announced 61 deaths among doctors and healthcare workers in August 2020, when the advertised official number of overall deaths in the country was only 64.

According to a statement by HRW doctors, deaths announced on official government pages mainly covered the elite, like hospital directors or former medical professors. Doctors then estimated, based on their own familiarity with doctors and nurses at the frontlines of the response effort, that the number of deaths among them was (most likely) much higher, as healthcare employees in rural areas could not be counted.

According to a Syrian ministry of health report on November 29th, 2020, the number of governmental and private centres and laboratories certified to carry out PCR testing reached 19 laboratories. One test cost around 100 US dollars, almost double the average wage of governmental salaries in a country with 80 percent of its population living under the poverty line – according to UN estimates.

The organisation ties “underreporting” with many factors, most significant of which are governmental restrictions on informing relief workers of test results during the early stages and lack of largescale testing, that is, despite pressure from healthcare organisations to increase testing capacities, warning that as a UN organisation, WHO cannot control reporting as it only works under governmental authorisation. In turn, in early 2021, SOHR documented the names of 172 doctors within regime-controlled areas who died of covid-19 in 2020. Furthermore, in September 2020, around 200 UN employees in Syria appeared to have contracted the virus.

Fighting against the spread of the coronavirus in regime-controlled areas has faced a number of different issues, at the top of which are an exerted healthcare system, medical understaffing, limited testing and medical resources, weakened governmental hospitals, and a general economic collapse – which has rendered people incapable of applying any of the globally adopted protective measures or meeting the very basic requirements for protection.

The director of ambulances and emergency in the ministry of health affirmed that the ministry of health is now applying an emergency plan B, and that all healthcare institutions and cadres are mobilised to the maximum extent, stating, in March 2021, that on the official Syrian Arab News Agency website (SANA) “the rate of occupied ICU beds with Covid-19 patients in public hospitals designated for confirmed and suspected coronavirus cases in Damascus has reached 100 percent,” adding that some coronavirus patients that required intensive care were transferred to other governorates, as hospitals in the capital had reached maximum capacity.

Likewise, WHO reported that, according to nurses and doctors, governmental hospitals ready to deal with Covid-19 cases have surpassed their maximum capacity, noting that no other hospitals were equipped with the required infrastructure to handle the outbreak. They ascribed it to lack of oxygen cannisters, ventilators, and beds. With the outbreak of the third wave, a number of warnings stated that the Syrian healthcare system was reaching capacity and that the pandemic was out of control. Most recent of those warnings was issued by a member of the consultingCovid-19 response team in Damascus. He stated that many of the incoming cases into al-Mouasat University Hospital resulted in deaths due to a shortage of capacities, other related governmental measures of suspended learning, and a bunch of other closures. This was in contradiction with the governmental step to loosen measures in May 2020, as the Syrian president justified it by saying that citizens now faced a choice between “impoverished hunger and illness”, and that “impoverishment-induced hunger was a certain, rather than probable, case, whereas illness was no more than a probability. The result of hunger is already determined, while the results of infection are undetermined”.

According to a Syrian ministry of health report on November 29th, 2020, the number of governmental and private centres and laboratories certified to carry out PCR testing reached 19 laboratories. One test cost around 100 US dollars, almost double the average wage of governmental salaries in a country with 80 percent of its population living under the poverty line – according to UN estimates.

With the stifling economic crisis and 11 million people in Syria in need of humanitarian aid, it becomes difficult to wear masks or receive oxygen cannisters, required medication, and ventilators when needed. In parallel, tens of cases resort to self-homecare, as hospitals receive only extremely serious cases.

The issue of prisoners in regime-controlled areas is also conjured up here. According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, 130 thousand people are still detained or forcibly disappeared, while human rights organisations had warned about the fate of detainees in Syrian central jails and prison camps should a viral outbreak take place among them – due to detention conditions, overcrowding, lack of medical services, intentional famishment, and lack of healthcare, hygiene, and preventive basics. It called on the regime to release them, but received no response.

Camps

A decade of fighting in Syria has resulted in the biggest migration crisis the world has seen since WWII. According to the United Nations, besides the 6.6 million people who migrated abroad, 6.7 million people remain internally displaced. The latter, especially those living in camps, are considered the most affected by the coronavirus pandemic, for reasons related to their living conditions, and impossibility to apply adequate protective measures to prevent, or protect from, the spread of the virus.

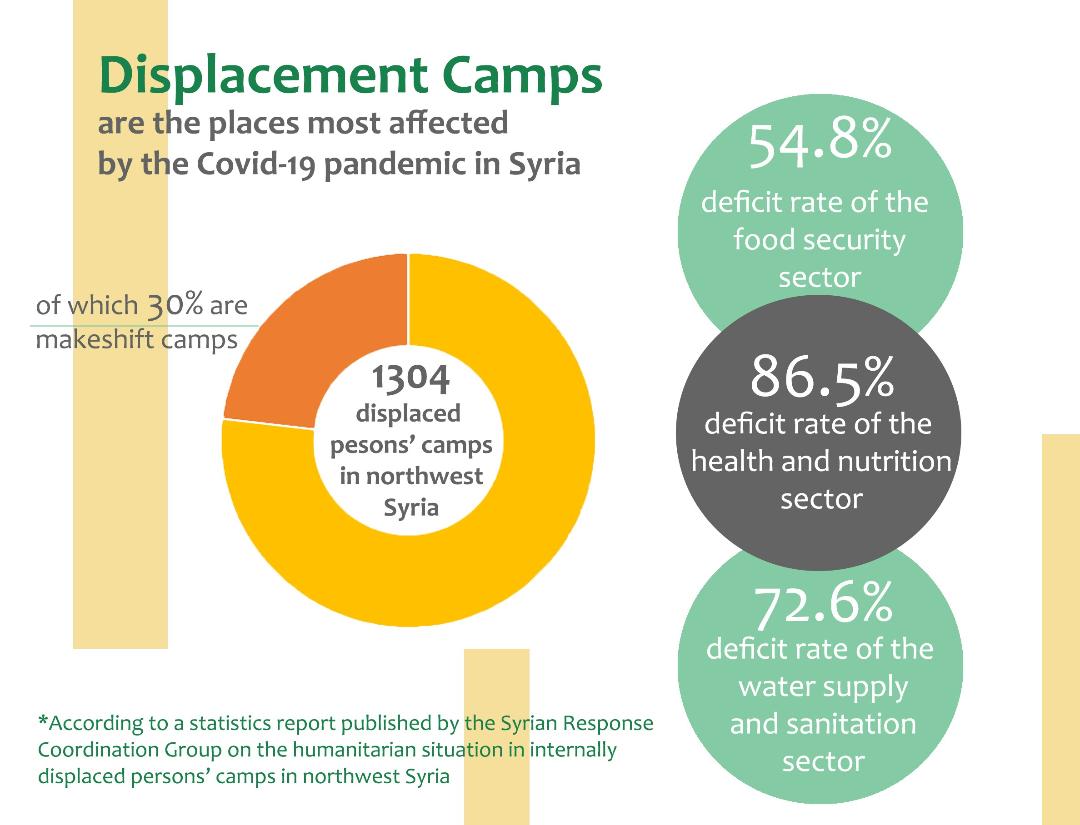

In a statistical report that the Syrian Response Coordinators issued on December 29th, 2020 (a local NGO), the team documented the humanitarian situation in displaced persons camps in northwest Syria, along with their conditions and major problems its population faces. The statistics revealed that the total number of camps was 1,304, in which one million and 48 thousand displaced persons reside, including 393 makeshift camps in which 187,764 displaced persons reside. The report notes the deficit in humanitarian response which, according to the team, has reached 54.8 percent in the food security and livelihood sector, 72.6 percent in the water and sanitation sector, reached 86.5 percent in the health and nutrition sector, 74.9 percent in the protection sector, and 54.4 percent in the shelter sector – which is the percentage linked with securing tents for makeshift camps. The percentage of deficit is notably higher in all sectors when compared with the same report from the same organisation in August 2020.

According to the organisation, healthcare is among the most prominent problematic facets that displaced persons face in camps; unhygienic environment, pollution hazards, especially in makeshift camps, the spread of exposed sewage pits, deprivation of main income sources while relying on humanitarian aid only, lack of healthcare and preventive essentials needed against the novel coronavirus. The report mentions the need for ensuring a stable and uninterrupted healthcare system in the camps, as the increase in the number of coronavirus cases among displaced persons and the management of Covid-19 patient operations were two among the most prominent challenges that camps faced in northwest Syria.

Generally speaking, as overcrowding in northern camps increases along with pressure on their capacity to receive displaced persons, makeshift camps are formed with every new wave of displacement. Residents of those makeshift camps could be forced to spend months out in the open with no access to any healthcare facilities whatsoever.

Many camp residents have expressed powerlessness to protect themselves from a Covid-19 infection. Self-isolation is difficult to achieve as is social distancing in these overcrowded camps. Even the bare minimum of preventive basics is lacking, while regularly washing hands is considered an unrealistic option, as many camp residents rely on shared water reservoirs.

According to Doctors Without Borders, clean water is hardly available in some camps, with some resorting to shared bathrooms. An Assistance Coordination Unit report issued in December 2020 shows lack of public bathrooms in 65 percent of the camps included in the study, and that only 55 percent of camps that include bathrooms have regular water supply. People cannot be asked to “stay home” at a time when more than a third of Idlib’s population have been expelled from their homes and densely assembled in unliveable camps, the majority of which lack basic services. Additionally, Doctors Without Borders has noted at the beginning of the pandemic that 35 percent of its patients already suffered breathing difficulties, which further complicates matters in case they contracted the virus.

The total number of camps within Syria is 1,304, in which one million and 48 thousand displaced persons reside, including 393 makeshift camps in which 187,764 displaced persons reside. The deficit in humanitarian response which, has reached 54.8 percent in the food security and livelihood sector, 72.6 percent in the water and sanitation sector, and 86.5 percent in the health and nutrition sector.

In parallel, through the fifteen reports it published, the Center for Civil Society and Democracy periodically monitored recent developments in the Covid-19 pandemic and related measures in Syria from March 19th, 2020 until September 30th, 2020. They repeatedly mention a decline in awareness of the gravity of the virus and level of popular cooperation with civil society organisations. Those reports document several cases in which a Covid-19 carrier mingled with others without wearing a mask, only for others to later find out about it. One such example was noted in waiting rooms overcrowded with inspectors in Al-Ikhaa Hospital – despite flu symptoms showing on some people in the waiting room, who wore no masks. Similarly, people overcrowded markets and even registration counters in medical centres and maternal and childcare centres in some camps.

Reports note a link between impoverishment and lack of a bare minimum of purchasing power to access sanitisers and protective masks, reiterated by Doctors Without Borders – which noted some attempts to create alternative solutions, with some teachers instructing their learners to use old pieces of cloth to cover their faces, while others resorted to covering their faces with their sleeves when mingling with others was inevitable.

What further complicates things is the repeated exposure of camps to successive rainfalls, which brought the Syrian Response Coordinators to announce on January 31st, 2021 that “all camps in Idlib Governorate and its rural areas as well as rural Aleppo were completely devastated”. Such climate conditions caused the destruction of hundreds of tents and damages to thousands of others, while many families remained in the open or were forced to find refuge in their relatives’ tents – which essentially produces an environment of impossible social distancing or any other basic preventive measure.

Healthcare in northwest Syria

The healthcare system in northwest Syria, controlled by Syrian opposition factions, faces major challenges in dealing with the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, especially with no internationally recognised government, which complicates the arrival of aid. Generally speaking, people in these areas rely on NGOs to receive healthcare and other humanitarian programmes and basic services.

According to Doctors Without Borders in an update issued on November 12th, 2020, only nine hospitals were designated to treat Covid-19, serving a population of almost four million people, in addition to 36 isolation and treatment centres that provided basic care to patients with light symptoms, 3 laboratories for testing, with frequently less than 1,000 daily tests.

According to the Idlib health board, there are only 600 doctors in northern Syria – that is, 1.4 doctors per one thousand inhabitants – which is less than the bare minimum required in crises – normally counting five doctors per ten thousand inhabitants. We bear in mind that Doctors Without Borders said back in September 2020: that around 30 percent of infections in northwest Syria were recorded among healthcare workers.

Additionally, in a video published in March 2020, the director of the Idlib health board spoke about 201 ICU beds back then, which means less than one ICU bed per 20 thousand inhabitants, 95 ventilators for adults only, with a 100 percent occupancy rate at the time (including other diseases).

Revisiting the statistics mentioned in the central healthcare database issued by the provisional Syrian government on April 15th, 2021, one notes three active laboratories for coronavirus testing, which carried out more than 4,000 tests during the last week the report covered. Those results showed a ratio of confirmed cases that reached 3.78 percent of the overall screenings carried out that week. According to that same report, there are 25 active social isolation centres, containing a number of beds that reached 1,158, 9 hospitals for isolation and treatment, containing only 340 beds, 142 ICU beds, and 131 functional automatic ventilators.

Only nine hospitals were designated to treat Covid-19 in northwest Syria, serving a population of almost four million people, in addition to 36 isolation and treatment centres that provide basic care to patients with light symptoms, 3 laboratories for testing, with frequently less than 1,000 daily tests. Only 600 doctors serve northern Syria.

In a statement issued by the Turkish Shanliurfa Province issued in early January 2021, the province announced that it established five laboratories designated for Covid-19 PCR testing in the cities of Tal Abyad and Ras el Ayn, both located within the Turkey-controlled areas in northern Syria, and that those laboratories would provide test results requested by those who wished to pass through Turkish-Syrian border crossings.

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

Similar to areas west to them, areas in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria suffer severe lack in materials and a spread of the virus all throughout its region. Reports mention shortages of medical equipment and supplies and understaffing in most hospitals located within Kurdish-controlled areas.

On April 12th, 2021, Juwan Mustafa, co-chair of the Health Board of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria stated that “the region has moved into a very dangerous stage” because of the coronavirus, and that the board was “on the verge of losing all control over this virus. To prevent its spread, the board has imposed a full lockdown all across northern and eastern Syria. In a press conference, he stressed that the Health Board was “incapable of stopping the spread” and that “all quarantine centres prepared to receive affected cases are now completely full”. The Health Board of the Autonomous Administration had prepared 13 quarantine centres to treat suspected coronavirus cases in the early months of the pandemic outbreak, calling on the UN for help, as many areas lacked hospitals or PCR testing equipment in their laboratories. They also lack ventilators and x-ray machines, while they have access to no more than 27 ICUs and x-ray machines all over the Autonomous Administration areas, at a time when the population count has outnumbered five million people.

Similar to areas west to them, areas in the Autonomous Administration suffer severe lack in materials and a spread of the virus all throughout its region. Reports mention shortages of medical equipment and supplies and understaffing in most hospitals located in areas under Kurdish militias control.

Despite those calls, WHO response remained shackled by the restrictions imposed upon it by the Syrian regime, which does not cooperate with the Autonomous Administration in its efforts to respond to the virus. Areas under the Autonomous Administration now have PCR testing labs to screen for the virus, but those were offered as aid by the Iraqi Kurdistan and the Kurdish Red Crescent, and do not suffice.

HRW documented that the authorities in Damascus have refused to collect samples from northeast Syria to screen them for coronavirus infections. Areas under the Autonomous Administration suffer from restrictions imposed on aid delivered from Damascus and Iraq, which obstruct the arrival of supplies and medical staff needed to ward off and handle the outbreak.

***

As such, all across the Syrian territories, in all their classifications and conditions, the coronavirus reveals the tragic sight to which the country has arrived, along with an outbreak getting out of control, as the entire Syrian people, in cities and rural areas alike, fall prey to disease, war, and destruction.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of Assafir Al-Arabi and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation cannot accept any liability for it.

Translated from Arabic by Yasmine Haj

Published in Assafir Al-Arabi on 24/04/2021